Two posthumously published journals provide readers with an intimate look at the creation of the author’s two heftiest volumes.

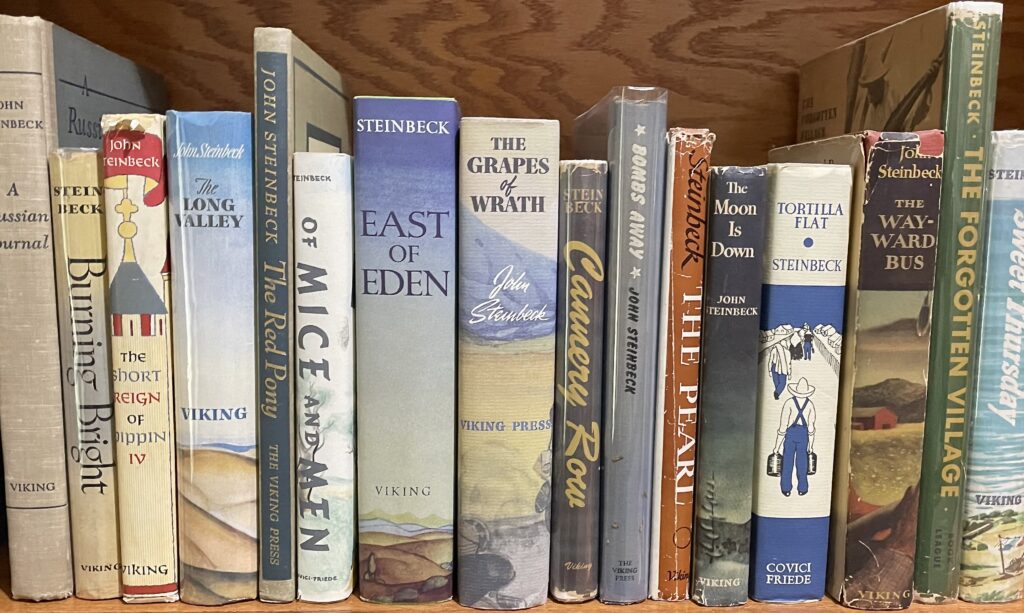

Though John Steinbeck produced some of the 20th century’s most enduring short novels – Of Mice and Men, The Red Pony, The Pearl, Tortilla Flat, Cannery Row — he would grow concerned if he went too long without producing what he called a “big book.”

Books, he said, were like wedges driven into the reader’s personal life, and a short volume was in and out of the consciousness too quickly to have a lasting impact. A longer work, on the other hand, “drives in very slowly … and remains for a while” so that “the mind cannot ever be quite what it was before.”

Examining Steinbeck’s fiction through such a lens, two formidable “wedges” are readily apparent — The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden. While the former is almost universally accepted as Steinbeck’s masterwork, the author himself preferred the latter. He maintained that East of Eden was the one work for which all the others were merely practicing. “I think perhaps it is the only book I have ever written,” he wrote to his longtime editor and friend, Pascal Covici.

For Steinbeck, anonymity was essential for a writer. He worked long and hard to maintain his privacy. When a publisher of one of his early works requested biographical information, Steinbeck responded, “I can’t say how much I wish this kind of thing weren’t necessary.” He maintained that stance throughout his career, avoiding speeches and public appearances and generally declining or ignoring awards and recognition. He did what he could to trip up future biographers as well, burning caches of letters and manuscripts. Fortunately, these efforts were not wholly successful. Great repositories of Steinbeck journals, letters, manuscripts, photographs, and ephemera dot the country. The writer himself admitted to a friend in 1962 that “I’ve left a lot of tracks.” Among the materials Steinbeck couldn’t bring himself to destroy were the journals he kept while creating his two “big books.” Each provides a rare, intimate snapshot of Steinbeck at a critical time in his personal and professional history. Written 12 years apart, the differences are striking at times.

Actually, if there has been one rigid rule in my books, it is that I, as me, had no right in them. And if that is so of the text, let it be so of publicity. You really don’t need me in it. If you do — then book is a failure.

