Day Seven: In and around the town of Rifle in Western Colorado

Clay and two colleagues met near the town of Rifle in western Colorado to visit the spot where the federal government set off a nuclear device in 1969 to test the feasibility of using atomic bombs in oil “fracking.” Later in the day, they visited the gravestone of Western legend Doc Holliday and searched unsuccessfully for the local restaurant owned by Colorado Congresswoman Lauren Boebert. This is the final entry in Clay’s seven day road trip from Bismarck to Vail, Colorado.

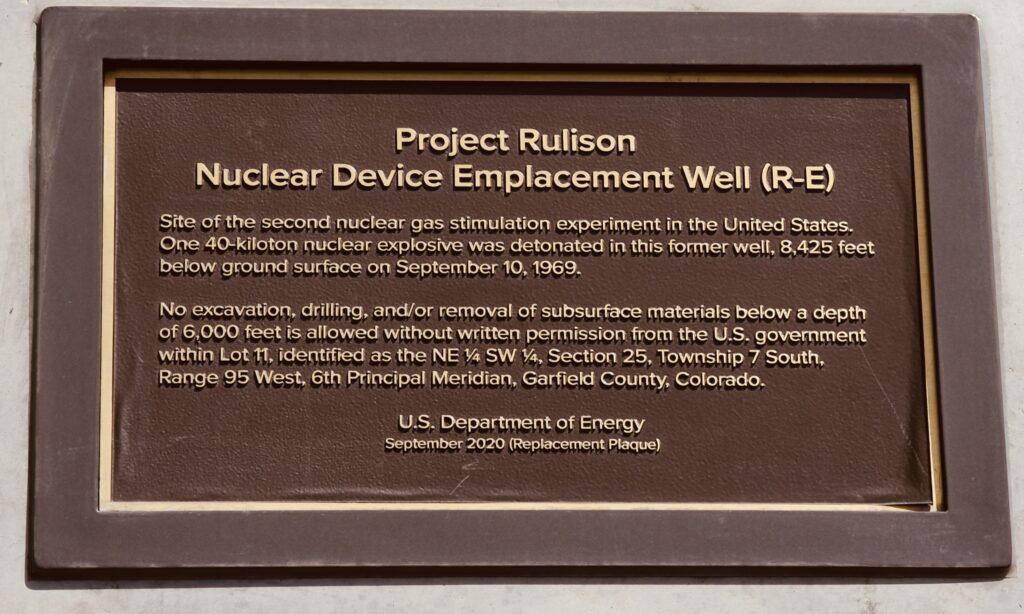

We met in Rifle because we wanted to drive up to the site of an underground atomic detonation on September 10, 1969. I’ve known about the Rulison site for many years but never visited.

The backstory to this detonation begins with the federal government’s efforts between 1957 and 1977 to find peaceful uses for nuclear bombs. The Atomic Energy Commission’s chairman Lewis Strauss (a man I revile for his efforts to destroy J. Robert Oppenheimer), boldly declared that the Plowshares Project was created to “highlight the peaceful applications of nuclear explosive devices and thereby create a climate of world opinion that is more favorable to weapons development and tests.”

Wait a minute. Read that again. Project Plowshares (1958-1975) was created to experiment with peaceful applications of nuclear fission, and the chair of the AEC says that he hopes that the project will “create a climate of world opinion that is more favorable to weapons development and tests.” Not peaceful uses of nuclear detonations for the betterment of humankind or development of infrastructure, but to build public support for weapons development.

Wild ideas were tossed about by scientists and officials at the time. What about building a new sea-to-sea canal using a pearl necklace of atomic blasts? One wit suggested it be called the Pan-Atomic Canal. What about creating an artificial harbor in Alaska? What about propelling spaceships to Mars and beyond with a series of small nuclear detonations at the end of the rockets? And the most preposterous proposal of all: detonating a nuclear device on the surface of the Moon.

Throughout the program’s life, some 35 warheads were detonated in 27 separate tests, one of them at Rifle, Colorado.

The Rulison test involved a relatively small nuclear device, 40 kilotons, just over twice the potency of the Hiroshima bomb. It was detonated at 8,400 feet below the surface. Its purpose was to fracture (frack) oil and gas-bearing shale. It fracked all right, but there was too much radiation in the gas that was released, and the quantity was disappointing. Thank goodness it didn’t work. I know people in the oil industry today who would frack all of America with nuclear devices if they had access to the device. The U.S. government did not give up yet. One final test occurred on May 17, 1973, 45 miles north of Grand Junction, Colorado. It was called the Rio Blanco test. Three 30-kiloton detonations occurred simultaneously at 5,768, 6,152, and 6,611 feet below the surface — actual plans called for using hundreds of such devices if the fracking was successful. Fortunately, the three blast cavities did not interconnect as the engineers had hoped, and the gas was — you guessed it — radioactive, NOT too toxic to be approved by the AEC, but too potent for the public, who made it clear they did not want to be running atomic gas through their water heaters and stoves.

