A lighter report on heavier cuisine as Clay takes a gastronomic excursion through the American South.

It was out around Turkey, Texas, where I lost control of my nutritional life. One of the joys of having a trailer with a pretty large refrigerator is that all summer and fall, I could eat when and what I wished. By the end of the day, on the nation’s highways, I was usually not particularly hungry. Driving America is a largely sedentary thing. You turn the wheel. You put your right foot on the gas or the brakes unless you are under cruise control, in which you don’t do much of anything. At the gas stations (every 225 miles), you get out, slide your card, open the gas tank, and insert the nozzle. Maybe go in to pee and buy a small bag of almonds. In the evening, at an RV campground, I might heat a can of soup and have a few crackers, cheese, and a glass or two of wine. Once a week or so, I boiled some pasta. Occasionally, I grilled a couple of cheeseburgers on the nearest picnic table on my small portable grill. I seldom ate at cafés and even less often in restaurants. I have friends who are foodies (keep reading!). I like a good steak, mushroom soup, or cacio e pepe, as well as the next guy. Still, I am closer to the ancient Greek Cynic philosopher Diogenes than to gourmet diners: eat only to banish hunger, sleep only to banish fatigue.

Then, I crossed the border from New Mexico into the panhandle of Texas. The billboards of eastern New Mexico said, “Exit Here. Last Chance for Marijuana Dispensary.” And when I was officially across the border and within the republic of Texas, the billboards read, “Busted for Weed? Call 800-666-6666.” My friend Joe, a talented Amarillo attorney, confirmed that the Texas state patrol officers hover at the border to arrest and torment those fools who carry the controlled substance into their jurisdiction and that now there are a large number of defense attorneys in Amarillo, Lubbock, and Odessa (technically known as cormorants!) who specialize in representing such poor busted bastards as the Texas Rangers entrap.

As I puzzled all of this — the absurd notion in the 21st century that recreational marijuana is a greater threat to the social order than, say, a case of beer or a quart of whiskey — I saw two further billboards. One invited me to stay in the “Largest RV Campground in Texas,” and the other declared that I could have a free 72-ounce beefsteak if I could eat it in one hour.

Welcome to the Big Texan Steak Ranch. Not Big Texan Steak Bistro, Big Texan Café, or even BTS restaurant. Steak Ranch. The name sounds absurd until you venture in. The only other word that might serve would be Big Texan Steak Warehouse, which does not do justice to the romance of the Old West.

It’s a legendary beef roadhouse, painted bright yellow, on the west end of Amarillo. The roof is boisterously festooned with a series of Texas flags. There’s a giant white-faced Hereford cow effigy in the parking lot. The walls inside are decorated with hides and horns, and ranch and cowboy artwork. I may be wrong, but everything inside appears to have a patina of grilled steak effusion. I’ve been hearing about the Big Texan for years. Those who take on the challenge of trying to devour a 6 pound steak in just one hour, dine — if that is not too big a word for a vast arena of beef cuts, with some corn on the cob thrown in to create a balanced dining experience — on a stage or dais, and the crowd (on two levels) cheers and jeers. There is an entertaining comic movie starring Dan Aykroyd and John Candy, The Great Outdoors (1988), set in resort country of Wisconsin, in which Chet (John Candy) attempts to eat the “Big 96” at a similar emporium with predictable results. My expectations for a great meal were low, with little hope of a salon conversation about Foucault or Wittgenstein, but my expectation of a quintessential Texas tourism moment was high.

Joe took me there the way someone from Rapid City takes you to Mount Rushmore when you visit. As we drove into the gigantic parking lot, worthy of a small town civic center, I asked him the obvious question. “How often do you eat here when you are not shepherding a guest from somewhere other than Texas?” “Never,” he said.

Vast though the Big Texan Steak Ranch was, we were informed by a fetching and fringed girl-next-door cowgirl that it would be a 30 minute wait — the rare warehouse restaurant waiting list. So we headed into the bar, found a stray empty table, sat down, and ordered beers. Beer is what you drink at a place like this. A dirty gin martini is not the ideal lubricant for a hearty beef dinner. As we chatted about the state of America on the eve of the 2024 presidential election, we noticed a young man, somewhere in his late 20s, eating alone at a table next to the wall. He had a huge basket of deep-fried food in front of him. Suddenly, he was standing over our table. He said, “I’ve made a mistake. I ordered the big order of oysters. There are too many for me. I’d like to offer you as many as you wish.” He could not have been more polite, as if he had been reading Owen Wister’s The Virginian.

