During a long life of hard reading, Henry David Thoreau’s Walden is the book that helps me understand what it is to be human.

I’m reading Thoreau’s Walden. It’s my Bible. I love certain books in the Judeo-Christian Bible: Genesis, Job, Ecclesiastes, Proverbs, the Gospels, Acts (especially), several of Paul’s letters, and the insane and fabulous Book of Revelation. But the Bible speaks to me now solely as a core text of the humanities. It does not shape my life. Well, forgive others, turn the other cheek; the rich will have a harder time getting into heaven, the golden rule — those all work for me. But the Bible as a whole is not a book I turn to when I need guidance in life. As Thomas Jefferson said, any child of five can understand the basic ethical message (and he was not interested in theology or metaphysics).

I’ve dabbled with some Eastern texts, but they impress me chiefly because they are so not the West. I don’t find much solace there either, and I am suspicious of those who say they prefer Eastern texts. This seems to me not much more than a way of despising our own tradition. I’m trying to think of one essential human insight that the Upanishads provide that cannot be found in the Bible. This is a shallow view, but it is the view I hold.

When I want to wrestle with life’s big questions, I do not turn to the Bible. I find the Quran nearly impenetrable (as I do most of the Old Testament). When I need to pray, I go to some isolated place in the badlands of the Dakotas or Montana and settle on a ridge or in the pines with a big viewshed. I pray both internally and out loud. Just who or what I pray to is not entirely clear to me. I don’t think the universe is taking my calls. From my long study of St. Augustine, I believe the only legitimate prayer is: Thy will be done. That doesn’t win the war, the mate, the ball game, or the battle with cancer. But while on that ridge, I give myself the time to wrestle with whatever question is foremost. Just put me alone for three hours on a temperate day in some left-alone corner of the American West. I’m going to think clearly with the right perspective (i.e., if I died on that ridge, it would take civilization weeks, maybe months, maybe years, to find me, so how urgent can my concerns be)?

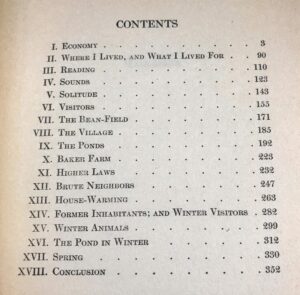

No Chapter in Walden Does Not Speak to Me

During a long life of hard reading, I have found that Henry David Thoreau’s Walden is the book that helps me understand what it is to be a human mammal living in a very advanced civilization, cut off from Nature in breathtaking ways. The questions Thoreau raises — what is the “cost” of the way we live, and would it be possible to live a more poetic, integrated, and soulful life if we reduced our material addictions? — are the questions that help me think about life, my life, American life.

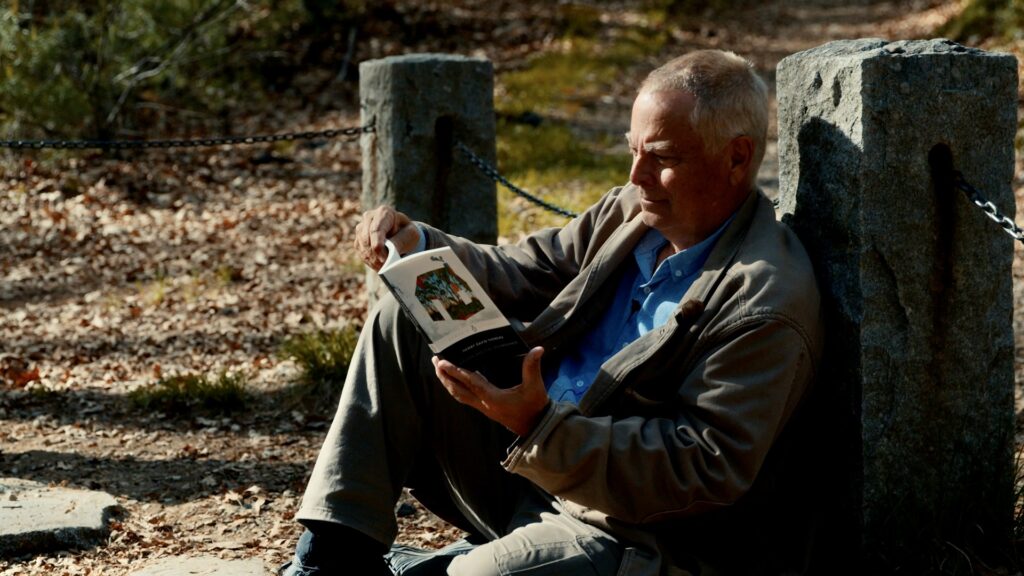

No chapter in Walden does not speak to me. I’m reading it now for the umpteenth time, and it still delivers new provocations, new insights, and new encouragements to me. I’ve read it in some fascinating landscapes — most intensely 20 years ago on a long hike of 173 miles over 17 days along the path of the Little Missouri River in Wyoming, Montana, South Dakota, and my own North Dakota. The first two chapters and the last one speak to me most often and most successfully. People whine about the long first chapter, called “Economy,” but you cannot understand what Thoreau was about, what he was trying to figure out, and the experiment he was undertaking unless you give the first chapter plenty of time. Thoreau said you have to train like an athlete to read the greatest books. I see my work as a public humanities scholar (if we are talking about Thoreau) as helping the bewildered and the disaffected come to terms with “Economy.”

