Day Three, Afternoon: Fort Robinson, Nebraska

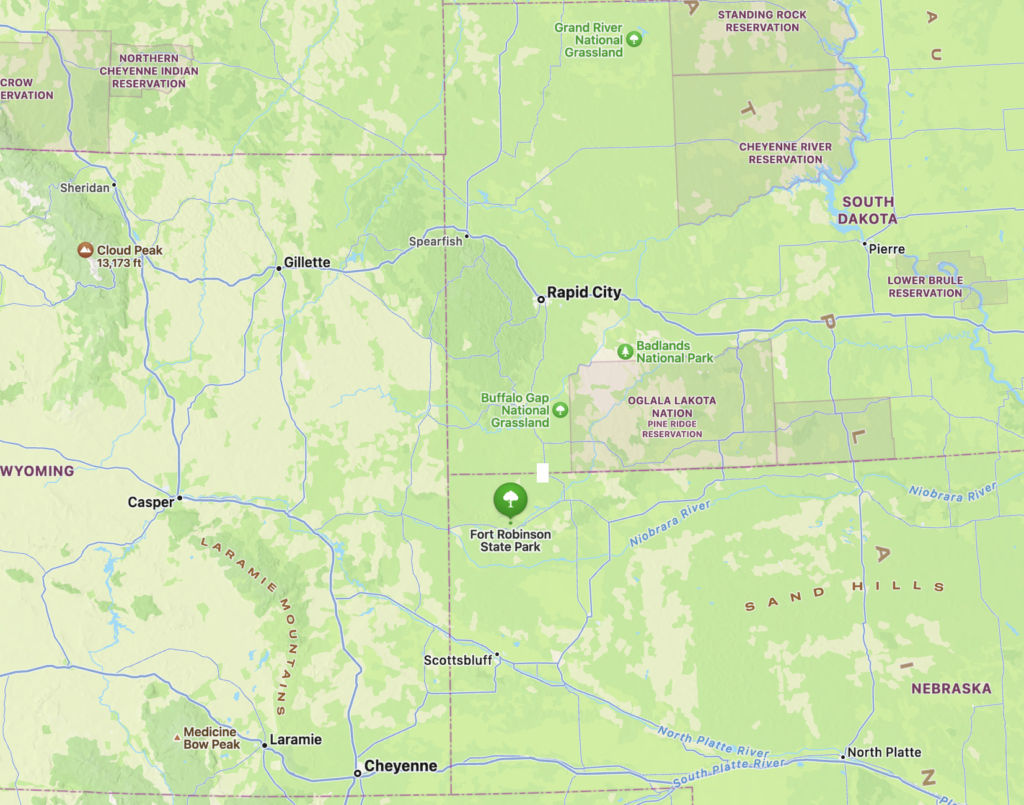

Leaving Badlands National Park Clay stops at Fort Robinson in Nebraska as he continues his drive from Bismarck to Vail, Colorado.

Leaving South Dakota, I drove south to Fort Robinson in Nebraska, the site where the great Oglala leader Crazy Horse died. He was killed unnecessarily on September 5, 1877, at about 33. The history of the “Indian Wars,” as they used to be known, makes you think about that day repeatedly. The great Oglala leader had finally surrendered, though he had never been defeated in battle. After a long winter of dawn attacks up and down the plains by the U.S. Army, he would not let his people suffer any longer. He lived peacefully but restlessly in his uncle Spotted Tail’s camp 30 miles to the east. Rumors passed like wildfire that he was about to break out, disappear in the night, maybe round up some like-minded young men. He was under intense pressure from all sides of this complicated story — the accommodationists, the absolutists, and everyone in between — and he clearly was not cut out to be a loafer-about-the-fort. He had been promised a reservation on his beloved Powder River in today’s Wyoming. The U.S. government did not attempt to keep that promise. He was so eager to return to the intermountain plains that he told one of his white supervisors that he would be willing to scout in America’s war against the Nez Perce in 1877.

Back in Chicago and Washington, D.C., the government decided that Crazy Horse must be arrested and taken as far away as possible from the Great Plains. They made this decision without communicating with those in the arena, and they knew that Crazy Horse would never agree to this. They’d have to lie to him and lure him into Fort Robinson on pretense. Then they would grab him and spirit him away forever. They planned to maroon him in the Dry Tortugas off the coast of Florida — a free man who had spent his life on the semi-arid Great Plains. He rode reluctantly into Fort Robinson with an ominous escort. When he got to the log structure where he was “to have a parley with the soldier chief,” as the poet John Neihardt put it, Crazy Horse immediately realized what would happen. So, he whipped out a butcher knife and threw himself into the crowd that had gathered there — to escape or die trying to escape. A common soldier thrust a bayonet into Crazy Horse’s kidney from behind. That was enough to extinguish the life of the great strange man of the Oglala.

I go to the site of his death whenever I am nearby. I visit the killing site because it reminds me in a very stark way of the “cost of empire,” what white America chose to displace to remake the continent in its image. If you are trying to describe the Resistance to the white conquest of North America, the Lakota seem to take their place as the leading trope. This story embodies the whole with tragic nobility and a profoundly compelling narrative.

As I sat in what is now a state park and recreation center, I remembered lines from John Neihardt’s great poem, The Death of Crazy Horse. I couldn’t recite it smoothly, but throughout the rest of the day, I could put it back together in my memory. Neihardt, the poet laureate of Nebraska, gave much of his genius to the challenge of understanding Native American culture and writing about its fatal encounter with the Europeanization of the continent.

