Cooperstown, New York — When I bought my ticket Saturday afternoon at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the clerk asked for my zip code — 58503. “Huh,” he said, “isn’t that where Roger Maris comes from?” I was about to say yes when a free-floating usher who had been standing 10 feet away jumped into my personal space and shouted, like a contestant on Jeopardy, “Fargo, but he’s not in here.” I pulled back a bit, shocked by the intensity of passion that this game generates, and asked why not. The interrupter looked at me with derision. “His stats just aren’t there. It was a one-off, and it doesn’t really count because there were more games in 1961 when he hit 61 homers. It’s still the Babe, man. Maris was great, but he doesn’t belong in the Hall.” The original clerk asked me who other great North Dakota Major League Baseball players were. I shrank away in shame.

It was going to be that sort of afternoon.

Among great baseball players not in the Hall of Fame: Mark McGwire (performance enhancement drugs, PED); Barry Bonds (PED); Sammy Sosa (PED); Roger Clemens (PED); Curt Schilling (what are regarded as “character issues”); Alex Rodriguez (PED); Rafael Palmeiro (PED).

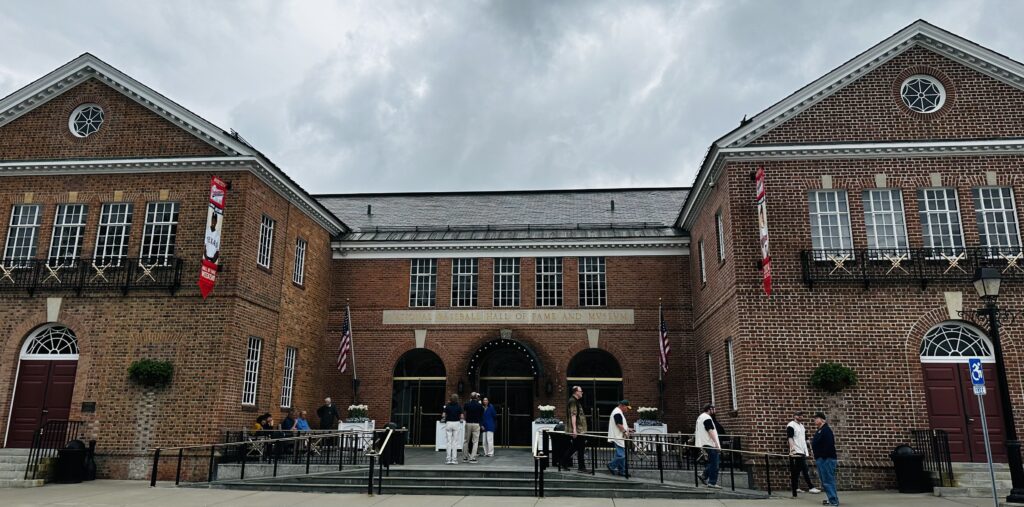

I don’t know what I expected when I drove my Airstream into Cooperstown, New York. Having never really thought about it before (it is my first, but not my last, hall of fame), I had reckoned that Cooperstown would be a city of about 75,000 and the Hall of Fame would be a gleaming aluminum and glass one-story structure built or rebuilt in the 1990s. Turns out Cooperstown has fewer than 2,000 permanent residents. The Hall of Fame building was dedicated in 1939. It was constructed with rose-colored atom bricks (slightly smaller than typical) with a central three-story tower and two wings, right on Main Street, and without the acres of parking I had expected.

Cooperstown is a lovely village, exceedingly tidy and well-groomed. It has Victorian gingerbread houses and brick buildings everywhere on Main Street, about three blocks long. Virtually every building houses a sports paraphernalia shop or a sports-themed restaurant. My friend Russ, who has been there four times, says there are several outstanding restaurants in Cooperstown. These are the kinds of things he knows.

