Clay recently drove the back roads from Thompson to Bismarck, North Dakota. Far from interstates, he was intensely reminded about what he loves about the state he’s long called home.

I drove across North Dakota on a recent Sunday. I want to tell you a few things about life in rural America.

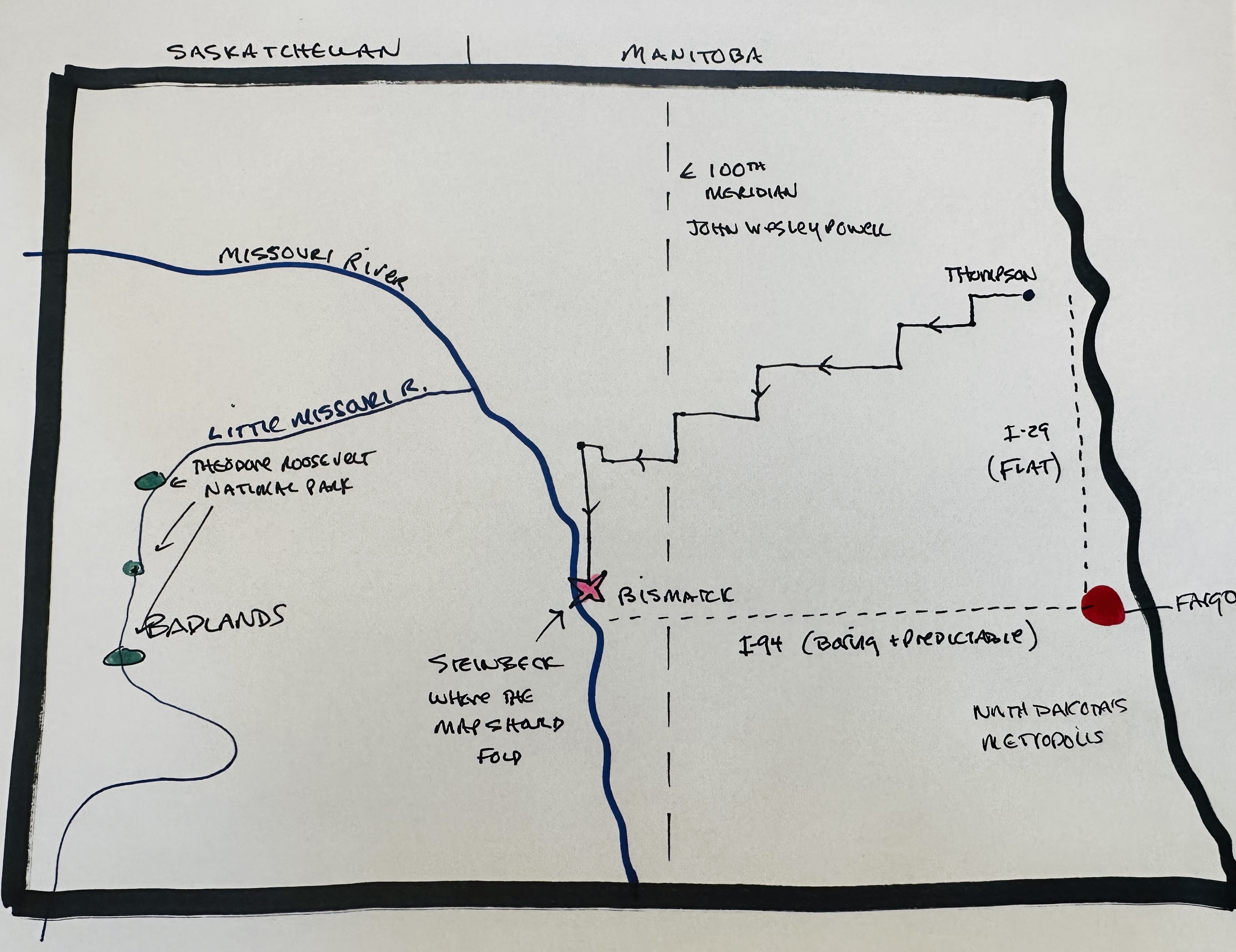

The fastest way to drive between Thompson, North Dakota, up near Grand Forks, and my home in Bismarck is south on Interstate 29 and then at Fargo west on Interstate 94. But I wasn’t in a hurry. It was a perfect Sunday in November, balmy (25 degrees), sun drenched, and windy. I prefer the back roads. In fact, I really prefer the county farm-to-market roads that have almost no traffic. So, my plan was to drive west, then south, then west, then south, piecing my way diagonally across the state without a map and without using GPS. My desultory route lengthened the time of the drive by more than an hour, but I was heavily rewarded by the opportunity to wander through small towns and see rural life. I live in Bismarck, with approximately 100,000 people. We are never unaware that we live in North Dakota, of course, but when you live in a city you can go weeks or months without experiencing true rural life. Not good. When you get out into the country, the smell of silage and manure, plus the odd road-kill skunk, reminds you that you live in the rural heartland.

North Dakota has a population of 760,000, but in the 250 miles I drove that Sunday I passed through a vast section of the state dotted by no more than two dozen roadside towns whose total accumulated population was less than 20,000, perhaps less than 15,000. Empty.

There were long stretches of blacktop highway between towns — a stretch of 20 miles, sometimes more than 30 miles. The towns I am talking about have populations between 200 and 2,500, most closer to 200. And all along that endless of ribbon of highway you see a farmstead here, a ranch headquarters there, but not many. At least half of them abandoned. Every acre is farmed, but there are fewer and fewer farmers and now many of them commute from town. At any given time had I stopped the car I would be no more than 5 or 7 or at most 9 miles from the nearest other human being. I would not have wanted my car to break down out here. I’d survive that long walk on