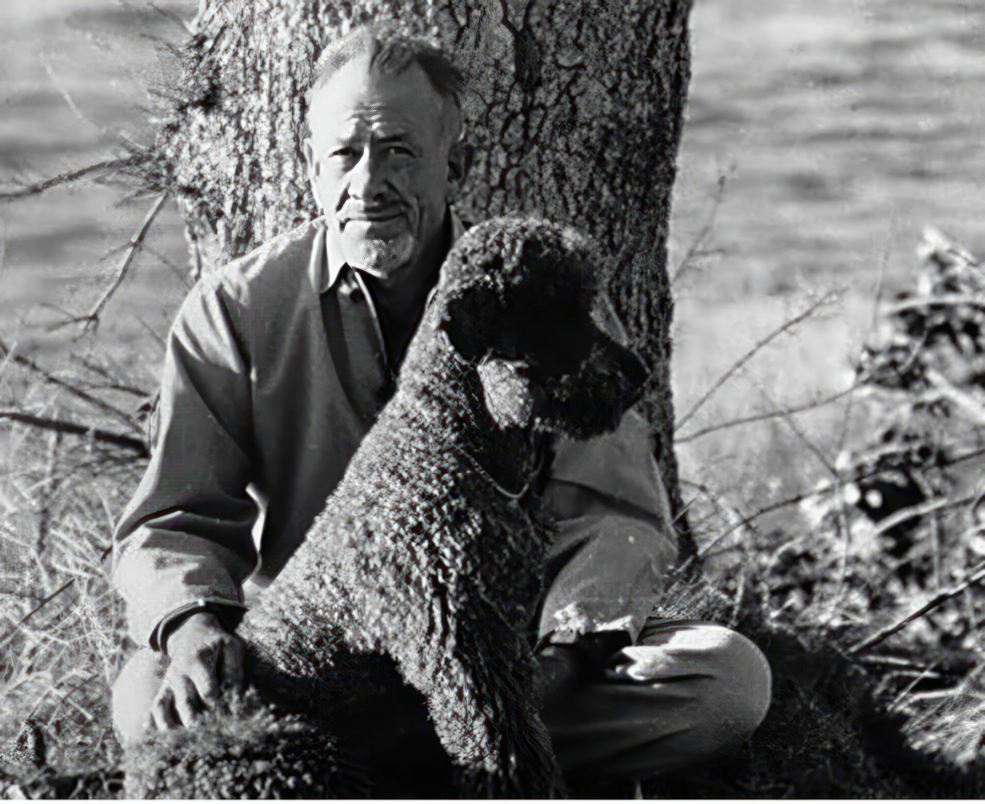

As Clay begins his great Travels With Charley journey, our resident Steinbeck specialist, Russ Eagle, weighs in on what spurred the Nobel Prize-winning author to take to the road in a custom truck camper and his dog in 1960.

Privately, the author saw his famous trip with his dog Charley as “a frantic last attempt to save my life.”

“I had not felt the country for 25 years,” John Steinbeck writes in the early pages of Travels with Charley. For a man known worldwide as an American writer, this was “criminal” the author admits and he declares atonement for this sin as the primary motivation for his trip around the U.S. in the fall of 1960.

Steinbeck’s plan to feel the country was to drive the perimeter of the United States in a truck camper he called Rocinante. The three-month journey would carry him 11,500 miles from Sag Harbor on Long Island, to Monterey, California, and back again.

Steinbeck’s biography offers little reason to dispute this claim. After spending much of the late 1930s traversing the hills and valleys of central California in an old bakery wagon with an old mattress tossed in the back, living and working alongside migrant workers, Steinbeck retreated into the Santa Cruz Mountains in 1938 to write The Grapes of Wrath. The success of that effort made him a rich and famous man, and it changed his lifestyle immediately and permanently. When he and his poodle Charley hit the road two decades later, his life centered around a high-rise apartment on New York’s Upper East Side and a fishing cottage on Long Island. He still traveled often, but mostly overseas. When Steinbeck did travel within the United States, he confessed, it was generally to dip in and out of Chicago or San Francisco by plane.

