On the 60th anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, are we any closer to answers? And how might things be different in our country were it not for that fateful event?

A week ago was November 22, exactly 60 years after the assassination of John F. Kennedy. I try to take time every year to re-read one of the many books I have on the assassination and watch the latest documentaries, but this year I feel especially melancholy. I think I know why. First, I ordered Paul Landis’ new book Final Witness the minute I heard about it and I read it the day it came. If it is true that Landis, who was one of JFK’s immediate Secret Service agents, tampered with key evidence at Parkland Hospital (the magic bullet), and he told nobody for six decades, not his superiors in the Service, not the Dallas police or the FBI, not the Warren Commission or the House Select Committee on Assassinations in 1976, his act of fundamental irresponsibility overturns the table of virtually all books ever published about the assassination, and demolishes much of the Warren Commission Report. That makes me angry and it makes me very sad. I don’t suppose I will ever know exactly what happened in Dallas, not in my lifetime.

I’ve also been reading extensively about the assassination this fall, for a chapter in a book I am writing on John Steinbeck’s attempt to translate the Middle English prose saga the Morte d’Arthur. One chapter is on Jacqueline Kennedy’s invention of the Camelot Myth for the Kennedy presidency, which — in an indirect but fascinating way — has a Steinbeck connection. So I have recently reread William Manchester’s work of genius, The Death of a President (1963), and Theodore White’s memoir In Search of History. Plus a lot of Steinbeck.

We now know a great deal more about John Fitzgerald Kennedy than the American people knew on November 24, 1963, and much of it is sobering. We know that JFK was an obsessive and often reckless womanizer, with ties to the Mafia. (This was largely covered up by the “men will be men” tribe of journalists in his lifetime). We know that JFK was suffering from Addison’s disease, a debilitating and life-threatening malfunction of the adrenal glands. Biographer Robert Dallek wondered out loud whether JFK would have survived a second term. We know that Kennedy was lukewarm on the Civil Rights movement and actually tried to dissuade Martin Luther King from marching on Washington in August 1963. We know that President Kennedy’s storied embrace of the American Space Program began half-heartedly when he was scanning the political horizon for something heroic and positive to attach himself to, especially after the debacle of the Bay of Pigs invasion. That’s one of the themes of Douglas Brinkley’s American Moonshot: John F. Kennedy and the Great Space Race. There is also, of course, the fact that JFK’s record of achievement was thin, first in the Senate and then in the White House.

Most Americans are aware of some of this, but it hasn’t damaged Kennedy’s gigantic place in American memory. Because he was martyred at the height of his power, because he was Hollywood handsome with a dazzling smile, a self-effacing wit, and a compelling accent, because he was a seeming idealist who wanted to carry America boldly into the future, because he had a glamorous and extraordinarily beautiful wife, plus all-American children who played in the Oval Office, and because he is associated with the cultural flowering of the 1960s … he symbolizes to almost everyone, even those who know better, a lost innocence. Although “Camelot” is an imprecise and misleading moniker for the Kennedy years, a mawkish invention of the president’s grieving widow, we all nevertheless feel that his 1,036 days in the White House do somehow represent “one brief shining moment,” after which the clouds (Vietnam, the other ’60s assassinations, Watts, the 1968 burning of American cities, etc.) began to gather over the American landscape.

In the minds of many, including serious historians, there was America before November 22, 1963, and then America after November 22. Arbitrary though that is, I find myself subscribing to something like that notion in most of my moods. What if JFK had not been cut down in his prime? How would America be different or would it be more or less the same? That would be an even greater source of disillusionment.

When he died the Beatles had not yet come to America. They were barely known on this side of the Atlantic. When he died the birth control pill was available, but usually with intimidating social restrictions. When he died, most American schools were still segregated. When he died, most Americans had never heard the word Vietnam.

When he died that Friday afternoon, we gathered before the family television, bulbous, black and white, grainy, with rabbit ears. On the day of the funeral, I saw my father cry for the first time, and nearly the last.

Who knows how things might have been different if JFK had lived? We are fortunate that we don’t know, because this way we can lock him and his elfin wife in a fantasy of eternal youth; we can insist that he would not have gotten the U.S. bogged down in Southeast Asia; we can believe that Richard Nixon would not have been able to make a comeback in 1968. Our dream of an America that did not descend into Vietnam, Watergate, the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Kent State, and Iran Contra makes us ache for an idealized Kennedy presidency.

Every year I watch two or three Kennedy assassination documentaries, and I always come away disappointed, because in all those decades nothing really has changed in the “official” narrative, not even after the release of 2,672 previously sealed documents in the summer of 2023. The annual documentaries always promise more than they deliver. New photographs are discovered! No difference. The Zapruder film has been remastered, using the latest AI programs. No difference. Graphic specialists have recreated the assassination in a precise animation. No difference. New ballistic tests have been conducted. No difference.

