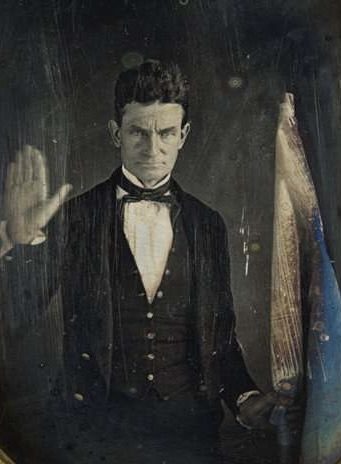

Hero, terrorist, martyr or madman? The dramatic life of John Brown.

For the past couple of weeks, I have been getting to know the story of John Brown (1800-1859). I did this by reading chapters of books about the lead up to the Civil War, histories of Kansas, the whole of Tony Horwitz’s Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid that Sparked the Civil War, several documentary films, timelines and encyclopedia articles; scholarly articles available on JSTOR. That sounds like hard work, but the subject is so fascinating that it felt more like a pleasure to do the reading and note-taking. And I’m just getting started.

We all know that John Brown led an assault on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry in 1859, then in Virginia. The assault failed. Brown was quickly convicted of three counts: treason against Virginia, inciting enslaved people to revolt, and murder. He was hanged on December 2, 1859, 47 days after the failed insurrection. We know, too, that Brown had something to do with the border war in Kansas after the passage of the disastrous Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which permitted each new state to decide if it wanted to enter the Union supporting slavery or slave free.

We know, too, that “Old John Brown’s body lies a moldering in the grave.” But where is that grave? It turns out Brown was buried at New Elba, New York, where he had headquartered for several years in an intentional Black community. Brown came to regard himself as something of a savior of Black people in America, and he seems not to have been a racist in any of the usual senses of the word. Brown respected Black people. He broke bread with them, slept in their homes, opened his home to them, listened to them, argued with them, strategized with them, and sometimes suffered alongside them. Many northern abolitionists, like Emerson, were opposed to slavery. Still, they did not regard African Americans as equals, and they preferred not to have much contact with them unless they were white-approved, like Frederick Douglass.

Hero or Terrorist?

