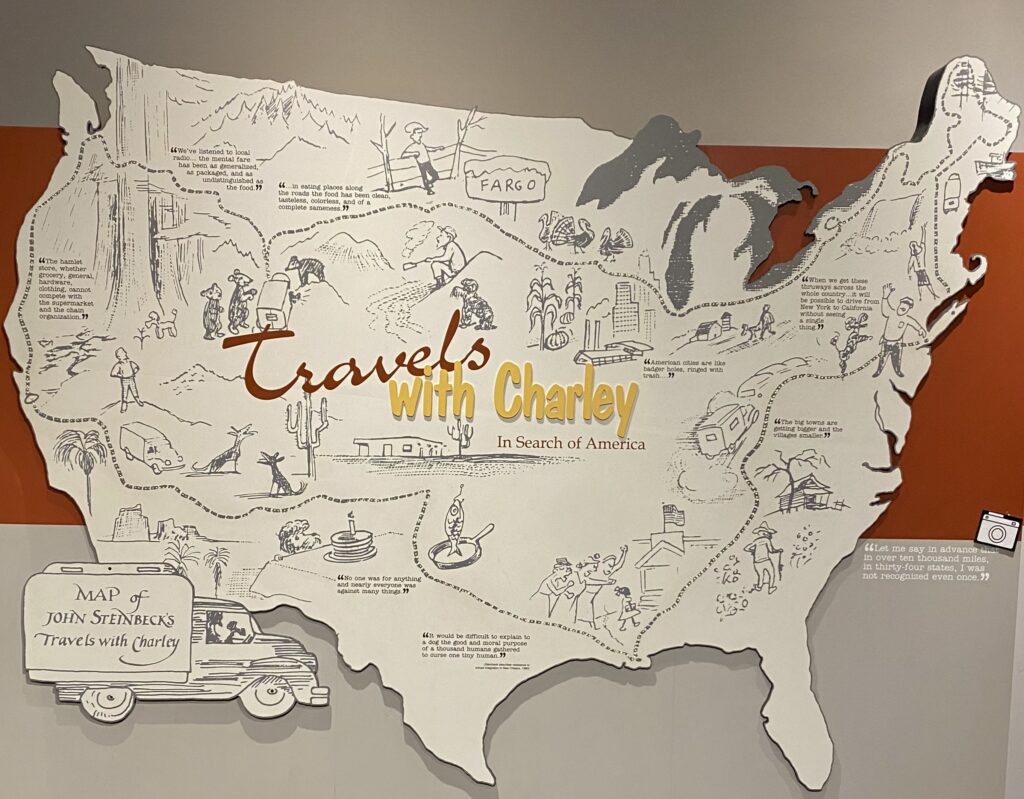

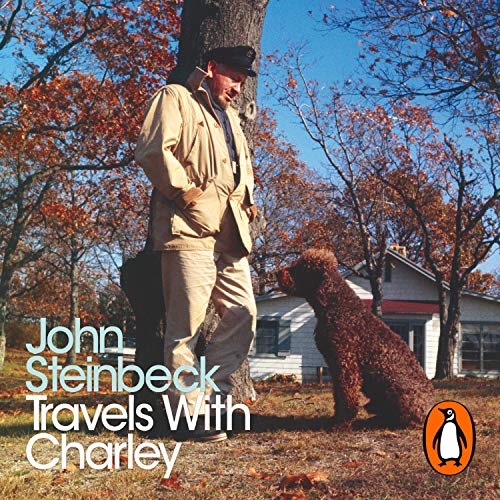

This spring, Clay departed Sag Harbor, New York, on an expedition to follow John Steinbeck’s 1960 cross-country trek immortalized in Travels with Charley. Recently, after completing the first phase of the trip, Clay reflects on what he’s learned about Steinbeck and how he now sees the story behind the classic travelogue.