Big History in the Hall of Fame

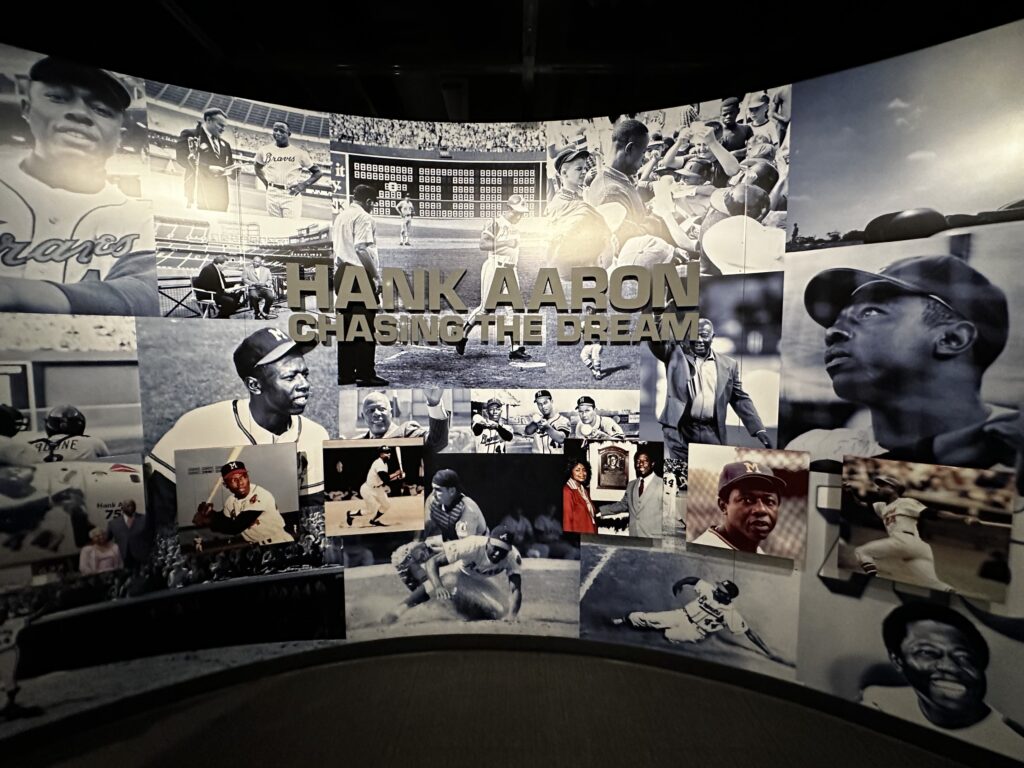

I suppose 200 people were working their way through the three floors of the Hall of Fame. It was very moving to see fathers with their wide-eyed 9–12-year-old sons high-tailing it from display to display, with the fathers explaining baseball history to their sons or their sons to their fathers. Seeing African Americans standing at attention before the panels dedicated to Hank Aaron and Jackie Robinson was equally moving. Jackie Robinson, who broke the color barrier in the Majors in 1947, is as important in the history of Civil Rights in America as Rosa Parks or James Meredith. Hank Aaron received vicious death threats couched in the vilest of racist language as he approached the home run record in 1973 and 1974. What’s the proper chorus for this sad fact of American life: “God shed his grace on thee?” or “A hard rain’s gonna fall?” Aaron hit his 715th HR on April 8, 1974 (Ruth topped out at 714 on May 25, 1935). Aaron ended his career at 755 in 1976.

Barry Bonds hit 762 home runs altogether, but in the minds of many, that doesn’t count since he was boosted by performing enhancing drugs.

A Black woman in a wheelchair sat quietly before a monument to Jackie Robinson, wiping away her tears.

Some of the white males who were visiting the Hall of Fame looked like overgrown boys locked in the last days of pre-adolescence. They were almost all alone. They were all dressed alike: shorts, a player jersey untucked, and a ball cap. They had all put on some poundage since their prime, and none of them seemed to have taken any exercise for a decade or more. I was surprised some of them weren’t wearing their old sandlot glove. They were there to worship and to re-fantasize their boyhood dreams.