Steinbeck to his Editor, Pascal Covici

Steinbeck famously wrote The Grapes of Wrath in a 100-day sprint in the summer and fall of 1938. This fevered burst of work followed several years of research and a few false starts, including one completed novel that Steinbeck tossed into a fire. He was an angry man while researching and writing The Grapes of Wrath, determined to “put a tag of shame on the greedy bastards who are responsible for this [the migrant crisis in California].” Steinbeck was incensed when the management at Viking Press suggested changes to the ending that might better “satisfy” readers. “I’m not writing a satisfying story,” he fired back. “I’ve done my damndest to rip a reader’s nerves to rags — I don’t want him satisfied.”

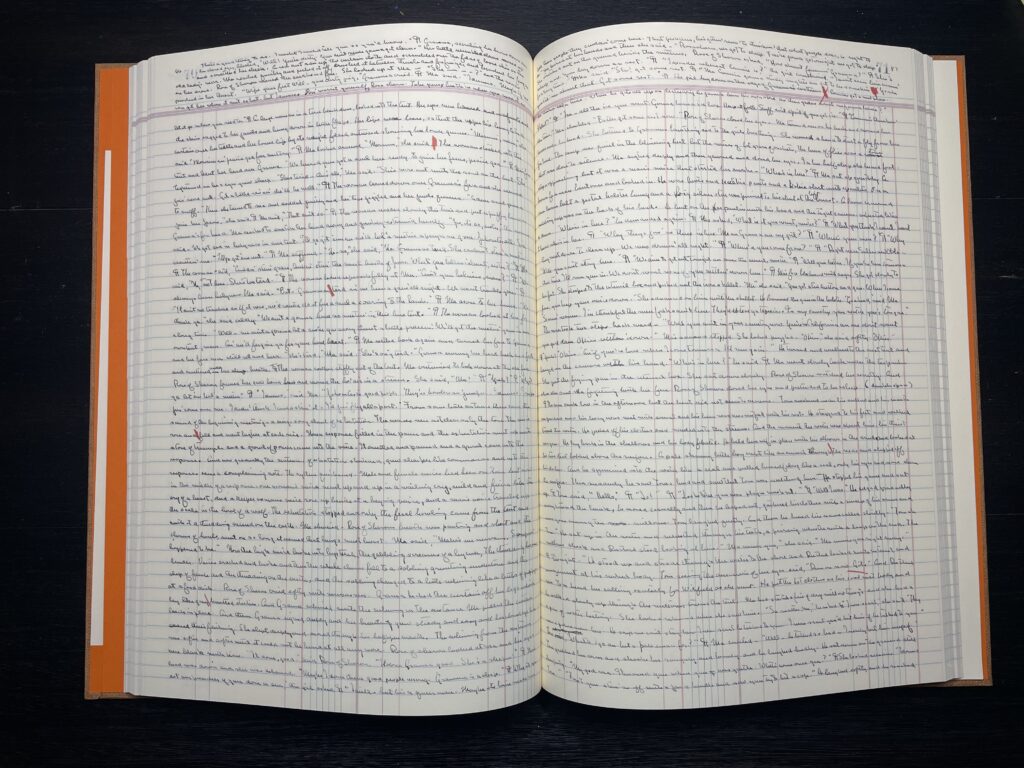

The holograph manuscript of The Grapes of Wrath is housed at the University of Virginia’s Alderman Library and is a sight to behold. Steinbeck’s growing rage leaps off the 83 double-sided, 10″ x 16″ ledger pages. As he gains momentum, the words seem to overwhelm the page. He fills the lined portion of the first sheet with 46 lines and 648 words. By page 19, he is also filling the margins, squeezing nearly 900 words onto a sheet. On page 34, he abandons paragraphing and writes in a single continuous stream. Sometimes, he inserts a ¶ to signify a new paragraph, but he often just keeps rolling. By the time he approaches the end of his story, Steinbeck is squeezing as many as 1,300 words onto a single page. It is a stunning piece of work, even more so when you realize that this first draft became, with no significant changes or revisions, the published novel. John Steinbeck, we might say in modern parlance, was “in the zone” in that summer of 1938.