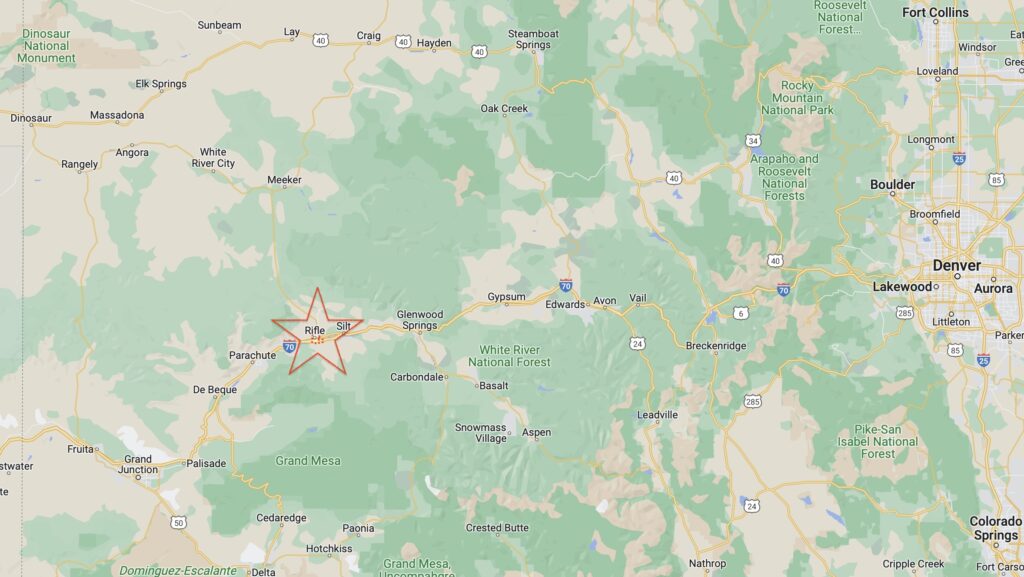

I don’t know what I expected the landscape at the Rulison site to be, but I pictured a vast and desolate plateau with distant mountains on the horizon, a pre- and post-detonation wasteland. But it wasn’t that at all! The Rulison test took place on the north side of an astonishingly beautiful mountain. There are hundreds of such mountain valleys from British Columbia through Mexico, but Colorado specializes in them. They are knee-saggingly beautiful. If you had called me in 1969 and asked me to find a place somewhere in the American West to detonate an underground nuclear device, I would never have chosen the Rulison site, even if it were one of the largest gas storage mountains in the world.

Fortunately, the underground test did not rearrange the surface landscape. There were a series of modest earthquakes in the months afterward. But no three-headed bats were born at the site. And if you did not know it was there, confirmed by signage and a plaque, you would never guess that the most destructive thing humans have ever done blew out the basement of this Edenic mountain.

A Stop at Doc Holliday’s Grave

As we drove back to Rifle for dinner, we spotted a sign in Glenwood Springs pointing to Doc Holliday’s grave. Doc Holliday’s grave! We all wanted to see that, so we turned off and found the parking lot. The graveyard where he is buried is at the end of a half-mile hike uphill. Moderately strenuous. Frank took one look at the trail and said he and Holliday had quarreled late in the gunslinger’s life and he had no interest in making the pilgrimage to his grave. So, Dennis and I chugged our way up the hill.

We knew very little about John Henry Holliday (1851-1877). He was a dentist, a gambler, a killer, a friend of Wyatt Earp. Holliday was with Earp at the infamous gunfight at the OK Corral in Tombstone, Arizona (October 26, 1881). He came west hoping that the dry climate would alleviate his tuberculosis, from which he died at the Hotel Glenwood on November 8, 1887. He was just 36 years old. We all agreed that Val Kilmer IS Doc Holliday and Doc Holliday is Val Kilmer.

Searching for Lauren Boebert’s Restaurant in Downtown Rifle

That evening we wanted to have dinner at Lauren Boebert’s restaurant in downtown Rifle, the aptly named Shooters. We found the location but discovered that Shooters had closed. The owner of the building had declined to renew the lease. It was now a Mexican restaurant. We were crestfallen, for who does not want one’s server to be packing a live .358 magnum? We wound up at a Thai and sushi place down the street. The food was excellent. We reviewed the day and planned future Listening to America expeditions. Frank hoarded the Pad Thai.

