My friend Dennis McKenna and I had the good fortune to experience the solar eclipse of 2024 at Chaco Canyon in northwestern New Mexico. We hired a Native guide to take us around the site and interpret its spiritual significance. When we arrived at the Chaco Canyon Visitors Center parking lot mid-morning on April 8, our host handed us each a pair of solar eclipse goggles. There were six of us altogether: our interpreter, Kialo Winters, and his wife, Terri, an older couple from Colorado Springs celebrating their 58th wedding anniversary and the two of us.

Kialo answered a preliminary question with exceptional grace. A woman in our group asked him how we should identify him. We’ve heard it all, he noted, but we prefer to be called by the tribe we belong to: Zia, Navajo, Hopi, Lakota, Ojibwe. “But if you don’t know, please don’t say Native American. We’re not Americans in the usual sense. We’re a separate sovereign people.” He did not elaborate, but it was clear that he wanted to distinguish between the varieties of Americans (Irish Americans, Italian Americans, Polish Americans) and his own distinct nation (they were here first, of course). He said if you must choose a generic name, “Indigenous is best.” He said these words in so generous a way that not even a cultural conservative could be offended.

Kialo Winters is Zia and Navajo. His wife, Terri, is Navajo. When they met, he knew almost no Navajo. She grew up in a more traditional family and had almost no English. They have been teaching each other fluency ever since.

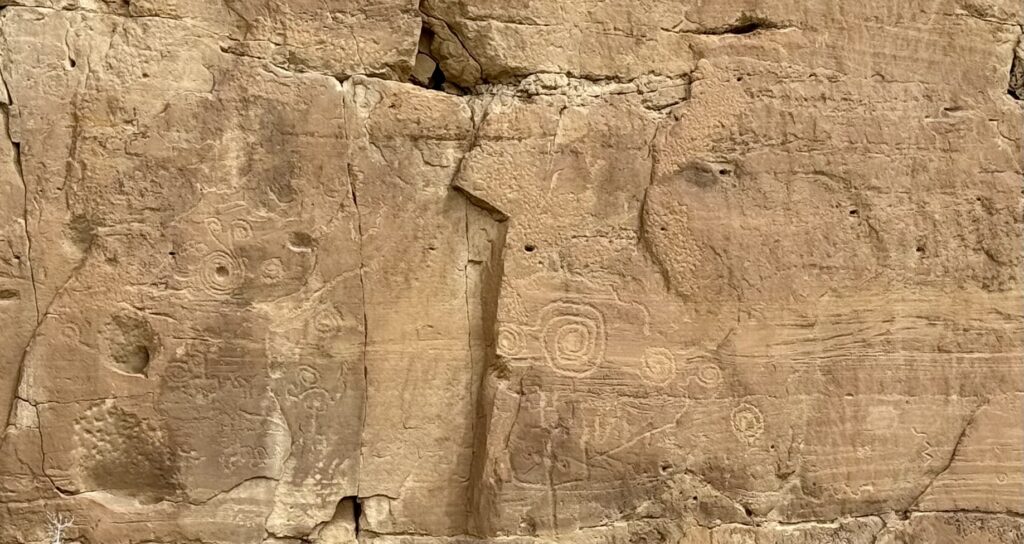

We moved slowly through the site, stopping to peer up at the sun every few minutes. Those who know and love Chaco Canyon say we should not use the word “ruins,” as in the “ruins of ancient Troy,” because the descendants of the people who lived here a thousand years ago still use the site for a range of purposes, including the seasonal calendric wisdom that it embodies.

The surviving walls of the village complex are amazingly orderly, intricate, and intact. Because it is an essentially treeless landscape, the timbers needed for the tall apartment complexes had to be cut in the mountains 60 miles away and carried in a sacred manner to the village site. Not only was there no Home Depot in the ancient Puebloan world, but the idea of warehousing lumber without any special concern for the place of its origin or the spirit of place of its origin was anathema to these people. We were observing what is left of an entirely different worldview.

I’ve visited ancient Troy, Mycenae, and Roman villas, including Pompeii; Chaco’s surviving structures are far more neatly constructed. On any given stretch of wall, the shales had been cut and shaped into slender “bricks” that were woven together with painstaking care and precision. These were very sophisticated architects with low-tech tools that would flummox a modern construction engineer.

Paradigm Shift

Total solar eclipses don’t happen very often. In the last couple of decades, in a media-saturated world, they have become lucrative tourism opportunities under the terms of late capitalism. More people observed Monday’s eclipse than any other celestial event in human history. Thomas Jefferson or Captain James Cook would have given anything to have a single “photograph” of a celestial event of their times. On April 8, 2024, hundreds of millions of photographs were taken worldwide, all of the same thing! Some media entities had the good sense to ask people to share their photographs publicly. We live in a wondrous time.

