Clay reflects on the historical dynamics of the “Ten Young Men” who made up the original core of Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery.

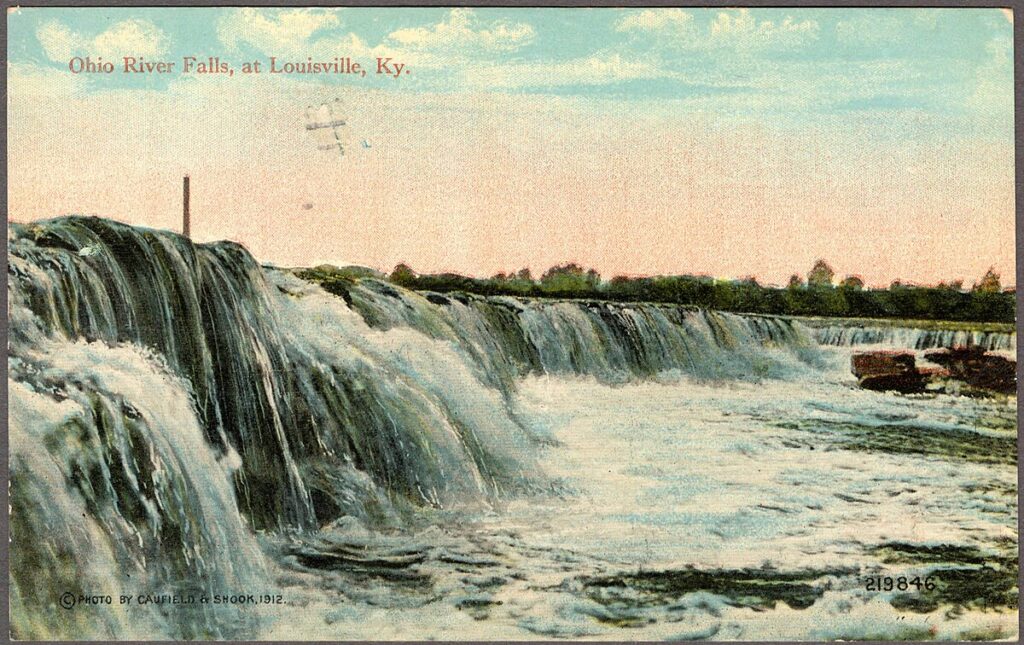

Weems, Virginia — As I gather my energies for the ongoing trek across the continent in the path of Lewis and Clark, I am reading about the mustering of the expedition’s crew. How did the two captains recruit 40-some adventurers for their journey? Congress had initially authorized 12–15 men, and Lewis had had that many 1803 Harpers Ferry rifles made for a reconnaissance party of that size. But Lewis decided he needed more men to be secure as he ascended the Missouri River through “Indian Country.” He tripled the number of participants before the expedition left St. Louis on May 14, 1804.

So where did the men come from? The answer is that we don’t know enough about this subject. They recruited men at several western army forts. They recruited French Canadian river experts in St. Louis and even a little higher on the Missouri. It’s a fascinating story, but that is not my purpose here.

William Clark recruited the core of the Corps of Discovery at the Falls of the Ohio at Louisville/Clarksville before Lewis arrived on October 15, 1803. This contingent is known historically as “The Nine Young Men from Kentucky.” John Shields, Nathaniel Pryor, William Bratton, John Colter, Joseph Field, Reubin Field, George Gibson, George Shannon, and Charles Floyd. Nine young white frontiersmen from Kentucky.

But there was a tenth young man from Kentucky, Clark’s enslaved valet York. He was about the same age as Clark, who was 33. York had been Clark’s body “servant” for most of his life. He made the entire journey from Louisville to Astoria, Oregon, and back again. On the great journey, York played a significant role. He sometimes carried a gun alone away from the boats. He helped Clark, Sacagawea, and her infant son Jean Baptiste Charbonneau survive a flash flood at the Great Falls in Montana. He impressed Native Americans, most of whom had never seen a Black man before. Some thought he had special power or even perhaps was the expedition’s leader. He did the same work as the rest of the men of the expedition and, in addition to that, waited on Clark as needed.