However, Steinbeck hints at a second “secret” reason for taking this journey a few chapters into Travels with Charley. His health had been failing for years, and he had entered that phase of life where both spouse and physician were urging him to slow down. For a man who had “always lived violently, drunk hugely, eaten too much or not all, slept round the clock or missed two nights of sleeping, worked too hard and too long in glory, or slobbed for a time in utter laziness,” this too was unacceptable. Steinbeck saw the prospective hazards and hardships of his impending trip around the U.S. as “the antidote for the poison of the professional sick man.” He needed to prove to himself that he could still do it. Otherwise, he declared, it was “time to exit the stage.”

This despondency was Steinbeck’s primary motivation for setting off from his Sag Harbor home on September 23, 1960. The key evidence is a letter he had written to his literary agent, Elizabeth Otis, earlier that summer. Before looking at the contents of that letter, it is essential to recognize the role that letter writing played in Steinbeck’s life. He always considered himself a writer: not an author, not a novelist, not a playwright, not a scriptwriter, not a journalist — though at times in his life he was all of these things — but simply a writer. He wrote practically every day of his adult life, and he warmed up each morning by writing letters. He wrote thousands of letters, probably tens of thousands, many of which are extant. Some remain in private hands, but many are available in research libraries and institutions. Nearly 900 were edited and published in 1975 as Steinbeck: A Life in Letters.

This trove includes letters to family and friends, publishers, other writers, presidents and first ladies, celebrities and unknowns. Many are formal or merely informational, but a few recipients stand out as essential confidants across the entire course of Steinbeck’s professional career. Primary among these are his long-time editor, Pascal Covici, and his trusted agent, Elizabeth Otis. Otis was his most consistent and essential confidant, the one he often turned to in times of crisis. Their correspondence across 35 years is a Steinbeck mini-biography of sorts.

When Elaine and others endeavored to talk Steinbeck out of attempting his journey, it was Otis that he turned to for help. In a lengthy letter that appears on pages 668-670 of A Life in Letters, Steinbeck laments that he has reached the point in his life where he can be talked out of things. He desperately wants to make the trip, which he was calling Operation America at the time, but fears he will “succumb to better judgments, and in doing so tear the whole guts out of the project.”

Steinbeck begins the letter with a defense of various aspects of his plan: his mode of travel, his insistence on going alone, and the necessity of traveling incognito. But then he gets serious. “I am trying to say clearly that if I don’t stoke my fires and soon,” he writes, “they will go out from leaving the damper closed and the air cut off. … Between us — what I am proposing is not a little trip or reporting, but a frantic last attempt to save my life and the integrity of my creative pulse.” We find some of Steinbeck’s best writing in his letters. And, as this missive to Otis reveals, some of his most poignant.

“If there is a seething in this letter, do not mistake it for anger,” Steinbeck assures Otis. “I don’t know that my way is right but only that it is my way. And if I have had the slightest impact in the world, it has been through my way.” He closes in verse:

“The stilling mind

“Cries like a kettle in the window crack.

“The house layered with shining cleanliness

“Is set and baited for new guests,

“And the sloven heart of the kind in name

“Is dusty as a beaten rug in its beating.

“How much is required? How little needed?”

The letter served its purpose. Otis wrote to Steinbeck’s worried spouse and managed to soothe her qualms about the proposed journey. Steinbeck followed up a few days later with a short note to Otis. “Your letter made a very great difference,” he wrote. “Elaine, with your backing, which in our house amounts to public opinion, was dead set against my going until your letter … It made all the difference.” Elaine did maintain a single demand: that Charley must come along on the road with Steinbeck. Her insistence on that point proved fortunate, not only for the author but for generations of readers.