I’ve been repeatedly reading John Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley: In Search of America and books about Steinbeck’s 1960 journey. I’ve also been reading Steinbeck’s letters, especially those about Travels with Charley. I’m slowly reading through Steinbeck’s 30 books, and last, but not least, I have been retracing his great journey in a 23-foot Airstream. Phase One, Sag Harbor to Bismarck, has ended. I depart for Phase Two on July 5th.

So there’s a lot of Steinbeck percolating through my heart and head these days. It turns out there are things you cannot know about Travels with Charley without getting out there and experiencing it firsthand: pace, rhythm, the nature of the roads, easy drives, hard drives, the varieties of road fatigue, the massive size of the Great Lakes, and the unfolding of the American landscape as you venture slowly west. Dozens of passages in Travels with Charley clicked into place for me as I traveled the landscapes that inspired his prose.

Here are my preliminary conclusions. Some of them may seem critical but I don’t mean them to be. I’m merely trying to understand a journey that has come to play an outsized role in my own life as a traveler. We all need to accept the essential truth: the 1960 journey is not the same as the book John Steinbeck wrote about that journey. The 1962 book is not meant to be a literal and inflexible account of everything that happened out there. There are three John Steinbecks at play here. One John Steinbeck was a 58-year-old novelist who journeyed around the United States’ perimeter. There is a second John Steinbeck, the persona who appears in Travels with Charley and tells the story of his travels. There is a third, John Steinbeck, the author who wrote the book. The three Steinbecks have much in common, but they are not identical. Travels with Charley is a work of literary nonfiction with the kind of embellishments we all bring to bear on the stories we tell of our adventures. Some critics call it autofiction. Travels with Charley is, in some respects, a novel written about a journey. It’s no more true- or false – than Kerouac’s On the Road, William Least Heat Moon’s Blue Highways, or Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, all of which are inevitably somewhat fictionalized accounts of journeys that happened in real-time.

While critics like Bill Steigerwald want to interrogate Steinbeck’s strict veracity, I’m more interested in Steinbeck’s creative strategies, first as a traveler and later as the narrator of those travels. In the twilight of his career, after many creative disappointments, Steinbeck wrote a lovely book about his travels searching for America with Charley, the poodle. For many, it is his most likable book. It is the most relaxed of the books he wrote, the most personal, with the least strain after literary greatness. I’m very interested in the differences between his journey and the narrative he constructed from that experience, but the differences don’t disgust or disillusion me. They tell us a good deal about John Steinbeck’s state of mind in the autumn of 1960, his state of health, his creative life, and his outlook on America as a man, a citizen, and a creative artist.

My preliminary conclusions.

First:

His heart wasn’t really in it. He says that he took the trip for several reasons: because he had lost touch with America, because New York City is not America, because he did not want to surrender to what Shakespeare called the “second childhood and mere oblivion” of old age; because he no longer understood what he called “this monster country;” because he wanted to prove to himself (and others, including his third wife Elaine) that he still had the right stuff.

So, Steinbeck commissioned an Indiana company to fashion a newfangled truck camper for him, and he decided to drive the perimeter of the United States alone. He engaged in extensive planning and provisioning. He defended his bold plans when those closest to him tried to talk him into something less strenuous, risky, and exhausting. He spent a lot of money to get precisely the traveling rig he envisioned. For weeks or months, he poured over maps and atlases.

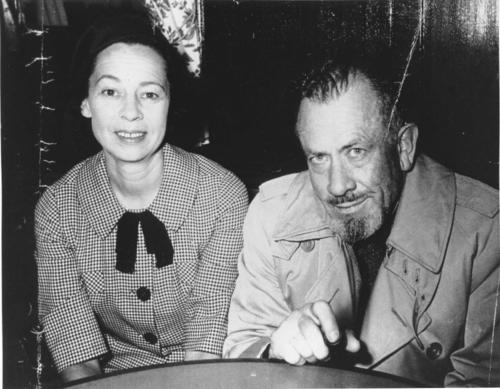

But his heart wasn’t really in it. He confesses that as the departure date neared, he half-hoped he’d find a good reason to cancel his plans. “I didn’t want to go. Something had to happen to forbid my going, but it didn’t.” When he was finally underway on September 23, 1960, he acknowledged that he mostly felt “desolation.” He admits throughout the journey that he was lonely and missed his wife, Elaine. And though he did not quite admit it, it is clear that he missed the comforts of his wealth and celebrity — drinks with his literary and artistic friends, fine dining, luxury hotels, and access to all the fruits of life for a wealthy and privileged American author.

