I’ve been a space junkie since I was a boy growing up on the plains of western North Dakota. During the Mercury and Gemini programs, our teachers used to roll in a small television set to the classroom during launches. We’d sit breathlessly through the countdowns, often delayed by hours or days.

I remember coming home from school the day that Gemini VIII astronauts Neil Armstrong and David Scott survived an in-flight emergency when their spacecraft went into a spin that would likely have broken up the capsule or caused their brains to blink out had it continued even a few minutes longer. We held hands in our living room.

At that time, I knew each of the astronauts as we knew each of the Beatles. I could rattle off thrust rates for all of the launch vehicles. I’d sit for hours in front of our black and white TV listening to Walter Cronkite and North Dakota’s favorite son, Eric Sevareid, make commentary during the inevitable delays.

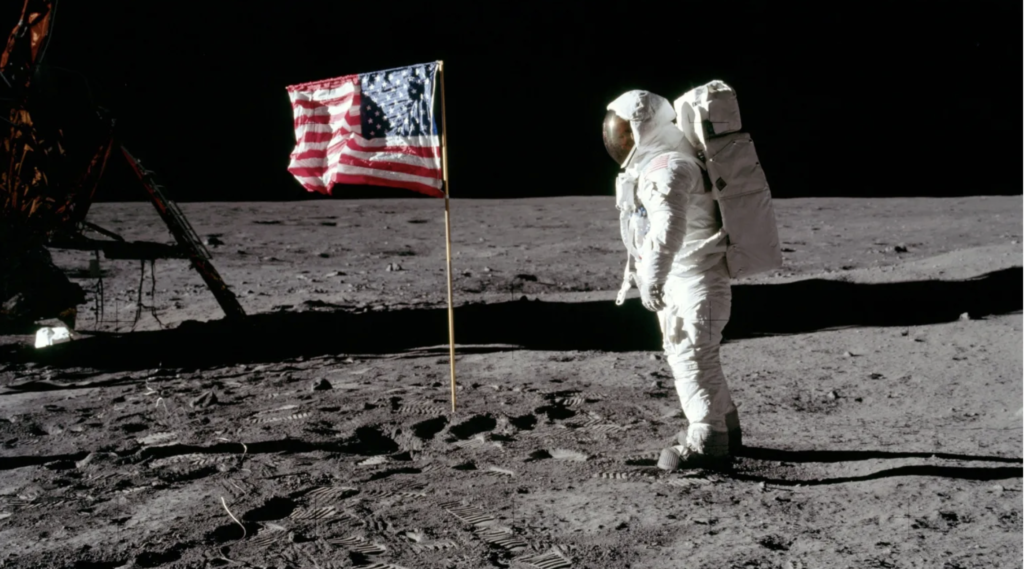

I was walking in downtown Dickinson, my hometown of 13,000, when the Apollo XI Lunar Excursion Module (LEM) touched down on the moon. I watched the coverage of the landing through the window of the “Coast to Coast” store near the bank where my father worked. “Houston, Tranquility Base Here. The Eagle has landed.”

My parents gave me my first 35mm camera for my eighth-grade Christmas. It was the greatest gift I ever received, and it changed my life’s trajectory (note the use of space metaphor here!). Hours before Neil Armstrong stepped onto the moon’s surface on July 20, 1969, I had set up my camera on a tripod opposite the rounded screen of our television. I turned off all the lights in our “den.” I took three rolls of Tri-X B/W film of that first hour on the moon. My sister, who was bored with the whole thing but felt compelled to sit through some of it, made fun of me for my attempt to capture the moment on film. This was before VCRs. Live television came and then went. I was not going to miss the moment.

I still have the photos I took that day. Sometimes, I gaze at them and find myself falling into a vortex of nostalgia for another time in America’s history.

I remember precisely where I was when the Challenger blew up on January 28, 1986. I was in the University of North Dakota student union in Grand Forks. No cell phones, then. I rushed to the nearest pay phone, called my wife at home, and said, “Turn on the TV,” and hung up.

President Ronald Reagan gave one of his greatest speeches that night. What I loved most about it was not the overused “slipped the surly bonds of earth” quotation from John Gillespie Magee’s High Flight, but Reagan’s statement that “I wish I could talk to every man and woman who works for NASA or who worked on this mission and tell them, ‘Your dedication and professionalism have moved and impressed us for decades. And we know of your anguish. We share it.’ ” American presidents are at their best when they inspire, bring the right words of condolence at times of national loss and catastrophe, and honor the great office they hold by exhibiting dignity, decorum, empathy, and compassion.