York was a young man from Kentucky, but does not make the traditional list of “Nine Young Men ….” This can only mean one thing. York was not counted because he was Clark’s personal property. You could easily surmise that he was omitted because white people of that time routinely regarded African Americans as less than, subordinate to, the white people around them, and having “no rights which the white man was bound to respect,” as it was later put in the notorious 1857 Dred Scott decision. Or think of Huckleberry Finn , when Huck reports a steamboat explosion on the Mississippi. The woman he is visiting asks, “Good gracious! Anybody hurt?” To which Huck replies, “No’m. Killed a n ……” To which she replies, “Well, it’s lucky; because sometimes people do get hurt.”

Isn’t it time to retire forever the concept of Nine Young Men from Kentucky and say Ten Young Men from Kentucky instead? People casually invoke “Nine Young Men” because it is an important part of the Lewis and Clark tradition. Still, even if we don’t intend it, we are perpetuating what can only be called a racist formulation. Of course, some will defend Nine Young Men and say that York, as Clark’s slave, belongs to a different category of expedition participant. By that logic, because Clark isn’t enumerated among the Nine Young Men, and York was not a volunteer on the journey, there is no particular problem in not mentioning him among the men Clark recruited (instead of ordered) to participate.

Maybe so, but I believe it is time to retire the Nine count.

A Brief Summary of Each “The Ten’s” Role in the Laws and Clark Story

John Shields was the oldest member of the Corps. He was the blacksmith, the ironworker, and the gunsmith of the expedition. Lewis singled him out as indispensable to the enterprise’s success. He was 35.

Lewis and Clark never created a list of the skill sets they needed in the men they recruited for the expedition. All Lewis said to Clark was that they wanted “some good hunters, stout, healthy, unmarried men, accustomed to the woods, and capable of bearing bodily fatigue in a pretty considerable degree.” Men with the right stuff. No gentlemen’s sons. Strong backs. Somehow, the two captains got the skill sets they needed without creating a specific job description chart. Shields the blacksmith, Gass the carpenter, Whitehouse the skin dresser, Drouillard the sign language interpreter, etc. As we look at the personnel lists from the outside, the skill set we would most want to add to the roster is artist/illustrator. That would have made a huge difference. “Yes, he can draw, but can he throw his weight against a tow line?”

Nathaniel Pryor was one of the four sergeants of the expedition. He should have kept a journal, but does not seem to have done so. He was sufficiently trusted after the expedition to be given the command of a mission to return a Mandan leader, Sheheke-shote, to the earth lodges of today’s North Dakota after Sheheke had spent time in Washington, D.C., meeting the “great father” Jefferson.

William Bratton was gravely ill at the shore of the Pacific in the winter of 1805–1806. Captain Lewis expressed real alarm about Bratton’s prospects of recovery. We are not sure, but he probably suffered from an inflamed or slipped disk in his back. He eventually recovered thanks to sweat baths used by the Nez Perce people.

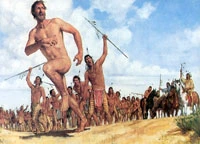

John Colter was one of the very ablest of the men. He was given special assignments from time to time. After the expedition, he became one of America’s first mountain men. In fact, he did not return to St. Louis with the expedition. At his request, the captains released him in today’s North Dakota to go back upriver with a couple of rookie beaver trappers they encountered. Two years later, “John Colter’s Run for Life” near the Three Forks of the Missouri after angry Blackfeet Natives stripped him naked and gave him a head start, is one of the greatest legends of the Old West.

Joseph and Reubin Field. Young brothers are among Meriwether Lewis’s favorites. They were fast runners, temperamentally even and reliable, and excellent hunters.

George Gibson is best known as the second violist of the Corps of Discovery. The half-blind Pierre Cruzatte was the principal musician, but Gibson brought his fiddle too. He knew a fair amount of the Native sign language. He also suffered one of the most grievous wounds of the crew when, on July 18, 1806, he fell on a tree snag that penetrated two inches into his thigh. In an age before antibiotics, that was a severe injury.

