I have been reading Hampton Sides’ excellent new study of Captain James Cook’s third voyage (1776-1779), The Wide, Wide Sea: Imperial Ambition, First Contact, and The Fateful Final Voyage of Captain James Cook. Just to make things interesting, I have at the same time been re-reading Tony Horwitz’s sparkling Blue Latitudes (2002), and I’ve been feverishly texting my friend David Nicandri, whose study of the third voyage, Captain Cook Rediscovered: Voyaging to the Icy Latitudes, challenged much of the received tradition about that fatal voyage, which left Cook dead on the big island of Hawaii.

The challenge of writing a book about Captain James Cook (1728-1779) in the 21st century is that we have decided that there is so much to deplore. I can summarize in seven words: imperialism, exploitation, objectification, colonialism, extraction, Eurocentrism, destabilization. And yet the story of Cook’s three circumnavigations of the Earth is so utterly fascinating, so chock full of amazing, at times astounding, incidents, so enriched by discoveries (European discoveries, that is) and First Encounters, so enlivened by exoticism, and an unavoidable sense of wonder at the sheer audacity of Cook’s achievements, that it is hard to maintain a frown of moral righteousness, even though we all agree that Cook’s voyages raise serious questions about the Age of Discovery.

One of the best things written about European exploration came long before postcolonialism or postmodernism. Alan Moorhead, in his 1966 book The Fatal Impact, wrote of “the fateful moment when a social capsule is broken open.” It’s a perfect metaphor. A banana holds up well as long as you don’t peel it. The minute you peel it, it starts to rot. This is true of an egg, too. How many accounts do we have of first encounters with people living in what Europeans regard as a natural, Edenic state, followed by the debasement of that indigenous culture?

Almost every honest journal keeper or correspondent in the history of Anglo-American exploration took time to admit that contact between Europeans and indigenous people was inherently disruptive and that the representatives of the “superior” civilization were seldom exemplars of the better traits of their home nations. When Lewis and Clark neared the Pacific Ocean from the interior in late 1805, they observed the degrading effect of previous white contact in the lower Columbia River. The Natives had STDs. One woman had the proprietary tattoo “J. Bowman” on her arm. The Natives were insolent in trade. A coastal man knew this much English: “son of a pitch.”

“In Cook’s long wake,” Hampton Sides writes in the preface to The Wide, Wide Sea, “came the occupiers, the guns, the pathogens, the alcohol, the problem of money, the whalers, the furriers, the seal hunters, the plantation owners, the missionaries.”

The Risk of First (and Subsequent) Contact

Hawaiian Natives murdered James Cook on February 14, 1779. His untimely death on Valentine’s Day was unfortunate, but as they said of Elvis, it was a great career move. While on duty for his majesty George III at a far corner of the world, his martyrdom has lifted him to tragic grandeur. Had he returned safely to England at the end of the 1770s and retired with honors to a well-deserved private life, he would not command as much worldwide attention as his martyrdom evokes. Sides tells the last 10 minutes of Cook’s life with a lovely sense of slow motion — and inevitability. It is, by any measure, one of the most famous moments in the history of exploration.

The essence of exploration is the moment when the explorer hands his firearm to a subaltern, rolls up his sleeves, and walks forward slowly, alone, and with evident friendliness toward a cluster of people who have never or seldom seen a white person before. He cannot know whether he will be killed or caressed, become a national statistic or be treated to the “national hug,” as Meriwether Lewis derisively called the fulsome welcome he received from the Shoshone leader Cameahwait on August 11, 1805. Lewis performed this full ritual only once in the 28-month journey he undertook on behalf of President Jefferson. It makes for some of the most compelling prose in the expedition’s journals. Cook did Full First Contact countless times, often in situations where it could not be known whether he would be embraced or disemboweled.

All of these explorers complained that the Indigenes were capricious, erratic, irrational, coy, and evasive. On August 15, 1805, just inside Idaho, Lewis was terrified that the band of Shoshone he had encountered and with whom he was now camping would slip away in the night before he could obtain the horses the expedition needed to cross the Bitterroot Mountains. He acknowledged that the Shoshone were themselves concerned that he was trying to lead them into an ambush. Still, their capriciousness caused him to lose sleep: “I slept but little as might be well expected, my mind dwelling on the state of the expedition which I have ever held in equal estimation with my own existence, and the fait of which appeared at this moment to depend in a great measure upon the caprice of a few savages who are ever as fickle as the wind.” James Cook could have easily written this sentence, though the British mariner was less likely to reveal his emotions than Lewis.

