My lingering impressions from a visit to England.

Eight English Vignettes:

1. Dawn taxi to Heathrow Airport, about 35 minutes from the heart of London. The sunrise conforms perfectly to the poet Homer’s phrase, “rosy-fingered dawn.” Big Ben and Westminster glow golden just across the Thames from our hotel. There is no traffic until we approach Heathrow when traffic becomes a snarl. We roll our heavy (souvenir-enhanced) bags into the terminal, and in fewer than 10 minutes, our bags are safely in the hands of United. There is a 99% chance they will be drifting around the baggage rotisserie when we finally clear passport control in Denver.

I’m disappointed to report that Heathrow handles passengers much more efficiently and kindly than most U.S. airports. When we flew in about 10 days ago, we passed through Heathrow passport control in less than 15 minutes, even though the volume of passengers was huge. Heathrow uses passport scanners. The last time I went through passport control in Denver, the queue (see how British terms seep in!) was an hour and 45 minutes. The desk clerks in Britain are uniformly good-tempered. Security was painless. When is security painless?

Leaving Britain is such sweet sorrow. I think the cultural tour of Literary England was the most satisfying foreign tour I have led. To put it in a nutshell: the British Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, Dr. Samuel Johnson’s house in Gough Square, St. Paul’s Cathedral, the Tower of London, Jane Austen’s in Bath (plus the Roman baths), Stratford-upon-Avon, two Shakespeare performances, an insider’s tour of Oxford University, and a stop in a lovely Cotswold village. All satisfying. But the sorrow is in leaving my daughter asleep in the London hotel. I won’t see her again for months. She is a full adult now in the full stride of her young professional life.

Every time I do this, by which I mean fly from somewhere in Europe to the United States, I marvel at the improbable miracle of modern mobility. I can start the day in London, Rome, or Paris and sleep in my own bed that same night in Bismarck, North Dakota, half a world away. It took Thomas Jefferson 10 days to travel from Monticello in Virginia to Philadelphia, and he had to ford rivers on a horse to get there, stay in appalling inns where the sheets were seldom changed, and often enough, one had to share a bed with a stranger. When the flight attendant on my trips announces that peanuts will be unavailable because some six-year-old has a peanut allergy, we passengers come close to rioting and rushing the cockpit.

2. The American presence in London. Statue of John F. Kennedy. Statue of Abraham Lincoln. Ben Franklin’s house. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was the first American commemorated in Poet’s Corner of Westminster Abbey. T.S. Eliot is also honored there. Though an American born in St. Louis, he was so deeply Anglophilic as to be essentially adopted into the pantheon of English poets. Theodore Roosevelt married (for the second time) in London on December 2, 1886, at St. George’s church in Hanover Square. His best man was the British diplomat Cecil Spring Rice (Eton, Oxford). But who comes to London to look for the American footprint?

3. British pub life is wonderful. Somehow, it’s so different from a typical American bar or tavern that it belongs to a separate category. Most pubs have a number of rooms (often on several floors) lined with dark wood and battered wooden (not synthetic) tables. Pub grub is great. It’s hard to go wrong with a steak and mushroom pie (about the size of an American frozen chicken pot pie, but deeper, and usually served with mashed potatoes and thin brown gravy. You get your beer on tap, and if you want to be authentic, you get it at room temperature. The ciders are finer, drier, and less sweet than their American counterparts. My favorite pub meal is the ploughman’s lunch, which consists of a few inches of excellent baguette bread, a couple of triangles of cheese, some chutney, and a gherkin. Ecstasy. At night, in the quieter pubs, you often see an older man in tweed, an unlit pipe in his mouth, with an older dog lying patiently at his feet. The strangest thing about British pubs is the dense congregation of younger people, mostly but not all men, standing in something like a phalanx out on the sidewalk, each with a pint of beer in his hands, exchanging laughter and pleasant insults. In America, even when we try to imitate an English pub, it still feels like a bar pretending to be a pub.

4. The British countryside is gorgeous: green fields and hedgerows, low unmortared stone fences, sometimes with stiles (wee conjoined wooden ladders on either side). By American agricultural standards, everything is on a miniature scale. Most of Great Britain is hills and dales. There has been way more than average rain in the last few months. The rivers are all overflowing now, but it doesn’t feel like flooding because the British factor in and preserve riverside marshland, except along the lower Thames where the Victorians engineered impressive embankments to protect the city of London. In Stratford, there are swans and ducks, but it is the swans that are poetic.