Sports addicts are passionate people. Every few minutes, I happened upon two or three men having mostly friendly arguments about baseball stats and debating who was the greatest third basemen in the sport’s history, who is “terribly overrated,” who “changed the game,” and who would absolutely have been inducted if he hadn’t used steroids: “and he didn’t need to, for God’s sake, he was that good without any help from big pharma.” I’m glad to report that I didn’t hear a single argument over Pete Rose, one of the greatest players of all time: 4,256 hits (most of anyone), most at-bats, most games played, most singles. He won three batting titles, one MVP Award, two Gold Gloves, and was Rookie of the Year in 1963. But he gambled. He gambled on his own games. He’s barred from the Hall of Fame, but he mounts a campaign to be reconsidered every five years or so. He’s 83 years old now, and that was a very long time ago. Now that gambling has become an integral element of major league sports, I say put him in while he is still alive to take some late-life satisfaction. Still, you can get into a sports bar fight over this almost anywhere in America. The title of Rose’s autobiography, My Prison Without Bars, tells you what you need to know about his ordeal.

One of the two vertical “decision kiosks” asks you to “vote” about Rose. Results so far? 44% say “Those Games Are Tainted,” but 56% say “Gambling’s Impact is Overrated.”

Speaking of Roger Maris, for a short time, I listened in as a tall, thin man of about 70 threw a fit over the absence of Maris on the Hall of Fame list. He sputtered. He gesticulated wildly. He shouted in a low-key way. He said, “You watch, I’m going to go down there and demand to speak to someone in charge. This is an outrage. You wait; this will not stand. This is NOT ok.” His long-suffering wife nodded in the official spouse’s “yes, but calm down already” manner. He was virtually foaming at the mouth. I wanted to ask if he were a North Dakotan, but I reckoned it was better to move to another room.

Most of the girlfriends and wives were there because their men wanted to be there, and some seemed genuinely interested, but a few of them were super-fans, the kind who out-fan their men, scream at the television when the umpires make bad calls, and high five anyone in sight when things go well. Men outnumbered women 10 to one in the building.

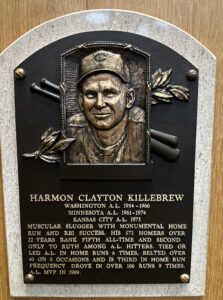

In the formal hall (of fame), I found the Minnesota Twins’ Harmon (“Harmless,” my grandfather called him) Killebrew in the 1988 class, Tony Oliva (2022), Jim “Kitty” Kaat (2022), and Rod Carew (1991). I suppose everyone who visits the Hall of Fame has a short list of must-see plaques and tributes.

Three or four times in the afternoon, I got choked up and burst into tears. Some of this is lost youth, and some of it is lost innocence. Once the asterisk started to attach itself in the record books to the careers of great players — think Barry Bonds or, in bicycling, Lance Armstrong — and Major League Baseball became yet another expression of the corrosive power of television on everything it touches, I quietly turned away. I haven’t watched the All-Star Game since 2002, when the game was called after 11 innings because neither team had any pitchers left in the bullpen. I’ll watch a bit of the fall playoffs depending on what else is going on in my life, and almost always a couple of games of the World Series if one of “my teams” is involved: the Dodgers, the Yankees, the Red Sox, the Cubs, the Mets, or the hapless Twins. But if it is Astros-Diamondbacks, I’ll watch a couple of innings and move on. The Astros’ 5′ 6″ Jose Altuve, with his Pete Rose zeal and his 5 o’clock shadow (maybe it’s seven o’clock), bugs me for some irrational reason.

The Greatest Moments in Baseball

At a special screen with a menu of the greatest moments in baseball, I watched Hank Aaron hit his 715th home run, and Ken Griffey, Jr. hit a home run on his first Major League at-bat. I watched a ball bounce off of Jose Canseco’s head (I think the correct technical term is noggin) and over the outfield wall (home run), which is even more delightful when you see Canseco giggling in the aftermath. Perhaps he regarded it as a standing rule double.