Steinbeck started strong in New England. He devoted 68 of the 214 pages (32%) of Travels with Charley to the New England portion of the journey, where he had some specific travel goals and had meaningful encounters with farmers, a submarine operator, a fire-and-brimstone preacher, and a family of French Canadian potato harvesters. In other words, a third of the narrative only gets him to Buffalo, New York (or Erie, Pennsylvania), and the remaining two-thirds has to take him all the rest of the way around the perimeter of the United States, at least four-fifths of the total mileage and most of the nation’s geography. As soon as the initial honeymoon period of the journey wore off somewhere on the shores of the Great Lakes, he pursued the rest of it with dogged determination not to quit but without the capacity to thrive.

Second:

Steinbeck ran out of mojo long before he ran out of miles. As early as Monterey, when he had to turn the rig around and head back into the heart of America, Steinbeck confessed that he had run out of steam. “My impressionable gelatin plate was getting muddled,” he wrote. “I determined to inspect two more sections and then call it a day — Texas and a sampling of the Deep South.” That’s a slender agenda for a 3,000-mile journey back to New York. And did he really explore Texas? While crossing New Mexico, he realized, “I was driving myself, pounding out the miles because I was no longer hearing or seeing. I had passed my limit of taking in.” Texas is a mere blur. Most of the Texas chapter is about the “orgy” of conspicuous consumption he and Elaine enjoyed over Thanksgiving at a wealthy ranch in the Texas panhandle. There is nothing in Travels with Charley about the colossal size of Texas, the endlessness of trying to drive across it, its long border with Mexico, its great river system, or its many distinct bioregions. He did not explore Houston, Galveston, Dallas, Fort Worth, El Paso, or the hill country that gave America Steinbeck’s future friend Lyndon B. Johnson. Texas was just a vast amount of landscape that stood between Steinbeck and his homecoming. After New Orleans, he descended into a self-described road fugue state and just hurtled home robotically to New York, stopping only to get gas and a bit of food and to sleep for a couple of hours by the side of the road.

Travels with Charley is easily the most personal of his 30 books. And the most confessional.

Third:

Travels with Charley is easily the most personal of his 30 books. And the most confessional. Steinbeck was an exceptionally private man, and though he reveals his social and political convictions from time to time in his books, especially The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden, he seldom calls attention to himself as the author of his works. He always insisted that the book is the thing the public has a relationship with, not the author, who is just a grumpy, obsessed person (often an SOB) alone in a room with blank paper or a ledger book open before him. Nothing to be gained from knowing what kind of pencil he preferred or his daily writing habits. He writes, “I have found many Readers more interested in what I wear than in what I do. In regarding my Work, some readers profess greater Feeling for what it makes [in sales and profits] than for what it says.” But in Travels with Charley, Steinbeck was in a confessional mood for the first time. He describes his physical appearance and his physiognomy, including his reason for having a beard. He acknowledges that he had experienced several serious health episodes in the previous year. He confesses that he frequently gets lost on the journey, especially in cities. He confesses that he has lost touch with the American people. Above all, Steinbeck confesses that “I hadn’t been thinking very well of myself for some years.” This is a significant sentence.