I vaguely remember where I was when the Columbia broke up on re-entry on February 1, 2003.

My daughter was home for the Pandemic when the first manned SpaceX mission flew on Saturday, May 30, 2020. She was 25. I was 65. We held hands because we wanted it to succeed, the U.S. to return to space under its own rocketry, and hoped there was no fatal setback to that work.

I thought Apollo 14’s Alan Shepard hitting golf balls on the moon was dumb, diminishing the dignity of the moment. Still, I loved it when Apollo 15’s David Scott proved that Galileo had been spot on back in 1589 (possibly 1592) when he dropped two spheres of the same volume but different masses over the lip of the Tower of Pisa.

I’m not sure what to make of Buzz Aldrin’s taking communion on the moon just after they landed on July 20, 1969, but I’m utterly fascinated by that seeming paradox of Newtonian science and the deepest of Christian mysteries, inevitably irrational and “non-scientific,” in such tight juxtaposition.

I was with my family on Christmas Eve 1968 when Frank Borman, William Anders, and James Lovell read the first 10 verses of Genesis from lunar orbit. It was one of the greatest moments of my life, and I still choke up every time I watch the video on YouTube. Even my father, an atheist, could not maintain his composure.

I have a library of about 200 books on the space program, from the birth of rocketry to the recent privatization of space flight, with more coming. I just received and read Tim Peake’s 2023 Space: The Human Story and I pulled down and read Homesteading Space: The Skylab Story. Reading all the space books in one yearlong odyssey of self-indulgence would be fun to get back up to speed.

I was glad that John Glenn got back into space at 77, but I was disappointed when William Shatner booked a ride, especially because he was terrified. So much for James T. Kirk.

I’ve watched all the space movies. There is no substitute for Apollo 13, of course. Tom Hanks IS James Lovell. I watched the first eight or nine episodes of For All Mankind until it got too weird for me. I love The Martian in part because I love Matt Damon and (more) Jessica Chastain. The book is better. But the book is always better. I also love Gravity with Sandra Bullock, even though the dialogue is moronic. No film gives you a more visceral sense of how movement works (or doesn’t) without gravity and an Archimedean place to put your feet.

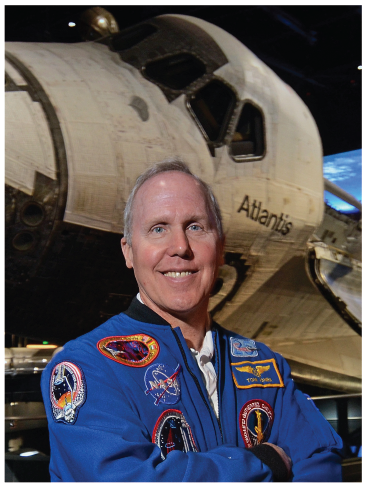

Astronaut Tom Jones (53 days in space) is a good friend of mine. He and I have done programs together where he is astronaut Tom Jones, and I pretend to be Meriwether Lewis, and we answer all the questions: what do you eat? How do you keep records? How was re-entry to everyday life? How do you eliminate bodily wastes? What kind of records or journals did you keep? It was great fun.

And I had the chance to interview ISS astronaut John Phillips while he glided over my head! It was for a 13-part NPR radio documentary on the Lewis and Clark Expedition. We had 20 minutes together. I was in Portland. He was orbiting the planet. And — mirabile dictu — when I asked the last question, where precisely are you now, he truthfully said, “I’m looking down at the Three Forks of the Missouri River in Montana.” I nearly swooned.

If I had the chance to fly to Mars knowing that I could not return, would I?

Instantly, unhesitatingly, absolutely, and with not the slightest regret.

The fascination continues, but it will never be the same as when the Cold War was at its height. The future of humankind seemed to be at stake, and we huddled around grainy black-and-white sets and listened to Walter Cronkite explain what a glorious adventure we were on. I have a huge LEGO model of the Saturn V rocket on a stand in my living room. Sometimes, I sit in front of it and ask myself, would I get into that capsule in 1968 when it had never flown with humans before and the previous two test flights had been problematic?

There is no possible way; before I reply, Suit and beam me up.

Editor’s note: This is the first of two articles by Clay on exploring space. You can read the other here: Space: The Final and Unforgiving Frontier