Twice, I watched a clip of Kirk Gibson’s walk-off home run in the 1988 World Series. Weird, isn’t it? I remember where I was when JFK was assassinated, where I was when the Challenger blew up, and where I was on 9/11, which makes perfect sense. Still, I also remember the evening when Gibson blew the minds of 55,983 fans at Dodger Stadium on October 15, 1988. I was living in Claremont, California, at the time. I had invited my English department friends Ray Frazer, Bob Mezey, and Brian Stonehill over to my small house to watch the game. Mezey was a fierce Dodgers fan. He had taken me to several home games that year. We chose my house because I had the best TV — an old color console set with a large picture tube. I made hot dogs for the occasion with all the fixings — plenty of beer. Bob liked only basic beer: Schlitz, Hamms, Grain Belt. We turned the sound off and listened to the immortal Vin Scully call the game on the radio. By the end of the ninth inning, with the A’s ahead 3:2, Mezey, who was something of a pessimist, reckoning that the game was over and the Dodgers would surely lose, was beginning to collect his things to go.

Then, one of the greatest moments, not just in baseball but in all of sports history, occurred. The Dodgers’ slugger Kirk Gibson was called in with two outs in the bottom of the ninth to pinch hit. He was in a severely injured state. As Scully put it, “he has two bad legs, a bad left hamstring, and a swollen right knee.” No one expected Gibson to play that night. Scully said Gibson was “so banged up he was not introduced, did not come out on the field before the game.” Scully’s sidekick, Jack Buck, said, “he almost has to talk to his legs to get anything out of them.” The crowd went wild when he came out of the dugout, though that ovation was nothing compared to what happened next.

It was game one of what turned out to be a five-game series.

Gibson’s at-bat went on for more than seven minutes. It unfolded like Shakespearean drama or the second iteration of Ernest Lawrence Thayer’s 1888 Casey at the Bat. If Hollywood had scripted the episode it could not have been finer. It was a perfect narrative as well as a perfect sports moment. Oakland’s Dennis Eckersley was one of the best closers in the business. He was extremely handsome and almost unbearably confident. Almost nobody ever got a hit against him when he was brought in for the last inning. Gibson was as gimpy as it is possible to be. He looked old at the plate, unshaved, and hunched over. He swung widely, almost desperately, almost convinced he would make an easy out.

Eckersley threw over to first base four times to keep the Dodgers’ Mike Davis from stealing second. Gibson was clearly having trouble swinging the bat. “He can’t push off, and he can’t land,” Scully said. “He’s shaking his left leg, making it quiver like a horse trying to get rid of a troublesome fly.” Gibson fouled the ball away several times, and Eckersley eventually threw three balls outside the strike zone.

So the whole game came down to one final pitch, Eckersley’s 14th of the at-bat.

And here’s the pitch:

Gibson swung awkwardly (almost like a cricket batter) and drove the ball deep into the right field stands. It was a walk-off home run with two outs in the bottom of the ninth. What could be better than that? The crowd went wild. Bob Mezey went nuts in my living room. The Dodgers’ dugout erupted. The chubby coach, Tommy Lasorda, lurched out of the dugout and “sprinted” toward home plate, gamely trying to jump in triumph a few times along the way. Scully was perfect: “In a year that has been so improbable, the impossible has happened,” he said. He added, “Now the only question was whether he could make it around the base path unassisted.”

Then Gibson, who was limping around the bases and favoring his right leg, rounded third and performed the greatest double fist pump in sports history. In fact, all subsequent fist pumps, including Tiger Woods’ superb version at the Masters in 1997, originated in Gibson’s 1988 moment of sports apotheosis.

“Look at Eckersley, shocked to his toes,” Scully said. “They are going wild at Dodger Stadium; no one wants to leave.”

In a 1995 poll, Gibson’s miracle home run was voted the “greatest moment in LA sports history.”

