I was listening to an audio biography of Joseph Banks, the great British naturalist who sailed with Captain James Cook on the first voyage, who made Kew Gardens in Britain one of the world’s finest, and who was the president of the Royal Society — among much else, not all so admirable it turns out.

Because I am traveling America, I’m reading travel books of every sort, including recently Hampton Sides’ new study of Captain Cook’s third (and fatal) voyage, The Wide, Wide Sea: Imperial Ambition, First Contact, and the Fateful Final Voyage of Captain James Cook. I don’t know how it works for you, but when I get fascinated by a topic like this, “way leads on to way,” and I wind up reading in and around the subject in all sorts of directions. You cannot make sense of James Cook’s travels without coming to terms with Joseph Banks, the wealthy aristocrat with a deep passion for botany who accompanied Cook on the first voyage. Banks is often compared to Thomas Jefferson, another enlightened amateur who zealously sought knowledge of what then was called the Natural World.

So I have been reading Toby Musgrave’s The Multifarious Mr. Banks: From Botany Bay to Kew, the Natural Historian Who Shaped the World, and listening to Peter Fitzsimons’ James Cook: the Story Behind the Man Who Mapped the World.

Because of our time’s new (and important) cultural sensitivities, it is essential that we rethink most of what we thought we knew. What follows is my attempt to come to terms with the amazing Joseph Banks’s mixed legacy.

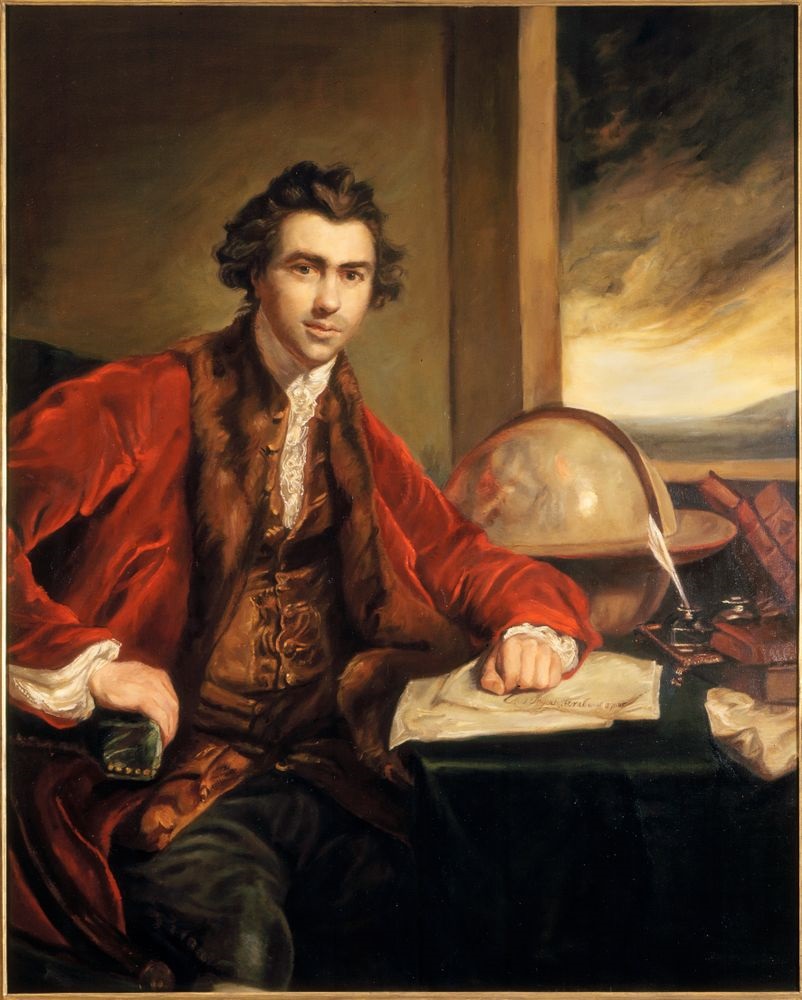

Joseph Banks (1743-1820)

One of the great figures of Georgian England, Joseph Banks traveled with Captain James Cook on the famous first voyage (1768-1771) — to Tahiti to observe the Transit of Venus for the British Admiralty and the European scientific community. He was an exemplar of the Enlightenment, as was America’s Thomas Jefferson, born in the same year across the Atlantic. (Jefferson died in 1826, six years after Banks.) Jefferson and Banks are frequently regarded as a transatlantic pair of enlightened amateurs and patrons of exploration, though they never met and did not correspond. Jefferson knew and admired the work of Banks, but it is not clear that Banks would have regarded Jefferson as anything more than an American rebel and — later — the republic’s third president. For 41 years, Banks was the president of Britain’s Royal Society. For 18, Jefferson was the president of the American Philosophical Society, created by Benjamin Franklin, who knew them both.

What should we do with our postcolonial ambivalence about Joseph Banks?

