President Thomas Jefferson entrusted Meriwether Lewis with the first great exploration of the American West. At the journey’s successful completion, both men held high expectations for a book worthy of the singular accomplishment and the Age of Enlightenment of which it was a part.

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, leaders of President Thomas Jefferson’s Corps of Discovery returned to St. Louis on September 23, 1806. Three days later Clark terminated his expedition journal with the words, “a fine morning we commenced wrighting &c.” Nobody is altogether sure what “wrighting” Clark had in mind — letters, probably, and perhaps a fair copy of the journals.

What we do know is that Meriwether Lewis never published his projected three-volume account of what he called “my late tour.” His grand prospectus, published in April 1807, promised a narrative volume, followed by a volume on the geography of the West, thoughts on the fur trade, ethnographic materials on Native Americans, and “reflections on the subjects of civilizing, governing and maintaining a friendly intercourse with those nations.” The third volume would be solely devoted to scientific subjects, together with 23 Native vocabularies, and dissertations on volcanic activity in the Louisiana Territory, the “muddiness of the Missouri,” and the treelessness of the Great Plains.

After Lewis’ death in October 1809, his publisher informed Thomas Jefferson that “Govr. Lewis never furnished us with a line of the M.S. nor indeed could we ever hear any thing from him respecting it tho frequent applications to that effect were made to him.” Some scholars (I among them) believe that the finest passages in the extant journals of Lewis were part of a draft of what would have been his first volume, but if that is so, he never forwarded any of that to the publisher in Philadelphia. We can only imagine Jefferson’s chagrin when he received this letter in November 1809. Now what?

In 1807, Sergeant Patrick Gass was the first to publish an account of the expedition with the help of a ghostwriter. Lewis dismissed the Gass account as “spurious,” and warned the reading public that they should expect nothing but “merely a limited detail of our daily transactions” from books by lesser members of the expedition. One unfortunate result of Lewis’ haughty rebuke to Gass and Robert Frazier, who had also published a prospectus, is that Frazier’s journal disappeared and has never resurfaced. Thus, we lost what certainly would have been a valuable addition to the expedition record.

Lewis died on October 11, 1809, on the Natchez Trace. In his trunks were found “Sixteen Note books bound in red morocco with clasps,” “One bundle of Misceleans. paprs,” maps and charts, “Musterrolls,” vouchers, a bundle of expedition vocabularies, a memorandum book, “six note books unbound,” and “One do. [i.e., bundle] Sketches for the President of the U. States.” Not all of these documents have been identified, even by the great Donald Jackson, but it is generally believed that most of the expedition’s journals were in those trunks. The trunk containing Lewis’ papers eventually found its way to Washington, D.C., where Clark took possession of it at Jefferson’s request. If the trunks really contained charts and “Sketches,” they seem to have been lost.