Shakespeare gets it right in John of Gaunt’s deathbed encomium to England in Richard II: “This other Eden, demi-paradise … this precious stone set in a silver sea … this blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England!” As we motored out of Bath towards Oxford and glimpsed the irregular patchwork quilt of fields running up and over the hillsides, stone barns, and neoclassical houses (which seemed like manors), several of our guests gasped at the almost impossible beauty of the English countryside. Sheep everywhere. The English cattle are placid — in a land of abundant rain and excellent pasture, they know nothing of the harder life of American cattle, who endure harsh winters and periodic droughts on their wild, semi-arid landscapes. There is nothing like the English countryside in the United States, not even in Quebec or Vermont. As we drift through the British countryside, it feels like some dream of England rather than the real thing.

5. The butter and the bread and cheese are perfectly delicious. Why, America, why? How can we be the wealthiest nation on earth, with the largest wheat harvest of any nation, and yet manufacture (perhaps that’s the key word here) such inferior butter, bread, and cheese?

6. Wandering about Great Britain makes you want to read through the Norton Anthology of English Literature. Everywhere you turn around, you bump into a writer’s house or one of those blue disks affixed to a modern bank building or shop saying, “James Joyce lived here between x and y,” or “Bertrand Russell’s mistress Lady Ottoline Morell lived here with her husband between z and w.” I studied English literature at at least three universities in my time, including one in Britain, so the lens I wear may be inordinately fixed on writers. When I studied in England, you could go into almost any little shop (sometimes called a “tuck shop”) and find the complete works of Jane Austen or Dickens or George Eliot on a rack that in America would feature James Patterson or Louis L’Amour (not, as Seinfeld says, that there is anything wrong with that!). I bought some books of literature and literary criticism at two of the greatest independent bookstores in the English-speaking world, one of which is Blackwells on Broad Street in Oxford, and took smartphone photos of a dozen more I ordered from our London hotel on Amazon.com (another marvel of modern technology), which will be waiting for me when I reach my home later tonight in Bismarck. In London, we took a group photo in front of the recently restored Old Curiosity Shop, one of London’s (and Britain’s) oldest shops, dating from the 16th century (which is when Sir Walter Raleigh’s ships (not much more than yachts) were exploring the Outer Banks in today’s North Carolina and naming the east coast of America “Virginia” after the Virgin Queen Elizabeth I.

7. We visited the British Museum twice. Because on our first visit, we discovered — to our extreme disappointment — that the famous Elgin Marbles, now referred to as the Parthenon Marbles, were “closed for maintenance.” I’ve been through the British Museum a couple of dozen times in my life, and I always rush first to Room 18, which houses the statuary removed from the Parthenon in Athens by Lord Elgin in the first years of the 19th century and later purchased by the British parliament. This was the first time in my experience that the treasures of the Parthenon were closed to the public. I had built them up in my commentaries in hotel meeting rooms and on the coach, and my daughter and I had conducted a mock debate over whether the marble sculptures should be returned to Greece, which insists that they be repatriated.

