At the moment, I am reading Geert Mak’s In America: Travels with John Steinbeck.

I’m underlining and copying out all sorts of passages. Mak’s In America is without question the best book ever written by someone retracing John Steinbeck’s 1960 Travels with Charley journey. Mak compares with Alexis de Tocqueville, whose 1835 Democracy in America is widely regarded as the best book ever written about America by a foreigner. In America, is a mirror we can gaze into if we have the courage to do so. To see ourselves reflected in the eyes of a thoughtful and not uncritical foreign observer is a gift to us as Americans.

So here I am on page 284 of In America, and Geert Mak, a Dutch journalist, and man of letters, turns to Jefferson and the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

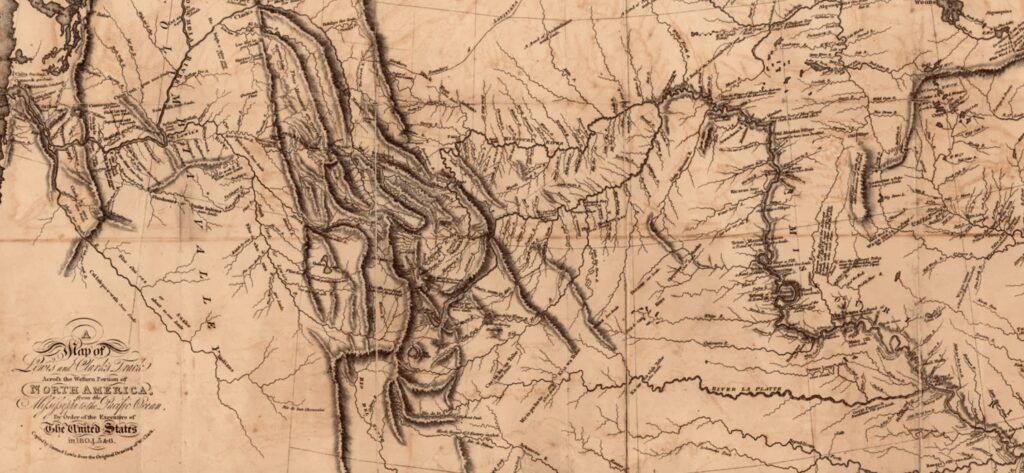

Now, this is something I know a great deal about. Mak rightly says that in 1800, the Euro-Americans did not know much about the continent’s deep interior. There were lots of blank spots, conjectural rivers, and mountain ranges. The Aaron Arrowsmith map of North America in 1800 has blanks and “terra incognita” worthy of a mid-19th century map of Africa.

Then Mak writes:

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson set up a Corps of Discovery, and in 1804, thirty soldiers and Native scouts set off from St. Louis, led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. Their task was to seek a trade route from the eastern seaboard to the west coast and, if possible, a northern passage for shipping to Asia. They were also ordered to investigate opportunities for economic exploitation of the West of the continent.

In total, they covered 8,000 miles …

Ok. It was 7,689 miles, to be exact. In May 1804, about 50, not 30, men left St. Charles, Missouri, for the journey to the Pacific Coast and back. There were no “Native scouts” unless you regard the expedition’s best hunter and trailsman, George Drouillard (part Pawnee, part French), as a Native scout.

These are small matters, perhaps even harmless errors — especially in a book about something else.

Then, however, things begin to trouble me. I suppose it can be said that Lewis and Clark were seeking a trade route and a northern passage for shipping to Asia, but this is the least positive gloss Mak could give that extraordinary mission of discovery. Jefferson wanted to know what was out there in the country, “two thousand miles in width upon which the foot of civilized man had never trodden,” as Lewis put it, as they left their winter quarters in North Dakota. Lewis and Clark were conducting an inventory of the continent, or at least of the Louisiana Purchase, consummated by Jefferson in 1803. They were amateur Enlightenment scientists, particularly Lewis, performing all the rites of latitude and longitude to locate every remarkable thing they observed on the world grid. They were ethnographers expected to bring back data (including vocabularies) about the more than 50 Native American nations they met to make commercial trading posts possible deep in the interior and help Enlightenment thinkers work out what was then called “the science of man.”

There was a high-mindedness to the Lewis and Clark Expedition that Mak fails to acknowledge.

I don’t know if Geert Mak is trying to belittle Lewis and Clark by making them primarily agents of commercial trade, like early advance men for UPS or FedEx. Or if that is how he understands the story. If any American episode deserves to be regarded as an American Epic, it is the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

At least he did not say Sacagawea was their guide.

Did Lewis and Clark come back to report that the West was “mostly desert, incapable of cultivation, unfit for white people?” I don’t see evidence for that. Lewis thought part of eastern Montana was too arid to be settled by white people (he was apparently correct), and he found the Great Plains’ treelessness eerie and bewildering. Still, I don’t think he wrote the West off as uninhabitable. He did wonder what settlers would use for building their houses and fences.

Small matters in a large and impressive book. I’ll be interviewing Mr. Mak in a couple of weeks. He will dial in from the low countries. I’ll be here on the Great Plains and don’t intend to bring any of this up. There are too many splendid insights to get stuck on this hobby horse. But if he returns to America, I plan to show him some wonders along the Lewis and Clark Trail.