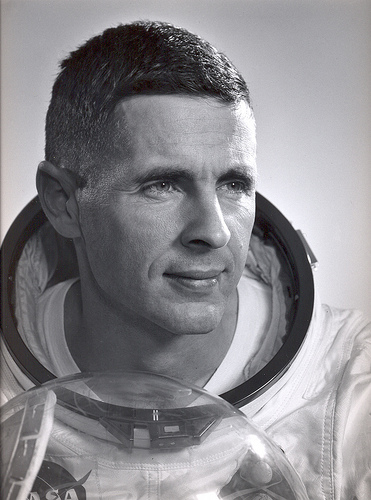

I was saddened to learn of the death (on Friday, June 7, 2024) of the astronaut William Anders, one of the three pilots of the Apollo 8 mission that left “the surly bonds of Earth” and orbited the moon in December 1968. Anders, who was 90, was piloting alone a small plane — a Beechcraft T-34 Mentor — northwest of Seattle when he crashed into Roche Harbor on San Juan Island. The National Transportation Safety Board and the FAA are investigating the accident.

If it were not legacy enough to have been a member of the first space mission that left Earth’s gravity and ventured to another celestial orb, Bill Anders will always be remembered as the man who took the famous Earthrise photograph on Christmas Eve 1968. Earthrise is, by any measure, one of the greatest, most important, and most influential photographs ever taken. It is also possibly the most frequently reproduced photograph in human history.

Apollo 8 is best remembered as the Genesis mission. At the end of a Christmas Eve broadcast from lunar orbit, Anders and mission commander Frank Borman and command module pilot James Lovell read the first verses of the book of Genesis to the people of the Earth: “In the beginning, God created …”

Apollo 8 was arguably the greatest (and most audacious) of all the Apollo missions, even though the three astronauts did not descend to the lunar surface. They were the first humans to blast off on the colossal new Saturn V rocket, which had experienced severe difficulties in its earlier unmanned missions. They were the first humans to fly into deep space. They were the first humans to be captured by another orb’s gravity. They were the first humans to see the far side of the moon. And they were the first humans to witness Earthrise — the sight of the Earth rising over the barren horizon of the moon.

All this happened in one of the most tumultuous years of the 20th century — the year of the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy, the Pueblo incident off the coast of North Korea, LBJ’s surprise decision (March 31) not to stand for re-election, the race riots in scores of America cities, and the cataclysmic Democratic National Convention in Chicago in August. Historian Jeffrey Kluger has called 1968 “a year of sorrow, suffering, and massive bloodshed.”

After Apollo 8 returned safely to earth, Frank Borman received an anonymous telegram that said: “You saved 1968.”

Jim Lovell is still alive. He is 96. Borman died in 2023 in Montana. And now Anders has died in an airplane crash.

Only five of the 26 astronauts who went to the moon between July 1969 and December 1972 are still alive. The moment is coming, and soon, when the last of the lunar explorers will have passed. (See below for full details.) And the last pair of the Beatles cannot be far behind.

The Famous Photograph

The story of the Earthrise photograph is fascinating. Frank Borman was a stern, no-nonsense mission commander on Apollo 8. He did not want to take a newfangled portable video camera on the mission. He considered the telecasts from space as an ill-advised distraction, a Mickey Mouse gimmick. NASA management wanted Apollo 8 to orbit the moon for a sustained period to collect as much data as possible, but Borman forced mission planners to limit the number of orbits to just 10 (20 hours) to reduce the number of things that could go wrong.

Although NASA had prepared a special Christmas dinner for the crew, including a tiny bottle of brandy for each, Borman forbade his colleagues to take a sip. As space historian Andrew Chaikin puts it, Borman “wasn’t about to risk someone in the public raising a ruckus; if they made a single mistake on the rest of the flight, the brandy would get the blame.”

Several times during the journey, Borman rebuked his fellow crew members, particularly Anders, for gazing out the command module’s windows or taking unscheduled photographs. “I don’t want to see you looking out the window!” he barked. When they first entered lunar orbit and saw the moon up close, Anders was filled with a spontaneous sense of wonder. “Oh, my God,” he said, looking down on craters, mountains, rills, and what Buzz Aldrin later called the “magnificent desolation” of the moon. To which Borman replied, “What’s wrong?” Anders said, “Look at that.” To which Borman snapped, “Alright, alright, come on. You’re going to look at that for a long time.”

