Days Four to Six: Laramie, Wyoming to Sand Creek and Denver, Colorado

Clay drives into eastern Colorado to spend time at the site of the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre and then to Denver to visit an exhibit on the tragic event at the History Colorado Center. This was part of Clay’s extended road trip from Bismarck to Vail, Colorado.

To visit the Sand Creek Massacre site, far out on the eastern plains of Colorado, you must want to make the trip. It is not on the road to anything. I’m a child of the plains, but the plains of eastern Colorado seem infinite in every direction — narrow blacktop roads with little traffic. CO 96 is one of my top five roads in America; stark. Here, a hopeless village every 20 or 40 miles, with a grain elevator, a bar or two, perhaps a school, a couple of gas stations, maybe a grocery store with wilted lettuce, and — stunningly — marijuana dispensaries in every town!

I got to the Sand Creek site shortly before it closed for the day. Imagine an endless sea of grass in every direction. In the distance, a thin line of cottonwoods and willows like a dark green thread undulating across a sea of grass. This is Big Sandy Creek. And here, on November 29, 1864, Colonel John Chivington and 675 members of his Colorado militia attacked a sleeping village of mostly Cheyenne and Arapahoe women and children. The men were out hunting at the time, according to Native tradition. And even though the Cheyenne had been granted a kind of guaranteed asylum far on the open plains, 175 miles from the village of Denver, Governor John Evans issued a proclamation in 1864 making it legal for anyone to kill Native Americans in Colorado. Denver, at the time, had a population of approximately 3,700 people. They had come as gold seekers.

The sign at the gate of the Sand Creek site calls on visitors to “respect sacred ground.” I stood alone on the open plain beneath the sky dome for a long time, trying to make sense of “the Sand Creek Massacre.” Here’s what happened that day: a dawn attack, no warning, hundreds killed, women and children butchered, body parts carved out and taken back to Denver as trophies. We know why it happened. White people were going to take the continent, and anyone who got in the way would be neutralized or made to disappear. But what we don’t know is why it had to happen. I tried to imagine what it would be to want Native Americans exterminated, to violate treaties with a shrug. I tried to imagine the bloodlust and the desire to bring back a woman’s body parts as a trophy and be cheered for by adoring crowds in Denver. I tried to understand the mindset of the editors of the Rocky Mountain News, who wrote heroic editorials to celebrate the atrocity. A few soldiers refused to participate in the massacre, openly protested, and later wrote candid accounts of what happened. They were regarded as traitors and punished for challenging the Colorado leaders, civilian and military, who organized the slaughter.

It took a long, long time, but on December 3, 2014, Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper stood on the steps of the Colorado State Capitol and apologized to the Cheyenne and Arapahoe people for the Sand Creek massacre. He did not understate the issue: “We should not be afraid to criticize and condemn that which is inexcusable,” Hickenlooper said, “so I am here to offer something that has been a long time coming. On behalf of the good, peaceful, loving people of Colorado, I want to say we are sorry for the atrocity that our government and its agents visited upon your ancestors.” Atrocity is a big word. Still, the Governor took less criticism from the Right for “atrocity” than for “apologizing for America.”

History Colorado Center: A Right and Wrong Approach to Historical Interpretation

I returned to my car and drove west to Denver. I wanted to see the Sand Creek Massacre exhibit at the History Colorado Center. I was the first to arrive on a Saturday morning.