I used to think better of Banks, but now that I have read a couple of biographies, I admire him more and like him less.

After returning from his voyage with Cook, he jilted a young woman to whom he had been previously betrothed (Harriet Blosset) in an unconscionable way. He left her suddenly without informing her of his plans on a multi-year voyage around the world from which he might never return. Once she had come to terms with his cruel and unannounced departure, she spent his long absence sewing him lovely and intricate waistcoats to wear when he returned to England. When he finally returned to England in July 1771, Banks didn’t bother contacting her. She learned of his return in the newspapers, where he was universally lionized. Miss Blosset had to contact him to seek an explanation for his appalling behavior. He first tried to put her off with a letter, but she insisted on an “interview,” as such things were called then. Eventually, he paid Blosset a lump sum of 5,000 pounds sterling (about a million dollars in today’s currency) to make her go quietly away. In this, he was simply a cad.

Now famous and the most sought-after dinner companion in Great Britain, Banks demanded such special treatment for joining Cook’s second voyage that when modifications had been made to the ship, Resolution to accommodate him, the vessel was so unstable that it could no longer make the journey. The Resolution had to be restored to its original condition to make it seaworthy again. At this point, Banks threw a mighty tantrum, withdrew from the expedition with aristocratic hauteur, and used his power, immense wealth, and social position to quash any significant social or political criticism. He was entirely in the wrong, and of course, he knew it. At the end of his long and productive life, he was still trying to explain his colossal mistake, perhaps even to himself.

During and after his world travels, Banks sought out and purchased indigenous skulls for his German friend Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752-1840), who was studying the skin and crania of the world’s peoples to make what we now see as racist classifications of human capacity. In 1795, Blumenbach published a treatise maintaining five varieties of humankind: Oriental, American Indians, Caucasian, Malay, and Ethiopian. In many respects, Blumenbach bequeathed us the “modern” scientific concept of race and made it clear that he regarded “Caucasians” as the most highly developed race. Some of Blumenbach’s terms have persisted into the beginning of the 21st century. Banks was only too glad to procure skulls for his continental friend, including by having them removed from the sacred sites of indigenous peoples.

Banks treated Tahiti as a free love zone, getting and giving STDs as he slept his way through Polynesia. He was a prominent European intellectual who behaved (as a young man) like a frat boy.

When two of his attendants, both black, died of hypothermia on a botanizing excursion he led at the bottom of South America, Banks recorded their deaths with studied indifference; when his greyhound died on the Endeavour on the return voyage to England, Banks was overcome with sorrow.

He appropriated the work of some of his assistants by insisting that everything they did on his behalf belonged exclusively to him.

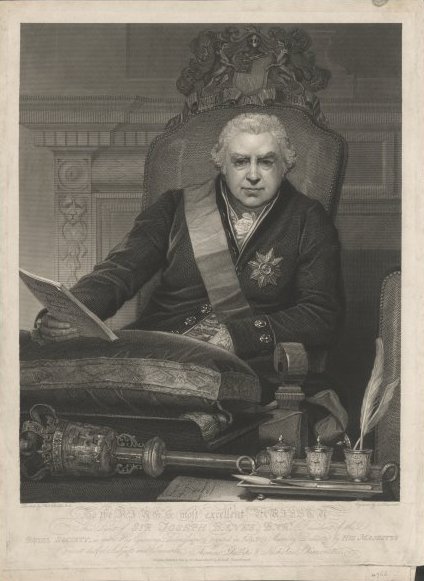

Later in life, Banks descended into such self-satisfied luxury that he ballooned up until he could barely walk, could no longer work with plant specimens, and suffered from gout. The once handsome youth so full of promise eventually became an old, fat, entitled man who wallowed in his fame and power.

And yet, on balance, perhaps there is more to admire in Banks than to decry.

He was a friend of Britain’s King George III, and he used his connection to advance the Republic of Letters and elevate Kew to the first rank of botanical gardens worldwide. Banks and “farmer George” frequently strolled Kew Gardens, talking botany and agriculture together. He was an active member of more than 70 clubs and societies, most but not all in the British Isles.

He was genuinely indefatigable in his pursuit of new plants all over the world. He was outspoken in his frustration when shore conditions prevented a landing, when Captain Cook decided he could not spare more time for botanizing, and when local authorities refused to permit Cook’s crew to visit their environs. He is said to have collected and identified more than 30,000 plant specimens during his amazing career. As a botanical collector, he has no peers in history, not even Linnaeus.

Banks smuggled fiercely guarded Merino Sheep from Spain and introduced the breed to England, New Zealand, and Australia. Spanish authorities were unwilling to share this prize strain of sheep with its geopolitical competitors. Merinos were immediately recognized as the best sheep in the world. In an unrelated quest, America’s greatest agrarian visionary, Thomas Jefferson, obtained a pair of Merino sheep, sang their praises in his voluminous correspondence, and made their progeny freely available to farmers and agricultural societies throughout the United States.