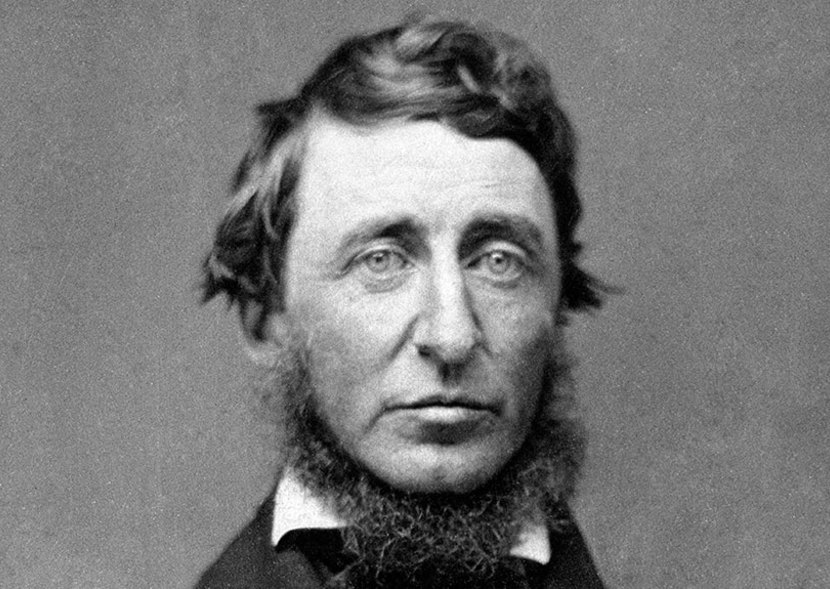

Was John Brown a hero, or was he a terrorist? Where you stand depends on where you sit. In the Concord, Massachusetts, of Emerson, Thoreau, Channing and Alcott, Brown was regarded as a martyr and maybe a saint. (This had not always been the case.) And in Concord, none was a greater apologist for John Brown than Henry David Thoreau. Between Brown’s conviction in Virginia and the public execution, Thoreau gave a lecture in Concord entitled A Plea for John Brown. Thoreau said Brown could not be judged by his peers because he had no peers in America. On the lecture platform, in front of some of the most cultured and well-read people in America, Thoreau said Brown was the most authentic American and the most authentic abolitionist because he walked the walk — all the way to armed struggle — while others were wringing their hands and pretending that the southerners would eventually be persuaded that slavery was a fundamental violation of human rights and moral abomination. Brown knew better. Thoreau drew an unmistakable connection between John Brown and Christ in his lecture.

It was a radical address. Thoreau said some things that would be regarded as blasphemous in almost any American community of the time and in our time. What amazes me — and fills me with admiration — is that the people of Concord sat quietly through the lecture and neither assaulted nor shunned Thoreau thereafter. Some were convinced and converted. Others agreed that Thoreau had a point. Concord, in that magical era, comes as close to American intellectual utopia as we have ever come to in a single community.

Brown liberated 11 slaves in Missouri in 1858 and then led them on an 82-day, thousand-mile march to Canada. Brown led himself and did not delegate. Did not start out and then peel off or, like Mussolini, join the March on Rome for just a minimal but crucial photo-op time.

A cynic of our era might ask of Brown’s actions: “What was in it for him?”

The answer seems to be pure. Brown regarded slavery as a system of organized violence that violated the equal rights of Black men, women, and children. That wrought deep psychological damage on every person, white or Black, that connected with it, including the bankers, insurers, and shipping interests of New England. He believed the slave system could not be broken by political means, not as the existing U.S. Constitution was written and construed. He dreamed that he could liberate America’s slaves, plantation by plantation, region by region, with the least possible killing. Still, he also reckoned that blood was going to have to be shed not just in the border territories but in what he called “Africa” — the slave states of America, beginning with Virginia.

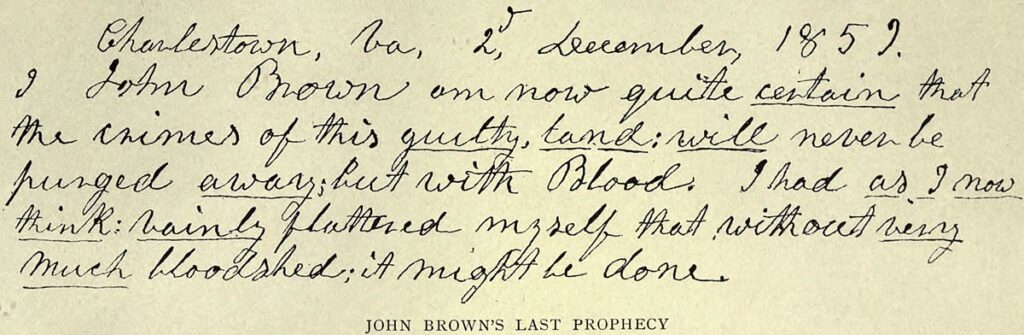

Brown’s last words, written on the day of his execution, were starkly prophetic: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood. I had … vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed, it might be done.”

Brown believed that the Founding Fathers did not intend America to perpetuate slavery beyond their own time and place. He believed the Constitution did not protect the extension of slavery into the territories of the West. Brown was confident that he was reading the intentions of the Constitution more accurately than the “political philosophers” of the South. More than that, he was absolutely certain that slavery was incompatible with American ideals. If slavery were not wrong, he argued, then the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights were just agreeable bits of rhetoric, not fundamental standards for American behavior.