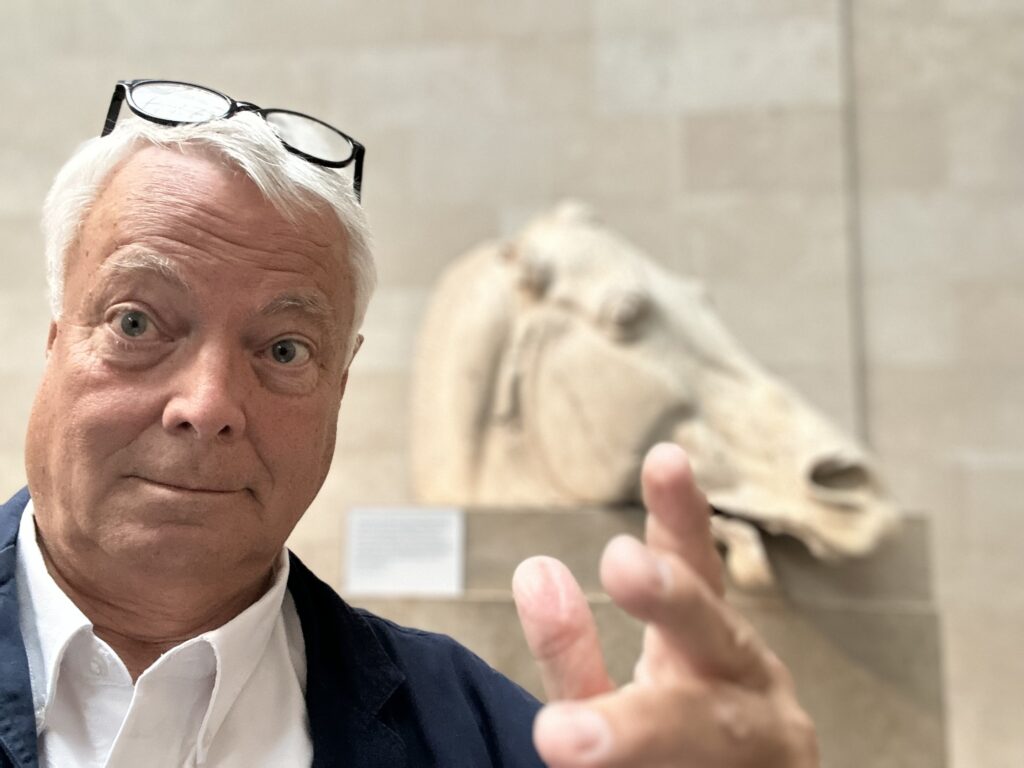

So we carved out time for a second visit on our last day in England. I rushed to Room 18 ahead of the pack and to the Horse of Selene, looted by Elgin from the east pediment of the Parthenon. I tried to remember my first sight of that sculpture decades ago, when I stood in open awe before a perfectly realized horse visage lovingly coaxed out of a block of stone by craftsman who lived 2,500 years ago. At our best, “what a piece of work is man,” as Hamlet puts it in Shakespeare’s greatest play. I’m not much for selfies, but I’ve had my photograph taken there every time I visit the British Museum in a “same time next year” protocol. But the spontaneous inrush of wonder and pure admiration I felt 40 years ago when I stood before that horse cannot be rebooted now: as we age (most of us), we lose some of our capacity for wonderment, for an ability to surrender to the sublime in art, music, literature, friendship, and love. There can only be one first kiss. Now there is too much wear and tear on my aesthetic and spiritual tires. My synapses of wonder and my spiritual arteries are somewhat clogged. Now, when I stand before the Parthenon Marbles, I have to self-consciously crank up my sense of wonder like a music box or cream separator, and I sense the strain as I try to feel what I once felt. It’s tragic, one of the hardest things to accept in life.

As I stood there trying to be fully present — PRESENT — I found myself asking when would be the last time I stood there, halfway across the world. Perhaps this was that time. I don’t think so, but we as a civilization have entered a new age of disruption (pandemics, cyber attacks, drone wars, decolonization, and postmodernism), and my life is well over half over.

8. One of my favorite moments from the journey was outside the Jane Austen Centre in Bath as a light rain fell on wet pavement. There is a full-size statue of Ms. Austen outside the door of the museum, wearing a sky blue dress that covers all but the tips of her shoes, and a deep navy blue hat with a big white bow. Very Jane Austen! As I stood waiting for the last of our group — for some, the visit to Austen-land was the highlight of the journey — a Muslim family of six emerged from the Centre, the women covered with the hijab. One of them, a young woman, perhaps 19 or 20 years old, looked around a bit apprehensively and then removed her long, slick black raincoat and handed it to her father. She was wearing an identical blue full-length dress, a Jane Austen dress! She stood next to the statue of the author of Pride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility, Persuasion, and three other novels while two members of her family took her photograph.

I was so deeply moved that I nearly burst into tears. I wanted to ask the family if I could take their photo in front of the Austen statue, but I didn’t — it wasn’t my place to interrupt. But this moment did awaken my sense of wonder: at globalism, at Austen’s universal cross-cultural appeal across some wide cultural divides, at the multiculturalism of 21st century Britain, at the self-conscious boldness of the young woman, at the lovely indulgence of her family, at the risk she took (on several levels) in preparing for the day by dressing like Austen and then having her photograph taken at this cultural ground zero. I’ve read my Austen. On the surface, you would not predict that Mr. Darcy, Elizabeth Bennet, and Lady Catherine de Bourgh would be Islamic fare, but what a ridiculous and arguably Euro-centric thing that is for me to think.

It’s obvious. We share more than that which divides us. Although we run different cultural softwares, all humans want much the same thing: security, family, friendship, love, beauty, stories, adventure, and modest prosperity including a bit of excess cash to seek out seemingly inessential pleasures.

Epilogue

All things must pass. I started this dispatch at 38,000 feet in a Boeing aircraft that flew 4,685.71 miles from London to Denver over Greenland and Hudson Bay, and I finish it now in Bismarck, North Dakota, where the mores of Great Britain seem a very long way away. We do have what purports to be an Irish pub, where you can eat Irish Stew or Shepherd’s Pie, but not a Ploughman’s Lunch. My luggage did not make the turn from Denver to Bismarck, but I did receive a text from the airline telling me not to worry; the bags would turn up “on a later flight.”