The GDP of the Super Bowl is larger than some states’ budgets and the event has one great advantage as national social glue.

Well, here comes the 58th annual Super Bowl, to be played in the spectacular Allegiant Stadium in Las Vegas on Sunday, February 11. Allegiant Stadium opened on July 31, 2020, at a cost (then) of just $1.9 billion. The stadium can comfortably seat 65,000 and can strain to hold almost 72,000 people. All this at a per-person cost of $6,500. The average American would have to work approximately six weeks to purchase that one ticket — and then there are such additional incidentals as transportation, parking, food, drink, jerseys, and souvenirs. And yet, there will be no empty seats in the stadium. More than 100 million people will be watching from home. I’ll be one of them.

The Super Bowl has become an unofficial American national holiday. Though it may not be as important as Christmas, Thanksgiving, or the Fourth of July, it has one great advantage as national social glue: everyone in the country is fixed on a single monumental event, whereas we celebrate other holidays in a decentralized way at tables, churches, and picnic shelters all around the country.

I’m not sure what all of this signifies, but the GDP of the Super Bowl is larger than some states’ budgets. It feels like late capitalism in a deliriously wealthy nation. In some respects, the football game itself is the least of the circus. Last year’s pre-game festivities were so over the top that they felt like a caricature of the Super Bowl: an armed forces color guard, plus drummers from the “President’s Own United States Marine Corps Band,” an incredibly effective rendition of the national anthem by country music star Chris Stapleton; an alternative anthem, plus America the Beautiful; cuts to the entire crew of the USS Carl Vinson standing outside; giant flags; fireworks; and the first all-woman military flyover, including a live video from within one cockpit!

When the game finally started, I was so exhausted that I could hardly eat my two meat lovers’ pizzas, chips and salsa and guacamole, wings, Velveeta Rotel dip, and two quarts of pistachios. According to something called the American Pizza Community, something like 13 million pizzas are delivered to American homes on Super Bowl Sunday.

The Super Bowl has become an unapologetic festival of gaudy nationalism and patriotism, American style, with its elaborate liturgies. If you are watching from home, the pre-game shows feature heroic videos of the grit and grind of the gridiron in slow motion, a ballet of 300-pound men grappling in mud and sleet, with that perfect ominous NFL narrator intoning, “The storm broke early that November Sunday in Buffalo. …”

Americans Love Sports

Because sports are so important to the American people, we tend to process our national concerns and our culture wars through the filter of sports. I was reading a history of the glorious Oxford English Dictionary (OED) not so long ago, and I came upon a startling and fascinating sentence: “A dictionary is the history of a people from a certain point of view.” So, too, sports at all levels can be seen to represent the history of America from a certain point of view: overzealous and sometimes intrusive parenting, the capacity of money to distort the process, the quest for gender equity, the cult of celebrity; the power of television; our national love affair with violence; and above all race relations.

Here are some examples: from international relations to the long agony of race in the United States to American intoxication with violence.

The Cold War

Kurt Kemper’s College Football and American Culture in the Cold War Era is a must-read for anyone interested in the intersection of sports and the larger history of America. Somehow, our stadiums became the arenas where America’s cultural and geopolitical struggles are played out. Think of the villains in professional wrestling: in one decade with colorful names like, Igor the Terrible; in another, The Baghdad Bruiser, now Svetlana, the Savage, and then the Bronx Ayatollah. Or think of NASCAR’s decision in 2020 to ban the Confederate flag at all of its events. In 2019 Nyla Rose became the first transgender pro-wrestler in America, effectively “normalizing” the transgender movement for what would appear to be a tough audience. Over a dozen transgender or non-binary individuals now play competitive professional hockey in America.

Perhaps the most significant Cold War moment in sports came on February 22, 1980, when the U.S. hockey team defeated the Soviet team 4-3 in the Lake Placid Winter Olympics. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979 had inflamed U.S.-Soviet tensions, causing President Jimmy Carter to force a U.S. boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow. The heavily favored USSR had won the gold medal in five of the previous six Winter Olympics. Back then, in that more innocent and idealistic era, the USA still fielded amateur athletes in the Olympics. In the final seconds, Al Michaels, calling the game for ABC, shouted, “Do you believe in miracles? YES!” At the time of the millennium, Sports Illustrated declared the Miracle on Ice the top sports moment of the 20th century. Although it was “just a game,” the people of America regarded the improbable U.S. victory as a triumph of freedom and human rights over tyranny and empire.

Race

You could learn a great deal about the “long 1960s” by studying the life and career of the boxer Muhammed Ali. He was Black. He was brash at a time when white America had a hard time accepting an assertive African American. He refused to go halfway around the world to fight the war: “No Viet Cong ever called me n… .” He became a Black Muslim. He forbade white people to call him by his “colonial” birth name. After being sidelined by the American establishment at the height of his enormous talent, he fought his way back to become the Heavyweight Champion of the World. Ali became the most famous American in the world, perhaps the most famous person in the world.