a raw November day, temperature about 20 and the windchill registering 10 below, but it would have been an ordeal. But, had I broken down, and attempted to walk to town or the nearest farm, someone would have stopped to ask me if I needed help. That’s North Dakota. We know that our raw climate can kill. We are less trusting than we once were, but we still stop to help each other when they need it. Even strangers.

North Dakota Is Not Flat

North Dakota is not flat, but outsiders are often amused when the people of the state declare that the geography is better described as gently rolling, undulating, and contoured. The highest “peak” of the state is out west, White Butte, 3,506 feet. Most of the state measures up at about 2,000 feet above sea level. Not much obscures the horizons in any direction. No, North Dakota is decidedly not flat, except in the Red River and Souris River valleys. But it is not the Grand Tetons, either, or even the Black Hills of the other Dakota. I’ve heard someone say that driving North Dakota is like watching paint dry on a wall. Still, except for a few minutes here and there, I refused to turn on the radio.

You must imagine the countryside as essentially empty, with some high powerlines stretching to the horizon, the land rolling as if it were caught undulating and locked forever into place.

If you are not from these parts (as we say) you may not understand what we mean by wind. North Dakota is the fourth windiest state, but surely, we deserve first place. There are very few entirely windless days in North Dakota and they always make us a little uneasy. A 5-8 mile per hour wind we regard as “dead calm.” I suppose there are 250 or more windy days per year here depending on your definition of wind. And there are about 40 days in which the wind blows like a sonofabitch. Sometimes in bed at night when the wind is wild, I can hear the grit it stirs up grinding away at the synthetic siding on the west side of my house, like a million voracious nano-insects. The wind Sunday was one of the memorable ones, never less than 20 mph and often gusting up to 40 or even 50 mph. It was a buffeting wind, the kind that veers and pummels the car enough to require some strenuous steering. You expect to see Holstein cows flying overhead as in the Hollywood movie Twister starring Helen Hunt.