I cried openly as I watched the clip (for the 20th or 30th time in my life). What was I crying for, surrounded by strangers with far better baseball credentials than mine in the middle of the Hall of Fame? Well, partly for the “thrill of victory and the agony of defeat.” Partly for Gibson’s demeanor after he reached home plate, a mixture of ultimate triumph but not a little surprise. Partly, as Scully said, for the sheer improbability of the result. Partly because I had shared that moment with three of the best people I ever knew when I was young, and the world was all before me. Partly because 60,000 people were in true ecstasy together at a ball game in Los Angeles. Partly because Scully was the perfect sportscaster for that extraordinary moment of drama. I cannot imagine Harry Caray, Al Michaels, Joe Garagiola, or Mel Allen doing it as well.

In many respects, the Baseball Hall of Fame is lost on me. I haven’t stayed current with the game into the 21st century. I need to be there with someone who really still loves and follows the sport. I did not feel out of place, but I reckoned I was probably the most ignorant person in the building, like someone who lives for NASCAR suddenly finding himself in Britain’s National Portrait Gallery and recognizing only a handful of worthies — Princess Diana, Shakespeare, and Churchill — and bewildered by the rest. I gravitated to the little clusters of conversation throughout the building, hoping to learn from the “experts.”

The Amazing Museum Shop

After a couple of hours in the museum, needing to hit the road, I browsed in the tremendous bookstore with its hundreds of titles. Then I moved on to the giant museum shop (the word “shop” does not do it justice) where I thought I would buy a baseball signed by Nolan Ryan or Mark McGuire for one of my friends. Still, when my application for a second mortgage got stuck in paperwork, I had to settle for a couple of postcards and a pack of cards honoring the Negro League. It was great fun to watch boys and girls of about 12 years old literally dragging their parents through the aisles to some cherished souvenir that the parents were almost certainly not going to buy for them. No such veto was available to the 45-year-old overgrown boys. Several of them spent a very large amount of money to obtain some treasured memento (a ball, a bat, a plaque, one of those matted and framed ensembles of an autograph, a beautiful photograph, maybe a three-dimensional object like a jersey or a glove). It was no different, except in net worth, from the New York lawyer at a Sotheby’s auction buying a Picasso drawing for an amount they couldn’t afford.

As I stood gazing at impossibly expensive autographed baseballs, the clerk, a 19-year-old man who looked as if he had just left an Eagle Scout meeting, asked me if I was looking for “anything in particular?” I said I was browsing. “What’s your team?” he asked. “When I was a boy, it was the Twins.” He took on a look of pity and condescension. Then I made things worse by invoking the name of my boyhood hero, Harmon Killebrew. “I’m afraid we don’t have anything for him, but if I remember, he was inducted sometime in the 1980s, and you can probably find his plaque in the Hall.”

Harmon Killebrew was a home run specialist (573) who hit 49 home runs in a single season twice, in 1964 and 1969. He ranks 12th on the home run list, just below Mark McGwire (583) and just above Rafael Palmeiro (569) and Reggie Jackson (563). Killebrew’s top salary came in 1973 at $105,000.

As I drove away from Cooperstown in my rig towards the Erie Canal, I determined to visit the NFL and NBA halls of fame and the Rock and Roll, Country Music, Cowboy, and others as I happen upon. But I doubt that the NFL or the NBA can bring me the same emotional satisfaction. There is something about baseball. Ken Burns, as always, was right. I lament what has happened to Major League Baseball, and I now usually confine my visits to bush league stadiums, where something of the original feel of baseball still prevails.

I’ve seen games in five Major League parks in my lifetime, and I’m about to sit through a White Sox game (against the Toronto Blue Jays) in Chicago with my friends Dennis and Russ. Russ really knows the game, as they say, and has contributed articles to several baseball books.

Meanwhile, come on, put Pete Rose in, the poor bastard.

Over the next few months, Clay is shadowing Steinbeck’s 10,000-mile trek around the USA (and making a few detours of his own). Clay’s expedition is a central part of LTA’s big initiative to explore the country and take the pulse of America as it approaches its 250th birthday. Be sure to follow Clay’s adventures and subscribe to our newsletter.