Christopher Nolan’s acclaimed new film has ignited a fascination with Robert Oppenheimer. As a historian who has studied the life of the noted physicist and American presidents, Clay reflects on a surprising connection between Oppenheimer, John F. Kennedy, and “America’s da Vinci,” Thomas Jefferson.

Director Christopher Nolan’s summer film sensation has me thinking about a delightful connection between three amazing Americans: Robert Oppenheimer, John F. Kennedy and Thomas Jefferson.

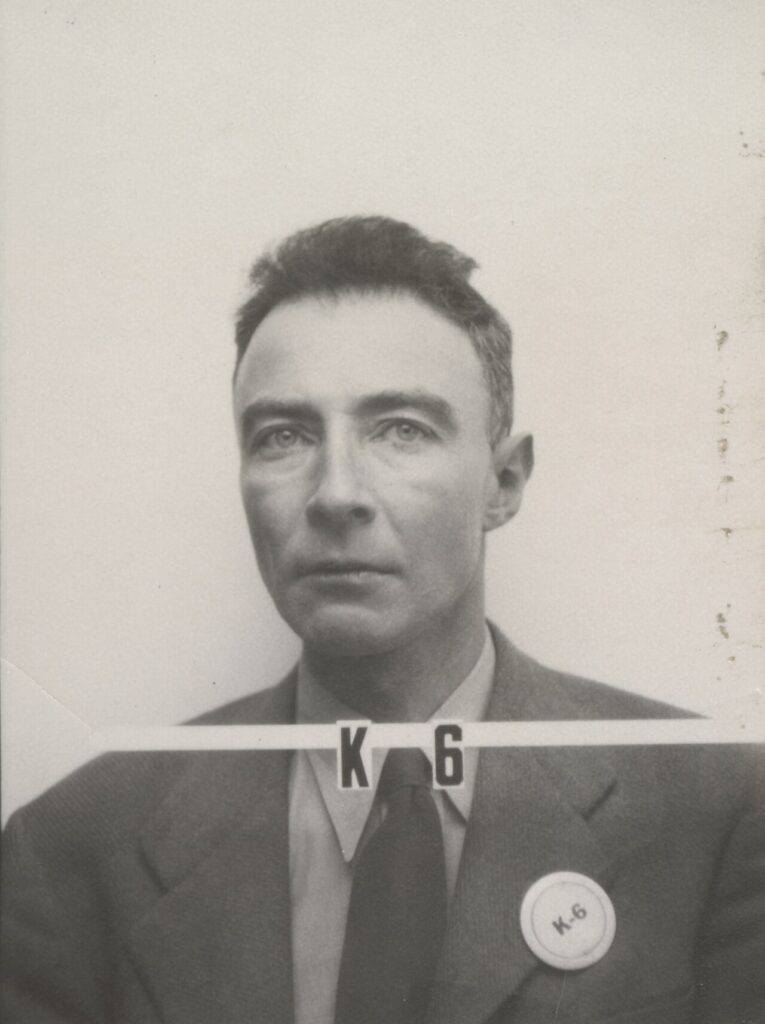

But first, to review: Oppenheimer built the atomic bomb. He became the most prominent scientist in the United States. He had doubts about the ethics of a hydrogen bomb. The hardliners of the Cold War wanted him silenced. His security clearance was stripped and he endured a humiliating security “hearing” in the spring of 1954, which more resembled a Soviet show trial. After his fall, he retreated to the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton. Over time, and particularly with the election of John F. Kennedy, Oppenheimer was carefully rehabilitated in the national arena.

Oppenheimer was a genius. A highly complex man. A searching humanist. A student of other cultures and languages. An arrogant man who did not suffer fools. He had spent time with American members of the Communist Party in his early Berkeley years. He was not fastidious enough about his contacts with radicals who were his friends during and after the Manhattan Project.

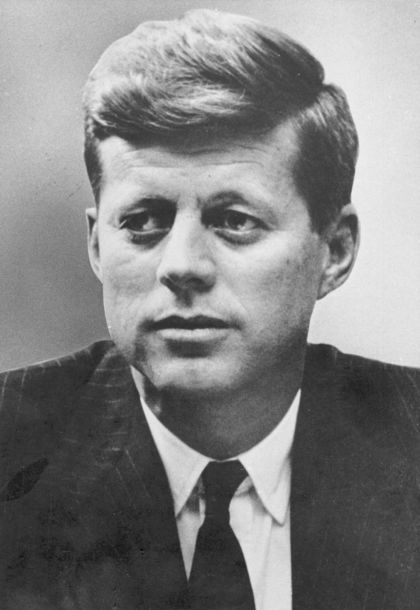

As 1960 unfolded, a Massachusetts senator named John F. Kennedy sought the presidency. He was a political doppelganger to Oppenheimer in some ways. They both loved to read, and only some of what they read was instrumental to their career paths. They loved a good cocktail. They sometimes gravitated toward women who were not their wives. They both loved to talk about geopolitics and were obsessed with the threat of nuclear war. They both had excellent wit, a lively sense of irony, and a winning habit of self-deprecation.

