John Wesley Powell, Edward Abbey and hiking Canyonlands National Park.

Moab, Utah, October 2024 — Listening to America’s intrepid scout, Frank informed us, though he desired it with all of his heart, he could not make the 11.5-mile hike to and from the confluence of the Green and Colorado Rivers in Canyonlands National Park because he had a flareup of his smallpox. So apparently, the World Health Organization’s declaration that smallpox — once the scourge of hundreds of millions of people worldwide — had been eradicated was … er, imprecise. Or maybe Frank said diphtheria.

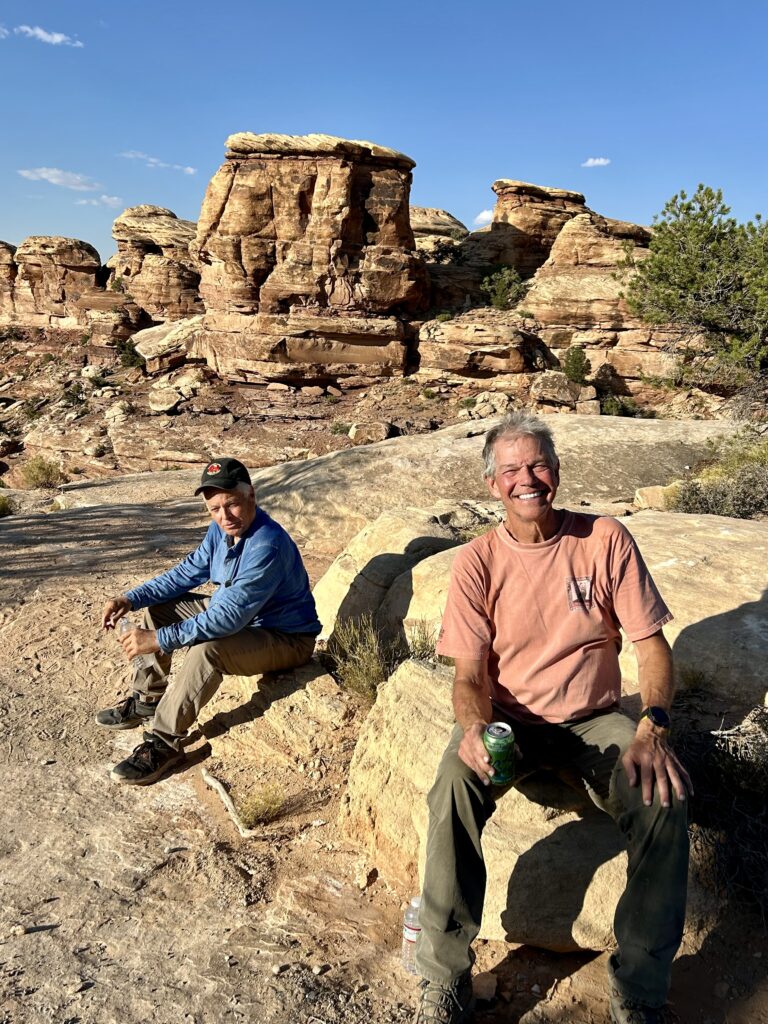

Dennis was game. I had suggested the hike. I had done it once before long ago. Turns out it was very long ago. Our colleague Dr. Ryan, the Southwest archaeologist, left Dennis and me in her dust in both directions. Showoff! At least she always stayed within sight so we wouldn’t get lost along the way.

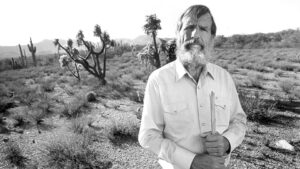

We were in the heart of Edward Abbey Country

It’s billed as a strenuous hike. It was 90 degrees or so. We started early to avoid the worst of the heat, at least on the way out. It’s only 5 miles from the parking lot to the confluence, but there is much up and down, including one ladder, and not a little scrambling here and there. You must pass through several starter canyons before getting to the main event. We stopped every 30 minutes or so to drink water and exclaim over the unbelievably beautiful views in every direction. We looked out on the Needles and the Maze, distant mountains (the La Sals), and a jumble of seemingly impenetrable canyons (with or without water) in every direction.

By the time we finally got to the confluence, we were ready for lunch. Because this was an Edward Abbey reconnaissance trip, each of us, independently and without mutual consultation, had brought Abbey snacks: almonds, walnuts, and raisins. I wish I had brought a small bottle of wine to celebrate, but I wasn’t sure my body would hold up against 8 additional ounces of pack weight! We sat in the shadow of a huge freestanding boulder that was uneasily perched on the pink sandstone just over our heads.