Even those who loved him acknowledged that he was obsessed, that he was a monomaniac, and that he might be mentally unbalanced, at least in some things. One of my favorite pieces of American art is the 1942 mural Tragic Prelude, which has a preferred place in the Kansas state Capitol in Topeka. The John Brown of this massive (31 feet by 11) and amazing work of art is not a pacifist. He is an Old Testament Prophet. He is Moses. He is the Whirlwind to be reaped by those who fattened on the institution of slavery. His long arms are outstretched, a rifle in one hand and an open Bible in the other. His beard is as long as that of Michelangelo’s Moses. He is standing on a pile of pro-slavery corpses, but, standing between soldiers of the Union and the Confederacy, he also looks a little like a hockey referee about to drop the puck at center ice.

He had 20 children in all, the majority of them boys, and about half of the boys wound up joining his guerrilla raids, some very reluctantly. A number of his children were killed in these years, and several of the survivors suffered from severe PTSD. Several had breakdowns, physical and mental, and died young. His long-suffering wife, Mary (who was fully committed to John’s mission), lived 24 years after his hanging.

Although he had prominent (albeit secret) New England backers for his anti-slavery campaigns, Brown initially lost a great deal of support in the northern liberal and abolitionist community in the autumn of 1859 because he had mounted a pointless and futile attack on a federal facility, and killed people in the process. This, they thought at first, was going too far. But once he began to speak at his trial, he changed almost everyone’s mind, even the initially skeptical Ralph Waldo Emerson and the equally skeptical Frederick Douglass. (Thoreau, typically, had been a stalwart throughout). Brown’s brief, straightforward, candid, and unapologetic statements in the courtroom and at his death circulated through the United States like wildfire thanks to the newfangled media platform, the telegraph. Historians say the Raid on Harpers Ferry was the first “breaking news” event in American history. We had just enough telecommunications infrastructure to instantly disseminate news of the trial to every corner of the North. Leslie’s Weekly and Harper’s (and others) sent their finest artists to produce illustrations of the prosecution and the communities of Charles Town and Harpers Ferry in a close to instantaneous way.

Even the openly racist governor of Virginia, Henry A. Wise (1806-1876), who loudly and publicly prejudged Brown’s guilt, came away from an interview with the prisoner acknowledging that he was dignified, candid, unremorseful, quietly forceful, unself-protective, and “game.” For a short time, Governor Wise thought of sending Brown to an asylum rather than executing him. Still, after meeting him in jail, he concluded that Brown was not insane (or had been temporarily insane at the time of the raid), partly because Brown declared that he flatly rejected any insanity defense. He wanted America to know that what he did was absolutely sane.

But what exactly did he have in mind? He wanted to be the American Spartacus, the hero of the Roman slave revolt (73-71 BCE), but to win this time. He wanted to take over the huge store of arms at Harpers Ferry to touch off a widespread slave revolt and, side by side with former slaves, build a mountain sanctuary and fortress where self-freed Blacks would train to continue the struggle in every slaveholding region of the nation until all of America’s slaves had essentially undertaken a nationwide strike, using their numbers to overwhelm those who would use violence to quell their revolt, and then just walk away from the plantations where they had toiled for white masters.

His raid on Harpers Ferry failed miserably. The local Black population did not rise to form the core of Brown’s liberation army, partly because they had not been canvassed clandestinely in the weeks and months before the raid. Still, historians rightly see the raid as the start of the Civil War, 16 months before Fort Sumter.

John Brown had taken the force of violence into the heart of Virginia, and his headquarters maps showed a large number of other strategic sites that he intended to raid once the first stage of the war of liberation (and retribution) had been won.

As much as any single individual, Brown kept Kansas free. That meant the spread of slavery into the Far West was stalled east of the hundredth meridian and probably terminated. Brown said he was not afraid to die for a cause so clear and pure. He kept his composure right up to the moment when the gallows dropped out from under him.

It’s an amazing story, and I have spent considerable time trying to imagine the effect of something like that today. In the next couple of years, I plan to visit John Brown sites in Kansas and New York. My reading has just begun. And I intend to spend an hour gazing at Tragic Prelude in the capitol at Topeka.