Imagine America if Theodore Roosevelt had never been president.

Theodore Roosevelt was president of the United States for seven years, 171 days. He came in through the back door when President William McKinley was assassinated in September 1901. During his “two” terms, Roosevelt set aside 230 million acres of the public domain as National Parks, National Monuments, National Forests, National Wildlife Refuges, and National Game Preserves.

It’s almost unbelievable. Roosevelt alone is responsible for creating more than 75% of all the National Forests in the United States. Roosevelt invented the National Wildlife Refuge System by Executive Order and named the first 51, beginning with Pelican Island in Florida. He named the first 18 National Monuments, including Devils Tower, Muir Woods, and the Grand Canyon.

Roosevelt could easily have won a third term if he had chosen to run in 1908, but he vowed on election day 1904 that two terms would be enough — a vow he said he regretted every day for the rest of his life! We can only imagine what he would have done with “four more years” (1909-1913).

At the annual Theodore Roosevelt humanities symposium in Dickinson, North Dakota, recently, someone who knows the contentiousness of today’s conservation agenda in the American West asked, “How did he get away with it?” I’ve been thinking about that question all weekend.

First, let us praise Theodore Roosevelt. I once asked the great Charles Wilkinson, an eminent environmental law professor at the University of Colorado at Boulder, now unfortunately deceased, whether it was possible to exaggerate Roosevelt’s conservation achievement. “Absolutely not!” he said. “Nobody did more. Nobody did better.”

“Not one cent for scenery!” — House Speaker Joe Cannon

Just try to imagine the American West if Theodore Roosevelt had never been born and had never ascended to the presidency in the wake of an anarchist’s bullet. His predecessor William McKinley’s conservation achievement was miniscule. William Howard Taft did little. Woodrow Wilson, not much. Congress was no help. After TR took the oath of office in Buffalo, New York, on September 14, 1901, and made his conservation agenda known, Speaker of the House Joe Cannon said, “Not one cent for scenery!” Accordingly, Roosevelt accomplished most of his conservation agenda through Executive Orders. Just imagine one of today’s maps of the public lands of the United States, with each of Roosevelt’s conservation properties dissolving into private ownership. There are people on the far right who want to do just that. It would be a radically diminished West, a spiritually impoverished America.

Eight Reasons TR Achieved the Near Impossible

So how did he get away with it? There are several factors, some more important than others.

1. In Roosevelt’s time, the West was sparsely populated. In 1900, approximately 11 million people (15% of the national population of 76 million) lived on the Great Plains or farther west in California. The heart of the West was very lightly populated. Today, 125 million people live in the West, which is 38% of the national population. Roosevelt’s West was comparatively empty. Most Americans couldn’t have located the Petrified Forest (Arizona), Pinnacles (California), Chaco Canyon (New Mexico), or even Devils Tower on a map. It was easier to designate far away places — many of which nobody had ever heard of — on a tabula rasa than in any densely populated area.

2. Roosevelt designated his conservation properties before the opposition could get organized and funded. Today, the fierce advocates of privatization and “no net gain” in federally protected landscapes are well organized, well funded, and ready to spring into strenuous opposition at a moment’s notice. It’s not that there was no opposition to Roosevelt’s conservation agenda, but the fact is that his passion for conservation was well ahead of his time. His breathtaking environmental achievement — a revolution in our national thinking about the public domain — crossed the finishing line before the opposition forces could get their act together.