The confluence of the Green and the Colorado is the very definition of the sublime — something so outside the norm, so nearly unbelievable as a feature of nature, so deep a chasm, with two similar but distinguishable rivers coming together in the middle of nowhere, each having incised a canyon more than 1,000 feet into the Earth. The two canyons look identical from above, but the Green River is green (or greenish), and the Colorado River is reddish. For a couple of hundred yards downstream from the confluence they seem reluctant to comingle. But then they do.

It’s one of America’s great destination hikes. Its visual greatness is all the greater because you have to earn it with your legs and back. There is a jeep trail that you can opt for, but we looked on that with derision and contempt. At one point, the hiking trail intersects the jeep trail, and I thought I glimpsed Frank riding in a commercial jeep on what seemed like a throne, clutching a blended margarita (with a drink umbrella) in one hand and a Chinese folding fan in the other. I cannot be sure it was Frank, through the mental cloud of my heat stroke, but he was evasive later at dinner.

John Wesley Powell

As we sat on the lip of the abyss, I thought of one of my heroes, John Wesley Powell (1834-1902). In 1869, with nine other frontier types, Powell floated the Green and Colorado Rivers in four, then three, wooden dories from Green River Station in Wyoming all the way out to the other side of the Grand Canyon. So far as we know, he was the first person ever to do so. The explorers were lucky to survive — it wasn’t the river that got them, but near-starvation. And fear. Three of his men deserted (a slightly too strong term) at what is now known as Separation Rapids just a day or two before they would have come out of the Grand Canyon at Grand Wash Cliffs. On the basis of this great adventure, Powell gained national fame and, more importantly, political and cultural influence. He went on to be an agrarian and hydrological revolutionary who tried to save the West from the interstate water wars that have never ceased to pit the lower Colorado River states (Arizona, Nevada, and California) against the upper (Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah); and California against everyone else. Water, said the author of Cadillac Desert, Marc Reisner, tends to flow uphill toward money.

Powell’s 1878 Arid Lands Report warned that water would be the most significant challenge to the development of America west of the Hundredth Meridian, which bifurcates the Great Plains from North Dakota down to the Gulf of Mexico. Nobody listened. Powell advocated what he called “watershed commonwealths” in the West so that the great rivers (the Colorado, the Yellowstone, the Snake, the Missouri) could be managed as integrated bioregions. His final warning came at the International Irrigation Conference in Los Angeles in 1893. Gentlemen, he said, “When all the rivers are used, when all the creeks in the ravines, when all the brooks, when all the springs are used … there is still not sufficient water to irrigate all this arid land.”

Powell was booed. They shrugged off the concerns of the wisest man in their midst. The water conflicts that are now roiling the West in the face of prolonged drought and global climate change are precisely what he was trying to help us avoid.

The Powell Expedition reached the confluence of the Green and Colorado on July 16, 1869, 53 days into their 99-day journey. By now their food supply was already running out. Powell wrote, “Soon I see [Billy] Hawkins down by the boat, taking up the sextant, rather a strange proceeding for him, and I question him concerning it. He replies that he is trying to find the latitude and longitude of the nearest pie.”

As we sat in awe on the brink of the canyons, I recited John Wesley Powell’s great passage about the moment his expedition first breached the portal of the Grand Canyon itself:

“August 13 — We are now ready to start on our way down the Great Unknown. Our boats, tied to a common stake, chafe each other as they are tossed by the fretful river. They ride high and buoyant, for their loads are lighter than we could desire. We have but a month’s rations remaining. The flour has been resifted through the mosquito-net sieve; the spoiled bacon has been dried and the worst of it boiled; the few pounds of dried apples have been spread in the sun and re-shrunken to their normal bulk.

“The sugar has all melted and gone on its way down the river. But we have a large sack of coffee. The lightening of the boats has this advantage; they will ride the waves better and we shall have but little to carry when we make a portage.

“We are three-quarters of a mile in the depths of the Earth and the great river shrinks into insignificance as it dashes its angry waves against the walls and cliffs that rise to the world above; they are but puny ripples, and we but pigmies, running up and down the sands, or lost among the boulders.

“We have an unknown distance yet to run, an unknown river yet to explore. What falls there are, we know not; what rocks beset the channels, we know not; what walls rise over the river, we know not.