Fourth:

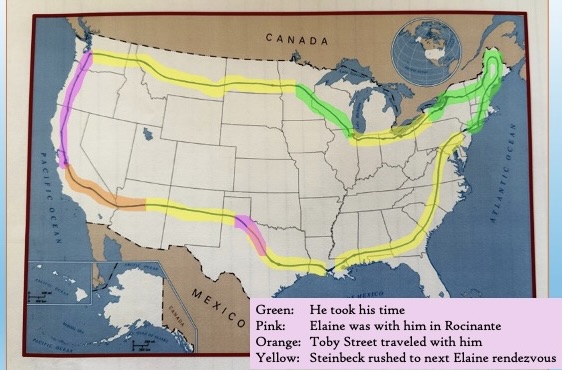

Retracing his journey (at any pace) immediately confirms how much of the time he was rushing from one Elaine encounter to the next. He rushed from Buffalo to Chicago to catch up with her. He lingered just a bit in the Midwest, from Chicago all the way to Sauk Centre, Minnesota, or even Detroit Lakes, but then he barreled across the Great Plains, the Rocky Mountain West, and the Columbia Plateau — to another encounter with Elaine in Seattle. After Thanksgiving in the Texas panhandle, once Elaine flew back to New York City from Austin, Steinbeck traveled as quickly as possible to New Orleans, briefly observed the racist women (the “cheerleaders”) who were protesting the integration of Louisiana’s schools, and then drove hell bent for leather back to New York. He admits the last of these forced marches. “My own journey started long before I left,” he writes, “and was over before I returned. I know exactly where and when it was over. Near Abingdon, in the dog-leg of Virginia, at four o’clock of a windy afternoon, without warning or good-by or kiss my foot, my journey went away and left me stranded far from home.” He confesses now that “I bulldozed blindly through West Virginia, plunged into Pennsylvania and grooved Rocinante to the great wide turnpike. There was no night, no day, no distance. I must have stopped to fill my gas tank, to walk and feed Charley, to eat, to telephone, but I don’t remember any of it.”

If you take out an atlas of the United States and do the math while tracing Steinbeck’s itinerary, you immediately realize that he raced across the bottom of the Great Lakes to Chicago. He raced from the North Dakota border to Seattle. He raced from Austin to New Orleans. And then he raced home. That leaves New England, a bit of the Midwest, the Pacific Coast Highway (with Elaine at his side), and arguably the road from Salinas, California, to Flagstaff, Arizona, as sections of the journey in which he took his time.

Fifth:

Like the great French traveler Alexis de Tocqueville before him, Steinbeck recognized that the American people are restless. In his classic study Democracy in America (1835), Tocqueville wrote: “An American will build a house in which to pass his old age and sell it before the roof is on; he will plant a garden and rent it just as the trees are coming into bearing; he will clear a field and leave others to reap the harvest.” Steinbeck makes the same point: “Could it be that Americans are a restless people, a mobile people, never satisfied with where they are as a matter of [natural] selection? The pioneers, the immigrants who peopled the continent, were the restless ones in Europe.”

Steinbeck was fascinated, possibly even obsessed, by the mobile homes and mobile home parks he first saw in his travels. He was so curious that he accepted dinner invitations from several couples who lived in mobile homes. They both told him their stories and extolled the economic benefits of mobile home living. He was impressed by the efficient floorplans of such mobile homes, their storage space, and the panoply of modern appliances. And you could just pick up and move!

Thanks to my own trip, I now understand why Steinbeck was obsessed with mobile homes. They are everywhere in New England, particularly Maine, and not so much concentrated in trailer parks as scattered individually all up and down Maine’s blue highways. The phenomenon continues 60 years later to catch the attention of all visitors.

The mistake Steinbeck made in 1960 was to overstate mobile homes’ mobility and fail to recognize how important the recreational vehicle (RV) would become as a better symbol of American mobility. Theoretically, anyone who owned one could pick up stakes quickly and have the mobile home hauled to another part of the country, but this rarely happens. Once they are settled on their foundations and the deck and other enhancements added, they seldom ever move again.

