Day Three: Wall, South Dakota, National Grasslands and Badlands National Park

On Clay’s third day on the road from Bismarck to Vail, he travels through Wall, South Dakota and visits the U.S. National Grasslands Visitor Center and Badlands National Park.

When you wake up in Wall, South Dakota, you must make a choice. More Wall Drug, or get the heck out of there? I had a breakfast certificate at a downtown restaurant. Still, I didn’t want Annie Oakley shooting up my orange juice or a guy in a Sitting Bull costume on a stool next to me ordering a caramel macchiato with vanilla oat milk. I won’t say that when you have seen one jackalope, you have seen them all. That would be blasphemy. But you’re topped up on the elusive jackalope when you have seen a hundred in a single hour. The only thing I still wanted to do in Wall was go to the Grasslands Visitor Center.

And yet, as I drove around the village of Wall, I happened on what can be called the World’s Largest Jackalope, constructed on a side street by a chainsaw sculptor. Now I’m a lover of the world’s largests, and I have visited as many of them in America as any other person, but this one I found intimidating. I stopped the car to take photographs. A woman was opening the door at the base of the jackalope, which you can enter and ascend to its top, like the Statue of Liberty. She invited me to “come on in.” But I didn’t. If you enter the maw of the World’s Largest Jackalope, how do you know you will ever come out? What goes on in there?

U.S. National Grasslands

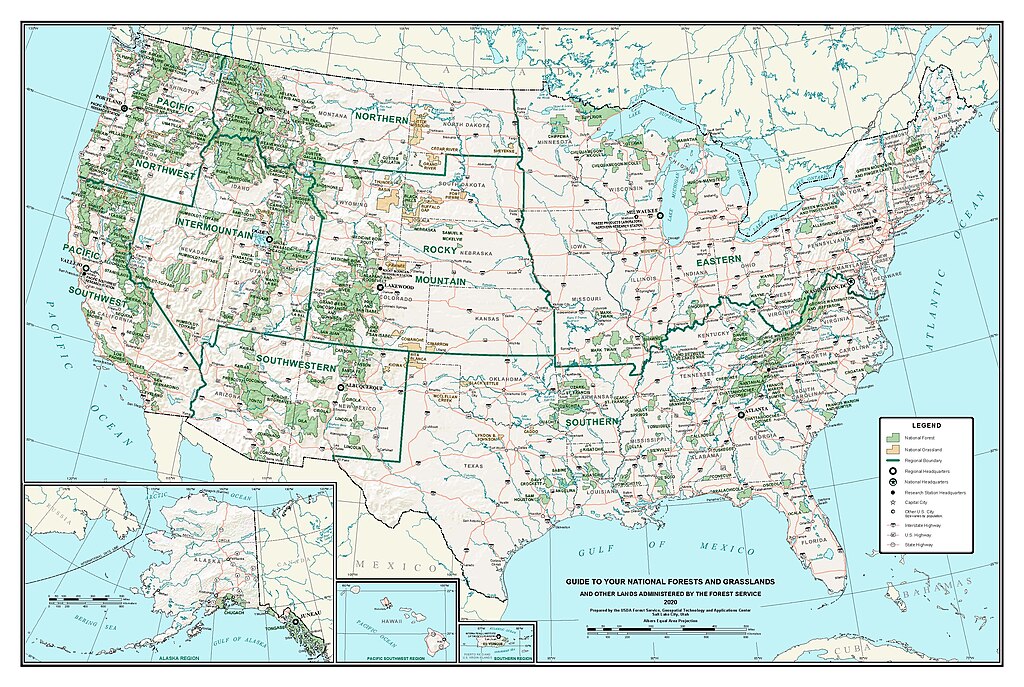

The U.S. National Grasslands are one of the great legacies of the New Deal. Economic collapse and the severest drought in American history impacted the Great Plains more than any other region. FDR stepped in with programs and agencies designed to bring economic and environmental stability to the marginal and sub-marginal lands of the trans-Mississippi West. One result was the Soil Conservation Service (SCS). Another was the Bankhead-Jones Act (1935). The U.S. government bought up bankrupt and eroded farms and ranches and abandoned properties, began restoring them to pasture, and then — this is the most remarkable part of the story — leased those lands back to the farmers and ranchers who had gone bust and dust.

My North Dakota has three National Grasslands units, including the largest one in the system, the 1.2-million-acre Little Missouri National Grasslands. They envelop the three units of Theodore Roosevelt National Park like a conservation buffer. Almost every public acre is leased to a rancher and used for grazing cattle. It’s fenced. It’s not open land the way a National Forest is open.

The only Grasslands Visitor Center for the entire national system is in Wall, South Dakota.

I ran the gauntlet of Wall’s main street to reach the center precisely at 8 a.m. But it was closed. The center had recently suffered extensive water damage. But a FEMA-like trailer parked on the curb served as the temporary visitor’s center. I clunked up the metal ramp and entered. There was the usual high counter with maps pressed under glass and a cheerful ranger in full uniform with brightly painted and pointed fingernails. There were racks of maps. There were some pelts (coyote, fox, etc.) you were invited to fondle. And, of course, even in so small a center, there was the obligatory 18-minute orientation video — a few books for sale, of which I bought two.

