Louis L’Amour is widely considered the best-selling author of Western fiction of all time. Still highly popular with readers around the globe, L’Amour has sold over 320 million books, with numerous film and TV adaptations of his work.

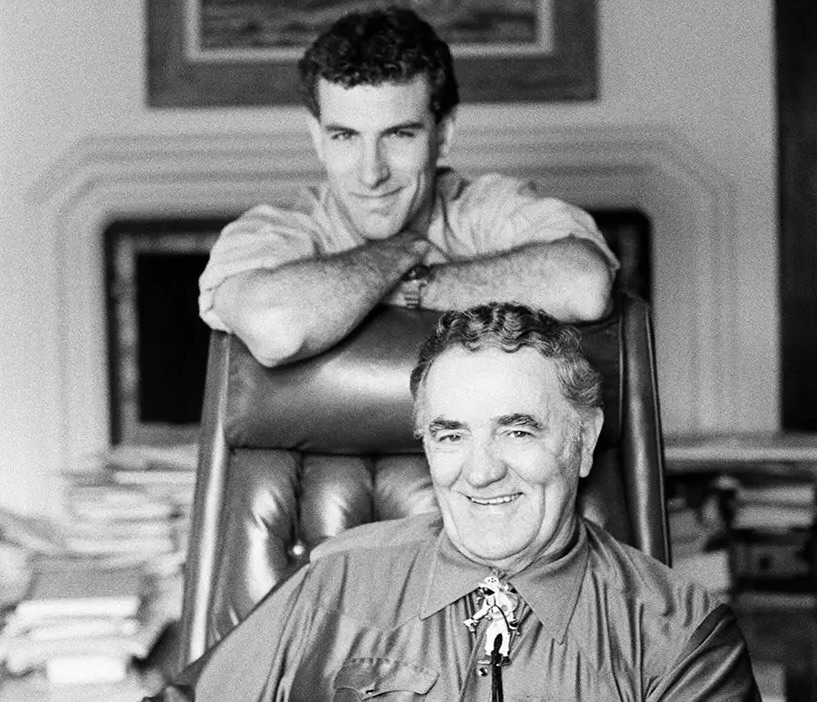

A few days ago, I had the pleasure of interviewing Beau L’Amour, son of the late writer Louis L’Amour, whose name is synonymous with the Western fiction genre. I suppose you could say pulp Western, but that is not meant to be dismissive. L’Amour’s hundred or so novels were distributed in town drug and variety stores and newsstands throughout America, particularly in the heartland, and later in supermarkets. They were printed on paper not much finer than newsprint. L’Amour was immensely popular during his long career. In preparing for my interview with Beau, I learned that his father’s novels continue to be a worldwide phenomenon. I had thought that moment had passed, the moment of the unreconstructed Western, but it didn’t and hasn’t. Among other things, Beau is his father’s literary executor. He lives in Los Angeles.

Louis L’Amour (1908-1988) began his life in North Dakota and ended it in Los Angeles. That made sense. His fascination was with the American West — and Jamestown, North Dakota, where he was born, has always been essentially Midwest. He wandered the American Southwest for several years in his youth, taking on a wide range of laboring jobs where and when he could find them. There he met the average Americans and Mexicans who populate his 89 novels and 250 short stories, men and women who spoke a taut and colorful English dialect and said things like, “A man would have to prime himself to spit in country like this,” or “He could talk a squirrel right out of a walnut tree.” Between movies and television, Hollywood produced almost 50 adaptations of L’Amour’s novels and short stories. The other, earlier, author of scores of Westerns, Zane Grey, too died in southern California.

“Confession. I’ve never been a big Louis L’Amour fan. My mother was. She read all of his books, some of them many times. She was an English teacher in a North Dakota cattle town.”