Today, RVs exhibit mobility, and some of them are larger, grander, and more luxurious than the best mobile homes of 1960. However, in Steinbeck’s time, there were few RVs and very few RV parks in the United States. The RVs of the time were modest and basic by today’s standards. Many RVs are more spacious and luxurious today than most people’s homes. It is not at all uncommon to see a dozen or more RVs the size of luxury buses, rock star buses in a single RV park, with several bathrooms, slide-outs, full bedrooms, a “home” theater, and four or five television monitors, one of which deploys outside from a compartment on the side of the rig.

Because there were so few RV parks in his time, Steinbeck frequently … well, squatted. He simply turned up a promising side road, found a level spot, and bedded down for the night. On several occasions, he was confronted by a concerned or angry property owner or his agent. On such occasions, Steinbeck was gratified to have Charley with him, for though Charley was, Steinbeck assures us, a pacifist and a coward, he could roar like a lion when a stranger approached Rocinante, and his bark was bigger than his bite — by magnitudes. Once a landowner confronted Steinbeck, the usual pattern was to apologize, offer to move, and then invite the stranger into the camper for a compensatory cup of coffee, which morphed on most occasions to coffee graced by a dollop of whiskey. In the end, Steinbeck was invited to go ahead and spend the night, and, on one occasion, the next morning, he and his antagonist went fishing together.

I wouldn’t be comfortable squatting on anyone’s private property these days. It’s a different time. And when push comes to shove, I can’t say I’ve won the Pulitzer Prize for Literature! We, the RV warriors of America, are fortunate to have lots of options today — RV parks of all sorts; Harvest Host, in which you get to spend a night on someone’s winery or ranch or dairy farm; and, of course, truck stops and Walmart parking lots.

Sixth:

“I must confess to a laxness in the matter of National Parks. I haven’t visited many of them.”

John Steinbeck

Steinbeck was surprisingly uninterested in museums, historic sites, scenic wonders, and the national parks. He drove Maine but did not slow down to explore Acadia National Park, established in 1919 during the Woodrow Wilson administration. Acadia is Maine’s only full-on national park. It finds no mention in Travels with Charley. When he stopped at Niagara Falls, which Thomas Jefferson insisted was worth a trip across the Atlantic to see, Steinbeck wrote only this. “Niagara Falls is very nice. … I’m very glad I saw it because from now on, if I am asked whether I have seen Niagara Falls, I can say yes, and be telling the truth for once.” This is different from a rousing appreciation of one of the wonders of North America.

Steinbeck wrote, “I must confess to a laxness in the matter of National Parks. I haven’t visited many of them.” He explained that he was not interested in “the deepest canyon, the highest cliff, the most stupendous works of man and nature.”

On his journey through Montana, Steinbeck dropped down briefly to Yellowstone, the first and, in the minds of many, the greatest of America’s national parks. Steinbeck characterized it as a “wonderland of nature gone nuts.” He reiterated his casual indifference to scenic wonders. He declared that Yellowstone National Park was “no more representative of America than is Disneyland,” and he admitted that he only diverted from his beeline to Seattle out of “fear of my neighbors. I could hear them say, ‘You mean you were that near to Yellowstone and didn’t go. You must be crazy.” He concluded, “I would rather see a good Brady photograph than Mount Rushmore.” Ok, then. Point made.

Earlier in his transit of Montana, Steinbeck made a side trip to visit the Little Bighorn Battlefield. He gave it one short paragraph. “We made a side trip to pay our respects to General Custer and Sitting Bull. … I removed my hat in memory of brave men, and Charley saluted in his own manner but I thought with great respect.” In other words, Charley lifted his leg and peed on the battlefield. And then they drove on.