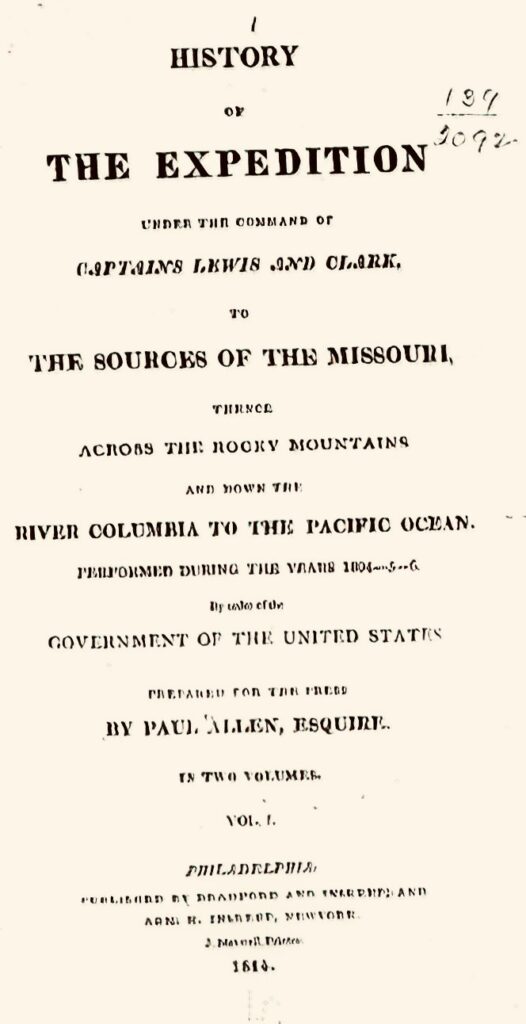

Jefferson met with William Clark at Monticello sometime in late 1809, and instructed him to travel to Philadelphia, learn what he could about the status of the publication project, and do whatever it took to see the journals into print. This must have been a painful meeting. Jefferson did not know Clark well; he regarded the expedition as Lewis’ command and achievement. It is fascinating to note that the action item of the meeting was to get the journals published as soon as practicable, and apparently not to investigate the mysterious death of one man’s protégé and the other’s closest friend. Clark pursued the publication project with his usual thoroughness and reliability, but even so, the one-volume Biddle edition, entitled, History of the Expedition under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark, did not appear until sometime in 1814.

The Backstory: Getting the Expedition Journals Into Print

On December 11, 1809, Jefferson wrote to Lewis’ publisher to inform them that Clark “is himself now gone on to Washington, where the papers may be immediately expected, & he will proceed thence to Philadelphia to do whatever is necessary to the publication.”

In January 1810, just three months after the death of his friend Lewis, Clark was able to write a memorandum on the status of the project. This was a list of things he needed to check on in Philadelphia and a partial list of what would be the contents of the publication he had in mind. The memo included notations on botanical data, calculations of latitude and longitude, engravings of animals and Native Americans, maps, vocabularies, and “Natural Phenomena.” Clark noted that he wanted to “Get some one to write the scientific part & natural history” of the expedition, and he wondered “If a man can be got to go to St. Louis with me to write the journal & price.”

In Philadelphia, after a painstaking search for every individual Lewis had hired to work on the project — illustrators, scientists, mathematicians, engravers — Clark attempted to convince a young and ambitious man of letters, Nicholas Biddle (1786-1844), to come to St. Louis to write the book. Clark clearly understood that whoever edited the journals would need clarification on countless passages. It would be more convenient to have the ghostwriter across town rather than across the country, and Clark probably wanted to maintain as much control as possible of the finished product. Biddle at first declined, perhaps because he was unwilling to relocate (“My occupations necessarily confine me to Phila.”), but two weeks later, March 17, 1810, he agreed to undertake the project. Although Biddle wrote, “I think I can promise with some confidence that it shall be ready as soon as the publisher is prepared to print it,” it was not until 1811 that the manuscript was ready to go to press. A year later he reported to Clark that the original publisher had gone broke. Biddle, who was embarking on a political and financial career that would later make him the last president of the Second Bank of the United States, enlisted the help of a man named Paul Allen to complete the project and see it through the press.

What Biddle and Allen eventually published was a competent narrative of the expedition, based heavily on the journals, buttressed with several long lists of queries (dutifully answered by Clark) and the assistance of expedition member George Shannon, whom Clark dispatched to Philadelphia to provide Biddle whatever information he might need to complete the project. It appeared with former President Jefferson’s famous biographical sketch of Lewis (“of courage undaunted”) eight years after the expedition’s return. All the scientific data of the expedition was excised by Biddle, who (with Clark) expected Benjamin Smith Barton to handle that material in a related volume. Barton died in 1815 without having accomplished that extremely important task, thus costing Lewis his rightful high place in the annals of American natural science and marooning the published work as more an adventure narrative than a full Enlightenment report.

It’s not clear what Jefferson thought of the Biddle-Allen narrative. By now a long time had passed. He was no longer President. America’s second war of national independence, the War of 1812, had intervened. By 1814 Jefferson’s private world at Monticello was beginning to come apart, mostly because of his increasingly precarious financial situation. In the celebrated and voluminous correspondence between Jefferson and John Adams (1812-1826), the expedition is mentioned only once and then only to contrast the direction of the Lewis and Clark route with that proposed by John Ledyard during the Paris years. Jefferson must have known that the Biddle “travel narrative,” as Donald Jackson calls it, was a weak substitute for Lewis’ projected three-volume report, and a pale (and provincial) shadow of the kind of multi-volume publishing project that generally followed English and European explorations, including those of Captain James Cook and, more recently, Alexander von Humboldt, who had visited Jefferson in the White House in 1805.