All business.

But then it happened — at 16:39:39.3 UTC (Coordinated Universal Time), 11:39 p.m. Eastern Standard Time, December 24, 1968.

Chaikin writes:

“Perhaps it is true that our most electrifying experiences are the ones that take us by surprise. Even on the first flight around the moon, in which everything was figured to the second, rehearsed in painstaking detail, an event that no one anticipated became the most moving of all. Apollo 8 was drifting over the far side for the fourth time. Borman prepared to turn the spacecraft so that Lovell would be able to sight the moon through the command module’s sextant.”

Here’s a transcript of what unfolded in the Apollo 8 capsule Christmas Eve:

Anders: Oh my God! Look at that picture over there.

Borman: “What is it?”

Anders: “The Earth coming up. Wow, that’s pretty.”

Even the hard-ass Borman surrendered to the moment. Knowing how stern he had been on the way to the moon, he joked:

“Hey, don’t take that, it’s not scheduled.”

Anders: “You got a color film, Jim [Lovell]? Hand me that roll of color quick, would you?”

Lovell: “Oh man, that’s great.”

They took several photographs with their great Hasselblad 70mm cameras, some in black and white and more in color.

There are two remarkable footnotes to this story. First, it was probably Borman who took the first Earthrise photograph in B&W. As with all such moments in history, there are slightly competing narratives. Second, the actual color photograph was of the Earth “rising” from right to left over the horizon, not from below to above. NASA wisely re-oriented the photo when it was released to the world.

Years later, Anders reflected on the great moment.

“That was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen. Totally unanticipated. Because we were being trained to go to the moon … It wasn’t ‘going to the moon and looking back at the Earth.’ I never even thought about that! In lunar orbit, it occurred to me that, here we are, all the way up there at the moon, and we’re studying this thing, and it’s really the Earth as seen from the moon that’s the most interesting aspect of this flight.”

The Earthrise photograph was immediately celebrated worldwide. The image was printed on the cover of the Spring 1969 issue of the Whole Earth Catalog. Joni Mitchell’s 1976 song Refuge of the Roads includes a verse mentioning the photograph. The U.S. Postal Service released a stamp featuring the Earthrise image in 1969, with the words, “In the beginning God…” printed in italics just above the lunar surface.

The photograph is thought to have helped build international interest in the first Earth Day, celebrated on April 22, 1970. Earth Day first occurred at the end of an incredible decade of environmental legislation in America: the Clean Air Act (1963), the Wilderness Act (1964), the Solid Waste Disposal Act (1965), the Water Quality Act (1965), the Air Quality Act (1967), the National Environmental Policy Act (1969), the Occupational Safety and Health Act (1970) — and then in 1973, the Endangered Species Act.

In addition to all that legislation passed by large bipartisan majorities in a political era very different from our own, Earthrise also helped create what is known as the Overview Effect. The term was coined in the 1980s by author Frank White, who noticed that some astronauts experienced a cognitive shift in their consciousness when they had the opportunity to look back on Earth from deep space. The idea is that when you look back at the entire planet from space, you see landforms but no national borders, the profound beauty (and uniqueness) of the blue, watery planet, its loneliness in the near cosmos, and its fragility. The overview experience invites a fundamental and permanent shift in human consciousness. For example, Apollo 14’s Edgar Mitchell said, “From space, I saw Earth as a precious, fragile ball of life hanging in the void of space, and I became more convinced than ever that we must protect and preserve it.” ISS astronaut Scott Kelly said, “From space, you realize how small and interconnected we all are. It’s a perspective that can inspire us to be better stewards of our planet and work towards a brighter future.” The eminent Carl Sagan, who viewed these images from the Earth, said, “There is perhaps no better a demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world.”

Fair enough, but there is no evidence that the Earthrise photograph has made the world safer and more peaceful. The current big wars in Ukraine and Gaza are as vicious as any in modern history, and as usual, there are little wars and skirmishes across the globe, not to mention a cold civil war heating up in the United States (and France and Britain …). The growing existential menace of Global Climate Change suggests that humans (industrial humankind) have failed to hearken to the visual lesson of the thin and fragile biosphere that makes life possible on Earth. The fact that the United States created a new military branch — the Space Force — in 2019, and geopolitical rivals are beginning to seek dominion on the moon half a century after the U.S.-USSR space race ended makes the Overview Effect seem like a lovely but ineffective phenomenon that has influenced only a tiny, even minuscule, percentage of world leaders or the larger global populations. The world seems more Hobbesian than Saganesque, with no end in sight.