Banks helped establish a colony of convicts in eastern Australia so that British malefactors could start their lives over in a far corner of the world rather than perish on the gallows or in the fetid prisoner ships (the hulks) in the Thames estuary. From his own great wealth, he founded a large number of voyages of science and discovery.

He brought celebrity and international attention to Captain Cook’s first voyage in a way that Cook himself might not have been able to accomplish.

Banks’s biographer, Toby Musgrave, summarizes his genius well. “Banks became an acknowledged expert in a wide range of subjects, including agriculture, botanic gardens, canals, cartography, coinage, colonization, currency, drainage, earthquakes, economic botany, exploration, farming, leather tanning, Merino sheep, plant pathology, and even the plucking of geese.”

And Yet …

Given the multicultural sensitivities of our time, thanks to the cultural revolution that began in the 1960s, we cannot now help seeing Joseph Banks as an agent of the British Empire; more, in fact, than Captain Cook, who was performing the duties set for him by the British Admiralty. Banks was a full-tilt British imperialist without the slightest doubt about the superiority of European (and British) civilization, an advocate of British commercial domination of the world’s oceans, and a profoundly Eurocentric anthropologist.

He was, of course, a man of his times, but his partner in discovery, James Cook, was more culturally sensitive in measurable ways. One of the sponsors of the voyage, James Douglas, the 14th Earl of Morton, in his Hints for the Consideration of Captain Cook, urged the explorers to observe “the utmost patience and forbearance with respect to the Natives of the several Lands where the Ship may touch,” to “have it still in view that shedding the blood of those people is a crime of the highest nature: — They are human creatures, the work of the same omnipotent Author, equally under his care with the most polished European; perhaps being less offensive, more entitled to his favor,” and always to remember that the indigenous peoples “are the natural, and in the strictest sense of the word, the legal possessors of the several Regions they inhabit.” Morton wrote, “No European Nation has a right to occupy any part of their country, or settle among them without their voluntary consent. Conquest over such people can give no just title; because they could never be the Aggressors.”

Jefferson as the American Joseph Banks

Sometimes, Thomas Jefferson is likened to Banks, but this is a weak analogy. Jefferson was a gifted amateur, an enlightened dilettante, but he did not have the drive, means, or scientific discipline of Banks. Jefferson had a famously weak stomach for sea travel. He would surely have agreed with the English man of letters Samuel Johnson, Banks’ contemporary, who said, “Being in a ship is being in a jail, with the chance of being drowned.”

Jefferson had none of Banks’ vast wealth.

Jefferson, like Banks, thought of himself as a patron of exploration and science and a disseminator of the best ideas of his time, but he was essentially a gifted dabbler. On the other hand, Jefferson had an essential modesty of spirit that would have made it impossible for him to throw his weight around like Banks. Needless to say, their views of King George III were fundamentally different. It is impossible to imagine Jefferson dallying with indigenous women in the Pacific, his enslaved lover Sally Hemings notwithstanding. Because of his great wealth and social standing, Banks could buy anything he needed, including his participation in Cook’s first voyage, for which he spent 10,000 pounds sterling. Banks helped to expand the British Empire, while Jefferson gave the first of his adult years to prying the American colonies out of the British Empire and the rest of his life to establishing an isolationist agrarian New World republic to protect the lives, liberties, and the pursuit of happiness of the American people.

Banks belonged to the British gentry. He had vast and profitable estates in several English counties. He lived as an entitled aristocrat on his landed income, bought whatever he coveted, including access, and bought off scandal and even criticism. Jefferson was in serious debt most of his life, bankrupt at the end. Even if he had been terribly rich, I doubt that Jefferson would have pursued a life of ostentatious luxury. Jefferson acquired (usually on credit) books, scientific instruments, musical scores, good wine, and fine paper and ink, but not the dross of extreme wealth. He liked to say that he would rather be a free man in homespun cloth than acquire all the most significant fruits of life at the expense of his self-respect and independence.

What Should We Conclude? It’s Not Clear

It’s hard not to think of Banks — once you get to know him — as sharing some of the character of James Steerforth in Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield: a rich and entitled swaggerer and seducer who leaves a wake of broken hearts — and an agent writing cheques — behind. But unlike Steerforth, Banks had an indefatigable commitment to advancing human knowledge at home and abroad. In this, he was precisely like Thomas Jefferson.

Until recently, Banks’ private life was not regarded as sufficiently troublesome to cast a cloud over his great achievement. Nor, until the last 50 years, was Banks’ cultural arrogance and undisguised commercial imperialism regarded as problematic. As Hampton Sides acknowledges in his recent book about James Cook’s third voyage (1776-79), The Wide, Wide Sea: Imperial Ambition, First Contact, and the Fateful Final Voyage of Captain James Cook, it is now impossible to write about Cook and most of his compatriots without seeking the right balance between admiration for these confident and determined men of the Enlightenment, and deploring their blind self-assurance about the right of Europeans to lord it over all the rest of creation.