The Tired Captain Cook Paradigm

I’m not a student of Captain Cook historiography, but at some point historians, led by the dean of Cook studies, J.C. Beaglehole, determined that Cook was worn out by the time he undertook his last voyage, that he was spiritually diminished, increasingly inflexible, that his judgment was not what it once was, that his heart wasn’t really in the last of his voyages, that his temper was hotter and more often expressed.

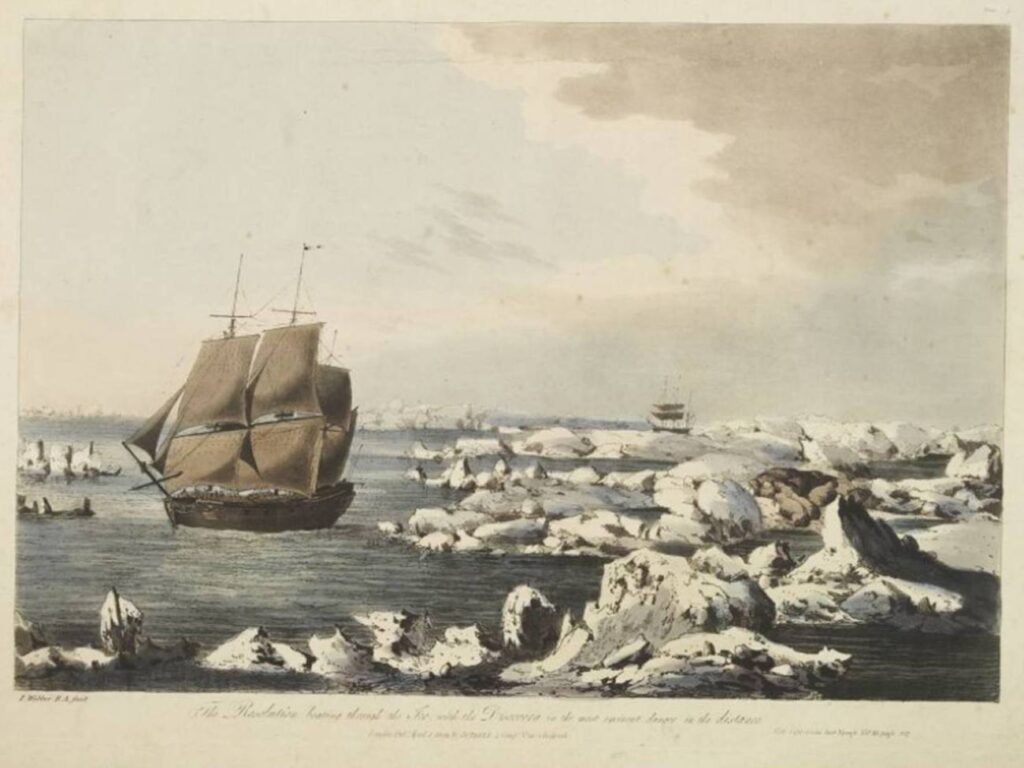

I don’t know enough to know for sure whether this is true — nobody knows for sure — but I don’t see it. On the third voyage, Cook dutifully returned Mai (Omai the Tahitian) from London to the Society Islands, a journey of 20,000 miles from the mouth of the Thames, before he undertook the true mission the British Admiralty had handed him. Only then, on December 7, 1777, did Cook begin his journey along the western coast of North America in search of the fabled Northwest Passage. This time, the search for the elusive passage would be undertaken from the top of the west coast of North America to the east. You cannot read any account of this phase of the voyage without gaining a deep respect for Cook, who had been led to believe that Alaska’s western coast was not much west of San Francisco, just farther north, but who soon learned that what stood between him and the top of North America was the immense western-stretching peninsula of Alaska! Undaunted, Cook explored the entire southern and west coast of Alaska, all the way out to the middle of the endless Aleutian Islands, before he found a wide enough gap to thread his two ships up to the top of Alaska. Along the way, he made a detailed survey of Prince William Sound and the Cook Inlet. Once through the frustrating Aleutians, Cook explored Bristol Bay, Kuskokwim Bay, and Norton Sound before finally passing through the Bering Strait and on to a place near the top of Alaska he named Icy Cape. That’s when a solid wall of ice forced him to turn back.