I’m a North Dakotan. I grew up in beef country. I’ve spent a considerable amount of branding and castrating time on ranches in the badlands. I knew instantly what “oyster” meant. We were offered a large basket containing about 30 breaded and deep-fat fried calves’ testicles. Where is Diogenes when you need him? This was not my first Rocky Mountain Oyster encounter. Not my first rodeo. I suppose there are people in America who actually find Rocky Mountain Oysters, also sometimes called Montana Tendergroins or Cowboy Caviar, delicious, but mostly the breaded and deep-fat-fried gonads are offered up as a test, a trial of manliness, a determination whether you are authentically of the West or just some urban pudknocker. For several semesters, I taught the humanities at the Rome campus of the University of Mary, a fine Catholic liberal arts college located south of Bismarck, North Dakota. One of the students, a Catholic Studies major, was from the ranch world near Killdeer, North Dakota, the closest we have to an actual cowboy town about a hundred miles west of the Missouri River. One afternoon in the heart of Rome, not far from the Pantheon, she told a group of her classmates, gullible Minnesotans, that she regarded Rocky Mountain Oysters as her favorite food. Without even stopping to ponder that, I blurted out, “No, you don’t. You don’t really believe Rocky Mountain Oysters are your favorite food. Compared to what? A perfect steak? Pizza? A shrimp and lobster dinner? Tiramisu?” She was offended. She affirmed in the highest state of indignation that she knew her palate (perhaps I inflate her language) better than I did, and RMOs were indeed her favorite food. I said again, “No, they aren’t,” and then we let it go. I leave it to you to decide who was telling the truth and who was posturing about the Code of the West. I saw her a year or so later with her pals at a fine restaurant on the main street of Bismarck. If Rocky Mountain Oysters had been on the menu, I would have sent over a basket for everyone’s gastronomic pleasure.

Joe and I tried to decline the offer of oysters, but the young man was very earnest and insistent, so we each took two and then spent the next 40 minutes chawing them and eventually swallowing them to prove that we were real men.

Again, welcome to Texas.

When we were seated at a table recently abandoned by a family of four big feeders (big in both senses of the term), and the cowgirl server appeared, all smiles and bedazzled denim, plus cowgirl boots, I ordered a pitifully modest 9 ounce steak, a loaded baked potato, a house salad (no French dressing, alas) and onion rings. This was a 4,000 calorie meal, and the Big Texan Ranch would not be comping me if I could ingest it all. Joe ordered roughly the same meal.

While we were there, two men accomplished the great feat. They ate the 72-ounce steak, a dinner roll with butter, a side salad, and one large breaded shrimp (all required by the challenge) in under an hour. There was much raucous celebration throughout the Steak Ranch. They drifted off to die.

I’ve been to a few big steak emporia over the years, including the Fort near Denver, but this was the most utilitarian. It’s about getting approximately 100,000 steaks per year out of the cow and onto the plate with the fewest possible distractions. The Big Texan Steak Ranch was an experience I will neither forget nor repeat. The entertainment value is better than the food, which is just fine. The state of Texas is a place of great pride and self-love (size matters), but it is often a caricature of itself at the same time.

A few days later, Joe took time off his hyper-demanding work to take me on a tour of the panhandle of Texas; I had the pleasure of spending a whole day with Joe — usually too busy to breathe. He took me through the giant JA Ranch, one of the oldest in Texas. The ranch was carved out of the endless southern plains grassland ca. 1876 (the year Custer perished on the Little Bighorn) by two legends of cattle history: John George Adair and Charles Goodnight, one of the saviors of the buffalo and the apparent inventor of the chuckwagon. Joe took me to Caprock State Park.

He also took me — the ostensible point of the sojourn — to the ranch where John and Elaine Steinbeck spent Thanksgiving 1960. (I’m trying to get myself to every important Steinbeck site in America, and I’m starting to get pretty close.) Elaine had connections there — former brother-in-law, first marriage, long story. Steinbeck wrote about the holiday with some bemusement in Travels with Charley. He called the experience an orgy of opulence and conspicuous hospitality on “a beautiful ranch, rich in water and trees and grazing land.” Joe and I talked our way down the long gravel approach drive and took a few photographs of the headquarters, seemingly unchanged since the orgy of 1960. Unlikely to be invited to stay for Thanksgiving (just a couple of weeks away), we reluctantly drove on.

