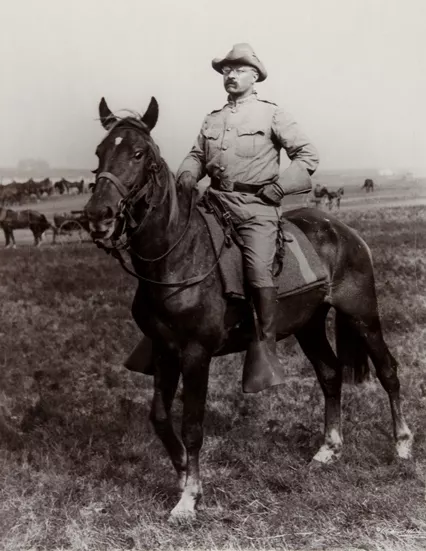

A not-so-rough rider, Clay gave a historical presentation as Teddy Roosevelt during a recent visit to Santiago de Cuba, Cuba.

The day after our arrival in Santiago de Cuba, my cultural tour group charged up San Juan Hill. It doesn’t make sense to come to Santiago de Cuba on the southeastern coast of Cuba without looking at the hill that made Theodore Roosevelt a war hero in 1898. Kettle and San Juan hills are not mountains. They are closer to what Dr. Samuel Johnson called a “considerable protuberance.” You don’t feel heroic looking up at them, but if Spanish snipers with smokeless Mauser rifles were raining down bullets on you, you might feel a little more lionhearted.

I had been encouraged to bring along my Theodore Roosevelt costume. I own several, but in this instance, I wore black jeans, cowboy boots, a fringed buckskin shirt, a Rough Riders hat, and a blue polka dot handkerchief. This is not exactly what Roosevelt wore on what he called “the greatest day of my life,” but it evoked his character and identity.

My outfitter friend Wayne found someone to bring 25 chairs — no easy task in Cuba. They arrived on time and set up right next to the famous surrender tree, where, on July 17, 1898, the Spanish relinquished their centuries-long occupation of Cuba.

For a person who has performed thousands of times before audiences all over America and beyond, wearing a range of strange and often ridiculous costumes (from Grizzly Adams beards to codpieces and Shakespearean earrings), it may seem odd that I am a very shy man and I don’t like to make a spectacle of myself. The thing I dislike most about performing historical characters is the elevator ride in the hotel. I am entirely at ease once I am on stage and voicing my unscripted monologues. I suspend my own disbelief, but earlier, as I board an elevator on the ninth floor and head down to the lobby, my deepest hope is that it doesn’t stop at any other floor and that nobody else gets on. I’ve seen mothers hush their children into a corner as they gape at me in a Victorian silk hat or 17-century, high-piled white wig.

So there I was, hiding at the back of our bus, looking like someone in a high school history skit about Roosevelt and San Juan Hill. It was so hot and humid that my fake mustache — secured with spirit gum — was already threatening to fall off my face. Everyone took their seats, awaiting the imminent arrival of the man who would become the 26th president of the United States.

My cowboy boots were pinching my feet severely, so I wince-footed it up to the concrete slab where I would perform. I was worried about the mobile mustache, but I dutifully told the story, in character, of how TR wound up in Cuba in the summer of 1898.

Something like this:

1. TR believed that all great nations have been warlike nations.

2. TR believed a just war toned up a society, restored virtue and manly values, and purged “effeminacy” from the male population.

3. TR was determined to get into any legitimate war in his lifetime, to prove his manhood and to compensate for his father Thee’s decision not to fight in the Civil War; in fact, Thee hired a proxy to go to war on his behalf.

4. When the USS Maine exploded in Havana harbor on February 15, 1898, TR immediately decided it had been the work of filthy Spanish insurrectionists. So did the “yellow press” in New York.

5. TR was perhaps the most outspoken jingoist in America in 1898.

6. After the Maine exploded, he exerted himself strenuously to get permission to round up a group of “harum-scarum rough riders” as a voluntary cavalry to fight the war in the Caribbean. He defied President McKinley, Secretary of War John Long, his closest friend Henry Cabot Lodge (who said it would be political suicide), and his wife Edith (recovering from a life-threatening operation) to get himself into the war. He later said he would have left Edith’s deathbed to get himself into battle.

7. They trained at San Antonio, Texas but embarked from Tampa, Florida on a crowded, fetid troop ship.

8. After a preliminary skirmish at Las Guasimas, Cuba on June 24, the Rough Riders made their way to Santiago de Cuba with only two or three horses.

