I have just returned from a few days in New York, where I was interviewed for an eight-part documentary series. I won’t go into more detail now, but the series will appear on the History Channel sometime in the next 18 months. The interviews covered eight incidents and eight themes from the history of the American West, beginning with the Battle of Fallen Timbers in Ohio in 1794, which effectively crushed the Native American alliance attempting to keep the Anglo-Americans from grabbing all of what became the state of Ohio.

I want to take a minute to provide a glimpse into the sad and lonely life of the “talking head.” That’s the “expert” the documentary filmmaker quickly and routinely cuts back to for three sentences of commentary. It sounds glamorous, doesn’t it?

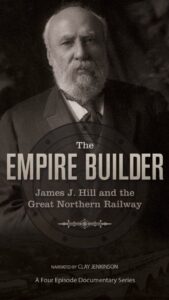

I live for this. To read books, write, lecture, lead cultural tours, host online humanities courses, travel America (and beyond), and sit for interviews in documentary films. I’ve had the great good fortune to be in five of Ken Burns’ documentaries (Thomas Jefferson, The National Parks, The Roosevelts, Benjamin Franklin, and most recently The American Buffalo); in several documentaries on Theodore Roosevelt and the River of Doubt; and Doris Kearns Goodwin’s five-part Theodore Roosevelt. I’m always thrilled, honored, and humbled to get the call. I’ve also been the on-camera narrator of several documentaries and off-camera narrator for several others, including Stephen Sadis’ The Empire Builder: James J. Hill and the Great Northern Railway.

To get ready for this latest interview — on EIGHT different subjects! — I made 200 pages of tightly packed notes. I made lists of essential facts (date, place, name of national monument or historic site), and then lists of talking points. I printed out 50 pages of internet commentary on each subject, reread parts of a couple of dozen books, wrote out key quotations, memorized a few of them, and voiced short commentaries in front of the mirror to get the pacing right and to know when to stop talking.

Ken Burns once told me: You want to know the key to being in my documentaries, all other things being equal? Stick the landings.

What to wear? I belong to the low-maintenance camp of adult professionals. Much of what I wear comes from Walmart or Target (though I buy good shirts), with occasional visits to a few high-enlightenment emporia like REI. My hair gets an average of one five-second brushing daily, and that’s it. But this gig mattered to me so much that I packed four possible Talking Head costumes: 1) a blue blazer and khakis look; 2) the open-sleeved cattle baron’s vest; 3) a tweed suit and tie; 4) or my snazzy tangerine-colored Edward S. Curtis leather jacket.

The film folks chose the leather jacket, something maybe Yellowstone’s Kevin Costner would wear to town on an October day.

I should say something about the phrase “the talent.” When I first heard these words several decades ago, I swelled up like a man of consequence.

I flew to New York, Ubered to my hotel in Brooklyn, and found some excellent Thai food within walking distance. Then I tried to get a good night’s sleep, but I kept waking up unsure if it was Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain, or Sylvia Plath who said, “Suppose you were an idiot and suppose you were a member of Congress, but I repeat myself.” Then, I’d turn on the light and shuffle my notes for a while. Was it Jefferson or Napoleon who said all men are created equal? It’s amazing how much information runs through your brain like a colander. At some point during the night, I just wanted to slink away to the airport and go home to lick my wounds.

The makeup artist brushed my face for about two minutes. A sound man fitted me with a lapel microphone; I got up on a chair on a platform above a dais. They know what they are doing, these folks, and they had set up their shoot several days before I arrived. Of course, I was only one of several talking heads being interviewed for the series. They know what they are doing. I repeat, the only weak link is the talent.

I should say something about the phrase “the talent.” When I first heard these words several decades ago, I swelled up like a man of consequence. It seemed like a term of genuine respect, possibly even admiration. But it soon came clear to me that the people who make these films define “the talent” as 1) the very highly imperfect and annoying human being that stands between the filmmakers and the completed product; 2) the weak link in an otherwise exceptional project; 3) the blathering, blithering blowhard from whose endless commentary perhaps one or two salient comments might be extracted; 4) the least pleasurable part of the process; 5) the pain in the ass who thinks s/he is essential to the success of the project.