Confession. I’ve never been a big Louis L’Amour fan. My mother was. She read all of his books, some of them many times. She was an English teacher in a North Dakota cattle town. Once a year, she taught Western Lit. She was a prolific reader and could read a book a day. She loved the Western as a genre, made outlines of the “conventions” of the Western beginning with Owen Wister’s The Virginian (1902), and insisted that every Western must conform to those conventions or it was committing unpardonable heresy. Conventions: the hero loves his horse more even than his lady. The hero never starts a fight but sure knows how to end one. The hero rides off into the sunset at the end either to settle down with the woman he loves on a small farm far away from trouble or to right wrongs somewhere else. Or, in the case of Shane, to die alone from the gunshot wound he received when he killed the Black Bart character. The hero is courtly to women, no matter how rough and tumble his life has been — those conventions.

Beau L’Amour is an impressive man. He has a masterful capacity to explain his famous father’s life and work without ever getting defensive or losing his objectivity. He works hard to keep all of his father’s novels in print. As he re-releases them, he is adding afterwords that “place” the novel in the larger context of his father’s career. Also, where possible, he shares the back story of its creation, including the diligent research that gives a L’Amour novel its authenticity.

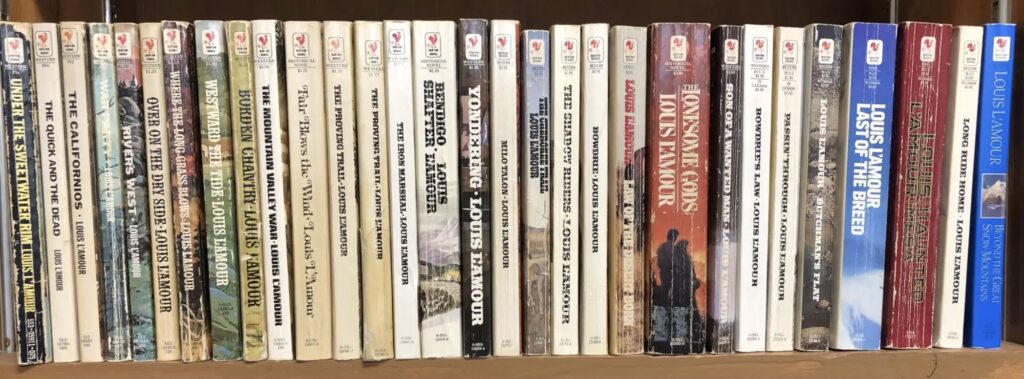

I hadn’t read a L’Amour novel for 20 years or more. Fascinated by the interview, I found a couple in my library and ordered the ones Beau said were among his father’s best. At one time, my mother had all of them lined up on a low top shelf for about 5 linear feet. She started to downsize in her later years. She’d fill a shopping bag with 30 or 40 L’Amour novels and drop them off at the local used bookstore. They were snapped up — by the pound — within days.

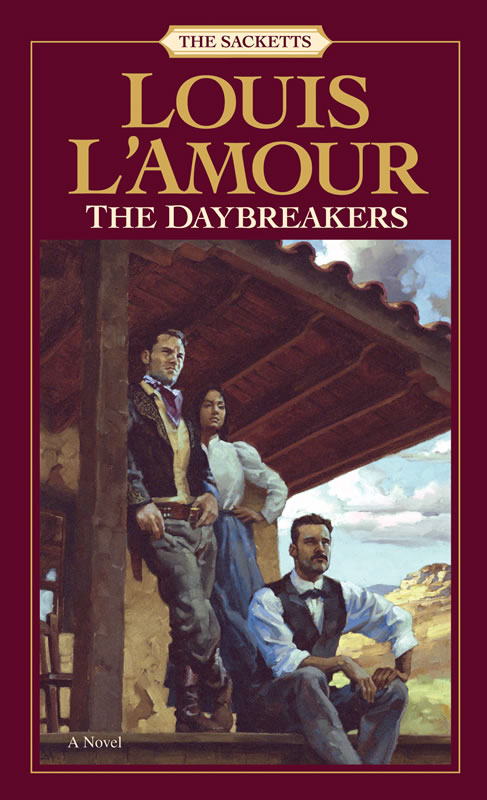

Last night, exhausted from a long day of Listening to America work, I picked up one that had just come in the mail, The Daybreakers. The good thing about L’Amour’s novels is that you can read one in four to five hours. It is four or five days with Jane Austen, and with Joyce or Tolstoy, it is four or five weeks, if you are lucky. When I asked Beau on the podcast which novel he would recommend for those who had never encountered his father’s work, he recommended The Daybreakers, published in 1960. So I read it.

