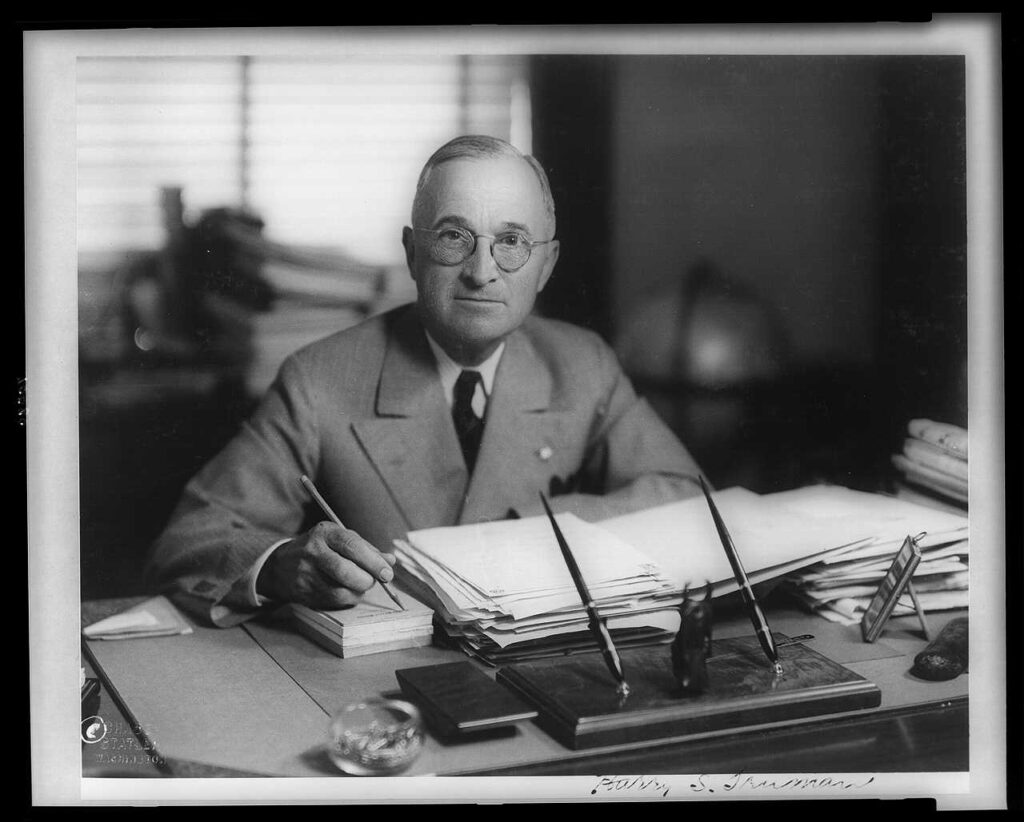

With the death of Franklin Roosevelt on April 12, 1945, Harry S. Truman became one of the nation’s most unlikely presidents. Truman, with little preparation, was thrust into the presidency amid the most tumultuous four months in world history.

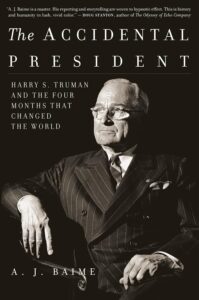

I recently read A.J. Baime’s The Accidental President: Harry S. Truman and the Four Months that Changed the World. I haven’t read Baime’s other books, but I will. He is a very good writer.

Here are a couple of examples:

“As the world awaited news of peace, the atomic bomb loomed over the public consciousness. Citizens in every civilized country struggled to understand what the bomb was, how it worked, and what it meant for the future of humanity.”

About Truman sailing home on the USS Augusta on the day Hiroshima was bombed:

“After breakfast, Truman relaxed on the deck and listened to the ship’s band play a concert, unaware at this moment that Hiroshima had been all but wiped off the planet.”

One more:

“History does not definitely record the day when Truman realized that he would soon face the most controversial decision that any president had ever faced, and perhaps would ever face, in all of time. But evidence suggests that the first of June [1945] was that day.”

When history is written by a talented prose stylist, it is much more pleasurable to read, so long as it doesn’t sacrifice accuracy and nuance for the sake of readability. It was Theodore Roosevelt, himself an excellent writer, who made the case for well-written history in his address to the American Historical Association on December 27, 1912, just weeks after he lost the 1912 presidential election:

“The imaginative power demanded for a great historian is different from that demanded for a great poet; but it is no less marked. Such imaginative power is in no sense incompatible with minute accuracy. On the contrary, very accurate, very real and vivid, presentation of the past, can come only from one in whom the imaginative gift is strong. The industrious collector of dead facts bears to such a man precisely the relation that a photographer bears to Rembrandt.”