Before Cook, no European or Russian had understood how massive Alaska was or how far west its mainland stretched (even before the endlessness of the Aleutians). Before Cook, no one was sure that Alaska was not an island. Cook settled all of that geography once and for all. He did not find the Northwest Passage, which then did not exist and, practically speaking, doesn’t now, despite global warming. By the time winter weather forced Cook to turn his little fleet south towards Hawaii (the Sandwich Islands), he had pretty well satisfied himself that there was no shortcut across the continent at high latitudes, no matter from which direction you started. And yet, he planned to overwinter in Hawaii where he could repair his ships, find healthy food, and give his weary, lonely, homesick men some R&R, including of course, sexual R&R, and then return to Alaska earlier the following summer, beginning farther west, no longer diverted by the allurement of the various bays and sounds he once thought might be transcontinental inlets. In other words, he decided to add another full year to his travels to settle a point of global geography! He was determined to return to the high Arctic and, this time, ascertain once and for all whether it was possible to sail from the Pacific to the Atlantic over the top of the North American continent. Having already essentially concluded that there was no such passage, he nevertheless determined not to sail home to England until he had settled the question. It’s hard to imagine any other explorer spending another year on the other side of the world on the slender possibility that he might find the fabled throughway a little farther north.

This does not sound to me like a tired and spent mariner. His survey of the coastal contours of Alaska was dangerous: perpetual fog so thick that crewmen could not see the front end of the ships; hidden, undiscovered, and therefore uncharted reefs and rocks; the encroaching ice of the northern ice fields; loss of contact with the other vessel and fear that they would collide in the pea soup fog; increasing fear and anxiety among the ship personnel; increasingly poor health among the frostbitten crew; rancid foodstuffs; damaged and leaky ships.

It is also often alleged that it was the spiritually exhausted Cook who got himself killed at Kealakekua Bay in Hawaii, that the younger Cook of the previous voyages would not have let that situation get out of hand, would not have precipitated the violence of that fatal day by shooting an indigenous man at close range for seeming to menace him.

Well, maybe. However, as Sides tells the story of February 14, 1779, the unfolding events feel inevitable. The British visitors had worn out their welcome. It was expensive hosting sex-starved, produce-starved, wood-devouring strangers. Cook left the Hawaiian islands safely enough on February 4, but when he was forced to return to Kealakekua Bay nine days later after rough seas damaged the Resolution’s foremast, the mood of the natives was now decidedly hostile. If Cook had previously let himself believe that the Natives regarded him as a divine or semi-divine figure (Lono), he was about to confirm that he was “human all too human.” Once the aura of invincibility and perhaps divinity fissured, the Hawaiians spent what must have been a deep fund of rage and frustration at the high-handed ways of these aggressive visitors.

It is relatively hard to see how the fatal day could have ended peacefully once Cook stormed ashore intending to take the king of the island Kalaniʻōpuʻu-a-Kaiamamao a hostage until the expedition’s cutter boat was returned by the Natives who stole it. He was determined to make an immediate, firm, and unambiguous show of force. He and his marines were heavily armed. Appearing on someone else’s shore as they did in what could only be regarded by the Natives as an aggressive posture, he necessitated a formidable response. A resistance. Mark Twain, visiting the Kealakekua Bay in 1866 and making some inquiries, pronounced Cook’s death “justifiable homicide.” The captain of Cook’s sister ship, Discovery, Charles Clerke, concluded, “Upon the whole, I firmly believe matters would not have been carried to the extremities they were had not Captain Cook attempted to chastise a man in the midst of this multitude.”