Turkey, Texas.

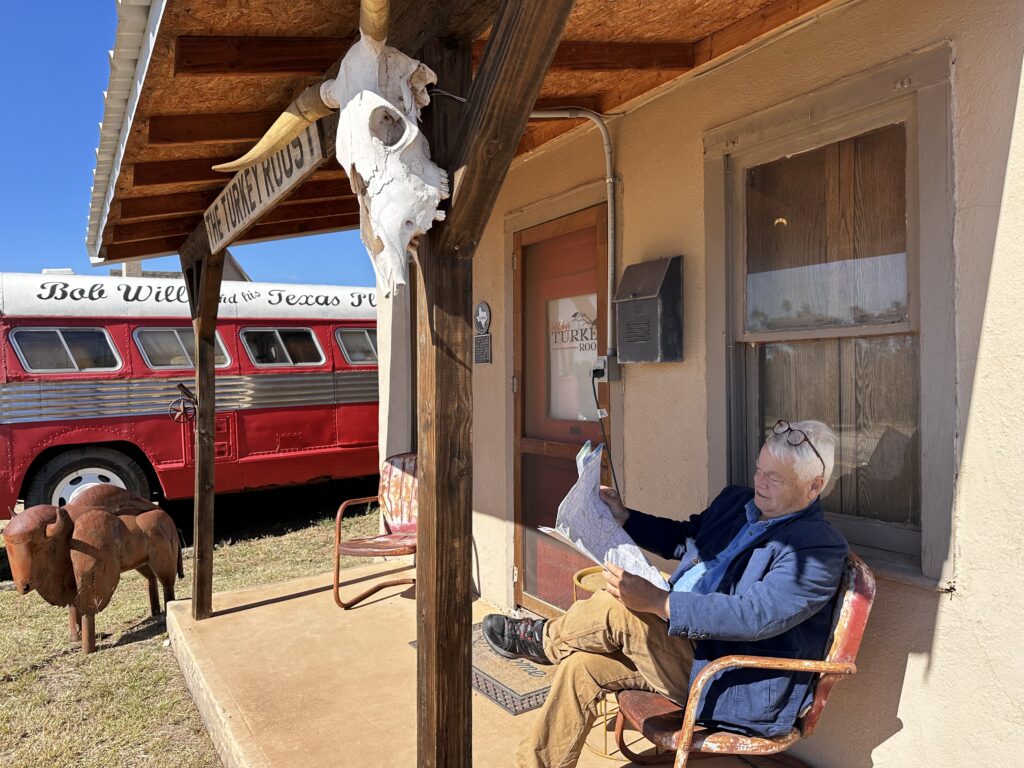

Then we stopped in Turkey, Texas, the home of the country singer Bob Wills (1905-1975). Faded Love. Bubbles in My Beer. The village of Turkey has a population of 325. It is one of the hundreds of Great Plains towns barely hanging on. I love them for their windswept plight. We soon exhausted the photo ops in Turkey, where Phillips 66 got its start in Texas, but we needed lunch, so we crossed the broad main street to Letty’s Café, a rose stucco building with a big Edward Hopper picture window and a hand-scrawled sign about the daily special.

We were the only people in the café at noontime. Our server, a quintessential small-town woman dedicated to pragmatism, sauntered over with two ribbed plastic cups of ice water and two laminated menus. I was thinking of ordering the safe and inevitable cheeseburger or perhaps a salad. But as I waited for my soda, Joe lit up with delight. “Hey, Jenkinson, they have chicken fried steak,” I confessed to having lived on this earth for many decades, much of it on the Great Plains, yet I had never eaten a chicken fried steak. I looked over at Joe’s shining eyes and said, “Generally speaking, I regard anything that is breaded as suspect, as with French sauces in the ages before refrigeration.” Joe gave me a withering look. And then he quoted Larry McMurtry, the inevitable Texas author and final word on any number of subjects. “Only a rank degenerate would drive 1,500 miles across Texas without eating a chicken fried steak.” This is from his book, In a Narrow Grave: Essays on Texas (1968).

