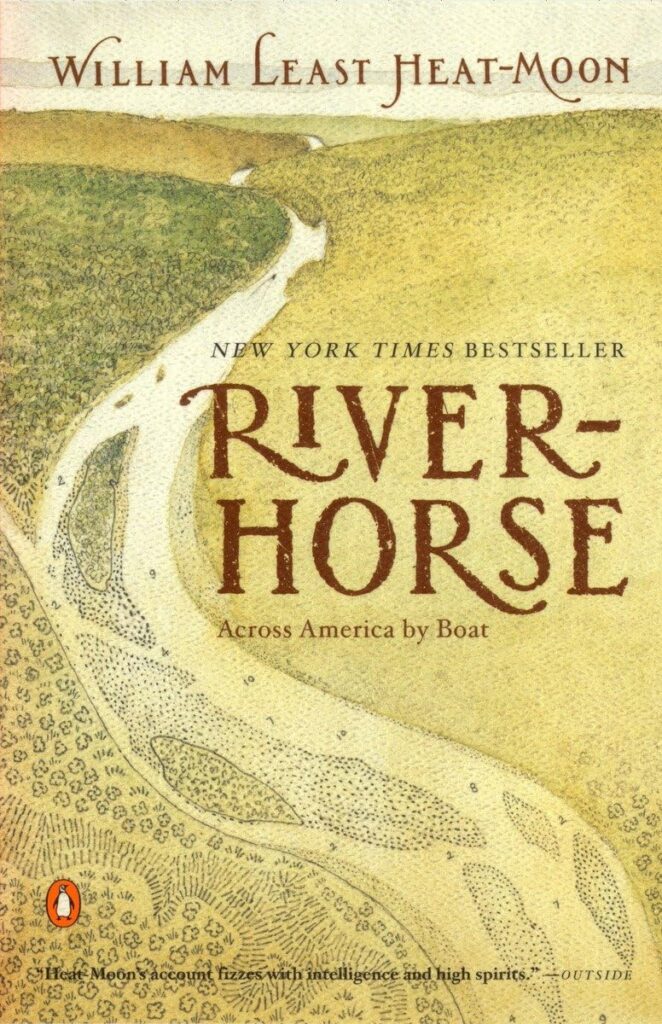

Tracing America’s Great Rivers This Summer Along the Lewis and Clark Trail, Clay Rediscovers the Power and Beauty of William Least Heat-Moon’s Forgotten Classic River-Horse: A Voyage Across America.

Self-ratout. I have, for many years, made the mistake of locking William Least Heat-Moon onto the shady asphalt trails of his 1982 blockbuster book, Blue Highways. That’s the book that made him famous, really famous. I’ve read Blue Highways six or seven times, and of course, I admire it, but some small things in it catch in my throat.

Now I’m reading Least Heat-Moon’s River-Horse: A Voyage Across America (1999). I read it once before during the bicentennial of the Lewis and Clark expedition, but I was reading it then for insights into Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, or Lewis and Clark. There weren’t many. That wasn’t the purpose of the book. I was effectively reading it the wrong way, through the wrong lens. Now that I am rereading it, several decades later, I am loving it. Least Heat-Moon notices things. He doesn’t notice the things I notice, which makes his book all the more valuable to me. His prose is strong and graceful. There is very little writing for effect.

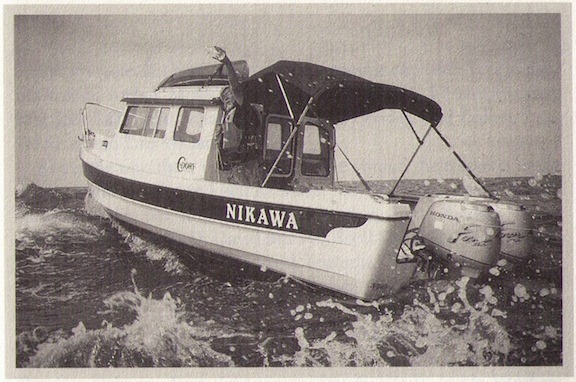

River-Horse is an account of Least Heat-Moon’s successful attempt to float American waters (rivers, the Great Lakes, the massive Missouri River reservoirs in the Dakotas and Montana) from the Atlantic to the Pacific. He and a couple of unnamed friends followed the Lewis and Clark water trail, mostly in a rugged, shallow-draft C-Dory boat named Nikawa with two outboard motors, sometimes in a canoe with a small outboard motor, and on a raft for portions of the Salmon River in Idaho.