We are stuck with the lone gunman of the Warren Commission (now deeply disrupted by the Landis confession) on the one hand and some version of Oliver Stone’s chaotic and irresponsible CIA/Mafia/Castro/Bay of Pigs veterans conspiracy theories on the other. Three factors make me doubt the lone gunman narrative: 1) Jack Ruby; 2) the magic bullet; 3) the fact that FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover declared that the assassination was the work of just one man before Friday, November 22, had ended. How could he possibly know?

In each of these documentaries I have to watch the Zapruder film, though I can hardly stand to watch it, and see the President’s head explode into a globular pink cloud. It makes me sick to my stomach. Each time I watch the film I thank God it was shot in Kodak 8mm film and not in today’s high-definition video. And yet, if everyone in Dealey Plaza had been carrying a smartphone, we’d have several thousand angles and perspectives to hand to the forensic experts. We’d be able to triangulate the assassination.

The other reason that I am feeling the assassination with more than usual pain this year is that we as a nation and as a people have descended so far from what I’m calling the “innocence” of 1963. It’s hard to remember that the Twist was once regarded as risqué and that there were anti-Beatles clubs all over the United States, even before John said they were more popular than Jesus. The contrast between then and now is deeply saddening. Think of JFK’s Inaugural Address in 1961 (ask not … pay any price, bear any burden) and then Donald Trump’s “American Carnage” address in 2021. Think of senatorial orators like Everett Dirksen and Robert Byrd and then think of Ted Cruz and Tommy Tuberville. Think of Eric Sevareid and Walter Cronkite and then today’s principal national talking heads.

I know better but I am helpless in the face of the Kennedy Myth. Every time I hear Edward Kennedy’s eulogy for his slain brother Robert, I burst into tears. Every time I watch YouTube videos of JFK’s news conferences, I ache for that America and blush at this one. Every time I read accounts of JFK’s Nobel Prize dinner (April 29, 1962), with his famous tribute to Thomas Jefferson dining alone, I want to live in that America, with that kind of national leadership, not this one.

There is no turning back.

Somehow John F. Kennedy can be made to symbolize all that we have lost. It’s not really true, of course, and he should not have to carry that burden.

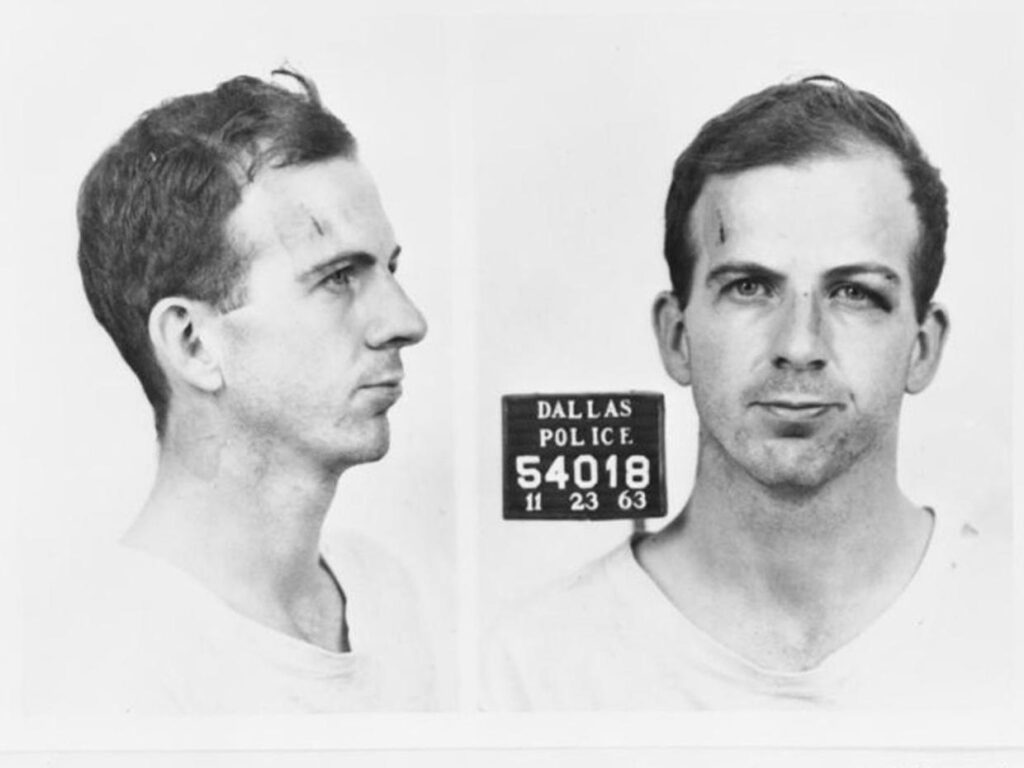

And so tonight I will sit down and choose one of a half dozen new documentaries, and watch Walter Cronkite’s voice break, and see Lee Harvey Oswald sneer in his white T-shirt, and watch Jack Ruby thrust himself forward and shoot Oswald in the gut at close range. And I will see the Zapruder film for the 250th time, not willing to watch it and not quite willing to look away.