That settled it, of course. I did not want to join the ranks of the degenerate.

In due course, or as Huck Finn would say, by and by, the server wandered over with two huge plates. “Gravy?” I asked Joe, my guide to Texas. “Of course, and only white gravy. Never accept a chicken fried steak with brown gravy.” I made a mental note.

I ate some CFS and said, yeah, ok, it’s good enough. But Joe said it was one of the better CFSs he’s ever had. It was surprisingly tender because — said Joe — they beat the living daylights out of the slender hank of beef before they bread it. By the time we left, there were two other tables at Letty’s, occupied by older couples, and, sure enough, they ordered the requisite chicken fried steaks.

We chatted with our server before we left. She had moved to Turkey (this one: not the one of Istanbul and Cappadocia) 20 years ago, and at first, she was not that pleased to live in a mere whiff of a town in the middle of nowhere, but Turkey had grown on her, and now she would not want to live anywhere else. These days, she can hardly stand to spend an afternoon in the Sodom and Gomorrah of Amarillo (202,000), 102 miles away. As we stood up to leave, I heard a loud pounding sound from back in the kitchen. I thought there was a blacksmith forge back there. But when I enquired, our host said the cook was back there tenderizing more beef for the evening rush.

East to Norlins and Great Gumbo

For a couple of years, my friend Liz Eagle and I have engaged in a sustained debate about gumbo. I live in North Dakota, where we eat borscht and knoephla soup, not gumbo. Whenever I am in the South or on the southern Great Plains, if there is gumbo on the menu, I am tempted to order it. I regard it as a moderately tasty stew and don’t long for it between bouts. I do not regard it as a delicacy. That alone is heresy in Liz’s eyes. If I make the mistake in a text of mentioning any gumbo encounter to Liz (and her husband Russ) I receive a blistering rebuke: “Whatever you think you ate, it warn’t true gumbo. The only true gumbo is found in New Orleans. How dare you mistake whatever gruel you just ate for authentic gumbo.” Etc.

Jeez. I thought you’d be pleased, Liz. Liz is the nicest person who ever lived, but she is a gumbo “soup Nazi.” For several years, she has promised me proof if only I would come to New Orleans when they could meet me there.

The word gumbo derives from a West African (Angolan) word, “ki ngombo,” which apparently means okra. Okra was part of the great Columbian Exchange and was brought to the New World in slave ships. It became a staple of several southern dishes, mostly as a soup thickener. Or as the Wikipedia article deliciously puts it: “The pods of the plant are mucilaginous, resulting in the characteristic “goo” or slime when the seed pods are cooked; the mucilage contains soluble fiber.” Yum. Can’t wait.

I only reckoned I could keep the friendship if I submitted to the New Orleans gumbo fest, so we met at a hotel near the Mississippi River late on a November afternoon. Russ and Liz had flown in from North Carolina. I had come in from Texas. Earlier that day, I announced the time of my arrival by text, and Liz replied, “Our friend Ray and his kitchen staff have been working all day to prepare your gumbo and other local cuisine for you.” Whoa. It had not occurred to me that this would be a formal ceremony, that a fuss was being made on my behalf. After I had deposited my luggage and brushed my teeth (one wants a completely clear palate), we hopped into an Uber and Ubered 38 minutes to a remote restaurant called MeMe’s Bar and Grill in Chalmette, Louisiana. In my naiveté, I had reckoned the restaurant in question would be in the heart of New Orleans, but no. This was beginning to feel like a Quest for the Holy Grail.

When we finally arrived, we were met by Ray Gumpert, the lean and talented sommelier at MeMe’s, an old friend of Russ. They go way back, and Russ has been, thanks to Ray and his friends, the recipient of some mighty great meals and wines over the decades in a range of zip codes. Ray greeted me with generosity touched with amusement that so great a kingombo ignoramus was in his midst. He said he had four different wines to share with us tonight, including an outstanding preliminary sparkling wine.