The Daybreakers is the first of the sustained Sacketts series. Eventually, L’Amour published 18 of them. This one is the story of two Sackett brothers, Tyrel and Orrin, who leave troubles behind in Tennessee and head west for a new life and maybe enough prosperity to bring their aging mother to pass her last years on a farm they establish in Colorado or New Mexico. What Ty and Orrin discover, of course, is the lawlessness and violence of the American frontier, including what today we would call the Native American “resistance.” They wind up engaging in a great deal of violence themselves, but the brothers stand for justice, order, and civilization, and they manage to avoid all the evil temptations of unsettled country. Eventually, they do achieve their dream.

In some respects, it feels like “an age too late” for Louis L’Amour. The Daybreakers is 200 pages long, and if I tried to tally up the number of men killed by gunfire in the novel it would come to something like 50. It is not quite one every four pages since there are clusters of mayhem, but there is a wearying amount of gun violence. On the whole, the writing is better than the plot, which is heavily formulaic and filled with clichés about female innocence, Mexican señoritas in shimmering dresses, resource wars (mostly for land and water), and two types of “Indians:” good Indians who accept the dispossession of their homelands and enter into somewhat unequal friendships with white folks; and bad Indians who burn out homesteads and rape and torture their victims.

Western fiction is a genre (somewhat like detective fiction) in which the readers drive the plots and the character types. If a Western did not include some bar fights and shootings, the beleaguered schoolmarm, the wealthy corrupt white man who is attempting to drive small homesteaders (“nesters”) out of the open range, and the sullen gunslinger who would like to break the cycle of violence but can’t, the readership would turn elsewhere. Beau L’Amour said his father, in some ways, was a prisoner of the genre and — in later years — attempted to soften the grip of cowboy and Indian myth with some success.

Louis L’Amour is often a fine writer of English prose. The Daybreakers is told in first person. Here is Tyrel’s first impression of the vastness of the West:

“Suddenly, something had happened to me, and it happened to Orrin, too. The world had burst wide open, and where our narrow valleys had been, our hog-backed ridges, our huddled towns and villages, there was now a world without end or limit. Where our world had been one of a few mountain valleys, it was now as wide as the earth itself, and wider, for where the land ended there was sky, and no end at all to that.”

Reading that made me ache and want to get in my car and light out for the territories ahead of the rest, as Huck Finn puts it.

Here’s a tightly worded assessment of the Western gunfight:

“Nothing exciting or thrilling about a gunfight. She’s a mighty cold proposition for both parties. One or t’other is to be killed or hurt bad, maybe both.”

L’Amour’s immense corpus seldom finds its way into the university curriculum. Professors of literature look down on L’Amour. They dismiss him (and others like him) as hacks, contract men, pulp fictionists, purveyors of bad myths and predictable clichés. Worthy perhaps of a bit of attention in a college course on the pop culture of the mid-20th century or “The Unfortunate Perpetuation of Degrading Myths about Indigenous Culture West of the 100th Meridian,” but beneath the dignity of those who truly care about “lit-ra-chure.”

Fair enough. I don’t think Hondo and The Last of the Breed or The Strong Shall Live qualify as literature if, by literature we mean Jane Austen, George Eliot, James Joyce, Dostoevsky, or even Mark Twain and Fennimore Cooper. Beau told me that his father knocked out four Westerns per year, every year. That means there will be some sloppiness in the prose and plot, and with that sort of screaming deadline hanging over one’s head, reversion to formula is inevitable. Lots of killing. Lots of swinging saloon doors. Lots of visiting ladies from back east staying for a few weeks in the best hotel in the two-year-old town. There are lots of ambushes out among the big rocks where the river cuts a gorge. Death on main street.