I’ve read several good books on Truman over the years, but none so good as this. It should be noted, however, that Baime concentrates on the four-month period between April 12, 1945, and September 2, 1945, when Japan formally surrendered. We get some flashbacks to Truman’s years in the Senate and his problematic initiation into politics as the darling of the corrupt Pendergast Machine in Kansas City, but very little on the post-presidential years. Baime has another Truman book, Dewey Defeats Truman: The 1948 Election and the Battle for America’s Soul, which presumably takes us through Truman’s re-election and deeply unsatisfying second term. I’ve ordered it!

Accidental President

Harry S. Truman was indeed an accidental president (like Theodore Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson, though Roosevelt would almost certainly have found a way to get himself into the White House no matter what!). Truman did not want to be nominated as FDR’s running mate in 1944. He knew that FDR was nearing death and would almost certainly not finish out his fourth term, and he did not consider himself presidential material. FDR’s closest aides (and the president himself) knew that he was dying during the winter and spring of 1944-45. It’s inexplicable, therefore, that the president and the Democrats did not choose a running mate who was reasonably ready to assume the office.

Truman had had virtually no contact with President Roosevelt before or after the election of 1944. As most people know, Truman was told of the Manhattan Project and the work of Hanford, Oakridge, and Los Alamos just hours after he took the oath of office on the afternoon of April 12, 1945. The learning curve, including the moral learning curve, was straight up.

The first four months of Truman’s presidency were some of the most important months of the 20th century. FDR did not live to know of the execution of Mussolini, the suicide of Hitler, the end of the war in Europe, the Russian bombardment and capture of Berlin, the continued U.S. firebombing of Tokyo, the hardening of the USSR’s position on post-war questions, or the successful first test of the atomic bomb in New Mexico. Truman immediately realized that he was not ready to take on such momentous burdens. He had not been briefed on any of the key issues in the 82 days he served as vice president. But he recognized that fate had put him into the most important chair in the world at one of the most critical moments in history, and that he had better buck up and face his burdens with clarity and courage.

Above all, within weeks of assuming the presidency, Truman had to decide whether to use the atomic bomb and, if so, where. He was no nuclear scientist, and he had nothing more than a high school education, but Truman knew that he would be authorizing the killing of tens of thousands of Japanese citizens who were no more responsible for the war than the people of his hometown in Independence, Missouri.

In the 27 years of his life following Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Truman never expressed regret that he had made the decision to use the bomb to end the war. His view was that if he saved American (and Japanese) lives by using the device, he had made the right — and only politically acceptable — decision. He famously threw Oppenheimer out of his office when the great and cerebral scientist blurted out that he, Oppenheimer, had blood on his hands. “Don’t you bring that fellow around again,” Truman barked. “After all, all he did was make the bomb. I’m the guy who fired it off.” The Buck Stops Here, indeed.

Character Matters

Truman had integrity. At Potsdam an unnamed U.S. army colonel offered to find the president a bed partner if he wished it. As the defeated German people stared in the face of starvation and homelessness, many German women offered their bodies to the occupiers in exchange for food and shelter or even a pack of cigarettes. “Listen, I know you’re alone over here,” the officer said. “If you need anything like, you know, I’ll be glad to arrange it for you.” Truman was appalled. “Hold it: don’t say anything more. I love my wife, and my wife is my sweetheart. I don’t want to do that kind of stuff. I don’t want you to ever say that again to me.”

Truman was a devoted family man. After Washington Post music critic Paul Hume wrote an unrelentingly (but accurate) critical review of first daughter Margaret Truman’s singing performance at Constitution Hall, the president of the United States held nothing back. On White House stationary he wrote, “It seems to me that you are a frustrated old man who wishes he could have been successful. When you write such poppy-cock as was in the back section of the paper you work for it shows conclusively that you’re off the beam and at least four of your ulcers are at work. Someday I hope to meet you. When that happens, you’ll need a new nose, a lot of beefsteak for black eyes, and perhaps a supporter below!” Truman and George Washington had at least one thing in common: difficult mothers. Truman was unendingly patient with his mother, who was, among other things, outspoken in her view that the South should have won the Civil War. She refused to sleep in the Lincoln Bedroom at the White House, even when she was informed that Lincoln never slept there.

Truman’s essential modesty is admirable and by today’s standards of political bloviation astounding. After he announced to the American public the end of the war in the Pacific, he wrote immediately to former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt: “I told her that in this hour of triumph I wished that it had been President Roosevelt, and not I, who had given the message to our people.”