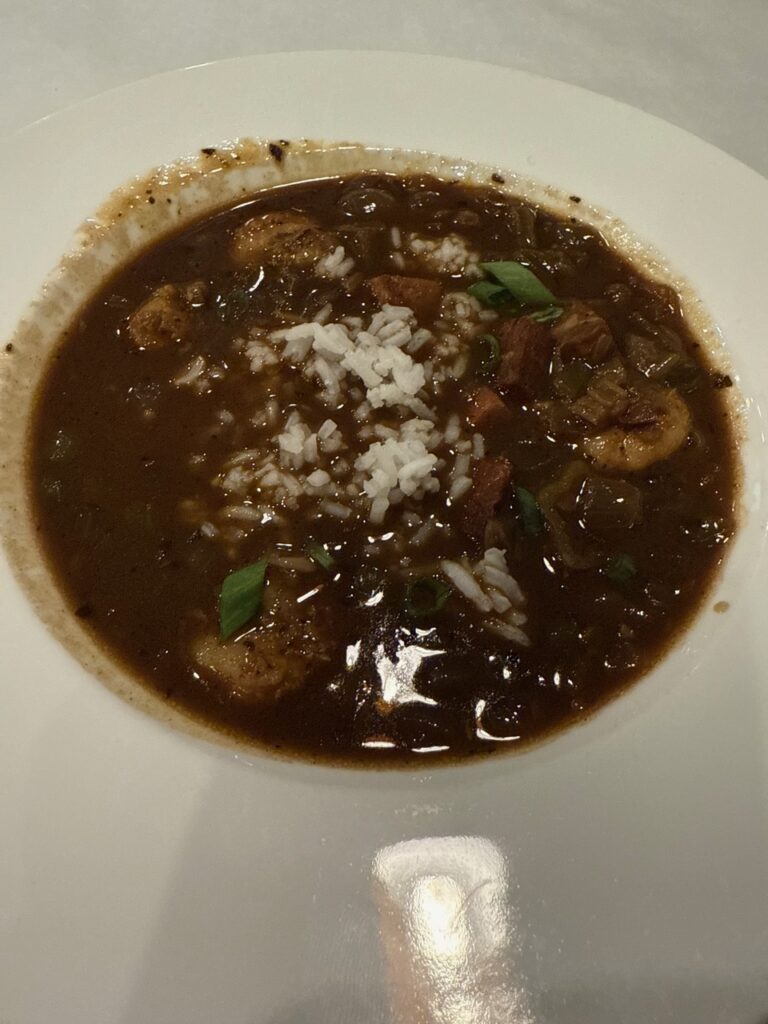

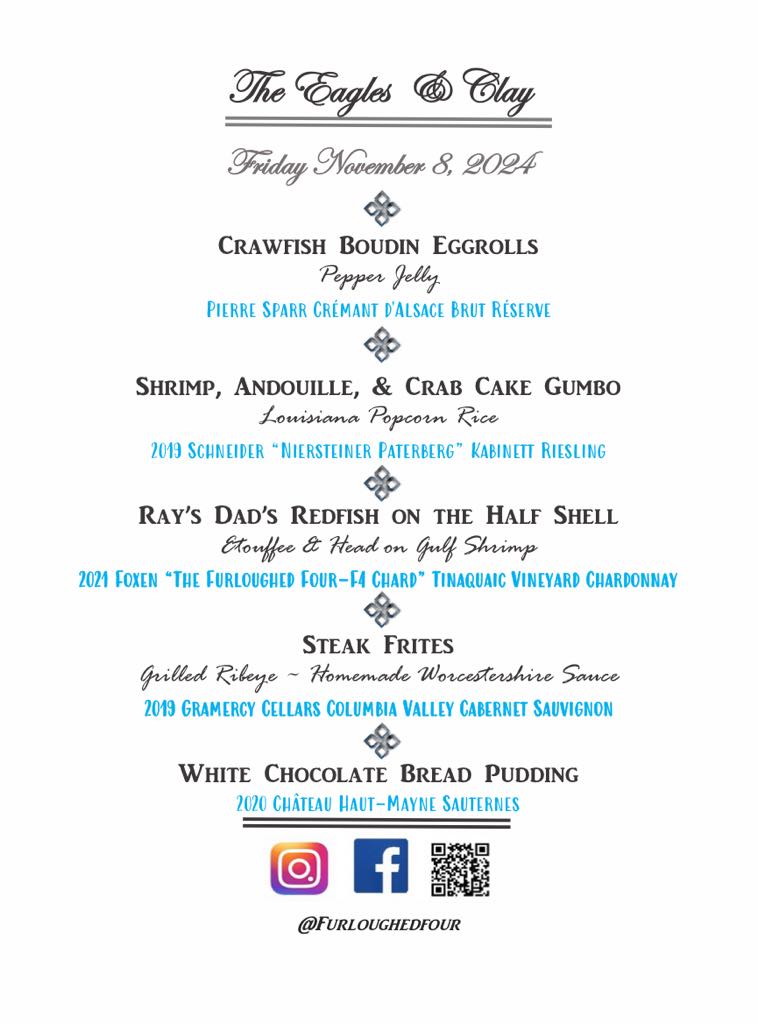

And so another kind of Thanksgiving orgy began. Ray asked us if we wanted to order from the menu or sit back and be fed. Feed us, we said nearly in unison. Boudin egg rolls came first. Then, there were flights of oysters from several origin sites and presentations, coupled with a celebrated local bread, crusty on the outside and oh so smooth inside. Then, a half-shell etouffee redfish caught that very day in some brackish bayou nearby. Steak frites because we were now too sated to eat the full New York strip steaks that were offered to us. And, of course, the celebrated gumbo, or more precisely, crab cake gumbo paired with F4 Chardonnay. The bottles of wine just kept coming, and each was exquisite. Ray appeared from time to time to banter with the table, and he and Russ talked about legendary meals and restaurants they had shared over the years in several states. I wanted to ask him if having the last name Gumpert directed his career choice, and if so, thank goodness his last name wasn’t Spampert. But I held back. Russ and Liz will drive hundreds of miles for these meals and fly across America, too. I won’t even drive across Bismarck for the better of two Thai restaurants. Liz spent half her time that night in MeMe’s gushing about the food and half studying me to see that I was properly humbled, delighted, and satisfied with the world’s premier gumbo. Chef Doug Braselman put in an appearance. We goshed and we gushed.

The gumbo was delicious, dark brown, with a strong hint of vinegar. I tried not to think much about the cost of this meal (staggering), and in my oyster-wine haze, I tried to figure out how vast the tip must come to for such amazing hospitality. Ray has a natural, understated, comic persona, and he told us all sorts of BS about how his father (if he really exists) caught that very redfish earlier that very day and that he, Ray, cleaned it on a table that was really better suited for something else … and other whoppers of that sort. It was a great fish, but my view (stated) was that it was probably purchased earlier in the day at Safeway, and Ray did not take umbrage, perhaps because I was at least half right. He later sent a “video” of someone purporting to be his “father,” with a willow pole and some string at what purported to be a “bayou,” with Andy Griffith whistling in the background. I grew up in North Dakota, Ray. We know our fish tales.

