What happens in the gap between one administration and the next, especially when the outgoing president is unavailable? This “leadership gap” has had an intriguing influence on U.S. History.

I’ve been reading about the U.S. presidency lately.

One thing that struck me in reading Robert Caro’s magnificent Passage of Power: The Years of Lyndon Johnson was what happens in the gap between one administration and the next, especially when the outgoing president is unavailable for consultation. This “leadership gap” got me thinking about this phenomenon in American life. Here are three examples:

The Tragedy of Meriwether Lewis

Meriwether Lewis was young enough to be Thomas Jefferson’s son, and Jefferson had no son. Lewis’ father died when the boy was only 5. The Lewis family plantation was close to Monticello. Jefferson had friendly relations with Lewis’ parents. When Jefferson became president in March 1801, he summoned Lewis from the frontier army to live with him in the White House and serve as his correspondence secretary. For more than two years, they lived together, usually, the only two white individuals to live in the mansion.

Jefferson recognized that Lewis had several problems. He drank too much and too often. And he was not a very reliable communicator. Still, Jefferson declared in 1813 that there could have been no better choice for the great exploration adventure that would become the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Lewis had specific qualifications Jefferson believed: he was habituated to the woods, was a good amateur botanist, an excellent leader of men, painstakingly accurate in his written observations, and reasonably familiar with Native Americans. Jefferson thought the physical rigors might cure Lewis’ melancholia of the transcontinental journey.

The expedition returned to St. Louis in September 1806.

By 1808, both Jefferson and William Clark knew that Lewis was starting to come apart. Jefferson had made Lewis the governor of the Upper Louisiana Territory. Lewis had been tardy taking up his duties and was finally overwhelmed by trying to govern an unruly and violent frontier territory, where Spanish and French nationals clashed with the new Anglos about all sorts of policies. Dispossessing the Osage from their homelands in the least appalling way was also a significant burden. Meanwhile, the national government was hundreds of miles and a month’s mail service away.

Jefferson retired in March 1809 and returned to Monticello to putter in his garden and live out his days. His protégé James Madison succeeded him in the presidency. By now, the War Department was fed up with Lewis, who was a lousy communicator and who had engaged in unauthorized expenditures of government money to try to get the Mandan leader Sheheke home to his earthlodge village in today’s North Dakota. Lewis received a fierce letter of rebuke from the War Department in July 1809. It accused him of unacceptable silences, conflict of interest, and unauthorized use of financial vouchers, several of which the War Department said it would not reimburse.

This snarky official rebuke threw Lewis into a cocktail of fury and shame. He determined to go to Washington to try to clear things up. There were rumors that the War Department would formally recall him. And he had yet to write a single page of his proposed three-volume report on the expedition. He was drinking to excess. He suffered from malaria. He was dosing himself with an opium derivative called laudanum.

His life was in disarray. But what sent him over the top was the letter of rebuke from a government he had served honorably. His integrity and sense of honor had been challenged by a government he had loyally served.

Lewis committed suicide on the night of October 11, 1809, at a squalid hut on the Natchez Trace about 75 miles from Nashville.

IF JEFFERSON HAD STILL BEEN PRESIDENT, this crisis almost certainly would not have happened. Jefferson loved Lewis, and he understood his growing fragility. With his exquisite tact and generosity of spirit and loyalty, Jefferson would have found a way to make sure Lewis was made aware of his deficiencies without shaming him or challenging his integrity. In other words, I doubt very much that Lewis would have committed suicide had Jefferson still been in office. He would have eased Lewis through this crisis.

But when Jefferson left Washington in March 1809, he washed his hands of “the disagreeable business of politics” once and for all. He promised that he would not meddle in the administration of his best friend and successor, and he cut himself off from further communication with the Washington establishment. Like Cincinnatus (and George Washington), Jefferson wanted to sit under his vine and his fig tree in the mountains of Virginia and write handsome letters to his friends in the Republic of Letters.