“Ah, well! We may conjecture many things. The men talk as cheerfully as ever; jests are bandied about freely this morning; but to me the cheer is somber and the jests are ghastly.”

I recited the whole darn thing from memory while my companions sipped water and gazed into the chasm and the seemingly diminutive rivers at the bottom. I was proud of myself. I thought my friends would look at me with deep admiration, with a new sense of respect. I thought they would now regard me as a humanities hero who could recite just the right passage at just the right moment. But they just looked at me with the expression, “Yeah, what have you done lately?” or “Oh, yeah, what else you got?” or “Yeah, I’d cut that by 200 words.” But if Frank the Scout had recited the Pledge of Allegiance or the Lord’s Prayer at the confluence, they would have given him the Nobel Prize. And Frank was having an extended afternoon nap back in Moab. Such is the life of the humanities scholar. I’m pretty sure Dr. R had dozed off halfway through my recitation.

We all would have liked to have camped there as close to the edge as we dared to see the canyon at sunset and the gloaming. To burrow into sleeping bags as the temperature dropped after midnight. We wanted to wait to see the stars as far from manmade light as possible. Think of the confluence at first light, when someone gets up to brew some French press coffee. One of us, I won’t say which, has some pretty high coffee standards.

But no. We turned back.

In that whole seven-hour day in one of America’s great national parks, we saw exactly three other people on the trail. When we read in the press that the national parks are overwhelmed with visitation, that we are loving the national parks to death, we need to be careful about over-generalization. I’ve been in eight national parks since the end of April 2024, and only Yellowstone was overcrowded. In Yellowstone, someone sees a bear or what they think might be a bear, so far away that, in some sense, it no longer matters. Within minutes there is a 75-car traffic jam. Rangers come to get things moving. They represent a kinder, gentler version of the New York traffic cop. People huddle together to share binoculars, and someone says, “Look, it moved its paw. I think that was its paw.”

But Arches National Park (Abbey’s Park) was not overcrowded, though we had to apply for a timed entry on a weekday October afternoon. Canyonlands NP was empty, at least where we explored it. (There is a more popular vista near Moab.) Then Petrified Forest NP, which I explored after my friends returned to their lives, was empty. Part of our advantage was that we were willing (except for Frank, who said he had a rare triple toothache), to hike off concrete and asphalt in search of beauty and solitude. Most people who visit the national parks want to stay on asphalt. My father was such a person. So was my mother, but she was too proud to admit it. If you are willing to hike on the unmediated surface of the earth, you can have almost every national park, more or less, for yourself. We’d be healthier, saner people if our prevailing asphalt-only predilection did not exist (I’m channeling my inner Abbey here). Still, it has the unintended effect of giving those willing and able to hike on trails a true advantage. If one prime purpose of the national parks is to permit weary, overworked, overstimulated, and harried Americans the opportunity to slow things down, unhitch the electronic tether, and refresh the human spirit in nature, it’s all right there for those who hit the trails.

The return hike was more taxing than the outbound. It was hot now, among other things, and our legs were heavy. Well, the legs of two of us. We took more breaks this time. There was some inward whimpering, at least in my heat-addled cranium. At one point I reckoned it would have just been easier to throw myself over the lip right into the abyss and get it over with. My two colleagues sensed this and said they would regard it as a great inconvenience if they had to call in a medivac or a coroner. So I struggled out on my own recognizance.

When we got to the vehicle where Dennis had left a large cooler full of ice and cold drinks, I felt like Chevy Chase in National Lampoon’s Family Vacation, when — after hiking all day alone across the desert in great heat — he says, in that neurotic Chevy Chase schtick language, “Hey, anyone want a pop! How ’bout a pop!!”

We drove back to Moab in silence. It was an amazing, deeply satisfying day. I tried to lie down in the back seat, but my leg cramps kept tossing me to the top of the interior ceiling. When we got to Moab, Frank was waiting at a corner dine-outside restaurant that had been recommended to us. He said he had stood in line at great personal sacrifice for three hours to secure us a table. Hungry and thirsty as we were, we chose to believe him. Frank said at dinner, “To eat or not to eat, that is the question,” my companions nearly carried him on their shoulders back to the car.

Edward Abbey’s Desert Solitaire is a brilliant, crabby anthem to an untrammeled West. He was appalled by industrial tourism back in 1968. Imagine what he would have to rail about now. And yet we friends had shared an unforgettable experience in just the way Abbey would have suggested: on foot, with enough body strain to make it interesting, with a lively sense of history and a renewed sense of wonder.

A perfect day in the outback of America.