Kennedy was cautious about rehabilitating Oppenheimer. He was a serious Cold Warrior, and periodically belittled by the hawks and hardliners among the American security community, JFK had to exhibit considerable bravado about national security issues. He wanted to do what he could for Oppenheimer but did not want to detonate a costly political backlash from that part of America that believed he was too young and urbane to be tough enough to lead the nation.

So, as a political trial balloon, Kennedy invited Oppenheimer to a state dinner for America’s Nobel Prize winners on April 29, 1962. Oppenheimer never won the Nobel Prize but knew many of the 49 men in the room. In addition, Oppenheimer mingled that night with John Glenn, Robert Frost, the widow of Ernest Hemingway, Pearl Buck, George C. Marshall, and other national luminaries.

That’s when Kennedy made his famous tribute to Thomas Jefferson: he called the evening “the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.”

Drop the mic.

“I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.”

President John F. Kennedy, April 29, 1962

Jefferson was the only president about whom that wild compliment could be spoken. It might be more strictly accurate if it were John Quincy Adams or Theodore Roosevelt dining alone, but Thomas Jefferson was America’s da Vinci, the closest we have had to a universal scholar. Kennedy’s bon mot would have been less powerful and delightful if it had not been Jefferson.

When I perform as Jefferson, afterward, some man (always a male) comes up and says, “I don’t know if you have ever heard this, but John F. Kennedy was hosting a group of [this varies with the telling], and he said …

I usually respond to this the same way. “Well, it’s of course, a logically nonsensical thing for JFK to say even with qualifying disclaimer, ‘possible exception.’ These were 49 of the smartest men in America, any one of whom probably had more brain power than Jefferson, the enlightened amateur.” And then I say, “Besides, when did Jefferson ever dine alone?”

Oppenheimer was there that night! What would Jefferson and Oppenheimer have talked about if they had met? How would Jefferson react to the limits of Newtonian mechanics? How would he react when Oppenheimer told him that light is both a wave and a particle and that you cannot cling to either definition and understand the universe? What would Jefferson have said about Schrödinger’s Cat? Maybe his head would have exploded like the computers in early Star Trek episodes. What would a Black Hole mean to someone who disbelieved in extinction and reckoned boldly that the universe might be as many as 60,000 years old?

