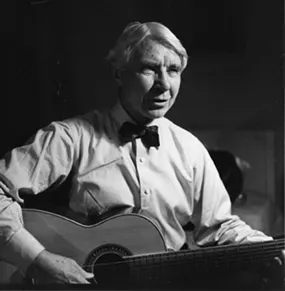

The award-winning biographer, journalist, historian, children’s author, poet, and singer found his calling as a young man by hitting the road and listening to America.

The city of Asheville, which sits at the confluence of the French Broad and Swannanoa Rivers in North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains, boasts a rich literary tradition. Most notably, it appears as Altamont in native son Thomas Wolfe’s autobiographical novels Look Homeward, Angel and Of Time and the River. Wolfe is buried in nearby Riverside Cemetery, his grave a mere stone’s throw from that of another native Tar Heel, the short story master O. Henry. On the city’s north side, at the historic Grove Park Inn, Scott Fitzgerald famously spent much the late 1930s, destroying what remained of his life and talent with drink. Zelda Fitzgerald would meet her demise in Asheville as well, perishing in a 1948 fire at a local mental hospital.

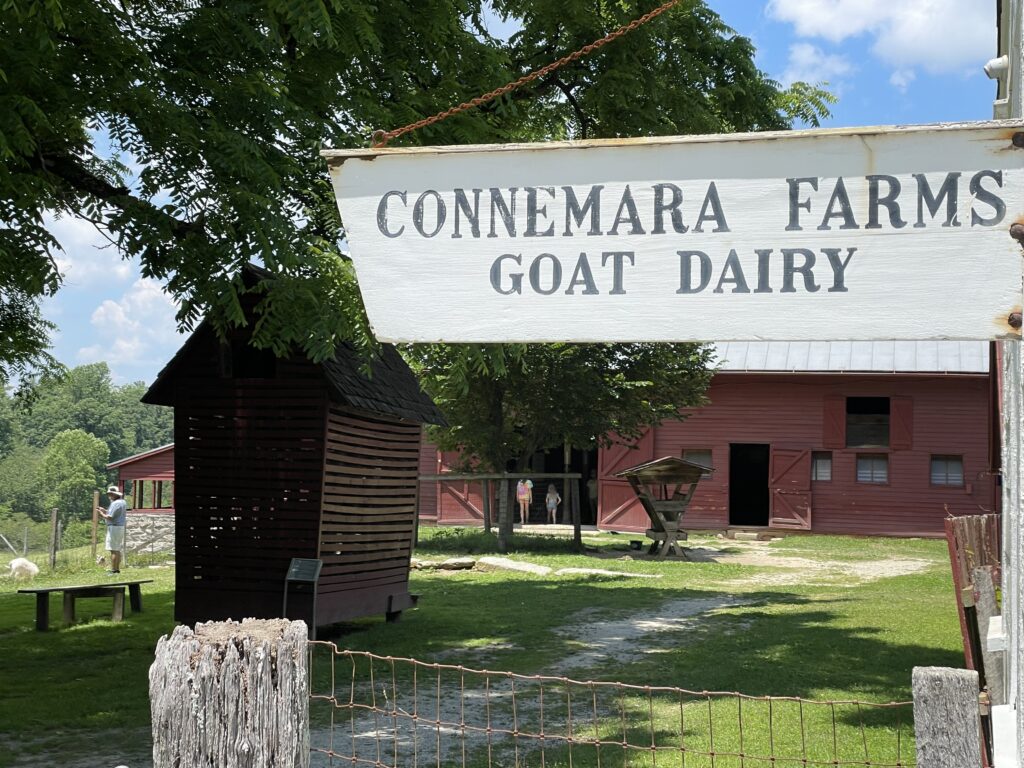

Wolfe’s titular angel still stands in neighboring Henderson County, 25 miles to the south. It’s just a few miles from Flat Rock, a tiny village that’s included on the National Register of Historic Places. Flat Rock’s prime attraction is Connemara Farms, a 245-acre property known familiarly as the Carl Sandburg house. Connemara, which is managed by the U.S. National Parks Department, features lakes and ponds, mountains and trails, an amphitheater, and an historic and working goat farm. Though it carries a rich history dating back to the Civil War, Connemara is primarily remembered today as the home where Sandburg, who died in 1967, spent the last 22 years of his life.

“It is necessary now and then for a man to go away by himself and experience loneliness; to sit on a rock in the forest and to ask of himself, ‘Who am I, and where have I been, and where am I going?’”

Carl Sandburg

Sandburg was born in Illinois in 1878. Growing up, he knew people who had known Abraham Lincoln, a circumstance that would deeply affect and even drive his career. He left school after the eighth grade, and hit the road at age 19 for the life of a hobo, gathering experiences across the country and working periodically on farms and railroads. The young Sandburg developed a habit during these years that he never discarded, that of listening to the voices of common Americans. Sandburg did not find fame until he reached his 40s, first as Lincoln’s biographer, then as the author of a book of children’s tales titled The Rootabaga Stories, and finally as both poet and folk singer. Though his folksy style was not without its detractors — Robert Frost once described him as “the most artificial and studied ruffian the world has had” — Sandburg was widely acclaimed as America’s “poet of the people.” In 1936, at the height of the Depression, he published The People, Yes, a book-length, simple-language epic that celebrated the resilience of the American people.