The sooner the talent learns this grim truth, the better. The true professionals don’t even try to use the term with respect. “We’re ready to go, where’s the frickin’ talent?” “Would you tell the talent to stop adjusting his hairpiece?” It’s a bit deflating to realize that all they want you to say is, “The war ended with the restoration of the status quo ante bellum,” and then go home. Or “Custer’s wife Libby gave the last 50 years of her life to defending the Boy General against his detractors.”

Now go home!

I was very fortunate this time. My excellent interlocutor asked a warm-up question, and words began to pour out of my mouth — undoubtedly mostly gibberish — before I found my rhythm and began to deliver bromides and nostrums, often delivered with stammering uncertainty, often in interminable paragraphs. Some days you have it, and some days you don’t. Knowing stuff is one thing; getting it out of your mouth concisely and coherently is another.

When Ken Burns has interviewed me, I always get to his studio in Walpole, New Hampshire right on schedule. They slap a little face paint on me and set me in the chair. The subject is X — say Ben Franklin — but I have no idea what questions will be asked. Suddenly, Burns enters the studio with all his beauty and brilliance and sits across from me, not more than 3 feet away. The cameras roll. With his amazing visage, Burns looks over at me and says, “So, tell me about Ben Franklin.” Just like that. And instantly, I become a parody of Jackie Gleason in The Honeymooners when he stammers: “bubba, buh, muh, Hubba…” or John Ritter in Three’s Company when his landlord asks a question about the sleeping arrangements in Ritter’s apartment.

I had two interlocutors in the New York shoot. They were both outstanding. I attempted to be coherent, factual, forthright, and fully present for three straight hours. Between South Dakota memory cards, I wanted someone to roll up on a stool, throw wet sponges on my face, and say, through a long grimace, that there is still time to throw one good punch.

“I coulda been a contender.”

Then it was over.

Even before they ushered me out onto the mean streets of Brooklyn at dusk, I begged for a re-interview. (I always do, and of course, it never happens). I told them I would really be ready next time. I told them I would come back at my own expense. I offered to buy the producer a new Jeep. I said I was suffering from a rare form of diphtheria and was not at my best. I told them my brother was in intensive care in Peru.

For the rest of the night, I reran the interview in my head and cursed the day I was born. I realized that I had failed to say most of the good things I had wanted to say, and what I did say was rubbish. I took a long walk and kicked myself around the city’s dark streets in a perfect symphony of self-loathing. I texted the director and said, “Actually, that happened in 1854, not 1876. Can you fix that in the post?”

Alas. I will spend a lot of time on the cutting room floor. But it was pure joy to be a part of something this big.

One of the strange things about this process is that I won’t know some important things until the series launches. 1) Am I in it at all? 2) Did I say moronic things that will hang over my head for the rest of my life? 3) Will I be canceled or denounced? 4) Will I get marriage proposals from gorgeous women who love historical documentaries? 5) Will the editors have chosen the least interesting things I had to say and none of the points I worked hard to formulate? 6) Will this get me a gig on Comedy Central?

Truly. I’ve never known whether I am even in a film I’ve been interviewed for or how long it until it comes out. And to sit in an auditorium opposite a giant screen with an audience of 100 and see yourself blown up to monstrous size, saying silly things (“Hamlet was depressed”) is excruciating. I always wear a Nixon mask to the premiere.

As I flew home to Dakota — exhausted, spent — I said to myself, “When you get home, sort your notes and file them in the right place because they may call to fact check, and there is at least an outside chance that you will get a second interview.”

I’ve been home for a week and have yet to file the notes. This I will not fail to do.

Is it worth it? Absolutely.

Just give me one more chance to get it right.