For most of the next century, that was Lewis and Clark.

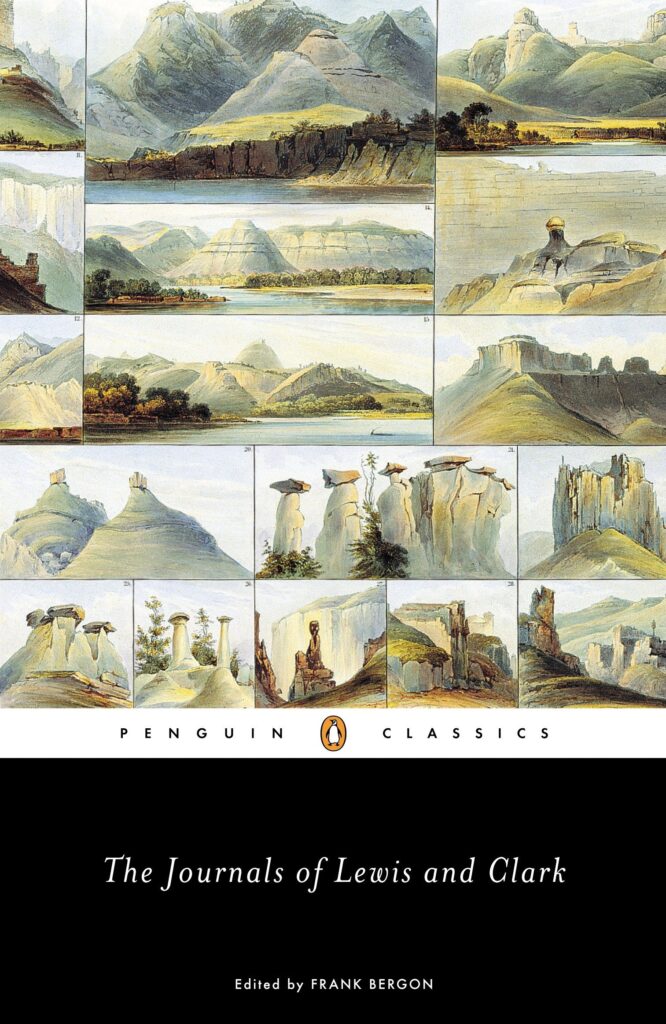

It wasn’t until the Reuben Gold Thwaites’ eight-volume Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition edition of 1905 that the public was able to read much of what the expedition members actually wrote. A dozen years earlier, another editor, Elliott Coues, who also had access to the original journals, incorporated passages into his updated, scholarly edition of Biddle-Allen, History of the Expedition Under the Command of Lewis and Clark. It wasn’t until 1953 that the first one-volume abridgement was published. This popular edition by Bernard DeVoto, outstanding western historian, editor, and conservationist was the most widely read edition of the journals available until the University of Nebraska and Gary Moulton entered the picture in the 1980s.

In what Meriwether Lewis might have called “this chapter of accidents,” we lost, and we gained. It’s a paradox at the center of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. We’d give anything to have those 23 Native American vocabularies, Lewis’ thoughts on the treelessness of the prairies, his mature recounting of every important moment of the expedition, his sense of destiny, his flights of epic prose, his anticipation of the westering movement of the nation. No one ever wished Lewis had written less.

And yet. Had he written his book(s), it is at least possible that the original journals would have been lost or discarded or buried in some subterranean vault somewhere, with the loss of their immediacy and wonderful rawness, including details that would surely have been suppressed for the sake of decorum. And, had he written his full account, with the literary formality to which he was sometimes susceptible, we might find the finished work less accessible, less delightful, and less of the fabulous adventure story we inherited. I confess that when I read the Penguin Nature Classics edition of the journals, excellently edited by Frank Bergon, I sometimes found the emphasis on natural history tedious, and long for a lost tomahawk or another screwup by Toussaint Charbonneau!

Enlightenment treatises can be tough sledding, but the Lewis and Clark Expedition as we have come to know it is one of the most compelling stories in American history.