As Clay prepares for the second leg of his Travels with Charley journey, Russ Eagle offers suggestions on John Steinbeck biographies for those interested in knowing more about the author.

Though Steinbeck took deliberate steps to trip up future biographers, the fruits of their labors have served his reputation well in the half-century since his death.

John Steinbeck abhorred publicity of any kind. Even after struggling for seven years early in his career while earning less than $900, he resisted his publishers when they sought biographical material for publicity purposes. “Unless I can stand in a crowd without any self-consciousness and watch things from an uneditorialized point of view,” he said, “I’m going to have a hell of a hard time.” As late as Travels with Charley (1961), he was still lamenting readers who were “more interested in what I wear than in what I think.” Though he mellowed a bit with age — Steinbeck even supplied a physical description of himself early in Travels with Charley — he never backed down from this stance. He made conscious efforts to discourage and dissuade future biographers, burning caches of letters and manuscripts and subtly sustaining the perpetuation of various biographical falsehoods.

Two things hampered Steinbeck’s efforts. First of all, he was a prolific letter writer, sometimes six or seven in a single day — and many people saved his letters, both before and after he became famous. Thousands survive, many packed with details that Steinbeck would have preferred to keep private. Second, Steinbeck died young at age 66. He was survived by his wife Elaine, two ex-wives, two sons, two sisters, numerous friends and acquaintances, literary contemporaries, and more. A lot of people with a lot to say about Steinbeck outlived the writer by decades. He had, he realized, “left a lot of tracks.”

Despite Steinbeck’s fears, those tracks have been kind to him in the 56 years since his death. Both he and his work have been the subject of many well-written and insightful biographical and critical works, and these volumes have gone a long way toward rehabilitating a faded literary reputation. In terms of straight biographies, the following are excellent resources for anyone wanting to know more about Steinbeck. All are either still in print or easily obtainable on used book sites.

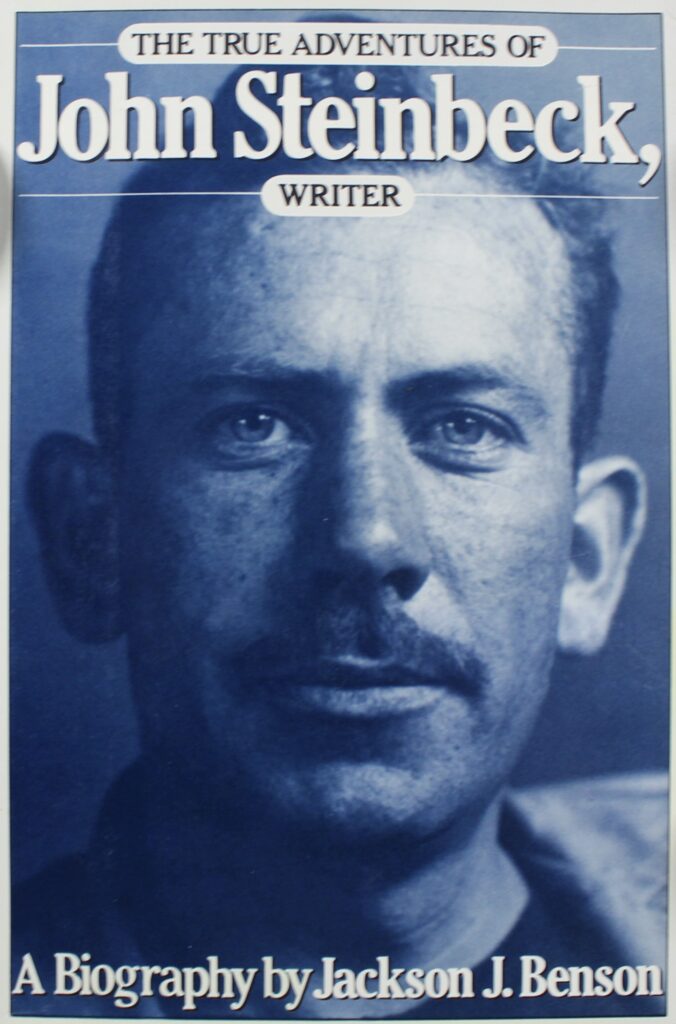

The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer

By Jackson Benson (Viking Press, 1984)

Now in paperback as John Steinbeck, Writer

This is the definitive Steinbeck biography, the heavyweight, literally and figuratively. Benson was a young professor looking to write a short critical work when, thanks to a chance meeting with Steinbeck’s sister, he found himself knighted by the Steinbeck estate as the authorized biographer. Twelve years of research and three years of writing resulted in a massive work of over 1,000 pages loaded with detail. Though Benson passed away in 2023, his name will always be spoken with reverence in Steinbeck circles. His research is now housed in Special Collections at Stanford University where it will remain a treasured resource for decades to come.