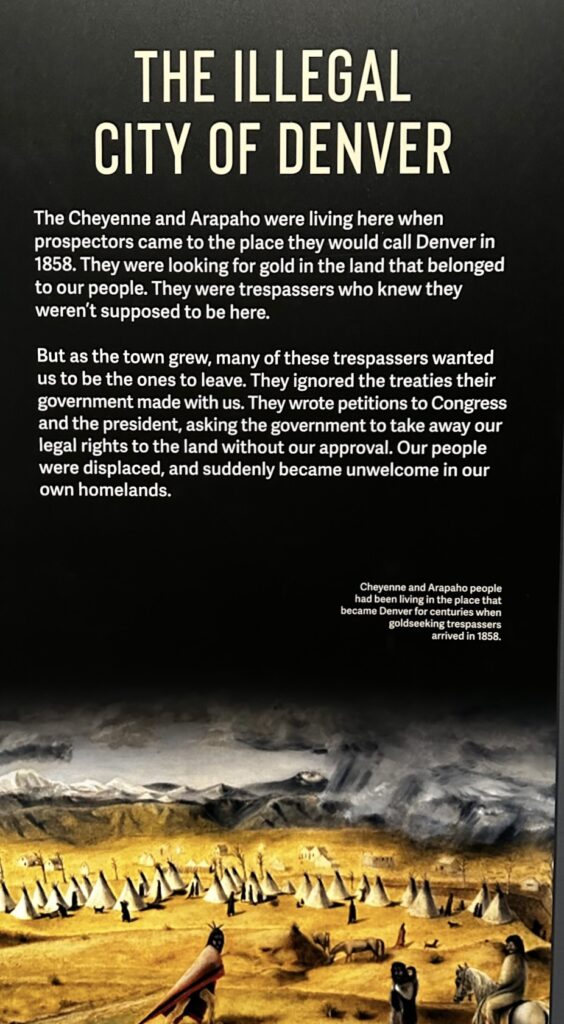

It’s a fabulous exhibit. Dark. Dark in its recounting of the atrocity and dark in its exhibit aesthetics. The story is told entirely by the Cheyenne and the Arapahoe. The “We” that appears on every panel are the Cheyenne and the Arapahoe. The minute you walk into the special section of the History Colorado Center, you have to rethink who “We” are.

The current exhibit has its own extraordinary origin story. The history center mounted a previous Sand Creek exhibit in 2012, but — if you can imagine it — it did so without any significant consultation with the Cheyenne and Arapahoe. This was 2012, not 1980. That exhibit emphasized a “clash of cultures,” as if the History Colorado Center administrators’ only excuse was that they were too busy at the time developing new presentations to inaugurate a new building. The tribes protested vigorously, and officials removed the exhibit in 2013.

The current exhibit opened in 2022. Although the Cheyenne and Arapahoe hesitated to participate in what they first assumed would be another whitewash, they soon understood that the history center had learned from its mistake and truly wanted fundamental Native input. Every detail, image, and word was vetted and approved by the descendants of the people who fought and died there in 1864.

The new exhibit pulls no punches. One of the first panels explains: “We commemorate the family members who were killed that day, even as we continue living with the unresolved trauma the massacre left behind for Cheyenne and Arapahoe people.” Strong words. Still unresolved trauma, 159 years later. Then: “This exhibit tells the stories of the worst betrayal that ever happened to Cheyenne and Arapahoe people.”

The titles of the exhibit panels tell the story:

Invasion

The Illegal City of Denver

Discarded Treaties and Broken Promises

We Tried to Make Peace Again and Again

Massacre

Weapons of Mass Destruction

Massacre, Not a Battle

Aftermath

They Were Never Punished

A Sickening Parade of Horrific Atrocities

Reparations WithheldSome believe this exhibit goes too far in the other direction, that it is too hard on the white frontier civilization that did this. But how could it be said to go too far?

Native Americans displaced from their homeland, now living 175 miles from the village of Denver, minding their own business, under a peace flag protecting them from molestation, attacked without warning in a genocidal mission bearing the official stamp of the Colorado government. Women and children butchered and cut up as war trophies

The best you could say is that the white folks thought they had a manifest license to take the West as politely as possible but as ruthlessly as necessary from the Natives.

But there is good news. The exhibit is not only winning national acclaim, but it is a template and invitation for other enlightened institutions to follow suit, allowing Native Americans to tell their story. A new era is dawning, and we are beginning to see results, some highly discomforting. This is a necessary part of healing, of the “truth and reconciliation commissions” that can lead to a more harmonious future. I’m glad I lived to see it. I know this leads to discomfort, including for me. Where the heart is good, forgiveness and reconciliation can follow.

And the story at History Colorado ends with a panel entitled Running to Heal. Every year since 1999, Arapahoe and Cheyenne people, mostly young people, have begun at the massacre site and run to Denver, a distance of 173 miles. Scores of people join the Sand Creek Massacre Spiritual Healing Run every year, sometimes hundreds.

In June, Clay drove from his home in Bismarck, North Dakota to Vail, Colorado. A focus of Clay’s two-week road trip was exploring little-remembered sites of tragic encounters between Native Americans and an expanding, westward-moving white population of the 1860-1880s. Clay’s stops included a battle site at Whitestone Hill in North Dakota in 1863, as well as the spot in Nebraska where Crazy Horse was killed in 1877, and Colorado sites commemorating the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864. Along the way, Clay also visited the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site, the U.S. National Grasslands, and a forgotten mountainside in western Colorado, where the federal government detonated a nuclear bomb in 1969 in an experiment to explore the peaceful use of atomic weapons. And — as in all good journeys — unexpected and unrelated roadside distractions provided plenty of ways to think about America.