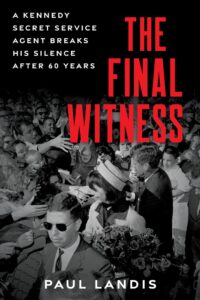

Clay reviews a new book by Paul Landis, a former Secret Service agent in President Kennedy’s motorcade on November 22, 1963. A first-hand witness to events that day, Landis was never interviewed by the Warren Commission and kept his recollections private, including details about a key piece of evidence.

The minute I heard that former Secret Service Agent Paul Landis was publishing a book entitled The Final Witness, I pre-ordered it. It arrived yesterday, and I read it in a single evening. I’ve read dozens, maybe scores, of books on the assassination of John F. Kennedy, including, again, just a few weeks ago, William Manchester’s magnificent Death of a President.

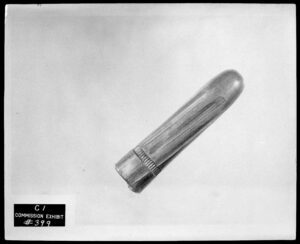

On page 166, Landis reveals that after Mrs. Kennedy and the already-dead president were extricated from the back seat of the presidential limo at Parkland Hospital in Dallas, he found a nearly intact, 2-inch bullet on the top of the back seat where it meets the frame of the vehicle. In the wild rush of things, fearing that a photographer or souvenir collector might pocket it, agent Landis picked up the bullet himself, put it into the pocket of his suit jacket, and went inside the hospital.

Later, he placed the bullet on one of the gurneys that had brought the president and Texas Governor John Connally into the emergency room. That’s where it was found. It is now universally known as the Magic Bullet.

That we are only learning about this fundamental disturbance of the 20th century’s greatest crime scene 59 years and 10 months after the assassination is deeply troubling. Agent Landis had a legal and moral duty to explain what he had done immediately to his superiors, to the FBI, and later to the Warren Commission. Undoubtedly, he was traumatized by seeing the president’s head explode at close range, but to tamper with a crime scene — even if for good reason — and then not to report what he had done is a serious dereliction of duty.

If agent Landis’ concern was that a stranger might pick up the bullet, he should at the very least have called a photographer over to take a photograph of the bullet exactly where he spotted it or called over a policeman or other reliable person to watch over the limo until the proper authorities (i.e., the FBI) could inspect the interior for clues.

It gets worse.

Traumatized, Landis did not read the Warren Commission Report (September 24, 1964) or even one of the dozens of summaries. If he had, he would have realized that his removal of the bullet distorted the Warren Commission’s attempts to construct an accurate narrative of what transpired on that terrible day. Had he read the report, he would have been in a position to contact the Commission, tell his story, correct the record, and enable everyone — from average citizens and historians to conspiracy theorists — to be able to work from a reliable and accurate description of the crime scene and its aftermath. Not to have done so is inexplicable.

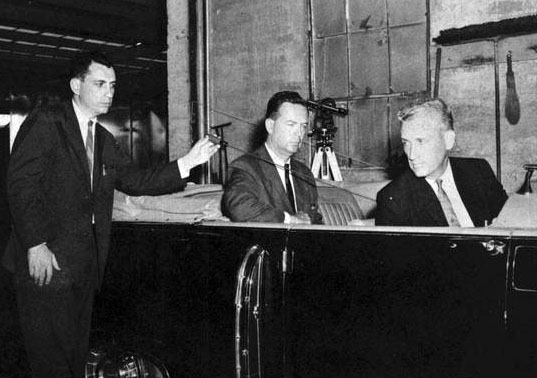

Nor has Mr. Landis, who retired from the Secret Service in the spring of 1964, read even a few of the countless books written on the subject, books which try to sort out how the Magic Bullet could have passed through the president’s throat, and then done extensive damage to Governor Connally (including striking several bones), and yet been pristine when found on the gurney. Imagine how much confusion this act of omission has caused.

Nowhere in the book does Mr. Landis apologize to the American people for his actions or acknowledge that he should have reported the incident immediately to his superiors. He explains what he did and what finally precipitated his revelation (at age 88). Still, he serves up this fundamentally important piece of evidence as if it is of no special significance or consequence.

I’m sorry to be so hard on Paul Landis, but this matters. It matters deeply. We should have known this key fact no later than September 24, 1964. The Kennedy assassination is one of American history’s most hotly debated and obsessively written about moments. To realize now that all of those hundreds of books have been misled in this way on a question of this grave importance is inexplicable. It is dumbfounding.

The mysteries still abound. How many bullets were fired that day? Were they all fired from the Texas School Book Depository, or was there more than one gunman? Why would a bullet fired into the presidential limousine be pristine? How (forensically) did it wind up on the upper reach of the back seat? What would Arlen Spector (the Commission investigator who concocted the inherently improbable Magic Bullet story) say now? Will this 60-year-old revelation permit us to construct a more accurate accounting of those fatal minutes just before and after 12:30 pm in Dallas? Could Oswald have fired all the bullets?

I’m sick at heart to read this book and write this review. It pains me to write harshly about a man so traumatized by the assassination that he left the Secret Service, built a career entirely outside the realm of security services, and, as he says, never purposefully looked back on November 22, 1963. I hoped the book would be more, but unfortunately, it is more perplexing than clarifying. We get no adequate or satisfying explanation of why Mr. Landis made no effort to come forward with this critical piece of information in all those years. We can all feel sympathy for the PTSD that he, Clint Hill, and others have suffered for the rest of their lives, but a Secret Service agent has sworn an oath to do his duty and not let emotion get in the way. We all want to know exactly what happened at Dealey Plaza. Like a turn of a kaleidoscope, The Final Witness forces every student of the assassination to start over in trying to reconstruct the events of that day. This is not the story of a pitched battle with thousands of bullets. There were certainly only three (though possibly four or even five). It is astonishing to learn that the most crucial bullet we have was discovered not where we thought it was but was planted furtively somewhere else by an agent of the United States Secret Service (without informing his superiors).

I don’t doubt that Mr. Landis is telling the truth as he believes he remembers it. Unfortunately, his late-in-life memoir, The Final Witness, further clouds this horrific and tangled story. I think fellow agent Clint Hill’s skepticism about the revelation is important. He was there. He’s the agent who climbed onto the back of the limo to save Mrs. Kennedy when she began to climb out of the back seat onto the trunk. Agent Hill was closer and more intensely involved than agent Landis.

The story never added up. Now, it really doesn’t add up. A lone gunman who swears he is a patsy. The Commission’s and the FBI’s desperate determination to support the lone gunman theory (which limits the attack to three bullets) by imagining the trajectory of a Magic Bullet. The killing of the killer just two days after the assassination by a figure of the Dallas demimonde. Thousands of documents are still withheld from the American people. And now evidence tampering.

Truly, I am sick at heart.