I have a friend who lives in Fort Collins, Colorado, who flew to Dallas Tuesday morning solely to see the eclipse in totality. He landed at Dallas Fort Worth International, took an airport bus to a high-rise parking garage, joined a few scores of other people on the open-air top lot, pulled out his goggles, observed the eclipse, got on the bus for the terminal, and flew home. He left his house in Fort Collins at 5 a.m., spent 4.3 hours in Dallas, and was back in his house at 6:45 p.m. This Total Eclipse Insertion Project (TEIP) cost him about $700. Such a journey is a monument to the fabulous wealth of the United States in the 21st century. At least he did not join one of those charter flights that tracked the eclipse across its long arc over the North American continent. Captain James Cook was sent to observe the transit of Venus on the island of Tahiti in 1769. He was gone for three years.

I have another friend in Washington state who is fascinated by such celestial phenomena, but he was content to watch the eclipse on CBC television. Yet another friend paid a small fortune to participate in a guided Eclipse Tour in south Texas — he flew in from Seattle — only to be half-stymied by heavy cloud cover.

Until now, I have regarded eclipses and transits in Enlightenment (Jeffersonian) terms as those rare moments when the heavenly curtain is parted, and we get to see the clocklike workings of the solar system. The philosophers of the Enlightenment believed that the universe had been created by a Clockmaker God, who employed gravitation and Newtonian mechanics to spin the solar system. On any given day, we might be disposed to take the order of the cosmos for granted — the sun “comes up,” there is high noon, and the sun “goes down,” and the stars “come out.” An eclipse pulls us out of our complacency and invites us to think more seriously about celestial mechanics. It’s one thing to observe an eclipse and to be filled with wonder at the idea that the moon is poised precisely where it occludes the entire sun for a few moments. It makes you want to make your way to the nearest planetarium.

I remember walking through the Enlightenment Room of the British Museum a dozen years ago, ambling past scores of telescopes, astrolabes, sextants, octants, artificial horizons, maps, and illustrated journals, and then seeing a glass dome on my left, 4 feet in diameter, encasing an elaborate mechanical apparatus. I was nearly past it when I did a literal double-take because I recognized it as an orrery, dating to 1750, a brass and ceramic model of the solar system, named for one of the design’s patrons, Charles Boyle (1674-1731), the Fourth Earl of Orrery. I nearly swooned. I spent the next half hour gazing at its mechanical magnificence, the yellow sun at the center, each of the planets on a separate stiff wire — Mercury, Venus, the Earth with its lovely ivory moon, Mars, Jupiter (including its Galilean moons), and Saturn with its gossamer rings. The British Museum no longer operates this ingenious and intricate machine, but it was designed to recreate the actual motions of the solar system, and in the beginning, it could be cranked into clocklike motion as exquisite as the fabled “Music of the Spheres.” If you are rich enough to fly to Dallas to observe an eclipse, you can probably afford one of the modern recreations of the orrery. If I had the money, I would purchase my own orrery for my map room at home. I am sure I would be more rational for having and operating it.

This eclipse was different, and it knocked me right out of the Enlightenment paradigm. This time, I was in a sacred place, far from the madding crowd at Niagara or Mazatlán. We six were virtually alone in one of the most beautiful landscapes in North America. We were in an architectural complex designed as a shale and mortar orrery by a pre-industrial people we Americans would formerly have been disposed to call “Indians.” We were in a sacred place, guests of a Zia and Navajo man who talked about the site’s wonders and mysteries in an understated manner — British Museum orrery 1750; Chaco Canyon complex circa 900 CE (AD).

Kialo told us the ancient Puebloans employed a person as the nation’s Skywatcher. His duty was to study the heavens. Not to compare the sublime with the pedestrian, but he was their Carl Sagan or Neil deGrasse Tyson. His job was to discern the order of celestial phenomena, find a way to memorize the data, and advise his community about when to plant, harvest, hold the sacred festivals, and pray to the Great Mystery who spun and regulated the solar system. How did they do it? European civilization has been able to predict the solar eclipse since May 28, 585 BCE, when Thales of Miletus exhibited his astronomical and mathematical mastery of the Greek world, but indigenous celestial knowledge almost certainly predates Thales by thousands of years.

Industrial civilization has created an enormous amount of light pollution. Even in my lightly populated North Dakota, there is enough urban light to make it impossible to observe the night sky without driving 20 or 30 miles from home, a disincentive. I tried to imagine skywatching at Chaco Canyon a thousand years ago, but our guide said it is essentially the same now.

As we edged along the cliff face, we saw two falcons, one adult, one a fledgling learning to fly — with some gentle parental bullying from its mother. Poised on rock ledges 20 feet up and about 20 feet apart, they talked back and forth with a high “skree” sound, which reminded me of teaching my daughter to ride a bicycle when she was seven (and, of course, I broke my vow “not to let go”). Meanwhile, in the canyon, the largest ravens I ever saw performed some show-offy maneuvers above and around us.