So here I am in the early summer of 2025, reading his book while camping in the “Egyptian Triangle,” where the Ohio, Illinois, Wabash, Cumberland, Tennessee, and Missouri rivers come together to empty their prodigious waters into the Mississippi. Where so many lowland rivers meet with that much seasonably variable flow, it would be almost impossible to build a great river city like Richmond, Cincinnati, or St. Louis. You need some high ground for that. These semi-wetlands give off a swampy, backwater vibe, a stagnant-water vibe, and a primordial nature vibe. At least 60 percent of the nation’s riparian water flows through this funnel.

But here’s the rub. I have never really thought about Mississippi basin hydrology before. I’ve never studied these tributary rivers long enough to see this relatively compact landscape as a great amalgamation of waters, what Least Heat-Moon calls “one of the great fluvial junctures in the world.” I have not pored over enough hydrological maps of America. Least Heat-Moon was trying to figure out why Cairo, Illinois, never became a great river city (current population 1,558). He figured it out. Answer: no bluffs. He came to that insight either by himself or by listening carefully as a river expert explained things to him. I like that Least Heat-Moon is not afraid to credit others with some of the insights and many of the excellent anecdotes in his book. Least Heat-Moon is an exceptionally well-read man who carries a lot of information in his head. He knows how to deliver what he knows in a travel narrative that is never tedious. However, what I admire most about him is that he thinks intensely and critically about things. He’s trying to “read” the continent.

Author, William Least Heat-Moon.

The structural framework of River-Horse was to follow the Lewis and Clark water trail from the Atlantic to the Pacific, accompanied by a friend he calls Pilotis. As with Tony Horwitz’s Roger (in Blue Latitudes) or Sancho Panza (in Don Quixote) or William Clark, for that matter, Pilotis is the pragmatist who frequently tries to reason with the more romantic and mercurial Least Heat-Moon. That combination (Quixote and Panza) always enlivens a book of adventures. Least Heat-Moon makes the most of it here.

I’ve been struck again and again by some of the beautiful passages in River-Horse. Here are two of them. First, as they were about to float out of the Ohio and turn north against the currents of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, he writes:

“Tomorrow the tilt of the continent would be against us for almost three thousand miles before we might find this kind of ease again. But for now the Ohio carried us, demanding only buoyancy, and during that hour we went exactly as the river went.”

“Tilt of the continent.” That’s what gives this passage creative excellence.

And when the Nikawa first enters the mouth of the Missouri River:

“We crossed the Mississippi, and there before us opened the great Missouri charging down fiercely a flood that bulled into the other river, hit Nikawa, shimmied her [Least Heat-Moon’s perfect verb], bounced her in the confusion of waters, a violence that fulfilled my long wish for such an assertion of force.”

OK, here’s one more, it is so good:

“More than any other kind of travel, floating a river means following a natural corridor, for moving water must stay true to the cast of the land, and we liked knowing our way was so primeval and, what’s more, that in every mile we were recapitulating human routes of the previous eight thousand or more years. No other form of travel can do that.”

On this 2025 landlubber journey of mine, I’m driving along river corridors but not floating those rivers. This has seemed to me to be a delinquency. So I am canoeing the Missouri River for two separate weeks this summer and taking a whitewater raft trip on the Upper Yellowstone just as it exits the national park. When I reach Astoria, I hope to get myself aboard an excursion boat that will shimmy me over the Columbia Bar. I’ve done that once before. The “thump” of the bar takes your breath away (and maybe your life, depending on the weather).

In the meantime, however, I’m delighted to be able to share Least Heat-Moon’s journey vicariously.

I know this. I’m a little numbed out after four intense days at the mouth of the Ohio and the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi. There is a staggering amount of water gathering here. The river bridges are high, narrow, and at times frightening, particularly when giant semis are hurtling along from the other direction. When I first saw the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi a few days ago, having prepared myself for that exact moment for more than a year, I gasped. There is an appalling quantity of water at play here, and this is not even a high-water spring. I’ll breathe a little easier when I get to the Missouri above Yankton, South Dakota, where it’s magnificent, but not in an overwhelming manner.

Yesterday, I sat at the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi, daydreaming about that key heartbreaking chapter (16) of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. If there were only one American book. … Miss the Ohio, Jim says, and “no more show for freedom.”

We need more river books. Least Heat-Moon’s River-Horse pairs nicely with the late John G. Neihardt’s 1910 book The River and I, describing his float trip from Fort Benton, Montana, all the way down to Sioux City, Iowa (before the construction of the deadening and spirit-destroying dams). But Neihardt (1881-1973) was floating with the current.