Cook’s sense of urgency is understandable. He knew that the cutter was almost certainly stolen so that Natives could strip it of all of its metal, which was infinitely more valuable to them than the watercraft, inferior to their boats in every way, including aesthetically. So Cook decided to take the king hostage, hoping the thieves would be pressured to return the boat before it was broken up. This method of coercion had worked before on other Pacific islands. Cook felt a pressing need to resume his reconnaissance of Alaska and his final search for the Northwest Passage. He knew the narrow window of weeks that the higher latitudes would be seasonally ice-free. After watching the advent of Arctic winter curtal the previous year’s search, he knew he needed every temperate day of 1778 to fulfill his mission. Cook could brook no sustained play of diplomatic intercourse, waiting days or weeks to recover the cutter, which would undoubtedly have perished in the interim. He may not have been emotionally exhausted in February 1779, but it is clear that he was emotionally done with the Hawaiians, at least for the rest of that exploration season.

By the time of his untimely death, Cook was 50 years old. He had spent much of his adult life at sea, leading three of human history’s most audacious sea voyages. He may not have been spiritually exhausted, but by this time, he had undoubtedly become jaded and weary of the often-inexplicable rituals of indigenous hospitality and reaction wherever he chose to land. The anthropologist Cook never stopped observing Native ways, but the British sea captain, a fellow of the Royal Society, must have longed for some predictable rites of English civility.

The Excellence of Hampton Sides

The best of Sides’ book is the last third, after New Zealand, Tahiti, and the Hawaiian Islands. That’s when the true mission began, and Cook exhibited his renowned drive and perseverance. There is a fascinating irony here. Until very recently, historians have given short shrift to Cook’s third voyage explorations of the high latitudes of the North and fixated on what my friend David Nicandri calls the “Polynesian Paradigm” — topless copper-skinned Native women seemingly eager to bed visiting Europeans. Plus breadfruit.

Captain Cook and the Republic of Letters

Until now, my favorite Cook story was his 1769 voyage to the island of Tahiti to observe the rare Transit of Venus (1761 and 1769). That’s a story straight out of the Enlightenment. The best book on the transit is Andrea Wulf’s 2012 Chasing Venus: The Race to Measure the Heavens. Cook made that immense journey when France and Britain were locked in global conflict, and the 13 American colonies began asserting their independence. Benjamin Franklin, America’s great exemplar of the Enlightenment, exerted himself diplomatically to exempt Cook from any military engagement on the high seas. Cook’s scientific importance was so great that he must be exempted from any geopolitical harassment on the high seas. Should Cook’s vessel “happen to fall into your hands,” Franklin wrote to the European diplomatic corps, “you should not consider her as an enemy, nor suffer any plunder to be made of the effects contained in her, nor obstruct her immediate return to England.” This is perhaps the single finest example of what is meant by the term Republic of Letters, the community of like-minded, high-minded scientists, reformers, scholars, and men of letters of all European nationalities who corresponded freely and looked out for each other in their attempt to solve mysteries and “ameliorate the condition of mankind,” as Jefferson put it.

The Greatness of James Cook

Wherever he ventured, but especially among people with no previous contact with European “civilization,” Cook did what he could to prevent his men from infecting Native women with STDs. However, at times it proved to be nearly impossible. He urged his lieutenants to tolerate the small liberties and minor pilfering of the Natives, understanding that the two cultures saw such concepts as “property” and “theft” differently. When he was aware that he was making first contact with a Native people, he tried hard not to discharge any firearms on their shores. On one such occasion, Cook wrote, “We had the good fortune to leave them as ignorant of firearms as we found them. They never saw, nor heard, a musket fired.” Cook was always concerned with the health and well-being of the men who sailed with him. He experimented with various antiscorbutics (foods that countered the bane of the Age of Sail, scurvy). He insisted on a tight regimen of hygiene and cleanliness on his ships that differentiated him from most sea captions of his era. He worked hard to understand the sometimes bewildering ways of the Indigenous people he met and usually observed and noted rather than judged Native rites. For a man born in a mud-walled house in Yorkshire, Cook mastered navigation, cartography, and the discipline of precise and unfailing record keeping — something Meriwether Lewis, under much less difficult travel conditions, could not achieve. He worked hard to maintain discipline on his ships — he was not averse to the whip — but he was not a sadist like William Bligh. As “exemplars of imperialism” go, James Cook was among the most enlightened in every way.

I highly recommend The Wide, Wide Sea: Imperial Ambition, First Contact, and The Fateful Final Voyage of Captain James Cook. But I think you’ll enjoy it even more if you spend some time with Horowitz’s Blue Latitudes, too.