The day after he learned of FDR’s death and his sudden ascension to the presidency, Truman said to reporters, “I don’t know whether you fellows ever had a load of hay fall on you, but when they told me yesterday what had happened, I felt like the moon, the stars, and all the planets had fallen on me.”

During the Potsdam Conference of the Big Three in July 1945, President Truman drove around the German countryside with General Eisenhower. Years later, Eisenhower remembered, “Now, in the car, he suddenly turned toward me and said, ‘General, there is nothing that you may want that I won’t try to help you get. That definitely and specifically includes the presidency in 1948.’” Eisenhower hasted to inform the president that he would not be running for the presidency in 1948.

Most important, Truman understood how difficult the presidency was likely to be, particularly in following the great and legendary Franklin Delano Roosevelt into the Oval Office. When on April 12, 1945, Eleanor Roosevelt in her White House study told Truman her husband was dead, “You can understand how I felt at that moment,” he remembered. “It was necessary for me to assume a greater burden, I think, than any man has assumed in the history of the world.” Hitler was not yet dead. The war in Europe was expected to continue through the end of the year, the war against Japan to last another 18 months, with an American body count likely to reach the hundreds of thousands, if not millions. Even if the U.S. could bring the war to conclusion, the challenges the next president would have to face in the post-war world were possibly beyond the capacity even of FDR.

After the failures of the Potsdam Conference — in which Stalin made it clear that he would not fulfill his promises to let Eastern bloc countries hold democratic elections or chart their own destiny — Truman thought of resigning the presidency. He believed he had failed the American people. He knew the Second World War had begun over the question of Poland’s sovereignty and territorial integrity; now Truman and Churchill (and Clement Atlee) had to accept Russia’s hegemony in Eastern Europe, because the only alternative was World War III.

An Amazing Cast of Characters

Baime’s Accidental President provides profiles of some of the other larger-than-life figures of that era, including Winston Churchill, the U.S. ambassador to the USSR Averell Harriman, Justice Robert H. Jackson of the Supreme Court, Eleanor Roosevelt, Edward R. Murrow, Curtis LeMay, George Marshall, and Dwight Eisenhower.

The most interesting of these extraordinary men and women was Henry Stimson (1867-1950). I have long been an admirer of Stimson, who served four presidents (both parties), but the more I read about him the more I respect and even revere him. Stimson is not adequately depicted in Christopher Nolan’s otherwise outstanding film Oppenheimer. In the film, during a meeting about what Japanese cities to target with the atomic bomb, Stimson (the Secretary of War) says, glibly, that he wishes to spare Kyoto because he and his wife honeymooned there. This is not only not true, but a serious misrepresentation of and disservice to one of the great men of the 20th century. Stimson knew that Kyoto was the ancient capital of Japan, that it was one of Japan’s greatest cultural centers, and of little strategic importance. He wanted to spare it for the best of reasons. Christopher Nolan’s point — that the fate of civilizations can be that arbitrary and capricious — may have historical validity in other cases, but not in this situation. Stimson was a deeply humane man and an outstanding public servant. More than anyone else at this time, more than Oppenheimer at this time, Stimson let himself doubt the moral rectitude of using this weapon of mass destruction against a defeated enemy (for whom it was not invented). He worried that the “reputation of the United States for fair play and humanitarianism is the world’s biggest asset for peace in the coming decades,” and that the U.S. might damage its moral standing if it used the atomic device. Stimson almost alone (again, with the exception of Oppenheimer) understood the moral gravity of nuclear weaponry. He supported the use of the atomic bomb against Japan, but he refused to agree with those who believed a nuclear weapon was just a very big piece of ordinance. “This project,” he declared at a siting committee meeting in the Pentagon, “should not be considered simply in terms of military weapons, but as a new relationship of man to the universe.”

Precisely.

By the end of 1944 the world had entered an era of total war. The March 1945 fire bombings of Tokyo left 1.5 million Japanese citizens homeless and killed well more than 100,000 people. That is essentially the same death toll as Hiroshima or Nagasaki. The difference is that it took several hundred B-29s to do all that damage with conventional ordinance, but only a plutonium or uranium sphere the size of a grapefruit to vaporize Hiroshima. And just one B-29.

It is hard to think of anyone more purely admirable than Harry S. Truman. He may not have been the most gifted or intelligent or charismatic American president, but he was the greatest common American to sit in that chair. He rose to the challenge. And he was never undone by hubris. After he left office in 1953, Truman and his wife Bess returned to Independence, Missouri, where they lived in the old two-story white house at 219 Delaware Street.