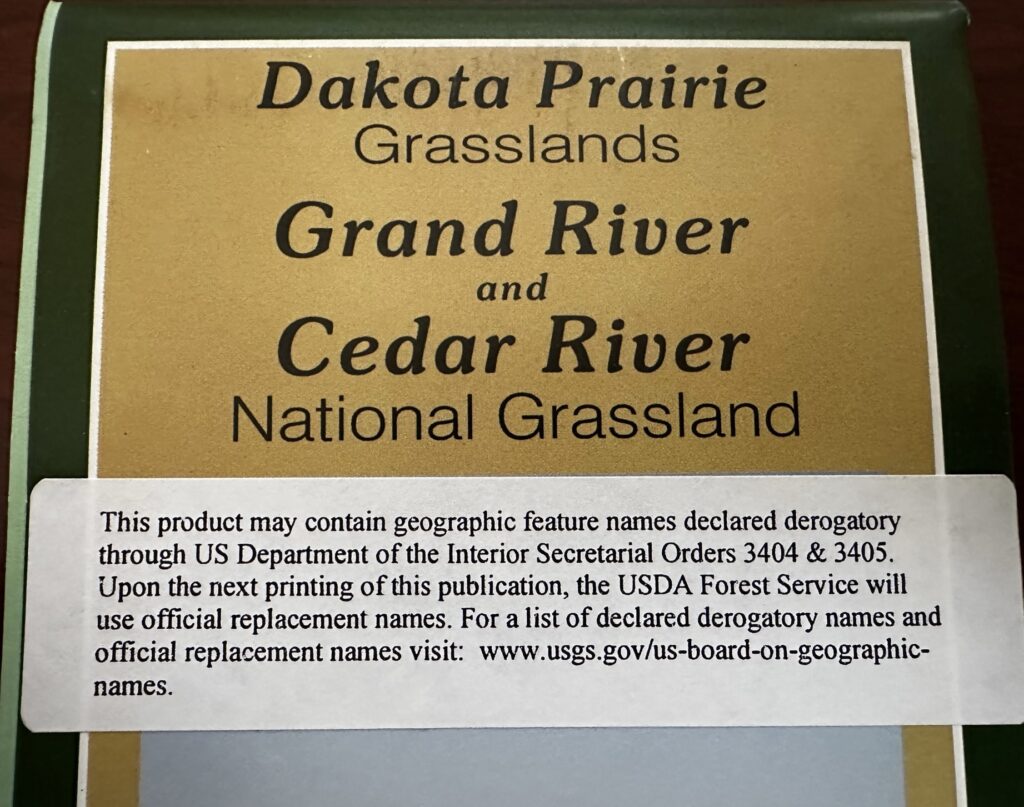

This product may contain geographic feature names declared derogatory through the U.S. Department of the Interior Secretarial Orders 3404 & 3405. … For a list of declared derogatory names and official replacement names visit: https://www.usgs.gov/us-board-on-geographic-names.

The film was about the greatness of the black-footed ferret. These ferrets are cute; I’ll give them that. They are the meerkats of the Great Plains. They are almost always on the brink of extinction. Grasslands experts would like to re-introduce them. The ferrets live with and dine on prairie dogs. This is the kind of federal program that annoys most ranchers. Ranchers are not friendly to prairie dogs, which crop the grass and create a dangerous labyrinth of holes in the ground that horses and cattle can trip in. In a ranch town recently, on that notice board near the restrooms, I saw a handwritten sign that said, “Looking for youngsters to come shoot prairie dogs on my ranch. Call …” Black-footed ferrets are also susceptible to bubonic plague (the one that killed a quarter of Europe in the fourteenth century). But mostly ranchers worry that if they cooperate with the federal grasslands biologists, allowing an endangered species to be introduced on their ranch, their every move will be monitored and regulated. If the ferrets are thriving on the hay flat, they won’t be permitted to cut hay.

And, as you might expect, ranchers have other things to do than to bring new vibrancy to the prairie dog towns on their range. The ranch community that leases federal grass is always bracing itself for the next federal employee who drives up to introduce “an exciting new program” cooked up by someone who has never fixed a fence, lifted a bale, or pulled a calf in the middle of the night. I’m all for the re-introduction of the black-footed ferret. I’d like to see the re-introduction of many species on the federal grasslands, but I try to remember that FDR’s purpose was to restore the range and stabilize the rural economy to keep good people on the land.

I groaned when I saw the new National Grasslands decal has a lovely ferret peaking at the top.

Badlands National Park

I drove south into Badlands National Park. Within a few hundred feet, eight cars were parked, with people crouching on the grass taking photographs of prairie dogs and about a dozen bison. At the gate, I whipped out my Geezer Pass, the NPS Senior Pass that gives you nearly universal access to National Parks, National Monuments, and more. All for $80. Not per annum, but for as long as your heart keeps ticking! It’s the greatest bargain in America.