After a few hours, we stopped at a picnic table and pergola for lunch. Each party brought its own repast, but there was some sharing, too. Our hosts spread a beautiful yellow patterned tablecloth over the park service beige fiberglass table.

The Eclipse in the Canyon

We could not have chosen a better place to observe the eclipse. Chaco Canyon is more than just another example of what used to be called Anasazi sites. It was designed from the beginning to serve as a lunar and solar “clock.” It was laid out with almost unimaginable ingenuity and scientific acumen so that shafts of light pass through portals precisely on the occasions of the solstices and the equinoxes even now.

It’s hard not to be overwhelmed with admiration. Here was a people without telescopes, written language, the kind of sophisticated numerical system we inherited from the Arabic world, or advanced computing devices, who knew the cosmos so well that they could track the sun and moon with massive stone works in the middle of the desert Southwest to form a calendric device as accurate as anything that could be built today. And they passed on that painstakingly gleaned understanding of the ways of the sun, moon, planets, and stars through a tenacious oral tradition. When the Puebloan people were constructing the kivas and other structures at Chaco Canyon, Europeans were still caught in an epoch so dark that they had forgotten much of the classical inheritance and jettisoned whole swaths of ancient knowledge, beauty, history, and culture in the name of a crabbed Christian (veil of tears) vision of life on earth.

Here’s to “Druidic” knowledge all over the world!

It should humble any Euro-Westerner to realize the sophistication of other cultures we for hundreds of years called primitive or even savage and blithely determined that it was our God-given mission to force them to conform to our software and discard their own. At the boarding schools, we used a wide range of psychological and physical coercion to force them out of their indigeneity and into a semi-permanent peonage in our preferred ways and means.

Being Present

“In any weather, at any hour of the day or night, I have been anxious to improve the nick of time, and notch it on my stick too; to stand on the meeting of two eternities, the past and future, which is precisely the present moment; to toe that line.”

Henry David Thoreau

Sometimes, I lagged behind the others to listen to the solitude. The great challenge of the life of adventure is to be present wherever you happen to find yourself. This is much harder to do than we think.

Henry David Thoreau put it perfectly in Walden: “In any weather, at any hour of the day or night, I have been anxious to improve the nick of time, and notch it on my stick too; to stand on the meeting of two eternities, the past and future, which is precisely the present moment; to toe that line.” When I am in a special place — high up in the Bitterroot Mountains on a perfect August afternoon, canoeing the White Cliffs section of the Missouri River east of Fort Benton, Montana, or in the Pantheon at Rome or Sainte-Chapelle in Paris — I try to do some deep breathing. I will myself to open every pore of my consciousness so that I can really “drink in” the moment, to remember the quality of the light, the temperature, the wondrousness of the landscape, the intricacy of the stained glass windows, and the mysterious stories they tell. To use a contemporary metaphor, I try to etch the experience on the hard drive of my mind so that my impressions are not just observational ephemera that get dumped with the rest of the data that find their way through our senses into our brains. I often experience a kind of tragic feeling as I stand before Stonehenge or the Grand Canyon, that I am not taking it deep enough, that I am not letting it all the way in, that I am not alert on Thoreau’s meeting point of the past and the future. As I sit gazing at Michelangelo’s David in Florence, I strain to let the experience take over my whole being for a time. I think we all have this feeling at times.

There was no totality in Chaco Canyon. We got four-fifths occlusion but no more. I was fortunate enough to observe the 2017 eclipse in central Wyoming, where I had my only experience of totality. There is a dramatic difference between 80 and 100% occlusion. But in 2017, I was on a gravel ranch road north of Casper, Wyoming, sitting with my back to a barbed wire fence. That was a magical experience, but I certainly wasn’t in a sacred landscape. Central Wyoming was a landscape that has been occupied for the last 120 years by Anglo-Americans to raise alfalfa and beef. The roads have been laid out according to the rectangular survey grid system. The barbed wire is the miracle invention that made places like Wyoming habitable to white people.

At Chaco, though the eclipse was less dramatic, I knew I was tiptoeing around a sacred landscape, and that somehow made it a much more meaningful experience, especially with an Indigenous couple to teach us how to see it. We kept our voices low. There was no joking around.

At the end of the tour, we were taken to the great kiva, Casa Rinconada, a place of beauty, silence, and delicacy. From there, we could look south and east at a vast and dramatic landscape of cliffs and buttes. Kialo told us that kiva Chaco people could see the exact notch where the sun rises at the spring and autumn equinoxes and the solstices. It was one of the most beautiful viewsheds I have ever seen. I felt a serenity almost impossible to achieve in modern American culture. These were people who lived under the sky. We mostly live under our roofs.

We were sorry to say goodbye to our hosts. In the late afternoon, Dennis and I drove back to Farmington, N.M., a city of 47,000. We were unusually quiet, both of us, as we left the site. What a privilege to live in this great country where people with fundamentally different approaches to life are available for those who wish to learn from them.