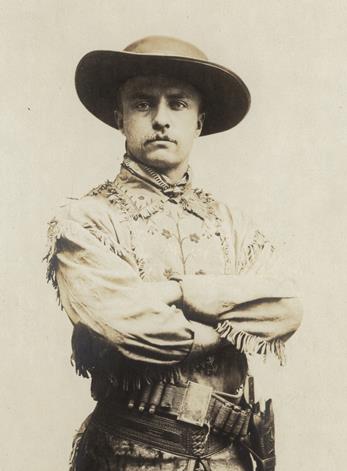

3. Roosevelt was an authentic westerner. He was born in New York, and his home was on Long Island, but he had ventured west in 1883 and re-invented himself as a cowboy, rancher, and big game hunter in the badlands of the Little Missouri River. In his 4th of July speech in tiny Dickinson, Dakota Territory, in 1886, Roosevelt said, “I am myself at heart as much a Westerner as an Easterner. I am proud indeed to be considered one of yourselves, and I address you in this rather solemn strain today only because of my pride in you and because your welfare, moral as well as material, is so near my heart.” In other words, Roosevelt had not only walked the walk but thrown himself into monthlong cattle roundups, helped stop stampedes, arrested desperadoes and brought them to justice, ridden his horse Manitou alone over some of the emptiest landscapes of America, punched out a ruffian in a saloon, killed a grizzly bear, and slept for days at a time on the ground. He was no Michael Dukakis posing for a photo op in a tank or John Kerry wearing unaccustomed camouflage while posing as an avid hunter. The American people recognized him as a man whose second home was west of the 100th meridian. That gave him credibility when he sought to lock up some extraordinary landscapes “for your children, your children’s children and for all who come after you,” as he said at the south rim of the Grand Canyon on May 6, 1903.

4. Roosevelt was a larger-than-life figure with more charisma than any person of his time, with the possible exception of Mark Twain. His ebullience and his passion were infectious. On the few occasions when he could not inspire, he could exhaust. One visitor to Roosevelt’s White House said, “You go to the White House, you shake hands with Roosevelt and hear him talk — and then you go home to wring the personality out of your clothes.” The skeptic Henry Adams said, “Roosevelt, more than any other man … showed the singular primitive quality that belongs to ultimate matter — the quality that medieval theology assigned to God — he was pure act.” It was hard to resist TR. He was even better at bending others to his will than Lyndon Johnson, another great conservation president.

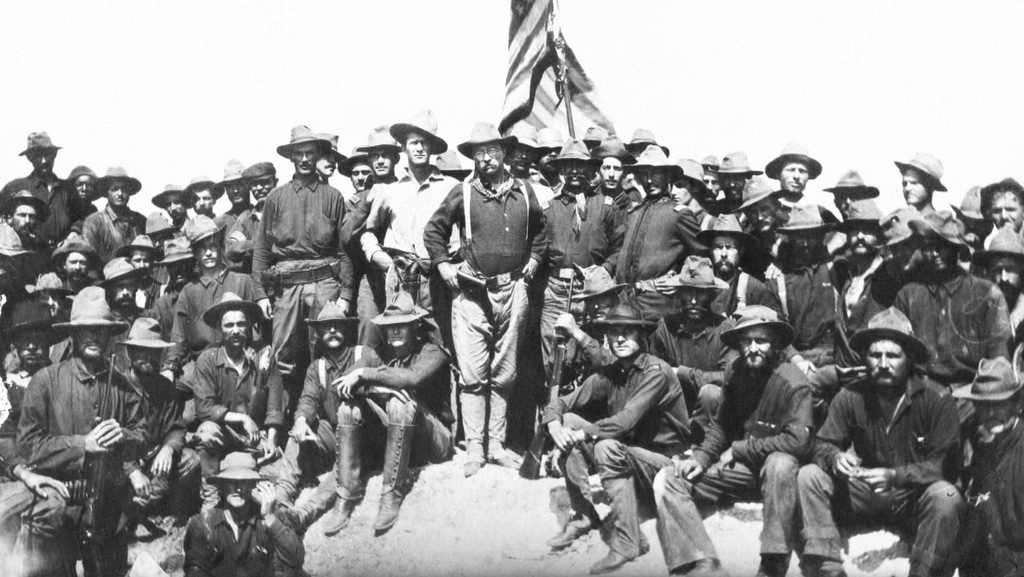

5. Roosevelt was an authentic war hero when that really mattered. His heroics at San Juan and Kettle Hill in Cuba helped him to rise like a rocket in the national arena, as he put it. Although some of this was due to the self-mythologizing of his book The Rough Riders (1899), which one friendly critic said should have been titled Alone in Cuba, nobody could argue that Roosevelt ducked the one war that came during the prime of his manhood. It is the case that on July 1, 1898, he was the most conspicuous soldier during the Rough Riders’ assault of San Juan Heights, in part because he was one of the few on horseback. He later said he would have left his wife Edith’s deathbed to participate in the liberation of Cuba. It meant something to be a war hero back then, even more than now.