This depressing failure of human imagination does not diminish William Anders’s great achievement, but it does make one ask: If Earthrise cannot lift humanity to a higher order of enlightenment, what will?

The Life of William Anders

Anders was born in Hong Kong on October 17, 1933, the son of a U.S. naval lieutenant. Anders and his mother had to flee China when the Japanese attacked Nanjing in 1937. He graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1955, but he obtained a commission in the U.S. Air Force instead because he wanted to fly airplanes. He served as a radiation expert and a fighter pilot tracking Soviet heavy bombers that approached America’s air defense perimeter. He received a master’s degree in nuclear engineering from the Air Force Institute of Technology in 1962. Although he had never been a test pilot, he was inducted into the third class of American astronauts in 1964. He flew into outer space just once, but without having set out to do so, he took one of the world’s great photographs.

Anders retired from the Air Force in 1969 and accepted a National Aeronautics and Space Council position. Later, he became a member of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), chaired the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and served as the American ambassador to Norway. After that, he accepted executive posts with defense and space contractors. Anders and his wife Valerie established a flight museum in Seattle in 1996.

The Status of America’s Lunar Astronauts Today

A total of 26 men (all American astronauts) have been to the moon. Just five are still alive.

Twelve men set foot on the moon. Six others stayed back in the Command Module. Of the 12 moonwalkers, eight are dead, and four still alive:

The dead include Apollo 11’s Neil Armstrong (2012); Apollo 12’s Pete Conrad (1999) and Alan Bean (2018); Apollo 14’s Alan Shepard (1998) and Edgar Mitchell (2016); Apollo 15’s James Irwin (1991); Apollo 16’s John Young (2018); and Apollo 17’s Gene Cernan (2017).

Still alive are Apollo 11’s Buzz Aldrin, Apollo 15’s David Scott, Apollo 16’s Charles Duke, and Apollo 17’s Harrison Schmitt (whom I’ve met).

Bill Anders was one of the 14 astronauts who orbited the moon but did not land. The same was true of the other two crewmembers of Apollo 8 and all three of Apollo 10 and Apollo 13, plus the six command module pilots who stayed in orbit during Apollo 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, and 17. Of those 14 astronauts, only one is still alive: Jim Lovell.

Three astronauts flew to the moon twice. Jim Lovell (still alive); Eugene Cernan (2017); and John Young (2018). Of these three, only Cernan and Young have stepped on the moon. Poor Lovell: he achieved some fame as one of the three astronauts on the Apollo 8 Genesis mission in 1968, then much more as the commander of the aborted Apollo 13 in April 1970 (“Houston, we have a problem”), but he never left a footprint on the moon. Fifty years later, he said he no longer felt any regret: “To me, this was a real adventure. It was like a mini Lewis and Clark expedition. I wasn’t there to beat the Russians, I didn’t really care if we beat the Russians or not. I was there because we were exploring new ground, new territory.”

Gene Cernan was the last man on the moon. He climbed back up the ladder of the Lunar Excursion Module at 11:34 p.m. on December 14, 1972. Before he made the climb, he said, “As I take man’s last steps from the surface, back home for some time to come — but we believe not too long into the future, I believe history will record that America’s challenge of today has forged man’s destiny of tomorrow. And as we leave the moon at Taurus-Littrow, we leave as we came, and, God willing, as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind. … Godspeed the crew of Apollo 17.”

For Further Reading:

Jeffrey Kluger. Apollo 8: The Thrilling Story of the First Mission to the Moon.

Robert Kurson. Rocket Men: The Daring Odyssey of Apollo 8 and the Astronauts Who Made Man’s First Journey to the Moon.

*Andrew Chaikin. A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts.

Frank White. The Overview Effect: Space Exploration and Human Evolution.

Robert Poole. Earthrise: How Man First Saw the Earth.

Craig Nelson. Rocket Men: The Epic Story of the First Men on the Moon.

*If you only have time for one!