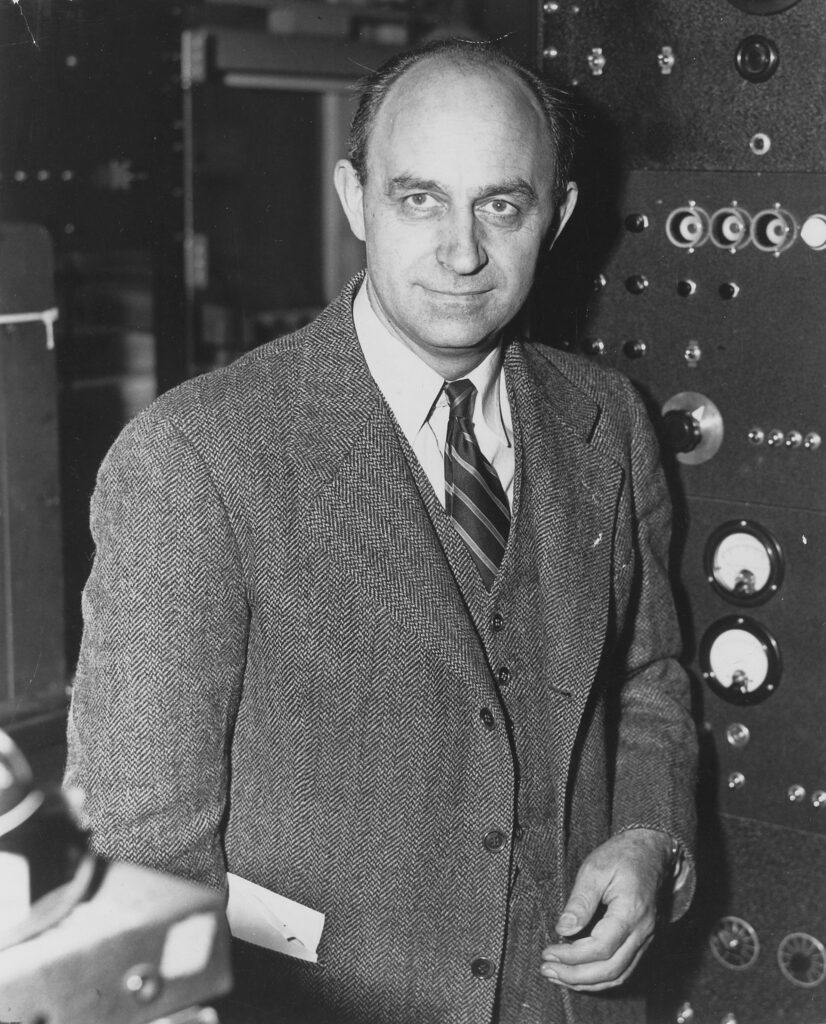

The Kennedy-Oppenheimer story doesn’t end there, however. In 1963 the Kennedy administration, now with the willing cooperation of the Atomic Energy Commission, decided to award Oppenheimer the highest honor reserved for a physicist in America, the Enrico Fermi Award. This was a more courageous and dramatic rehabilitation of Oppenheimer. The award would signify that our long national nightmare of McCarthyism and the black-listing of intellectuals and Hollywood actors had ended.

The award was to be presented to Oppenheimer in a White House ceremony on Monday, December 2, 1963.

And it was.

But we all know what happened. …

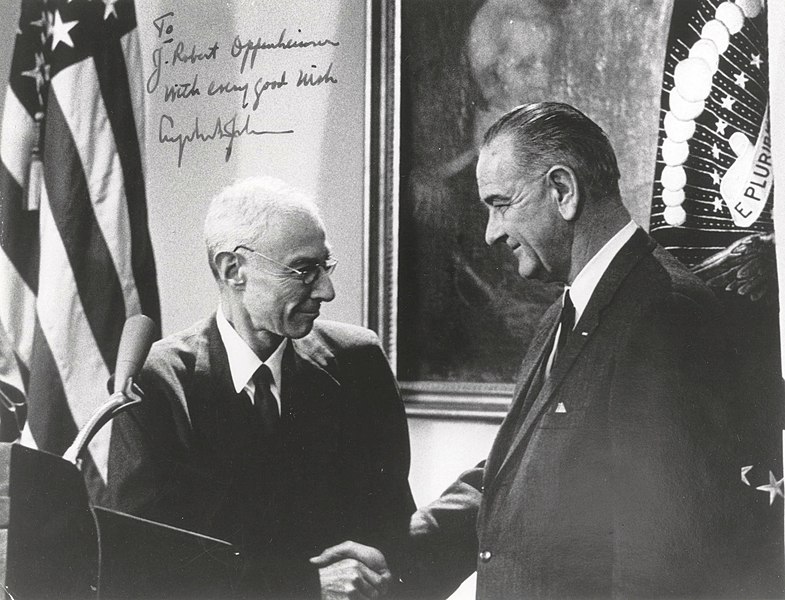

In the wake of the assassination, the new president, Lyndon Johnson, decided to proceed with the award ceremony as planned. December 2, 1963, was 21 years to the day after Enrico Fermi’s atomic pile went critical under Staggs Field at the University of Chicago. Great though the award ceremony was for Robert Oppenheimer, he must have been grieving as much as celebrating when the president presented him the Fermi medal, and of course LBJ was no JFK. To have received that medal from the hands of John Kennedy would have been one of the supreme moments of Oppenheimer’s life. With unusual grace, LBJ said giving Oppenheimer the coveted award was “one of President Kennedy’s most important acts.”

In his brief acceptance remarks — it would be wrong to call it a speech — Oppenheimer closed the loop with Thomas Jefferson. He said that President Jefferson “often wrote of the brotherly spirit of science. … It is in part because, with countless other men and women, we are engaged in this great enterprise of our time, testing whether men can both preserve and enlarge life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and live without war as the great arbiter of history.”

As he prepared his remarks before the event, perhaps Oppenheimer remembered JFK’s Nobel laureate quip about Jefferson dining alone with his self-contained genius. Maybe not. Then Oppenheimer turned to Johnson himself and said: “I think it is just possible, Mr. President, that it has taken some charity and some courage for you to make this award today. That would seem to me a good augury for all our futures.”

Augury is a curious word for a scientist to utter. Augury hearkens back to the ancient world when priests studied the entrails of animals to advise Rome’s leaders about great public decisions and acts. But then Robert Oppenheimer was no typical scientist. He learned Italian to read Dante and Sanskrit to read the Hindu sacred texts, including the Bhagavad Gita, which lifted him into immortality with the phrase, “I am become Death, the Shatterer of Worlds.”

I saw John Kennedy’s famous Jefferson witticism on the actual document from the Nobel Prize dinner. It was on public display decades later at the National Archives. What made it so fabulous is that the speech originally had some much less interesting introduction. In his own handwriting, it was Kennedy himself who wrote in the margin of his copy the glorious trope of Jefferson alone in the White House a couple of hundred years earlier.

It made the hair on my arm stand up.

If the super-sophisticated JFK had lived to present the award and then perhaps had invited Dr. Oppenheimer back to the private quarters of the White House to share a martini or two, imagine what sort of conversation these two highly literate intellectuals would have shared.