“This is the story of a man who was a writer. He cared about language, and he cared about people. He didn’t want to be famous or popular — he just wanted to write books. But he became both. From among the many serious writers of our time, he became for a great many people, here and throughout the world, the one writer who counted, the one who touched them. He made words sing, and he made people laugh and cry. He also made them think — about loneliness, self-deception, and injustice. And in all that he wrote, he testified to his belief that everything that lives is holy.”Jackson Benson, preface to The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer

A few years later Benson published a second title, Looking for Steinbeck’s Ghost (University of Oklahoma Press, 1988). This is the narrative of his 15-year journey, but it also retells Steinbeck’s story in an unconventional and non-chronological fashion. If you’re not ready to take on 1,000 pages, Looking for Steinbeck’s Ghost provides a shorter, quirkier introduction to his life while also detailing the challenges and struggles of a biographer.

Steinbeck: A Life in Letters

Edited by Elaine Steinbeck and Robert Wallsten (Viking Press, 1975)

Elaine Steinbeck outlived her husband by 35 years, a period she devoted to protecting and promoting his legacy. In 1975, realizing that Benson’s work was still years from completion, she spearheaded this publication of more than 850 of Steinbeck’s letters. Presented chronologically, its editors refer to it as “not only a selection of letters, but a biography of letters.” Read cover to cover, these dispatches do intimately retell Steinbeck’s story. But this volume also lends itself to jumping around. Some of Steinbeck’s best writing can be found in his letters and journals.

“I have your letter today. And I am sorry but I cannot change that ending. It is casual — there is no fruity climax, it is not more important than any other part of the book — if there is a symbol, it is a survival symbol not a love symbol, it must be an accident, it must be a stranger, and it must be quick. To build this stranger into the structure of the book would be to warp the whole meaning of the book … The incident of the earth mother feeding by the breast is older than literature. You know that I have never been touchy about changes, but have too many thousands of hours on this book, every incident has been too carefully chosen and its weight judged and fitted. The balance is there. One other thing — I’m not writing a satisfying story. I’ve done my damndest to rip a reader’s nerves to rags, I don’t want him satisfied.”

Steinbeck to editor, Pascal Covici after being asked to consider changing the end of The Grapes of Wrath.

A Life in Letters

Imposing as this collection is, its editors omitted nearly 4,000 letters. Hundreds of others exist as well in private and institutional collections. Robert DeMott, the dean of Steinbeck scholars, has opined that a complete and generously edited and annotated collection of Steinbeck’s letters and journals remains the great missing link in Steinbeck scholarship.

John Steinbeck: A Biography

Jay Parini (Henry Holt and Company 1995)

Jay Parini is a poet, novelist, biographer, screenwriter, and critic. In the early 1990s, less than a decade after the publication of Benson’s magnum opus, Elaine Steinbeck convinced Parini to produce this volume. Parini admits in his preface that Steinbeck’s widow “assisted me throughout the writing of this book.” At less than 500 pages, it is less intimidating and more accessible than Benson. Interlacing Steinbeck’s personal story with his literary development, Parini argues that Steinbeck was a major novelist who never deserved the critical disdain he received from the Eastern literary establishment. He describes Steinbeck as “a uniquely authentic writer who, over nearly four decades, produced a body of work that evokes life in this century with compassion and lyrical precision.”

Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck

William Souder (W.W. Norton & Company, 2020)

This most recent biographic work on Steinbeck came from an outsider of sorts. William Souder was attracted to Steinbeck after completing award-winning works on John James Audubon and Rachel Carson, loners who, like Steinbeck, were fascinated by the natural world. Unlike Benson, who argued that Steinbeck’s work grew out of care and curiosity about people, Souder was convinced that Steinbeck’s art sprang from rage — rage against poverty and injustice and prejudice, against the strong preying on the weak, against ex-wives and literary critics. He attributes Steinbeck’s “sour response to the world around him” as evidence of a recurring depression. Souder’s account is well-written and readable, and it presents a fresh perspective on Steinbeck and his work from a 21st-century perspective. Souder tells Steinbeck’s story at a brisker pace than his predecessors; Mad at the World comes in at just over 350 pages.

“Before his second birthday, Wilbur and Orville Wright would fly. And within months of his death, Neil Armstrong would walk on the moon. In between, John Steinbeck tried to tell the story every writer hopes to get right, which is only how it was during one small chapter of history. It is not much to ask, but the hardest thing on earth to do.”

William Souder, Mad at the World

Part II of this article will include additional biographical works on Steinbeck that concentrate on specific periods and relationships in his life, including his first wife Carol, his good friend Ed Ricketts, and his editor Pat Covici.