And plenty of “Indians.” You won’t see the words “Native American,” “indigenous,” or even “American Indian” in such novels. They were, of course, products of their time. You are more likely to see “Injun” and “sq…w,” “redskin” or “savage.” In The Daybreakers, for example, you find this:

“He rode in silence for a few minutes, then he said, ‘Folks back east do a sight of talkin’ about the noble red man. Well, he’s a mighty fine fighter, I give him that, but ain’t no Injun, unless a Nez Perce, who wouldn’t ride a couple hundred miles for a fight. Folks talk about takin’ land from the Injuns. No Injun ever owned land, no way. He hunted over the country and he was always fightin’ other Injuns just for the right to hunt there.'”

It would take some time to unpack all of this. It certainly reflects the attitude of the majority of white settler colonialists in the post-Civil War period. Thus, L’Amour’s formulations are a valuable window into another time in American history, a darker time. But he wrote these books 60 or more years after the “end of the Indian Wars” at Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation (December 29, 1890). Instead of rethinking the ruthlessness and stereotyping (the Othering) performed by the Anglo conquistadors, such novels perpetuate attitudes that, by 1950, a significant portion of the non-Native public had left behind. If the reader of L’Amour’s novels is nodding at passages like this or telling his buddies at the bar that L’Amour “got it right,” it is hard not to cringe or decry.

L’Amour’s plots are also heavily patriarchal and sexist, and his cowboys like to compare their women to horses, along the “at first, they act purdy skittish but if ya gentle ’em enough” axis. It’s like bad cowboy poetry where you hear much about bipedal “heifers” and “fillies.” And buffalo gals. That doesn’t mean there aren’t some good and strong women in Westerns, including L’Amour’s, but they tend to be the besieged virgin or the widow who now manages the big ranch while shysters and squatters are trying to run her off.

I would have thought that by now this genre would have dried up and blown away “like the dust in the streets of an ole cow town,” but not so Louis L’Amour. Every one of his 100 or so novels is still in print, with more coming thanks to the careful archival work of Beau L’Amour, who is publishing previously unreleased fragments of novels and finishing some of them. Louis L’Amour still sells millions of books annually, now in seven languages. At the height of his fame, it was 27 languages.

The beat goes on. Or the beating goes on.

It’s hard to argue against the market. So far, L’Amour has sold more than 320 million books worldwide. Several score film and TV adaptations. Even now, people want what L’Amour has to sell. Capitalism 101. If he still sells several million copies yearly, he clearly provides something millions want. There are no forced sales. “Serious” writers can sneer at Louis L’Amour, but some of that is pure envy.

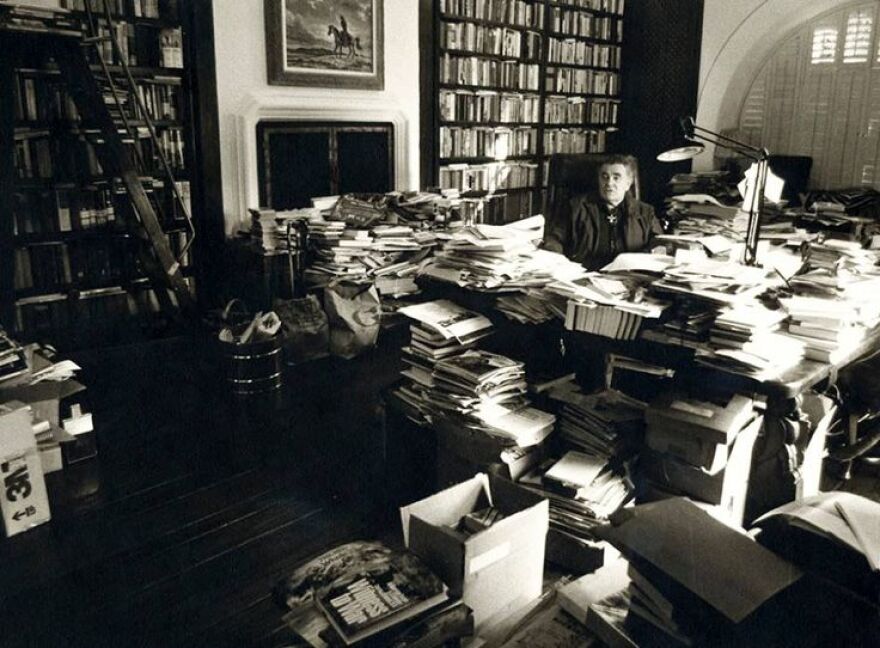

“L’Amour was diligent in his research. He had a vast library. He knew the geography of the places where he set his novels.“

