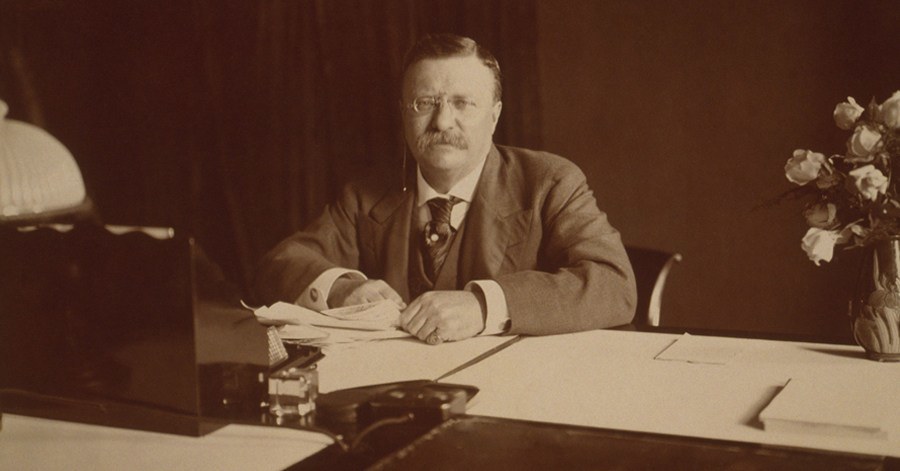

Roosevelt was a serious writer and one of America’s great readers — in addition to being the 26th president of the United States, the Governor of New York, Police Commissioner of New York, a U.S. Civil Service Commissioner, and the hero of San Juan Hill.

We all know how much Theodore Roosevelt wrote — somewhere between 35 and 40 books, depending on how you count, 155,000 letters, innumerable op-ed pieces, articles, and newspaper columns. He did all of this while also pursuing a breakneck life of adventure and strenuosity — hunting on four continents, giving a zillion stump speeches on his many journeys through America, leading friends and family on his punishing point-to-point hikes, and rowing in the bay with his wife Edith, not to mention climbing the Matterhorn on his honeymoon.

Theodore Roosevelt was a serious writer and intellectual and one of America’s great readers — in addition to being the 26th president of the United States, the Governor of New York, Police Commissioner of New York, a U.S. Civil Service Commissioner, and the hero of San Juan Hill.

How he did all of this — almost entirely without the help of ghost writers — is hard to figure. When did he sleep?

Take the letters alone. Roosevelt lived 60 years — 155,000 letters comes to more than 2,500 per year. Surely the great bulk of those were dictated to secretaries, including William Loeb, while TR served as president of the United States. Even, so that’s 6.8 letters per day, year in and year out. Many of the letters can be characterized as notes: thanks for the rifle; Edith and I hope you’ll come to Sagamore on Thursday. But the great bulk of his correspondence is rich in length and detail. When he returned from his 1903 presidential romp around America, he wrote his Secretary of State John Hay a letter of 36 typewritten pages, recounting his 14,000-mile journey, full of real and often exaggerated tales of his time on the Dakota frontier back in the 1880s.

But what is most impressive is how well he wrote. Several passages in his three books about his experiences in the badlands of Dakota Territory, the great chapter “In Cowboy Land” in his 1913 Autobiography, and many letters written in and about his Dakota experiences, represent the best that has ever been written on the subject. And the hard thinking behind the muscular and straightforward prose was prescient. He understood that open range ranching represented an ephemeral stage in the development of the western plains, soon to be displaced by homesteaders. He recognized that the cattle barons were overgrazing the commons and that some form of regulation — preferably local grazing associations — would be necessary to sustain the grasslands. He realized that the once-infinite buffalo herds of the West were incompatible with any significant level of white settlement. And he wrote about all of that in clear, forceful, often magical prose.