This intensity of wind may sound oppressive, but it was glorious. Whenever I got out of the car, I had to hold onto the door lest it be wrenched off and blown into the next county. I wouldn’t have wanted to spend the day out on foot in that wind, but it was bracing in short encounters, and it made me proud to be a North Dakotan. I know it sounds a little weird, but we North Dakotans take pride in how raw our climate can be, how punishing, blizzards at 30 below zero, snow drifting over the roads, weeks of prolonged below zero weather, the Memorial Day picnic blasted out of the park by wind, rain, even snow! Our stoic strength of character that permits us to shrug off the sometimes-lethal climate and regard ourselves as “the few, the proud, the plainsmen (and women)” makes us feel that we are somehow stronger than those pitiful Californians who live in a climate reminiscent of the Garden of Eden. Bring Arnold Schwarzenegger to Grand Forks on a January afternoon and I doubt he’ll say, “I’ll be back.”

I drove about 60 miles per hour.

On the secondary and tertiary roads, but not on the freeways, the person coming from the other direction, especially if the driver is a man, will exchange the famous rural America two-finger wave. This involves a couple of fingers rising above the steering wheel, in a deliberately informal way. You must not be too eager. You must not actually wave. There must be a studied nonchalance, a kind of rural salute.

North Dakota is a farm state. Virtually every acre is harnessed for agricultural production: wheat, corn, soybeans, sunflowers, flax, canola, cattle. By this time of year almost every field has been harvested, but every few miles I drove past a huge cornfield through which a bright green combine was slowly advancing. At the edge of the field there was parked an 18-wheel tractor trailer into which the farmer periodically emptied the combine’s full hopper of bright yellow corn kernels. When the semi was full, someone would lumber it off to the grain elevator or take it directly to the nearest ethanol plant.

The abundance of the corn harvest is staggering. All the grain elevators of the state are full at this time of year, both the old-style wooden elevators, the “skyscrapers of the plains” (now slowly disappearing) and the giant circular metal bins. Next to nearly every commercial or coop grain elevator there were huge mountains of corn exposed to the elements, sometimes two or three or even four in proximity. They looked like giant yellow Hershey’s kisses. They were 50 or more yards across and four stories high. A few of them were covered with gigantic white plastic tarps. Sometime in the next couple of months all that grain will be hauled away to market, either on trucks or trains.

I was struck with sadness as I drove by all that abundance. I know for a fact that almost none of that corn will be used to feed people, at least not directly. The great bulk of it will be burned up in ethanol plants scattered over the Great Plains and Midwest. Much of the rest of it will go to feedlots to fatten beef cattle for slaughter. Some of it will go to processing plants where it will be pulverized, liquified, and turned into the kinds of corn products that enclose your chicken nugget or rendered into a sugary syrup that will sweeten your favorite soft drink. In America only 2% of corn is directly ingested by humans — cob, creamed, or mixed with bits of other vegetables. If you want to understand the sheer insanity of the corn economy, start with Michael Pollan’s famous corn chapter in The Omnivore’s Dilemma. We plant corn with fuel (plus fertilizer, pesticides, herbicides, sometimes irrigation water) and then we … burn the corn in giant industrial plants to make … fuel. Farmers used to have bumper stickers that said, “One farmer feeds 126 people,” something like that. Feeding the world was the nobility of farming. Now we feed the furnace. Nothing noble in that. But it cash flows, with a little help from the Farm Program.

The Color of the Great Plains

You should have seen the color palate of the Great Plains on the day I drove through. The sun was bright, almost garish at times, but it was clearly a November and not a July sun. The tall dead corn stalks still unharvested in the fields were a dull raspy yellow bordering on beige. The sunflowers drooped their black heads in vast fields where every flower is the size of a dinner plate, and they all faced a single direction in a kind of tight military formation. The prairie grasses were worthy of Monet — rust colored, gray-blue, mauve, tawny, golden, beige-green. But it was the prairie potholes filled with water that stunned my senses and forced me to stop the car half a dozen times to take photographs. They were the bluest blue you can ever imagine. They were bluer than the sky. They were the blue of God. If God has a color it has to be blue — Carl Sagan’s pale blue dot, the watery planet where 71% of the surface is water. On Sunday it was blue to make you ache. It was blue as if you were seeing blue in its finest essence for the first time. Take your breath away blue. No such blue in February, no such blue in August. It’s not until autumn that the plains bring out the fullest blue of sloughs, lakelets, lakes, and streams.