Suppose you want to drift upmarket towards literature. In that case, you can read Larry McMurtry (Lonesome Dove, The Last Picture Show, or Leaving Cheyenne), A.B. Guthrie (The Big Sky), Elmer Kelton (The Time It Never Rained) or Cormac McCarthy (Blood Meridian, All the Pretty Horses). But at the core, they are packaging the same myth of the American West — just with more irony and anti-heroes — and fewer uncomplicated characters.

Remember, Western myth is not without a basis. The frontier was violent. The first settlers got out there before the law arrived, and they had no choice but to settle things extra-judicially. There were horse thieves, holdup gangs, cattle rustlers, remittance men, vigilante groups, sexual predators, cheating gamblers, psychotic killers (Billy the Kid among them), claim jumpers, and more. There were hurdy-gurdy girls in the mining camp saloons, opium dealers, and plenty of people running away from the law back east, social responsibility, violent stepfathers, or debt.

The actual period that spawned our immense Western literature had a short shelf-life. It began after the Civil War, and it was over by the time of the Spanish-American War in 1898. After that, it was dressed up as one of the most tenacious American myths. A significant percentage of L’Amour’s sales now occur in Europe and India (of all places).

One of my old friends, now dead, was a cantankerous but gifted newspaper columnist in Salida, Colorado. He wrote clever anarchical opinion pieces for the Denver Post. But that didn’t entirely pay the bills, so he and his wife knocked out novels for the Trailsman series of grocery store Westerns. (By that standard, Louis L’Amour is Proust!) Before I left town one time, I bought a couple of their books in the local Safeway. My friend explained that there was a formula built into the publishing contract. In the 140 or so pages, there had to be five scenes of graphic western violence and three steamy sex scenes. Sure enough, the trailsman Sky Fargo found trouble wherever he roamed and always got lucky. Thanks to an informal team of ghostwriters, there are many hundreds of Trailsman novels, with names like Six Gun Drive, Montana Maiden, and Condor Pass. I gave a couple to my mother to mess with her romantic obsession but also as a kind of reality check. She knocked them off in an afternoon. She pretended to be a little scandalized. Mostly, I think she was amused.

The more serious classical Western — the Western of Zane Grey, Jack Schaefer, and in Germany Karl May — essentially conformed to formula, too, though in their novels, whatever sex occurred took place well off stage — under the full moon in the boudoir window. Their heroes sometimes engaged in courtship, but consummation had to wait until they put up their holsters and settled down on a small, hardscrabble farm a few miles from a new town somewhere far away.

I do not mean to beat up on Louis L’Amour. In fact, I’d like to convene a big public symposium about his life and work. He’s still, even now, 37 years after his death, one of the top 50 writers in the world for sales.

I do not mean to beat up on Louis L’Amour. In fact, I’d like to convene a big public symposium about his life and work. He’s still, even now, 37 years after his death, one of the top 50 writers in the world for sales. His success is a phenomenon worth better understanding, and his immense appeal deserves serious critical examination. His son Beau is a truly extraordinary man, an excellent representative of his father’s achievement, and he is adding value to the playlist.