I remember hearing Roosevelt’s great biographer Edmund Morris speaking in 2007 at the dedication of the U.S. Forest Service’s acquisition of the east range of the Elkhorn Ranch north of Medora. In the Burning Hills Amphitheater on a hot summer day, the elegant Kenya-born Morris, looking up at the crowd through his half-glasses, read the opening passage from “In Cowboy Land,” in which Roosevelt wrote, “It was still the Wild West in those days, the Far West, the West of Owen Wister’s stories and Frederic Remington’s drawings, the West of the Indian and the buffalo-hunter, the soldier and the cow-puncher. … It was a land of vast silent spaces, of lonely rivers, and of plains where the wild game stared at the passing horseman.”

After beautifully reading the passage in his impeccable British colonial accent, Morris looked up and said, “I wonder if you Yanks will ever have another president who can write like this.” A murmur swept through the audience, not sure whether to be offended or to applaud the undoubted truth of what Morris said.

A great president who was also a great writer. Who else? Jefferson, Lincoln, possibly JFK.

“I wonder if you Yanks will ever have another president who can write like this.”

Biographer Edmund Morris

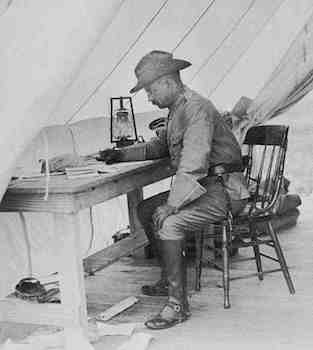

How did he write so much? The key to writing books is perseverance, doggedness, and discipline. The British curmudgeon Dr. Johnson said, “a man may write at any time, if he will set himself doggedly to it.” That was Roosevelt. He wrote his major speeches weeks before he had to deliver them. On safari and on his life-threatening exploration of the River of Doubt, he capped off days of pain and sheer exhaustion by writing up the latest adventures in triplicate with a thick pencil. Because he was not writing for literary effect, not attempting complex Ciceronian sentences, not experimenting with figurative language, not straining at purple prose, but just getting it all down on paper, he never suffered from writer’s block, never failed to meet his deadlines.

He also needed the money — at least until he became an accidental president in September 1901. Dr. Johnson also said, “No man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money.” Although TR let his friends and family know that he needed to publish books to support his lifestyle, his six children, and his beloved home at Sagamore Hill, he would probably have been a prolific author if he had been rich beyond monetary concerns. He had a lot to say. His confidence was enormous. He wanted to pull the American people into the 20th century, onto the world stage, and he knew that his words were an essential tool of his leadership, at home and abroad.

Roosevelt did not think of himself as a great writer. He told his closest friend Henry Cabot Lodge that he was essentially a journeyman — a “literary feller.” Reviewing TR’s Gouverneur Morris in 1887, The New York Times said, “Mr. Roosevelt has no style as style is understood,” but “his meaning is never to be mistaken.” Roosevelt’s prose was muscular, straightforward, and lucid. He piled sentence upon sentence until he had completed his task. What perhaps he did not recognize was that it was the unadorned simplicity and virility of his prose that makes him a great writer. He was practicing a square deal with the English language. He knew his adventures would carry the prose, not the other way around. He always regarded himself as an average man with a huge internal furnace. He would make up in discipline and exuberance what he lacked in literary talent. He believed his “averageness” gave him unique rapport with the vast bulk of the American people.