I slowed to 55, then 45, then 25 as I passed through the little towns. I sometimes drove the sad Main Street off to the right or left, with many of the great old brick buildings now empty or underused, windows boarded up. The town usually has a newish bank not in the historic bank district, but out near the edge of town and it is a recent modest building, often modular, with an impressive facade. A café and two or three bars. A modest little post office in a tan brick building: Buxton 58218 (population 356), Drake 58736 (population 286).

I drove through a number of these towns during Sunday church services. At the Lutheran Church dozens of cars, at the Catholic church 20 or more, but only seven to 10 at the Presbyterian or Baptist church. More than half of the vehicles in the parking lot — SUVs, pickups, big old Buicks — have so much dirt on the back that the rear windows and the license plate are fully obscured. These are local farmers and ranchers who drove in for the service. At this time of year, it doesn’t do much good to wash the vehicle because it is almost immediately going to get dirty again. In many of these small towns the minister has driven in from elsewhere for the service. He (now more often she) has three churches every Sunday in a 40-75 mile radius.

Almost every town has a roadside stand, a Dairy Barn, a Dairy King, a King Cone, or a Tastee Barn — all carefully calibrated not to be threatened with legal action by the Dairy Queen Corporation. At this time of year, they all have 8×10 inch signs, hastily made with a black Sharpie, saying, “See You next Summer.”

Every town has a hair salon with a cute name: Shear Encounters, The Clip Joint, Hair Today Gone Tomorrow. Often with a tanning parlor in the back.

Out on the edge of the town you’ll find the implement dealers and the hitch and trailer shops, maybe the Farm Credit office. In the more substantial towns, there is usually an edge-of-town subdivision with impressive 1970s ranch style houses. These used to be the homes built by prosperous dentists, doctors, and lawyers, but these days you must drive a fairly long distance to have access to any of those professional services. Small towns on the Great Plains are mostly on life support, and they hew very close to the base of Maslow’s Hierarchy — post office, bars, café, Cenex convenience store, grain elevator, maybe an implement dealer.

On the edge of the luckier towns, a home-shop made billboard saying, “Gretchen W…r, 2019 Class B Basketball MVP” or the “Mighty Coyotes, 2004 State Wrestling Champions.” These local athletic stars are local celebrities through their whole lives. They coach, farm, or sell insurance.

Vanishing Trees

I drove by hundreds of dying shelter belts. These are long rows of trees on the north and west sides of farmsteads throughout the state. They were planted in the ’50s and ’60s and ’70s. By now they have mostly reached the end of their natural life cycle. But they are not being replanted. Shelter belting was one solution to the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal established the Soil Conservation Service (1933) to combat wind erosion and restore the soil health of the farms and ranches of the Great Plains. In my youth these shelter belts mattered much more than they now do — we think we are immune to another Dust Bowl, silly humans — and it was a very big deal to win the County Soil Conservation Award for the best shelter belts. Aerial photos were taken of the exemplary farm and the farm family was celebrated at the annual Soil Conservation Banquet, at which the family spokesman said, “we don’t think our shelter belts are better than anyone else’s, but we’re proud of the work we have done to protect our fields and prevent the dust from blowing into the house as it did in Grandpa’s time.”

One southern plains farmer later said, “The dust storms came over us almost every day. As far as possible we hung wet sheets and towels over all the cracks, day after day. And we kept on sweeping. We swept whole washtubs full of dust off the floor.”

Now North Dakota’s shelter belts are dying, and it is fashionable to bulldoze them down and into huge pyres in the increasingly gigantic fields. Some of them will be burned if there is ever a windless day. They are not being replanted. North Dakota is the state with the fewest trees and soon there will be dramatically fewer trees. Most of the trees in North Dakota were planted by homesteaders and their descendants.