It was, without question, one of the best meals I have ever had. The great food was made better by Liz’s triumphant satisfaction, by two of the great true friendships of my life, by Ray’s wry, generous, and bemused deportment, by the parade of delicacies we had not ordered, by the quality of the wines, by the dark, sensuous atmosphere of MeMe’s, and by some of Ray’s whoppers.

We took an Uber back into the city’s heart in a gumbo coma.

Clay, Liz and Russ’ menu at MeMe’s Bar & Grill — Chalmette, Louisiana. Owner & Chef Doug Braselman, sommelier Ray Gumpert.

Over the next two days I ate gumbo three more times, twice at fine restaurants. It was certainly uncontestably true that Ray’s was the finest. But eating four units of gumbo in three days is a little like eating four units of lasagna in three days. In the end, it is a sausage and shrimp stew, gummed together with mucilaginous okra. I freely acknowledge that Liz was right all along, but I knew that would be true long before I joined the giant carbon footprint grail quest. In the same three-day exploration of New Orleans, I ate etouffee, jambalaya, red beans and rice, a po’boy or two, crayfish, and rice of several hews. Plus enough rich southern desserts to sustain a diabetes clinic.

From now on, I will confine my gumbo life to two circumstances. I’ll either be with Liz somewhere where she deigns to approve of the blend (and where Russ has a longstanding relationship with the chef) and at MeMe’s of New Orleans. I’ll definitely be back. I wrote to Ray suggesting he and I do a series of wry videos in which I — a North Dakotan raised on meatloaf and tuna melt — sample all of his foods and wines while he does explanatory shtick — all I demanded was the experience and a nearby Hotel 5 — but he appears to have changed his cell number after the first 30 texts.