Madison was no great friend to the American West, and he was not as patient as Jefferson had been with Lewis’ inadequacies. In the notorious letter of rebuke, the Secretary of War told Lewis that he had briefed President Madison, and the President approved of the way he was handling it.

Ouch.

It was the gap between administrations that killed Meriwether Lewis. If Madison had picked up the phone and called Monticello, he and Jefferson would have found a way to rein Lewis in without precipitating an existential crisis in an American hero and very gifted (if troubled) young man.

Meriwether Lewis was a victim of the gap.

Truman Inherits the Atomic Bomb

Franklin Delano Roosevelt let his Democratic insiders choose Missouri Senator Harry S. Truman as his running mate in 1944 when FDR stood for an unprecedented fourth term. At the time when these decisions were made, Roosevelt was gravely ill (in fact, dying). Still, no attempt was made to choose a vice president with previous executive experience or someone well-versed in the perilous world situation. Nor during the 82 days that Truman was vice president did FDR or his advisers make any attempt to brief him on the many important, even urgent, issues that the president or his successor must attend to.

Franklin Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945, at Warm Springs, Georgia.

That afternoon, Truman was summoned to the White House, where he took the oath of office. That same afternoon, he learned of the Manhattan Project for the first time — the emergency mission to build an atomic bomb in time to affect the war’s outcome.

Think of that. Truman had no clue that we were about to test a weapon of mass destruction that could vaporize 60,000 human beings instantly and condemn tens of thousands more to slow agonizing death by way of radiation sickness. Truman had only a few weeks to decide whether to deploy the atomic device on Japan; now that Hitler was dead, the war in Europe was over, and it turned out that the Germans had not even been within sight of building such a device.

The “accidental president,” as he has been called, permitted the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, though he did not choose either target or determine the dates of the attacks.

When Robert Oppenheimer came to the White House after the war to wring his hands about his own agency in the bombings, Truman called him a crybaby and said, “Don’t bring that fellow around here again. All he did was make the bomb. I’m the guy who fired it off.”

What if Franklin Roosevelt had lived through the war’s end in both the European and Pacific theaters? Would things have been the same, or might history have unfolded differently? Would FDR have deployed the atomic bomb on Japan? Without warning? Two detonations just three days apart? We don’t know. We have no way of knowing.

But this much seems clear. It was unfair to put that burden on Harry S. Truman. If he had been assigned as VP to supervise the completion of the work at Los Alamos and been fully briefed from the moment he accepted the nomination for the vice presidency, he would have been in a better position to ruminate on what we were about to loose upon the world. Who knows if that would have made any difference in his thinking? But, given the gravity of nuclear weaponry and its profound threat to the future of the world, it would have been better if FDR had lived to make the hard decisions or left a few memos about what he meant by unconditional surrender, the postwar settlement, or the use of an unprecedented weapon of mass destruction.

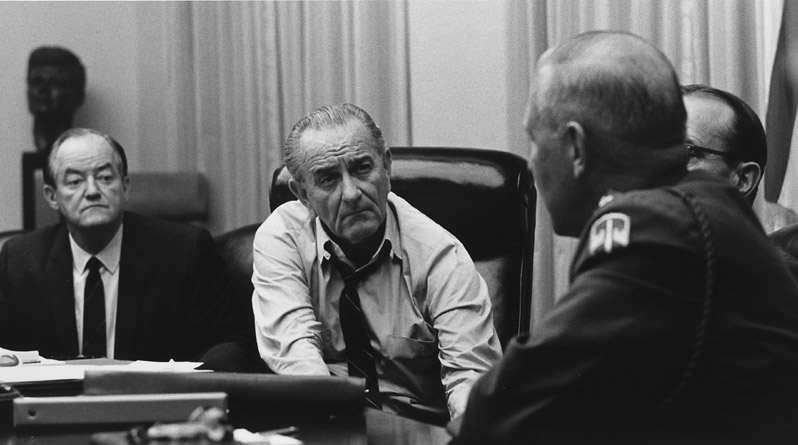

Lyndon Johnson’s and the Martyr’s Legacy

Lyndon Johnson was chosen to be John F. Kennedy’s vice president in 1960 for political reasons. He and Jack Kennedy could not have been more different in deportment, style, education, or background. Johnson never felt he was permitted to be a real factor in the Kennedy administration.