Unfortunately, spending time with that manuscript is not practical for most readers. Far more accessible is Working Days: The Journals of The Grapes of Wrath, an exciting document in its own right. Throughout this account, Steinbeck finds himself straining under the weight of his subject matter. “This must be a good book,” he implores himself. “It simply must. I haven’t any choice.” But he staggers at times — his confidence wavers. Personal and professional distractions abound. He wonders if he is headed for a nervous breakdown. And yet, his intensity never wavers. “If only I could do this book properly, it would be one of the really fine books and a truly American book,” he writes in late June. Finally, in his last week of work, Steinbeck becomes convinced that he has failed. “I am sure of one thing — it isn’t the great book I had hoped it would be,” he says in the journal’s most poignant entry. “It’s just a run-of-the-mill book. And the awful thing is that it is absolutely the best I can do.” Working Days, in part because it was never intended for publication, offers a moving and highly personal account of the turbulent period from which some claim Steinbeck never fully recovered. Reading through the journal more than a decade later, Steinbeck was particularly struck by the complete lack of complacency in his life. “It has been very high and very low,” he told Covici, “but rarely has it moved gently on calm waters.”

For the first time I am working on a real book that is not limited and that will take every bit of experience and thought and feeling that I have.

Steinbeck in Working Days

A lot happened to Steinbeck after The Grapes of Wrath. Though the aftermath brought fame and fortune, it also brought illness and depression. His first marriage crumbled. Over the next decade, he would remarry, become a New Yorker, suffer serious mental and physical injury in World War II, father two sons, lose his best friend and collaborator Ed Ricketts in an accident, go through a second painful divorce, and see his critical reputation plummet. He was a severely depressed and damaged man when, in 1949, he met Elaine Scott. Their marriage in late December of 1950 was a turning point for Steinbeck, “a new life and a direction.” He was ready for another “big” book. Just a month and a day after the wedding, he eagerly embarked on East of Eden. “Now that I have everything,” he said, “we shall see whether I have anything.” His theme did not lack for ambition. Initially addressing the book to his sons, he set out to “tell them one of the greatest, perhaps the greatest story of all — the story of good and evil, of strength and weakness, of love and hate, of beauty and ugliness.”

The holograph manuscript for East of Eden is housed at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas. Steinbeck again worked in a large notebook — 10 3/4″ x 14″ — though he confined the novel’s text to the right-hand pages. The left-hand pages were reserved for daily letters to Covici. This time, the manuscript served more as a conventional first draft. The Ransom Center’s archives contain folder after folder of insertions, deletions, and discarded pages. This time, it is Steinbeck’s struggle rather than his fervor that permeates the pages. It’s a reminder that The Grapes of Wrath manuscript was the exception and not the rule.

Steinbeck knew that the letters to Covici told a story as well. As with the earlier journal, he left his permission for posthumous publication, and Viking Press wasted little time. They brought out Journal of a Novel: The East of Eden Letters within a year of Steinbeck’s death. In the intervening half-century, it has remained a popular and oft-quoted work. Steinbeck ruminates throughout on the joys and terrors of creation, offers clues to the symbols and themes of his developing novel, and obsesses over the tools of his trade. And he acknowledges a new perspective:

For many years I did not occur in my writing. But this was only apparently true — I was in them every minute. I just didn’t seem to be. But in this book I am in it and I don’t for a moment pretend not to be.

Journal of a Novel: The East of Eden Letters

As with Working Days, there are bittersweet moments. “The book dies a real death for me when I write the last word,” Steinbeck says as he nears the novel’s completion. “I have a little sorrow and then go on to a new book which is alive. The line of my books on the shelf are to me like very well embalmed corpses. They are neither alive nor mine. I have no sorrow for them because I have forgotten them, forgotten in its truest sense.

Steinbeck was being truthful here. He was rarely inclined to revisit his past works, always looking ahead to the next project, be it big or small. In both Working Days and Journal of a Novel, however, he generously allows us to look back on our own at the hopes and dreams he once held for the “big books” in his career.

Over the next few months, Clay is shadowing Steinbeck’s 10,000-mile trek around the USA (and making a few detours of his own). Clay’s expedition is a central part of LTA’s big initiative to explore the country and take the pulse of America as it approaches its 250th birthday. Be sure to follow Clay’s adventures here and on Facebook — and subscribe to our newsletter.