The Gastronomic Wonders Never End

There is much more to the story of my food explorations below the Mason-Dixon Line, but for the moment, just this.

One: in Salisbury, North Carolina, I had my first taste of Cheerwine, a local soft drink that is surprisingly good but has never followed Dr. Pepper and other sodas into the national arena. I’m told there is even an annual Cheerwine Festival in Salisbury that brings in more than 100,000 people. I was warned not to be fooled by the Cheerwine in cans — adulterated somehow — but only to purchase it in bottles, where it is still pure. As I motored out of North Carolina, I had the impulse to stop at a Food Lion grocery and put a few cases of Cheerwine bottles in my pickup bed, the way we used to smuggle Coors into North Dakota in the 1970s before they put preservatives in the mix.

Two: at a mid-day informal seminar at West Texas A&M in Canyon, Texas, a young woman, a student of the humanities studying under the gifted professor Alex Hunt, introduced herself by asking me, “Mr. Jenkinson, what’s your beef with Waffle House?!” She said this with some aggression and considerable disbelief. Apparently, she has been listening to my podcasts — including perhaps the one in which I said the South has made only two contributions to world civilization: Faulkner and Waffle House.

Three: I stopped in Louisville, Kentucky, on my rapid drive home to see the Muhammad Ali Center. It was begun by a friend of mine who now lives in Arizona. Coming off the magnificent but deeply upsetting Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama, that chronicles the tragic history of slavery, racism, and racial violence in America, I wanted to experience the exhilaration of Ali’s meteoric career. Ali says, in his museum, on video, “I didn’t become the heavyweight champion of the world because I loved boxing. I did it because I wanted to get the world’s attention. Now that I have it, I have some things to say.” That’s a slight paraphrase, but it’s very close.

To tell the truth, the Ali Center was a letdown after the Legacy Museum, which is perhaps the finest museum experience I have ever had on a single subject. My friend Thad met me in the lobby, and we saw the exhibits together. Afterward, in the little time he had left before his afternoon meetings, we drove in his car to Muhammad Ali’s grave in Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville. As we paid homage, he told me about the crowds (more than 100,000 people) who came to pay their respects to the flamboyant world historical citizen on June 11, 2016, the man who said, refusing induction into the U.S. Army, “No Viet Cong ever called me N….” Then we stopped at a nearby park on a chilly northern Kentucky day and ate the ham and cheese sandwiches and potato chips he had provided. I wished I had brought a bottle of Cheerwine for Thad and one for me. But no. As we gathered up, he pulled a small styro container with a plastic lid from the bag. In it was some kind of brown slurry. He said it was something called Country Ham Salad. It’s apparently not much different from chicken salad, only darker to look at and inedible. Ham bits, mayo, onion, perhaps a bit of mustard, some relish. Yum.

Will the Southern gastronomic tyranny never end? I promised (a lying promise) that I would eat it for dinner and drove away quickly before he put it in contract (lawyers!). It looked like what’s left over when you strain brown gravy from a turkey or empty the oil in a lawnmower after 10 years. Until now, I had thought my friend Thad, another talented attorney, was a man of elegance and taste.

The next day, in Kansas City, Missouri, I stopped one last time for intentional food — at Chef J BBQ on 13th Street, right on the banks of the Missouri River. My daughter had done a bit of internet sleuthing and assured me that it was the best barbecue in Kansas City. She was right. I entered the gloomy restaurant in an ancient brick warehouse building, puzzled over the large menu. I followed the Russ-Liz rule and asked the chef to tell me what I wanted. Brisket, of course, with three sauces on the side; they also urged me to order collard greens with bits of shredded pork and a healthy dose of vinegar. These were my first collard greens. My daughter had been right. It was the best barbecue I have ever eaten, not just in KC but in America. I hired her on the spot to be my concierge next year when I follow the Lewis and Clark Trail from Monticello to Astoria and back again.

Later that day, after my Amarillo-Turkey-New Orleans-Salisbury-Louisville-Kansas City Vittles Vacation in the American South finally ended, I turned my rig north towards Des Moines, Minneapolis, and Dakota. I had a bland pizza for dinner.

I was never so relieved to pop over the Mason-Dixon Line back into American civilization.