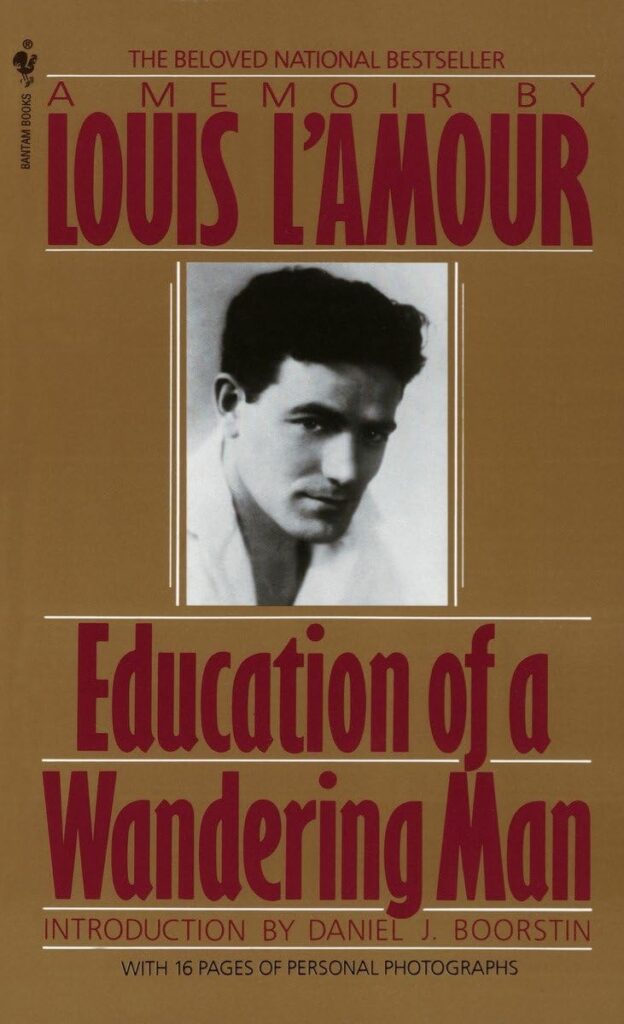

In gathering up some of Louis L’Amour’s work over the last couple of weeks, I’ve discovered that I am still ho-hum about the novels, though they are page-turners! I read one deep into the night and lost some sleep. There is too much violence for my taste (more than the frontier ever actually endured), and the stereotyping of Native Americans in some of the novels is now simply offensive. But I admire L’Amour’s nonfiction. There is not much of it, but his memoir, Education of a Wandering Man, is excellent. I found a big coffee table book in my library that I had forgotten, Louis L’Amour Frontier, text by L’Amour accompanying photographs by one of the West’s best photographers David Muench. Here, for example, is a passage from Frontier that, in some respects, undermines the fixation of his novels:

“The lawlessness in western communities has been much over-rated because of its dramatic aspects. The stories of outlaws and badmen are exciting, and western men themselves still love to relate them. However, over most of the West schools and churches had come with the first settlers, and law accompanied them. The gunfighters and cardsharps were on the wrong side of the tracks, most of them unknown to the general run of the population, although they might be pointed out on occasion.”

Here’s another:

“We are a people born to the frontier. It has been a part of our thinking, waking, and sleeping since men first landed on this continent. The fronter is the line that separates the known from the unknown wherever it may be, and we have a driving need to see what lies beyond. It was this that brought people to America, no matter what excuses they may have given themselves or others.”

In his nonfiction, L’Amour’s treatment of Native people is thoughtful and sympathetic:

“I have walked where the Old Ones walked, and followed paths made by their feet. I have drunk from the springs where they knelt to drink, but I have left no mark of my passing, save what occurs in the pages of what I have written. This was their land; it is now, for the moment, our land. It will someday be the land of those who follow, who in better or worse times must take a living from it or find pleasure in its loneliness, its silence, its beauty. I hope to leave no more mark than the passing of a soft wind, to disturb the sand no more, or bend the grass.”

Amazing. This could have been written by John Muir, Wallace Stegner, or Craig Childs in our time. I wish L’Amour had written more of this. He writes an accessible, straightforward prose. He was diligent in his research. He had a vast library. He knew the geography of the places where he set his novels. Passages such as these clearly indicate that he was a thoughtful man with largely enlightened views. It is unfortunate that the market constricted his gifts and channeled them through a world of formula and, at times, cliché.

I’ve got three more L’Amour novels to read and ordered a book of context and criticism, The Wild West of Louis L’Amour: An Illustrated Companion to the Frontier Fiction of an American Icon by Tim Champlin. I hope to meet the remarkable Beau L’Amour in LA later this year, and I am most eager to read some of his back story afterwords.

And, of course, if my mother were still alive and read this essay (far from certain), she’d say, “Son, you just don’t get it.” She was once a schoolmarm herself.