I drove the rim road on the northern plateau of the badlands to Scenic, population 52, just above the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, home of the Oglala Lakota. At the Badlands National Park Visitors Center at Scenic, I studied a line of black and white portraits of Lakota leaders who survived the Wounded Knee Massacre. That’s a remarkable approach to the massacre — not the 250 who died there on December 29, 1890, but those who survived. I don’t think I have ever once previously thought about the survivors. One of the most persistent themes in Native American commentary, here or at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., is “we’re still here.” All those furious attempts by white people to erase Native American culture or Native Americans per se (“Kill the Indian, Save the Man,” said Richard Platt, the founder of the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania), failed. The resilience of Native Americans is impressive, given the odds and the land lust of the white invaders. Resilience is, in my opinion, the single most important characteristic of Native Americans.

Pondering What Is Sacred

When I am alone exploring and wandering on backroads, I stop whenever I want to take photographs. Every time I got out of the car into that June morning, the nearest meadowlark sang its glorious song. I regard the meadowlark song as the quintessential sound of the Great Plains. And these were smug National Park meadowlarks who knew their habitat was forever secure. They sang like chanticleers in the glory of the morning. It was thrilling.

And then I noticed the sky. A huge, isolated anvil of a cumulous cloud was building from slightly north or west, backed by the slate gray of a possible thunderstorm later in the day. It was one of the largest clouds I have ever seen, alone in the sky like a cosmic battleship. And pure white. Building. Log.

We spend most of our lives inside, in temperature-controlled buildings with fluorescent lights and ceiling panels. How much time do we spend gazing at the sky? Not nearly enough. Now I was in the heart of the Lakota (Sioux) homeland, and the sky was alive. I use each of these words, homeland and alive, deliberately.

First, homeland. From a white man’s jurisdictional point of view, I was not on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Still, from a Lakota point of view, I was a visitor to their sovereign national homeland. The Lakota have never accepted the abrogation of the Great Sioux Treaty of 1868, which guaranteed them all western South Dakota forever. They are playing the long game. They believe the U.S. courts will increasingly support their just claims. They intend to press their claims against the National Parks, many of which, including this one, were carved out of Native homelands. This includes the possibility of Native Americans co-managing parts of some National Parks. They have some residual hope that a more enlightened era of white government will do justice in Indian Country. Meanwhile, they are “buying back” parcels of their homelands lost through the Dawes Severalty Act (1887).

Native Americans are playing the long game. And meanwhile, every Native American nation sends its most promising young people off to colleges and universities to get degrees in law, medicine, nursing, politics, anthropology, and business. Already the first great wave of those young people, Lakota and Cheyenne, Arapahoe, and others are in the arena, challenging the white world to make amends and embrace justice.

Now, alive. I have no adequate language to describe how watching that colossal cloud inch toward me felt. I felt deep envy for cultures that live under the open sky. You cannot be an insurance adjuster in Rapid City and know the sky the way it deserves to be known unless you go way out of your way. You get some of that sky power if you are a rancher. But if you were a Lakota or Mandan living during the golden age of the horse (1725-1870), you lived between the earth and sky, which had meaning far beyond the meteorological.

The sky was alive that morning in western South Dakota. To regard the sky as a series of phenomena that can be described with a spectrometer or a nomenclature — Cirrus, Altocumulous, is to miss the point, fail to see and be open to the spiritual.

I thank God that I live on the Great Plains of America. They are, to me, and perhaps to everyone, difficult at times. But the plains and the culture they support are deeply fascinating, occasionally in a cringey way. But there is so much good in the less settled West. You can try to leave it behind in the rearview mirror, but you can never get it out of your soul. The plains are where you go to get swallowed up by grass and sky.

The cloud above me continued to grow with each passing minute. I would have liked to set up a camping chair on a grassy hill and spend the day just watching it, waiting for the first hint of heat lightning. I learned again for the umpteenth time that you must get yourself out there to really know it. You cannot pretend to love it from your sanctuary of urban life. It’s out where the grass grows. It’s where there are distant ridges. It’s where you suddenly feel alone in a universe of grass, a touch of the savannah that both thrills and terrifies us all at once.

The massive cloud in the northwest sky was slowly darkening. I stood out in front of my car for a long time, trying to make sense of it. The word rattling around in my brain was “sacred,” but that is a big word that should not be tossed about lightly, especially by someone from a largely despiritualized society.

In June, Clay drove from his home in Bismarck, North Dakota to Vail, Colorado. A focus of Clay’s two-week road trip was exploring little-remembered sites of tragic encounters between Native Americans and an expanding, westward-moving white population of the 1860-1880s. Clay’s stops included a battle site at Whitestone Hill in North Dakota in 1863, as well as the spot in Nebraska where Crazy Horse was killed in 1877, and Colorado sites commemorating the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864. Along the way, Clay also visited the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site, the U.S. National Grasslands, and a forgotten mountainside in western Colorado, where the federal government detonated a nuclear bomb in 1969 in an experiment to explore the peaceful use of atomic weapons. And — as in all good journeys — unexpected and unrelated roadside distractions provided plenty of ways to think about America.