I have severe doubts about the wisdom of rebuilding the log structures at the assassination site. For one thing, I’m not sure I want to mar the open grass space on which the killing occurred. I’m for rebuilding Lewis and Clark‘s Fort Clatsop and other forts and compounds in the West. But the parade ground of Fort Robinson seems like a sacred space. Nor do I relish the idea of fort buffs — and they are legion — rolling up to the rebuilt structures and imagining life in the good old West. This is a place of solemnity.

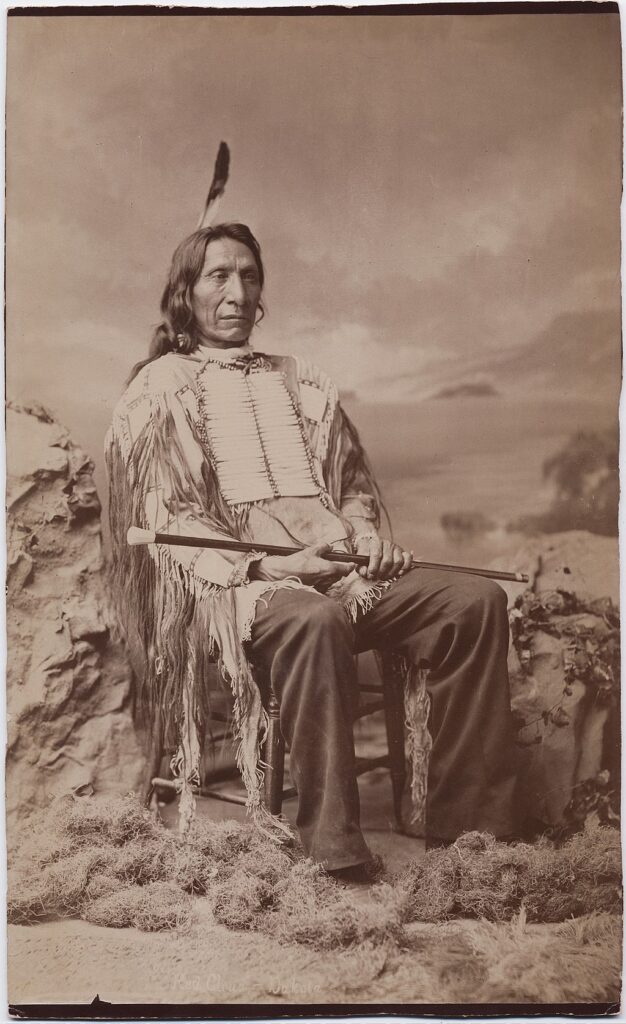

Crazy Horse has become the national symbol of the Resistance. But he needs to be seen as one part of a triumvirate of Lakota leaders who were trying to find a way to survive the coming of the white juggernaut. Red Cloud (1822-1909) was the great Oglala war leader during the Powder River War in 1868. He humiliated the U.S. Army on the Bozeman Trail. He won the war with considerable help from young Crazy Horse. The U.S. had to withdraw from its forts on the Bozeman Trail and enter a treaty with the Lakota (the Great Sioux Treaty of 1868), as generous to a Native people as any American treaty has ever been on paper. But after his stunning victory, Red Cloud dedicated the rest of his life to diplomacy. He was done fighting wars against the white interlopers. Today he is usually characterized as an “accommodationist.” However, that term does not do justice to his continual and often successful advocacy for his people against impossible odds. The second member of this triumvirate was Sitting Bull (1831-1890), the Hunkpapa leader who was one of the masterminds of the victory at the Little Bighorn in 1876. Sitting Bull was a great warrior but was more critical as a seer and civilian leader. He fought the white armies when necessary and held on just as long as he could in Canada. In the end, Sitting Bull surrendered on July 20, 1881, and took up a cabin at the far end of the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. He believed that he could live out his life on the margins of white civilization, having made as few accommodations to white demands as possible. He was killed in a bungled arrest attempt at dawn on December 15, 1890. He was minding his own business.

Thus, Crazy Horse was cut down — as irredeemable — in 1877. Sitting Bull was cut down — as irredeemable — in 1890, just two weeks before the Wounded Knee Massacre. Red Cloud, the diplomat, lived until December 10, 1909. He met Theodore Roosevelt and other Presidents of the United States. He died the same year the Whitestone Hill monument was thrown up by the settler civilization of North Dakota.

I go to see the death site of Crazy Horse (as I go to Sitting Bull’s cabin site on the North and South Dakota border because they represent the Resistance. I don’t identify with the Resistance, but I respect it deeply. I know my complicities. And I find it impossible not to feel a stirring of the deepest admiration for the Lakota’s refusal to bow to the inevitable.

In June, Clay drove from his home in Bismarck, North Dakota to Vail, Colorado. A focus of Clay’s two-week road trip was exploring little-remembered sites of tragic encounters between Native Americans and an expanding, westward-moving white population of the 1860-1880s. Clay’s stops included a battle site at Whitestone Hill in North Dakota in 1863, as well as the spot in Nebraska where Crazy Horse was killed in 1877, and Colorado sites commemorating the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864. Along the way, Clay also visited the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site, the U.S. National Grasslands, and a forgotten mountainside in western Colorado, where the federal government detonated a nuclear bomb in 1969 in an experiment to explore the peaceful use of atomic weapons. And — as in all good journeys — unexpected and unrelated roadside distractions provided plenty of ways to think about America.