9. On July 1, 1898, TR achieved his “crowded hour” when he thrust his Rough Riders forward in front of regular troops and charged up San Juan Hill.

10. TR killed a Spanish soldier with a pistol that had been recovered from the USS Maine. At one point, he shouted, “Look at those damned Spanish dead!”

11. After Spain surrendered, the Rough Riders were quarantined for a month at Montauk, New York on the eastern tip of Long Island. His loyal men gave TR a bronze of Frederick Remington’s Bronco Buster, at which he wept.

12. TR wrote his account, The Rough Riders, which one friendly critic said should have been titled, Alone in Cuba.

13. The rest is history.

I said all that and more in character while my mustache slipped down my upper lip and sweat sprayed from under my hat and buckskin shirt. I took a few questions. At some point, I plucked what was left of my mustache and put it in my back pocket.

Question: Colonel, did you ever soften your view that the Anglo-Saxon peoples have a special managerial destiny in the world?

TR: No. Rudyard Kipling was a friend of mine and we more or less agree.

Question: Did you believe the people of Cuba were capable of self-government?

TR: Certainly not. Not in the short term, not for a long while.

Question: What was your role in the Panama Canal?

This led to a long, boastful answer, essentially that if TR had put the notion to the Senate to debate, they’d still be debating it in our time. He just took the canal zone and built the canal, and the Senate is free to debate him forever!

Sopping wet and half-fainting from the heat (and the pinched boots), I would have gone on for another hour, but Wayne gave me the universal “don’t make me get the hook” gesture, and I broke character, said a few words as a humanities scholar, and withdrew.

A Cuban’s Perspective

That’s when the most interesting part of the morning occurred. A Cuban law professor named Ray came forward. He did not speak English, but our guide and interpreter, Marlin, translated him sentence by sentence and point by point.

Here, in brief, is what he said.

First, the Cuban insurrectionists had nearly won the long war of independence against the Spanish by the time the Yankees swept in seeking glory in the summer of 1898. Second, when the war was won in Cuba, the Americans and Spanish refused to permit the Cuban people to participate in the surrender ceremony under the very tree where we sat. They regarded the treaty as an exclusively major power event. Third, in the end, the Cuban people merely found one colonial empire (Spain) replaced by another (the US), but without true independence. Fourth, even now the Cuban people have very little maneuvering room because of the hostility of the colossus just ninety miles north of Havana. Fifth, he (Ray) must speak very carefully about current events because complete freedom of expression is still impossible, even in post-Castro Cuba.

There was more, but that gives you an idea of his discourse. We all had a very satisfying dinner at his house that evening. When we arrived, I asked our interpreter, Marlin, to say in Spanish, “Thank you for your gracious hospitality. I want you to know that I don’t believe all that s… (stuff?) that came out of my mouth earlier today.” He smiled gently and said he understood it was a historical re-enactment; of course, he had heard it all before.

The people of Santiago de Cuba are deprived of many of the basic amenities of life. We were all advised to bring toothbrushes, toothpaste, soap, shampoo, pens, pencils, etc., from the US to give to Cuban people we came into contact with. They don’t exactly beg — certainly not San Francisco style — but the poorest Cubans made it clear every time we left the hotel that their needs are simple and profound. The following day, I took my black and gray cowboy boots out of the hotel’s front door and an older Cuban woman appeared as if out of nowhere and tearfully accepted them.

Everybody wins.

Roosevelt’s heroics in Cuba seem a little like comic opera 130 years later, but he rightly said that the Rough Riders experienced a higher casualty rate than the regular troops. TR was the most conspicuous person in the battle, virtually alone on horseback, with the Spanish snipers in a much more advantageous position on the hilltop. His bravery is uncontestable, arguably reckless. Afterward, he told his children he had vindicated the family name.

Secretary of State John Hay called it a “splendid little war.” It’s not clear that Roosevelt cared much about the destiny of the Cuban people. He understood more than his closest allies that his participation in the war would be the making of his political career. Still, he would have gone to San Juan Hill even if that little battle would be a forgotten footnote in history. He rightly declared that his stern and strenuous public statements about the need to go to war against Spain might be considered hypocrisy if he stayed behind in a desk job in Washington, DC.

He was a man of his times, but so much more, too, as we are men and women of our times and subject to the assumptions, presuppositions, prejudices, and habits of the arena in which we seek meaning and achievement.