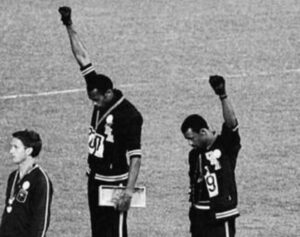

I remember the moment in 1968 at the Mexico City Olympics when two American sprinters, Tommie Smith (the gold medal) and John Carlos (bronze), faced the American flag and raised their clenched fists on the medal stand during the playing of the American national anthem. They wore human rights badges on their jackets and removed their shoes before stepping up on the platform. The president of the International Olympic Committee, Avery Brundage, forced the reluctant U.S. Olympic Committee to banish Smith and Carlos from the Mexico City games, though fortunately, they were not stripped of their medals.

When I heard about the death of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, I immediately turned on my television to learn what I could about the incident and to listen to the commentary of America’s punditry. I watched CNN, MSNBC, and FOX for a while, but then it occurred to me that it might be interesting to see what ESPN had to say about the incident if anything. When I tuned in to ESPN, I immediately realized that the commentary there was better than anything I had heard on the major news cable networks. With deep emotion and agonizing detail, African American athletes explained to program hosts what it is like to walk or “drive while Black” in America. One prominent Black athlete said no white parent whose teenage son is about to drive to the movies has to have “the talk” (for the umpteenth time): “If you are stopped, keep your hands on the wheel, make no sudden movements, above all do not mouth off to the cop. …”

Remember when Vice President Mike Pence went to the Indiana Colts-San Francisco 49ers football game in October 2017 primarily to have the opportunity to walk out in disgust on national television? When 12 players for the 49ers knelt during the singing of the national anthem, Pence headed for the exit. The latest NFL controversy began in 2026 when 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick sat during the anthem to protest racial injustice and police brutality against African Americans. The vice president said, “I left today’s Colts game because President Trump and I will not dignify any event that disrespects our soldiers, our flag, or our national anthem. At a time when so many Americans are inspiring our nation with their courage, resolve, and resilience, now, more than ever, we should rally around our flag and everything that unites us.”

Go to any sports bar after a prominent athlete speaks out about racial injustice, police profiling, or a police shooting of an unarmed Black man, and you will hear, again and again, “Why can’t these overpaid athletes just shut up and dribble.” “Just play the game and don’t meddle with politics.”

And yet, even the severe white bigots I know routinely praise their favorite Black athletes, buy their jerseys, cheer openly for them during games, select them for their fantasy teams, and cherish the opportunity to take a selfie with them. It’s a strange phenomenon. They seem to grant at least the most prominent Black athletes an exemption. Loving LeBron or Magic or Michael doesn’t mean they hold generous views of African Americans en masse, and their intense admiration for individual Black athletes doesn’t seem to have moved the needle much on their otherwise grim views. Still, the prominence of great Black athletes has surely made a difference in the civil rights movement in America.

Violence

Violence is a central dynamic of American history, from Concord Bridge (1774) and John Brown’s Raid (1859) to the Uvalde, Texas, school shooting on May 24, 2022. Pro football is a profoundly violent game. The average career in the NFL lasts 3.3 years. Naturally enough, the players we know best are generally the ones with prolonged careers, and they have even suffered what might be “career-ending” injuries. A recent Boston University study found that more than 90% of the 378 former NFL players they studied suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). This epidemic of brain injuries is the subject of the depressing but important 2015 film Concussion, starring Will Smith and Alec Baldwin. Even if Boston University’s numbers can be challenged, the percentage of former NFL players who are permanently impaired is alarming. The power of money is so great that America’s pro football players often trade a brief period of celebrity and wealth for foreshortened lives and palpable cognitive impairment. When the CTE controversy was at its height, veteran sportscaster Bob Costas wondered aloud whether NFL football could (or should) survive.

But this is America; of course it will.

We all watched in horror on January 2, 2023, when Buffalo Bills safety Damar Hamlin collapsed on the field. It was cardiac arrest on Monday Night Football. The crowd of more than 70,000 at Paycor Stadium in Cincinnati went silent as the 25-year-old man fought for life near the 50-yard line. Everyone in the stadium, everyone watching at home, reckoned that this was it — this was the moment when an NFL player would die on live TV. Thanks to excellent on-field medical attention and the resilience of youth, Hamlin survived.

The protective gear is getting better every year, and the NFL has worked hard to penalize the kinds of hits that lead to severe injuries, but we all know that it is only a matter of time.

Meanwhile, professional basketball, which long ago became a contact sport rather than a game of finesse, has reached the point where there is a foul in the paint on virtually every shot. Referees are now reduced to penalizing the worst offender in a scrum that seems more worthy of rugby than basketball.

The Super Bowl

The Super Bowl, where the score and even the participating teams are soon forgotten, but nobody forgets Janet Jackson’s “costume malfunction” or Rihanna exposing her backside repeatedly in a highly provocative way. The Super Bowl, where America’s elite corporations’ premier commercial ads cost more money than it cost to shoot Dr. Strangelove (1964) or Thelma and Louise (1991). To Twerk or Not to Twerk.

I’ve got my blender ready, and I’ve been buying two new avocados every time I go to the store. My Velveeta is still good, though it has been in a food cupboard since the Fourth of July.

Listen to our two recent podcast episodes on Sports and America:

#1584 The Red Barber Program

#1583 College Football as Cultural Lens