Here’s what we know about Ms. Boebert. She is 36 years old. She is a rootin’ tootin’ gun rights advocate. She has owned and managed three restaurants in Rifle, all of which have failed. She won re-election to a second Congressional term in 2022 by just 546 votes. She believes that Donald Trump won the 2020 presidential election. She is anti-abortion, anti-sex education, and against same-sex marriage. She describes herself as a born-again Christian and declares she is “tired of this separation of church and state junk.” This would suggest a weak understanding of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution and Article II, Section IV of the Colorado Bill of Rights. Her highest education achievement was a GED in 2020.

But as I walked along the main street of Rifle, studying its shops and keeping a mental tab of the town’s amenities, including on side streets, I gained a measure of respect for Ms. Boebert. It’s not about her politics. It’s the fact that after an unsettled beginning in life, without great family stability, she decided to run for the Congress of the United States. It takes work to be elected to Congress. You have to want it in a big way, have to raise money, have to listen to a lot of people you don’t care much about, have to construct a simple but compelling personal narrative, have to be able to say a few things about the issues, and you have to entrust yourself to intense public scrutiny. Some of it is going to be ugly. But young Lauren Boebert did it. She won. I’ve never been elected to Congress, or the state legislature, or to the city council or to the neighborhood recreational board. She beat a candidate from Aspen, Colorado, one of North America’s four or five most privileged places. It is a small-town girl made good story. Whether you approve or strongly disapprove of her politics and her methods, she won. That’s how democracy works. Many young people struggle to get out of such towns and fall back. She not only got out, but she is now in a position to do good things for her big chunk of Colorado (approximately half). In the end, constituent services are more important than public rhetoric.

Let’s say that I gained some respect for Lauren Boebert. Then she got into a bickering incident on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives with Georgia’s Marjorie Taylor Green.

Wedding Crashers

My friend Dennis and I happened upon a happening at the county fairgrounds. We turned in to see what had brought hundreds of cars and trucks together. It was a Hispanic wedding. We approached shyly just as the bride and groom danced the first dance out in the middle of the vast hard dirt floor — to thundering music. On each side of the enormous dance arena, scores of tables were covered with wedding tablecloths and ornaments. One giant line of food trays and those aluminum one-time-use dishes. Huge cattle troughs full of iced cans of Modelo. If we were boys out of Kerouac, we would have made creeping advances on the buffet line and helped ourselves to a wonderful feast. But we didn’t have the right stuff. We didn’t think we could pull it off. We rehearsed our wedding crasher’s narratives, whether we were friends or only former business partners with the groom’s late grandfather. We didn’t want to intrude.

We observed all that happiness for half an hour. Hardy men carried gigantic coolers the size of hay bales into the mix. It was hard to see the band through the haze, some of it caused by indoor fireworks effects, but we could hear it. Eight or 10 musicians had the sound up high and were rocking that metal prefab building like a Chautauqua tent on a breezy afternoon. At one point, a long song took place during which the groom was unceremoniously hefted onto the shoulders and extended hands of about a dozen of his “closest friends.” He flailed happily and leaped from a horizontal position to the beat of the music.

It was the largest wedding I’ve ever been near. It was as joyous a celebration as you could ever imagine. Talk about life-affirming. I could not have guessed that such a wedding would take place at Rifle, Colorado, but that’s an indictment of me, an indication of my ignorance and poverty of my imagination. It shows how fundamentally sheltered my life has been. We were filled with admiration and wonder. Walking to the parking lot, I felt like the squarest Anglo in Garfield County. It was clear that the party phase of the evening was just getting started. Children were dancing in circles all over the floor. Mothers told them to settle down and then gave up.

We headed back to the parking lot as I was soon due up I-70 a bit, in Vail, Colorado.

In June, Clay drove from his home in Bismarck, North Dakota to Vail, Colorado. A focus of Clay’s two-week road trip was exploring little-remembered sites of tragic encounters between Native Americans and an expanding, westward-moving white population of the 1860-1880s. Clay’s stops included a battle site at Whitestone Hill in North Dakota in 1863, as well as the spot in Nebraska where Crazy Horse was killed in 1877, and Colorado sites commemorating the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864. Along the way, Clay also visited the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site, the U.S. National Grasslands, and a forgotten mountainside in western Colorado, where the federal government detonated a nuclear bomb in 1969 in an experiment to explore the peaceful use of atomic weapons. And — as in all good journeys — unexpected and unrelated roadside distractions provided plenty of ways to think about America.