I think of the hard work of farm families to plant those rows and trees and find a way to keep them alive though the dry years and through the sometimes-savage winters. Some of the trees had to be watered by hand, bucket by bucket from the well. Such trees — elms, evergreens, Russian olives — don’t water themselves, and almost no planted tree survives in North Dakota without a considerable amount of human intervention.

On this 250-mile drive I saw only three MAGA or Trump signs (or flags), none for Biden, of course. But the relative sparsity of Trump signs must be meaningful. Six years ago, they were ubiquitous on the Great Plains. I believe nearly the same percentage of North Dakotans would vote for Trump if he is the 2024 Republican nominee, but the ecstatic years seem to be over, and the Trump phenomenon feels weaker in 2023 than it was in 2016.

I came up over a hill and there was a gleaming white wooden prairie Lutheran church, with a sturdy and elegant steeple. The gloriously white box church appeared so suddenly that I nearly burst into tears. The vaulted windows were tinted opaque, but they were not of stained glass. When it was built back in the ’40s, North Dakota’s rural life was not yet in decline. On the Sunday I drove through, the parking lot was empty at 1:17 p.m. but earlier that day half a dozen cars had rolled onto the grass west of the church.

Soon after that I stopped the car to take a picture (and a leak — such is North Dakota’s emptiness). I stretched as high into the air as I could. The wind was … bracing, loud, boisterous, aggressive. This is going to sound strange, possibly even demented, but this is why I live here. This is what I love about North Dakota. You cannot live here without frequently being made aware that you live in a punishing sub-arctic climate. “This is a glorious day,” I shouted but whatever I had to say was simply swallowed up by the winds and the sheer vastness of the Great Plains. I was alone on a vast and open landscape. I don’t think even God could hear me through the wind.

There are rock piles on almost every section of land, which means at least one per mile as you drive the state. These are rocks (many of them boulders — basketball size or larger) that were left here during the last ice age, which was only yesterday (15,000 years ago) in geological time. Those rocks just didn’t show up at those tall piles. Each rock was picked up or dug up by a grumbling member of a farm family, and lugged to the back of a pickup or, later, the scoop of a front-end loader. This is backbreaking labor, exhausting and grueling labor, but it had to be done. Every 10- or 12-foot-high rock pile represents hundreds of hours of the kind of labor we associate with Siberian gulags or Fred Flintstone at Slate Rock and Gravel. Nobody in history ever volunteered to haul rocks. Every rock in every pile (tens of thousands in the state) could tell a story of the struggle of farmers to scratch out modest prosperity on a forbidding and difficult landscape. Farm children of the 21st century cannot even imagine that life, and their aging grandparents can only groan as they think back.

You cannot drive more than 20 miles on any two-lane highway in North Dakota without seeing a billboard saying, “Abortion Stops a Beating Heart.” Needless to say, there are no pro-choice billboards anywhere in North Dakota.

I saw hunters stretching near the tailgate of their pickups, one dressed in solid hunter’s orange, including a hoodie, the other entirely in camo. They are drinking schlock beer out of cans.

I didn’t see a single pedestrian all day long.

The tallest things out on the plains are radio and television towers. In the towns the old wooden grain elevators — classical Grant Wood grain elevators — are the tallest buildings. There may be a four-story brick building downtown that once had an auditorium and even lured some opera to the prairie a hundred years ago.

So, I spent the day driving and musing and daydreaming and gazing out on the endless plains and thinking about rural life, which was once the backbone of North Dakota and the source of the character of the people — pragmatic, modest, God-fearing, thrifty, hardworking, and small “c” conservative. Had I driven the interstate highways I would have arrived home sooner (and there would have been rest areas!). But I would have driven on autopilot, both the machine and the man, and I would have missed so much that I love about living in this stark improbable place.

When I saw the billboards north of Bismarck advertising car dealerships and national chain restaurants, I felt deflated. When will I next have so magical a day in the North Dakota outback?