I had only really registered Steinbeck’s indifference to these places once I began to retrace his journey. As I neared my home state of North Dakota, I diverted about 50 miles from Frazee and Detroit Lakes, through which he passed, to see again the source of the Mississippi River at Lake Itasca in Itasca State Park. The source of one of the world’s greatest rivers gets no mention in Travels with Charley. Itasca State Park, established on April 20, 1891, is not only Minnesota’s oldest state park but the second oldest state park in the United States. It held no allure to Steinbeck, who pressed on from Detroit Lakes to Fargo because “Fargo to me is brother to the fabulous places of the earth, kin to those magically remote spots mentioned by Herodotus and Marco Polo and Mandeville.” Whoa. Herodotus and Marco Polo? After this buildup, Fargo could only disappoint — and it did. What he encountered was not the Silk Road or the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, or even the hitching posts and Wells Fargo freight wagons of the Old West, but a town “as traffic-troubled, as neon-plastered, as cluttered and milling with activity as any other up-and-coming town of 46,000 souls.” After seeing nothing impressive or special about Fargo, Steinbeck traveled a few dozen miles on old U.S. Highway 10 and stopped at a roadside turnoff “to lick my mythological wounds.”

Seventh:

Although Steinbeck made a big deal about the need to travel incognito across America, lest his fame distort the conversations he sought with average Americans, I believe he revealed his identity several times. When he arrived many hours too early at the swank Ambassador East Hotel in Chicago and was told that he’d half to wait until check-in time, he managed to persuade the hotel staff to let him spend the interim resting in a room recently vacated by a traveling salesman, but not yet serviced by the housekeeping staff. Steinbeck had been driving much of the night. He was tired and grungy. Nobody likes to arrive at a hotel and be told your room is not ready. In his book, Steinbeck tells an amusing story — he informed the hotel clerks that until his room was ready, maybe he’d lounge like a vagrant in the lobby, splay out, and doze off in one of its plush chairs, surrounded by his “luggage,” which he says consisted of a cardboard box he found in the garbage can and tied with fishing line. At that point, the staff scrounged up a temporary room for him. It is hard to believe that Steinbeck did not play his celebrity card on this occasion. If ever there was an instance on the journey when it would be advantageous to reveal his true identity, this was it. At the beginning of the episode, he wrote, “I think I am well and favorably known at the Ambassador East.” That sentence probably governs the entire episode. Which is more likely that Steinbeck maintained his anonymity and played his vagrancy card to get a temporary room at the Ambassador East or that he told the management, “Look, I’m John Steinbeck, touring America for a book I’m writing, and (sotto voce) I’m traveling incognito because it’s important that I’m not recognized. Can you help me out here?”

When Steinbeck and Elaine arrived in San Francisco in November and checked into the luxurious St. Francis Hotel, he decidedly did not travel incognito. He permitted himself to be interviewed by San Francisco journalists, including Herbert Caen, one of the most prominent newspaper columnists on the West Coast. How did they know he was there? When he returned to Monterey, another interview, and he hung out at some of his old haunts with some of his old cronies from the Cannery Row days. When Steinbeck caught up with Elaine a few weeks later in Amarillo, they celebrated Thanksgiving at an ostentatious ranch (just this side of a dude ranch) owned by prominent Texans in Elaine’s social circle. There is nothing incognito about that.

I’m guessing that Steinbeck was very seldom, if ever, recognized as he traveled America. It was a time when photographs of authors were neither widely circulated nor widely recognized by the public. In addition, it’s always hard to recognize someone when they appear entirely out of context. Steinbeck usually wore a sailor hat east of the Missouri River, a Stetson west of the river. It would have been quite improbable for someone to say, “Hey, aren’t you the guy who wrote the Grapes of Wrath?” But on those very few occasions when Steinbeck wanted to be recognized, he was not, I think, averse to playing the famous author card.