JFK was cut down by a sniper or snipers on November 22, 1963, in Dallas. Johnson took the oath of office on the presidential plane that afternoon before it took off from Love Field in Dallas.

Johnson knew much more about John Kennedy’s government than Truman knew about FDR’s. Unlike Truman, he had not been left to languish on the sidelines. He was better positioned to handle the post-Kennedy presidency than Madison had been with Jefferson or Truman with Roosevelt.

In the wake of the assassination, Johnson felt that he had a moral duty to pursue JFK’s legislative and political agenda. He was a much better legislative wrangler than JFK had been, thanks to his in-your-face, at-your-lapels political manner and because he had been the senate majority leader (1955-61) in the years leading up to Kennedy’s election in 1960.

Johnson’s commitment to fulfilling JFK’s mandate had two enormous consequences, one good, one not so good.

Kennedy’s Civil Rights legislation was stalled in Congress and was unlikely to get Congressional approval on his watch. Kennedy was not the kind of man who horse-traded with Southern senators, or cajoled, or threatened, or flattered, or entrapped potential supporters. Thanks to the vast national outpouring of grief after November 22nd and a collective desire to honor the slain president, coupled with Johnson’s political genius, the United States passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Arguably, those two gigantic achievements in American political life would not have happened, at least not as soon, had it not been for the gap between the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

The other legacy is tragic. Johnson believed his duty was to pursue the American commitment to South Vietnam to a successful conclusion. He began to send significant numbers of American soldiers to Vietnam in 1965. By 1969, we had 543,482 troops in Vietnam, with no end in sight, no light at the end of the tunnel, and no strategic way to obtain peace with honor, as Johnson’s successor, Richard Nixon, put it.

Was John F. Kennedy planning to wind down America’s presence in Vietnam as some of his closest friends and advisers claimed and many historians have concluded? JFK’s closest friend, Kenny O’Donnell, says he planned to get out or wind down after the 1964 election. Is this true? Did Lyndon Johnson misread Kennedy’s intentions? Presidential historian Theodore White thought so and said if LBJ had understood JFK’s plans, we might have saved the lives of millions of Vietnamese and 58,000 Americans.

We cannot know. I’m skeptical of the liberal progressive argument that LBJ misread Kennedy’s intentions (to wind down) and, therefore, plunged the United States into the quagmire that led to the collapse of two presidencies: Johnson’s refusal to run again in 1968 and Nixon’s demise in 1974. Kennedy gave mixed messages about his intentions in Southeast Asia, partly because he was genuinely uncertain of what was in the best interests of the United States. We know, however, that Kennedy was a Cold Warrior with a great deal to prove in the arena of military manliness, particularly after Nikita Khrushchev eviscerated him at their summit in Vienna in 1961.

We cannot know. But if Kennedy had lived to old age, and Johnson took over (say, after a one-term JFK presidency), he would have been in a position to get the advice of his predecessor as he deepened our involvement in Vietnam. If LBJ and Robert Kennedy had not been bitter enemies and political rivals, Johnson might have spent hours with RFK trying to make sense of his brother’s geopolitical legacy.

The gap brings opportunity and peril in the American constitutional system. Harry S. Truman should never have been placed in the nearly impossible situation he inherited on the afternoon of April 12, 1945. James Madison should have protected Jefferson’s protege Lewis from his bureaucratic detractors, none of whom had ever governed a far-flung territory or drunk from the source of “the mighty and heretofore deemed endless Missouri River.” Lyndon Johnson tried desperately to do the right thing by his illustrious and mythologically infused predecessor. Still, in the end, he had to make his own decisions, with the gravest consequences for tens of thousands of Americans, millions of Vietnamese, and America’s standing in the world.

I’m fascinated by these interstices. There is a book here that still needs to be written.