My friend Patricia Limerick of the University of Colorado has asked me to do a series of public programs with her about Orwell’s dystopian novel, published in 1949, just six months before his death. She wondered if I might like to portray Orwell. I said no but would gladly appear on stage with her as 1984. As the book! Why not? She liked that idea. She will warm up the audience with some introductory thoughts. Patty Limerick is always fascinating to listen to, no matter the subject. Then I’ll come out as the book, maybe in a dust jacket! Limerick will ask me how I feel after 75 years. “A little dog-eared,” perhaps I’ll begin.

The question is: how prophetic was Orwell? What does he say to us in the age of “fake news” and “alternative facts”?

To get ready for this set of conversations, I reread 1984 this weekend. I hadn’t read it for 15 or 20 years.

I can only say thank goodness it is a great book because it is not much of a novel. The love plot is a little cringey now. Julia’s sexual persona was undoubtedly audacious back then, but it feels now like the sexual fantasy of an aging, unwell, and lonely writer. One of two things is true: either the protagonist Winston Smith is at heart a misogynist, or Orwell was, or both. Before they get together in their clandestine love affair, Winston, believing that she is probably a spy for the Thought Police, wants to rape her and smash her head in. That dark fantasy occurs more than once in the novel’s early pages. Nor does it seem very likely that the first words that Julia would want to express to Winston, whom she has never met — by way of a note slipped into his hand in the hallway of the Ministry of Truth — is “I love you.” He asks why. We ask why. She’s half his age, and — Winston tells us more than once — she has alluring hips.

But of course, we don’t read 1984 as a novel. We read it as a great book about totalitarianism. Sickened by Stalin’s purges and the disappearances in the Soviet Union, Orwell wrote a book about the way an autocracy based on a cult of personality stifles the human spirit. Orwell had a few glimpses of the emerging technology of television, and reckoned that at some point the monitors would be used to surveil the public and bombard it with messaging. He could not have seen where technology would take us, but my computer’s camera is on (somehow) while I write this, and it cannot be ruled out that someone is observing me. My daughter insisted that I disconnect my Alexa. The other day, a printer software company took control of my laptop to fix something preventing wireless printing. How do I know that they are not sifting through all that is stored on my computer at this moment? AI is going to magnify the capacity of the Other (whatever or whoever it is) to monitor what we do, appropriate our intellectual property, spy on our private lives, steal our wealth, and plant in our devices any compromising materials they wish.

The amazing thing is that, so far as we know, the invasion of privacy — the end of privacy — is not being engineered by an oppressive government but by corporate and consumer capitalism. The great irony is that Big Brother is not the state, not yet at any rate, but corporate giants and nonstate actors, “somebody sitting on their bed that weighs 400 pounds,” as Donald Trump put it back in 2016. Remarkably, our privacy is not being taken away. We give it away daily as we grant permissions to software apps, Facebook, and other social media.

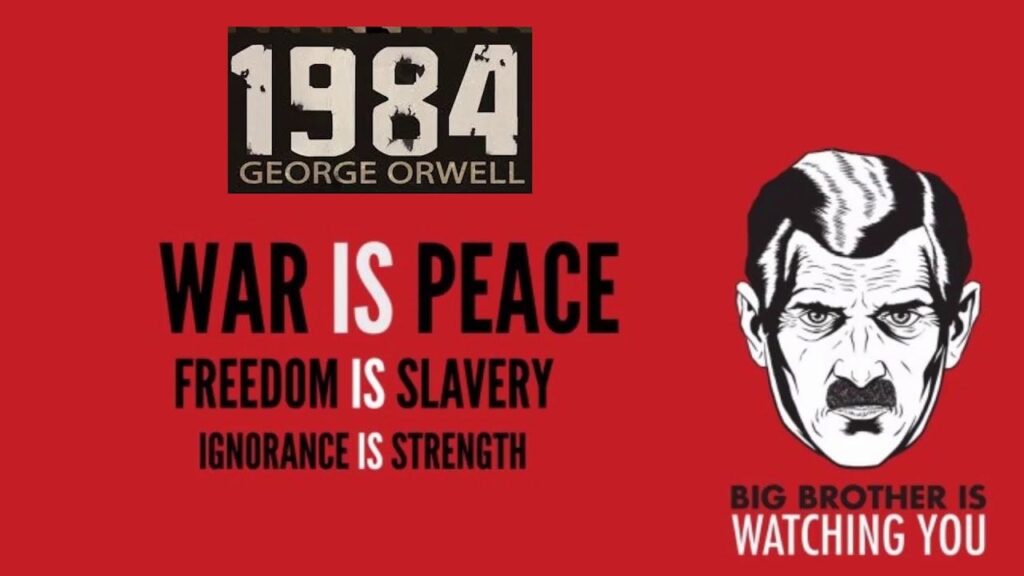

Orwell did not live long enough to enjoy the money and success that Animal Farm (1945) and 1984 brought him. He did not know that his last books had added unforgettable phrases to the English language:

Doublespeak

Newspeak

Big Brother is Watching You

Freedom is Slavery

Thought Police

War is Peace

“All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

And

“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.”

Few books undergo the magic transformation that places them squarely at the center of culture, even for those who have never read the book. Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels is such a book, as is Melville’s Moby Dick, as is Hamlet. People who have never read these books know that Gulliver is a giant among diminutive doll-like people, that Captain Ahab is in the grips of a mad obsession to kill the white whale, and that Hamlet, as Lord Olivier put it, is “a man who could not make up his mind.”

Orwell’s imaginative genius made him immortal, even in a post-literate epoch.

Everyone knows generally what we mean by Big Brother. Everyone understands that the date 1984 has particular potency, unlike 1983 or 1985. The irony of this is that the original title for the book had been The Last Man in Europe. He chose 1984 for two reasons. First, it was a long way away in 1948. Second, he merely transposed 1948 into 1984. Had he written the book in 1957, he might have titled it 1975.

The great question invoked by 1984 is what is truth? Using the clumsy technologies Orwell envisioned, the Ministry of Truth has first to alter and then actually reprint old books, magazines, and newspapers to make them consistent with the official history of Oceania. Doctoring a photograph was more difficult before digitization. Today, governments have the tools to alter what is perceived as reality, as do corporations, as do terrorists, as do political activists, as do your neighbor or your child. If you can invent a popular Taylor Swift song using AI, you can put whatever words you want into the mouths of Joe Biden, Ted Cruz, Bill Gates, Kim Kardashian, or LeBron James, including on video.

Orwell’s remarkable book is a superb introduction to the questions we should be asking ourselves today about the future of privacy, the future of surveillance, the future of intellectual property, and the future of truth.

But we need him now for the technologies that have emerged since his death in 1950 and those that are just now appearing on the digital horizon.

Today’s book should be called The End of Private Life.

P.S. As I finished writing this, I turned to my daily news feed and found this statement by Vladimir Putin just a day or two after the funeral of Alexei Navalny, his most prominent critic, who died suddenly in a Russian gulag.

“This world has no place for racism, dictatorship, double standards or lies, and people are free to speak their language and follow the beliefs and traditions of their ancestors.” — Putin.

George Orwell gave us the conceptual matrix and language to talk about moments like this.