Eighth:

Steinbeck said a journey of this sort had to be made alone. “Two or more people disturb the ecological complex of an area. I had to go alone and I had to be self-contained.” He was indeed correct. If Elaine and John Steinbeck had traveled America as a couple, it would have been a much different journey, a much less romantic quest, and a much less interesting book. But how much of the time was he really alone? He spent a number of days in Chicago with Elaine. A couple of weeks later, Elaine flew out to Seattle to meet him for a few days, and when he resumed the journey, Elaine was at his side in the truck camper until San Francisco, Monterey, and Salinas. After Elaine flew home to New York, Steinbeck asked his old friend Toby Street to join him on the trip’s next leg. Street was with him until Flagstaff, where he announced that he had had enough. Elaine met Steinbeck in Amarillo, and she was at his side as he drove from Amarillo to Austin. Steinbeck’s detractor, investigative journalist Bill Steigerwald, estimates that Elaine was with John about 40% of the time.

Charley is not only delightful in himself but also the source of most of the delight in the book

Ninth:

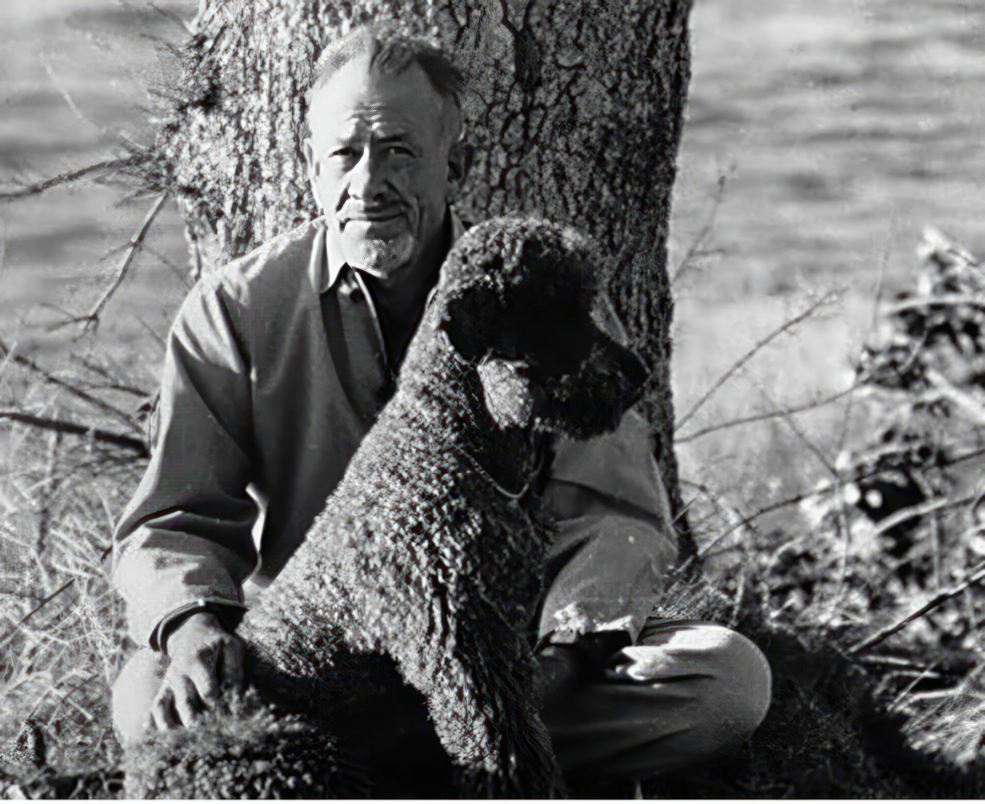

Charley, the giant poodle, is essential to Travels with Charley’s success. Remove Charley, and the book will make for a pretty thin gruel. I’ll write separately about the genius of making Charley a full-blown character in the book, with tons of personality, a great sense of timing, and a truly rich capacity for comedy. For the moment, know that Charley steals the show. He dominates the narrative with his French elan, anthropomorphic wit, and insouciant air of superiority. I’m sure the actual aging poodle added materially to Steinbeck’s pleasure on what was otherwise a lonely and often desolate journey around the United States. However, the enormous presence of Charley in the book may be the result of some literary enhancement. As he wrote Travels with Charley in the winter and spring of 1961, I believe Steinbeck realized that both his journey experience and his narrative of it were both a little thin and even a little tedious (a long essay on the ingenious mobility of mobile homes, an occasional rant about plastic wrappings for food, dishes, and toilet seats, the deepening homogeneity of American life), so he devoted more space to Charley, who thus emerges as the most interesting personality in the book. It would be fascinating to distribute two versions of Travels with Charley to two sets of readers: one in which Charley joins Steinbeck in his travels, and the other where the poodle stays back in New York with Elaine. I very much doubt that Travels with Charley would have achieved its status as a literary classic had it not been for the presence of Charley, the gap-toothed vociferator of “ftt,” a creature of timely and meaningful coughing fits, who reads Steinbeck’s mind and bends it to his will, and who decides to forgive Steinbeck “in a nauseatingly superior way” for putting him in a kennel for a few days.

Charley is not only delightful in himself but also the source of most of the delight in the book. We love dogs, especially dogs with personality and whimsy. Charley lightens the tone, reveals Steinbeck as a man of genuine sympathy, and — oddly enough — the great dog humanizes the travelogue.