6. He was America’s first and greatest cowboy president. There have been only three or four, depending on how you count: Roosevelt, Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, and LBJ. Roosevelt wrote and spoke endlessly about his life on the frontier, embellishing most of his adventures and perhaps inventing a few. When he talked about the need for conservation of the public lands and resources, nobody asked, “What does he know about it?”

7. Roosevelt knew how to squeeze the most out of the laws of the United States. The Forest Reserve Act of 1891 gave the president of the United States the power to designate National Forests by Executive Order. His predecessors had designated some low-hanging fruit, just under 50 million acres. TR used his executive authority so vigorously that in 1907, Congress passed legislation preventing him from getting any new designations in six western states. He signed the obnoxious bill, but not before he and his U.S. Forester Gifford Pinchot added 16 million additional acres in the Pacific Northwest, the Midnight Reserves. The National Monuments and Antiquities Act (1906) gave the president the authority to designate National Monuments independent of Congress by Executive Order. Though the legislation specifically said the parcels should be “confined to the smallest area compatible with proper care and management of the objects to be protected,” TR stretched that restraining clause to more than 800,000 acres when he designated Grand Canyon National Monument on January 11, 1908, as he began the last year of his presidency. He invented the National Wildlife Refuge System (Federal Bird Sanctuaries) out of whole cloth in the spring of 1903, thanks to his view that as president, he was permitted to do anything not specifically prohibited by the U.S. Constitution!

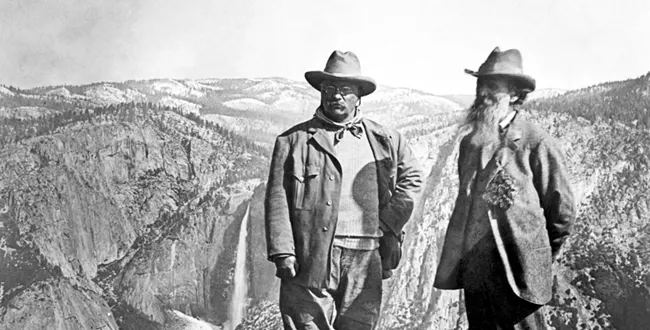

8. Finally, he had a deep, authentic, constant, and relentless passion for conservation. Bill Clinton and Barack Obama designated new National Monuments, but it is nearly impossible to imagine them camping out under the stars, eating camp beans around an open fire, or sitting in the saddle for 10 hours, threading their way through badlands country with a rifle, a piece of hardtack, and a tea bag. It would take another, longer essay to chart the origins of TR’s conservation ethos. The short answer is that as a sickly child, he read books that filled him with “the romance of the West.” When he ventured to today’s western North Dakota to kill a buffalo in September 1883, he fell deeply in love with the ridges, the buttes, the emptiness, the silence, and the endless grasslands of what the historian Daniel Flores has called American Serengeti. Recent presidents have designated National Monuments in lands they will never see nor, frankly, personally care about because it is good domestic policy. For Theodore Roosevelt, those landscapes were central to his vision of America and the most profound satisfaction of his soul.

When Roosevelt came through Medora, North Dakota in 1900, campaigning as William McKinley’s running mate, he looked out on the badlands landscape that forged his adult persona and said, “It is here that the romance of my life began.”

We are all his beneficiaries. We owe him a debt of gratitude that can only be paid by doing everything in our power to protect those landscapes from those who see them not as solace for the spirit but as a resource base to be tapped by the dynamo of extraction and economic development.