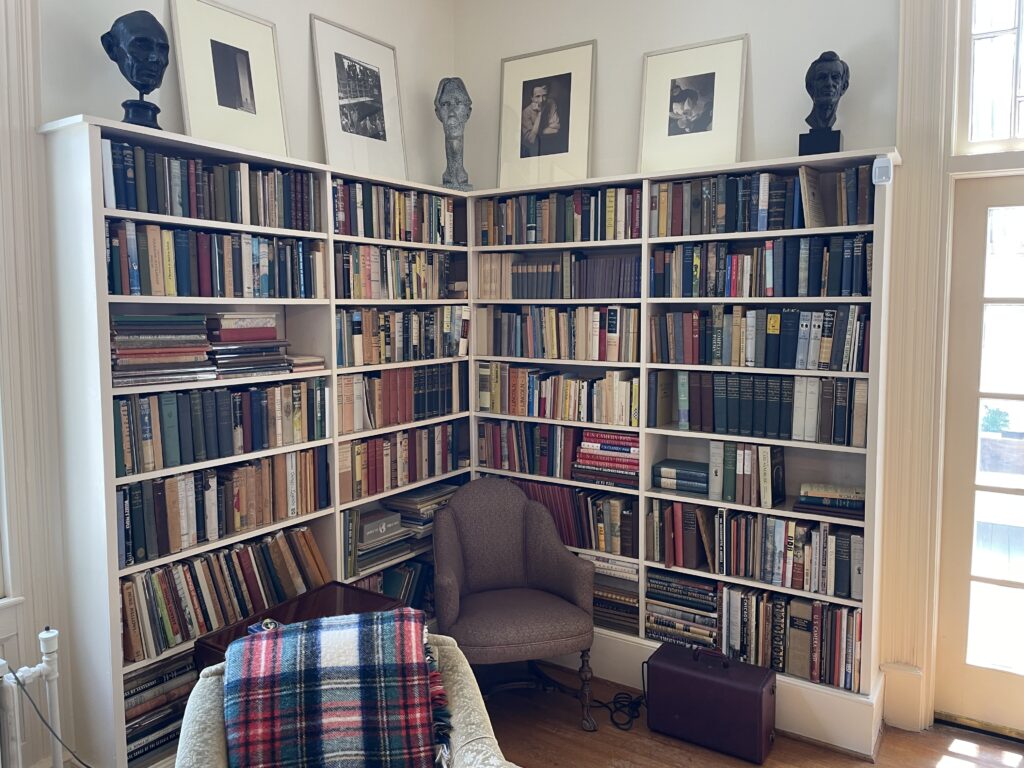

Sandburg is associated mostly with Illinois and Michigan, yet he produced more than a third of his professional output after settling at Connemara Farms. The family’s motivation for moving south was twofold. For Sandburg, it was a search for seclusion, for the ideal place to write. For his wife Lillian, whom he called “Paula,” it was the quest for a more temperate climate for her prize-winning goat herd. The couple purchased the farm for $45,000. An entire railroad boxcar was required to move Sandburg’s 15,000 books from the couple’s previous home in Michigan.

Though Sandburg was 65 at the time of the move, the years in Flat Rock were among his most productive. More than a third of his life’s work came out of his upstairs study in the 7,700 square foot farmhouse. He won the last of his three Pulitzer Prizes during this period, along with a Grammy Award for a Spoken Word Album and the Presidential Medal of Freedom. He continued to travel widely, even visiting Moscow in 1959 as an envoy for the U.S. State Department. He became the first white man ever honored with the NAACP’s Silver Plaque Award. When he died in 1967, President Lyndon Johnson remarked that “Carl Sandburg was more than the voice of America, more than the poet of its strength and genius — he was America.”

Sandburg’s widow left Connemara soon after his death, selling the farm to the U.S. government. In addition, she donated the house and all of its contents. The Sandburg family worked for years with park staff to curate this collection so that when you visit today, you walk through the house convinced that Carl and Paula are still in residence. Perhaps they went out for a short walk in the surrounding hills — you almost look for them to come through the door, or perhaps to call on the black rotary phone that hangs near the dining room. Sandburg’s books line the walls, in the same locations and on the same bookshelves where he left them decades ago, bookmarks intact. His final newspaper remains by his favorite chair, as does the day’s mail. Even the author’s last, half-smoked cigar sits by his place setting at the head of the dinner table. The overall effect is stunning.

There is a lot to do at Connemara. Five miles of hiking trails traverse the property. They range from relaxing woodland and lakeside strolls to the 1.2 mile climb to the 2,783-foot summit of Glassy Mountain. The goat farm is open to visitors, and two films on Sandburg are available for viewing in the old garage behind the house. Performances of Sandburg’s Rootabaga Stories are staged periodically at the amphitheater. But the compelling reason to visit Connemara is the main house. That is where you encounter what has to be the most intact and complete representation available of the daily routine and the lifetime accumulations of a hard-working, award-winning American writer. If you do nothing more than peruse the titles of the house’s 16,000 volumes, noting of the breadth of categories, the meticulous organization, and the thousands of bookmarks, you will leave Flat Rock with an intimate and memorable glance into a man who, by hitting the road and listening to America, etched a place in history as the People’s Poet.