George Shannon was the youngest member of the expedition at 18. He got lost seriously once (in today’s South Dakota: 16 days) and in a lesser way later in southwestern Montana. The author of a medical history of the expedition concluded that Shannon needed a prescription for Ritalin. This has always bothered me, and I suggest to the author that he spend 28 months in the wilderness, often away from the main party, and never get lost or bewildered. I’m always amazed that no more men were lost at one time or another. The idea, as the great historian James Ronda puts it, is that we have locked each member of the expedition into a few stereotypical epithets, based on meager details drawn from the hundreds of thousands of words in the journals, and that poor Shannon is now known as “Shannon the forever lost.” This undoubtedly distorts the record. The details that wind up in the journals were not meant to be comprehensive and representative. Lost one day, great hunter the next. It would be like saying George Herbert Walker Bush is the “man who threw up at a Japanese state dinner.” He did, but does that tell us what we need to know of the 41st president of the United States?

Charles Floyd was the first expedition member to die. He became suddenly ill in mid-August 1804 near today’s Sioux City, Iowa, and died at age 22 on August 20 of what the captains (not knowing what had happened) called “bilious fever.” Floyd seems to have been a special favorite of William Clark. He was attended in his brief last illness by Clark’s enslaved valet York.

The Tenth Young Man From Kentucky – York

York has only one name by which he is known to history. He performed admirably on the expedition and out west, beyond the physical and moral boundaries of “civilization.” He was often treated like a full and perhaps even equal participant in the adventure. Frontier dynamics often broke down tightly regimented social categories typical back in places like Williamsburg or London. When the expedition returned to St. Louis, York seems to have asserted himself with his master Clark, expecting to be freed altogether or at least granted special status after all that he had contributed to his master’s and the expedition’s success. But the minute Clark returned to “civilization,” he plunged York back into his status as chattel. York wanted to live with his wife and children at the Falls of the Ohio; Clark insisted that York accompany him (alone) to St. Louis. Clark’s treatment of York was so selfish and cruel that what we now know about this post-expedition relationship has significantly damaged Clark’s historical reputation. At one point, after Clark threatened to sell York into the Deep South, it was Meriwether Lewis who intervened and convinced Clark not to do so horrific a thing. Whether Clark formally freed York is uncertain, but he later permitted him to establish a trucking business at the Falls of the Ohio.

Such were the Ten Young Men from Kentucky. They may have been the core of the Corps of Discovery, but they were not necessarily better at their work than other participants. The captains had special regard for several other men: Patrick Gass, the expedition’s carpenter, who seems to have superintended the construction of Fort Mandan and Fort Clatsop; Joseph Whitehouse, the skin dresser who helped the men fashion clothing and moccasins from deerskin after their cloth clothing played out; and above all George Drouillard, who was their master hunter, trailsman, and sign language interpreter.

Most members of the Lewis and Clark expedition appear on history’s stage suddenly — out of nowhere — and after their service on America’s most extraordinary exploration mission (1804–1806) disappear again into oblivion. A superb scholar named Larry Morris has undergone painstaking research to find what little can be said of every member of the crew before and after the expedition, but for most there is not much to report: perhaps a birth date, maybe a death date, perhaps one or two more details. About half of the expedition’s crew rarely get mentioned in the journals. That does not in any way diminish their contributions. Unfortunately, no expedition member ever stopped to describe the personnel in detail, including the Shoshone-Hidatsa woman Sacagawea, one of the two most famous Native women in American history. The captains didn’t know we would be fascinated, so they didn’t provide character sketches.

It’s too bad that the 30-some men didn’t each get a book contract when they returned, didn’t develop a website, and didn’t star in a documentary film about their pivotal role in the expedition’s success. We have what we have in what amounts to a thin biographical record, and we are forced, no matter what James Ronda warns us to avoid, to lock the men into whatever descriptive tidbit we have, whether it is representative or not. Shannon the forever lost.

Besides the captains, York, and of course Sacagawea, John Colter is the best-remembered member of the Corps of Discovery. It never hurts to streak across the cactus plains of western Montana.