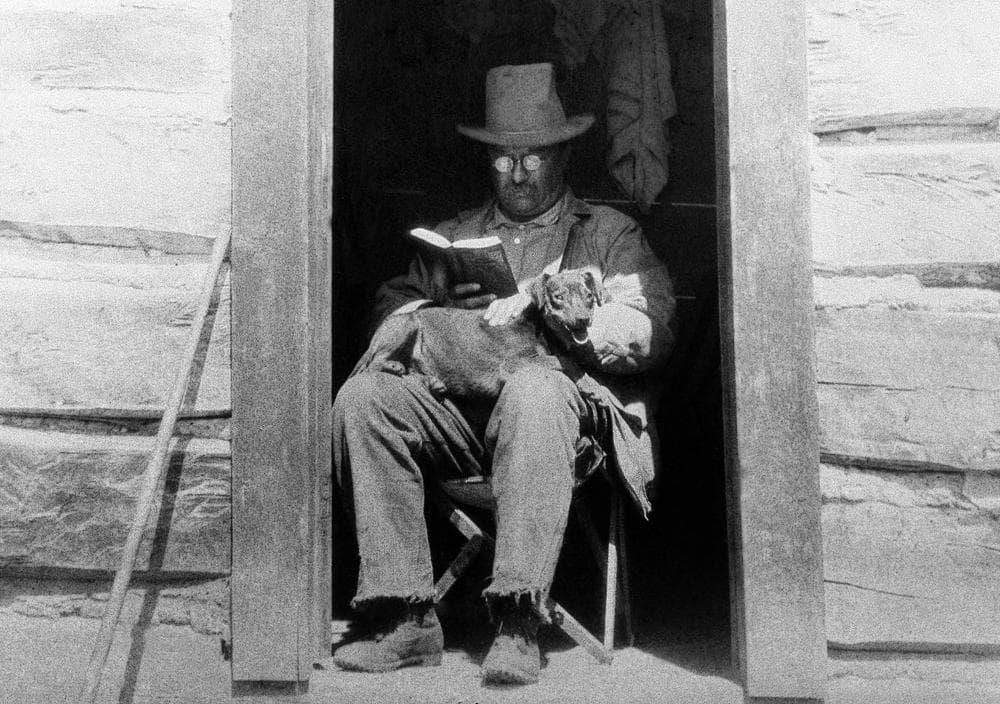

A dedicated reader could probably work through all of Roosevelt’s works in a single year. That would be worth doing, with several Excel charts open through the process. One would compile a list of every metaphor, simile, or rhetorical flourish he employed in the books and letters. It would, I believe, be a short list. Another would list the stories and arguments he repeats numerous times. A third might be a chart of his exaggerations of the number of years he spent on the Dakota frontier. Was it three, five, eight, 10, or 15 as he once claimed? (It was three.) A fourth would list all the books this most bookish of presidents referred to in his writings. Roosevelt spends more time writing about the books he is reading than any historical figure I know — more than Thomas Jefferson, America’s first great bibliophile, more than John Adams, who seems to have read more than Jefferson.

He seems to have read something like a book a day. In an astonishing letter to Nicholas Murray Butler on November 4, 1903, among other things, President Roosevelt tried to list the books he had read in the last two years. The total is staggering: scores of books, some of them multi-volume histories of faraway places, classics of Greek and Latin literature, all of the Greek historian Polybius, Herodotus, Macaulay’s essays, Hay and Nicolay’s multi-volume biography of Lincoln, a number of Shakespeare’s plays, portions of the German epic Nibelungenlied. And on and on and on. While serving as the most energetic president of the United States.

Reading all of Roosevelt would be a strenuous project illuminating the life and mind of the most strenuous of presidents. Contrary to conventional wisdom, I believe one’s respect for Roosevelt would be greatly enhanced by such a project. One essential purpose of the Theodore Roosevelt Center at Dickinson State University is to insist that Roosevelt’s greatness lies as much in his mind, his thought, his writing, his understanding of the world’s literature, and his grasp of history and world affairs, as in his many public and private adventures. He said, “Happiness … lies in the joy of achievement, in the thrill of creative effort.”

On August 24, 1884, out on the trail somewhere near the Powder River in Wyoming, TR took the time to write to his new friend Henry Cabot Lodge. Among other things, the 900-word letter discussed a veto by Grover Cleveland of New York; the many requests TR was getting to give political speeches; the strenuous joys of frontier life; his dislike of the mugwumps; critical reviews of Lodge’s latest book Studies in History; TR’s belief that Lodge was wrong to blame Cornwallis for the debacle at Yorktown; the character of George III; and his antagonism to the Republican presidential candidate James Blaine. But here’s what is chiefly interesting. Here’s the opening paragraph of the letter:

My dear Lodge, You must pardon the paper and general appearance of this letter, as I am writing out in camp, a hundred miles or so from any house; and indeed whether this letter is, or is not, ever delivered depends partly on Providence, and partly on the good will of an equally inscrutable personage, either a cowboy or a horse thief, whom we have just met, and who has volunteered to post it — my men are watching him with anything but friendly eyes, as they think he is going to try to steal our ponies.”

That’s a true man of letters. That’s the greatness of Theodore Roosevelt.