Some Conclusions:

None of this is meant to find fault with John Steinbeck, certainly not to diminish the great literary achievement of Travels with Charley. Writers shape the raw material of their experiences into compelling stories. Steinbeck needed us to think that he was alone most of the time. He wasn’t. Steinbeck needed us to believe he spent most of his nights in the camper. It’s impossible to know how many nights he spent in motor courts, cabins, and hotels, but it is clear that he spent far more nights in commercial accommodations than he would have us believe. Steinbeck needed us to believe that he (a well-known American writer) could shed his fame for three months and wander unrecognized through America. It’s a very charming conceit. It is likely not entirely true.

Above all, Steinbeck did not want us to know that he spent much of his time with Elaine. That would spoil the romance of the story. In the original manuscript (now at the J.P. Morgan Library in New York City), Steinbeck provides a more accurate account of how much of the journey Elaine participated in. But most of that material was wisely excised during the editing process.

I have learned all these things by taking Steinbeck and Travels with Charley on the road. As intellectual historian Yuval Harari says, we have our experiencing self and then our narrating self, and though they overlap, they are not identical. Anyone who expects Travels with Charley to be a punctiliously faithful account of Steinbeck’s fall 1960 journey — and blames him for anything in the book that could not survive strenuous fact-checking — does not understand the nature of literary creativity.

The greatness of Travels with Charley is in Steinbeck’s relaxed writing. In this late-career book, Steinbeck lowers his guard more than he had ever done before. No matter what actually happened out there between September 23 and mid-December 1960, Steinbeck wrote a lovely, whimsical, quirky, informal, wry, and ironic book in which he confesses a great deal about what he had previously walled off as private. He does not attempt to strain for literary effect. From the book’s opening passages, he makes us want him to succeed in his lonely journey around America. We embrace the image of a distinguished American writer in khakis, a plaid wool shirt, and a ship captain’s cap reading after dark by kerosine lamp in his snug camper after he warmed up a can of chili con carne with an unusually intelligent and enterprising dog draped around his feet. I know few individuals who are not drawn to the romance of envisioning an eminent writer silhouetted with Charley behind the yellow light of his camper’s windows somewhere under the trees, sipping a snort of bourbon, traveling the whole of America in search of meaning.

It’s the relaxed Steinbeck, writing relaxed prose, that makes Travels with Charley so wonderful.

And Charley.

Over the next few months, Clay is shadowing Steinbeck’s 10,000-mile trek around the USA (and making a few detours of his own). Clay’s expedition is a central part of LTA’s big initiative to explore the country and take the pulse of America as it approaches its 250th birthday. Be sure to follow Clay’s adventures here and on Facebook — and subscribe to our newsletter.