The greatest passage in all of Thoreau — and that’s saying something given that he wrote more than 2 million words — comes in “Where I Lived and What I Lived For,” beginning, “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately.” You could spend a lifetime trying to figure out what it means to live deliberately. I’ve memorized the passage long since. I recite it whenever I get the chance, alone or otherwise, and I try to figure out what it would be like to live deliberately — I am a very long way from it — and whether I can learn to do so, and if so, by what discipline?

And then there is the gnomic and magnificent last chapter of Walden, “Conclusion,” in which we learn about the worm that ate its way out of the kitchen table after 60 years, and we are charged to “advance confidently in the direction of our dreams.” And, of course, the incredible last sentence: “The sun is but a morning star.” Oh, bring mid-day and evening (but not yet).

How to Consult Walden

In the Middle Ages, when Christianity had destroyed or repurposed almost the entire classical inheritance, with thousands of pagan temples looted, crushed, or transformed into Christian churches, Virgil’s great epic The Aeneid survived the censors because it could be seen somehow as an allegory for the Christian life, a kind of early and more sophisticated Pilgrim’s Progress. To repeat: we have The Aeneid, one of the world’s greatest books, almost solely because the Christian intellectuals found a way to square it with their doctrine. This took some pretty serious legerdemain, but remember that the same believers found a way to pretend that the pagan erotic Song of Solomon was really about Christ and his “spouse.”

A tradition was born in the late classical period of consulting the pages of The Aeneid in the way we consult the I-Ching or the Enneagram. It was called sortes Vergilianae. The first historical reference to the practice was pagan, in Aelius Spartianus’ Life of Hadrian (ruled 117-138 CE). The aspiring Hadrian, wanting to know what Emperor Trajan thought of him, opened The Aeneid at random and found — conveniently enough — the verse that reads, “the Roman king whose laws shall establish Rome anew.” And it turned out that Trajan eventually adopted Hadrian as his son and Hadrian became his successor and one of the greatest emperors in Roman history.

The most famous consultation of the sortes Vergilianae happened in 1642-1643 at Oxford. The beleaguered King Charles I was visiting the great loyalist university. His host urged him to consult Virgil in the prophetic way. The passage Charles opened to was not as pleasing as the one Hadrian chanced (?) upon. This time the sortes delivered, “May he be harried in war by audacious tribes, and exiled from his own land.” Seven years later, King Charles I was beheaded on a scaffold outside of the Banqueting House at Westminster.

Once a year or so, I consult Henry Thoreau in the manner of sortes Vergilianae. And though Walden does not tell me to “buy low and sell high,” or encourage me to seek a future in “plastics,” like The Graduate, it always delivers something worthy of my sustained meditation.

Look. I’ll try it right now.

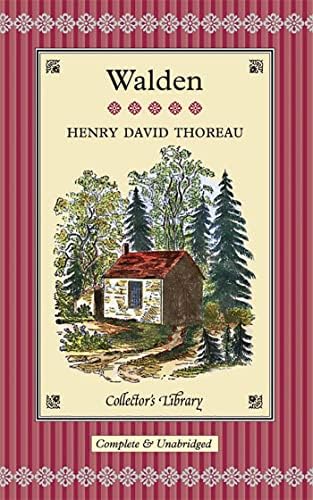

Just now, I went down into my main library to get the edition of Walden that matters to me most. It’s a Collector’s Library hardbound edition with a red cover and afterword by Sam Gilpin. I love it for two related reasons. It is compact and with a hard cover relatively durable; and I took it on my last multi-week hike on the Little Missouri River. (There are some lovely signs of the toll the journey took on the book and of course me). It measures 6 x 3.5 inches. I’d call it a duodecimo, but technically it is known as a sextodecimo. It weighs only a few ounces. We’ve all seen teeny books (a novelty) or the single grain of rice on which the Sermon on the Mount is incised. Novelties. When I see people purchasing a tiny box of the complete works of Shakespeare (884,647 words in a box the size of a wristwatch case), I want to say, “You know you are never going to be able to read Shakespeare this way.” Still, I don’t because I don’t offer up my opinions to people who haven’t asked for them.

This copy (one of 20 in my library) is the smallest size that is still readable.

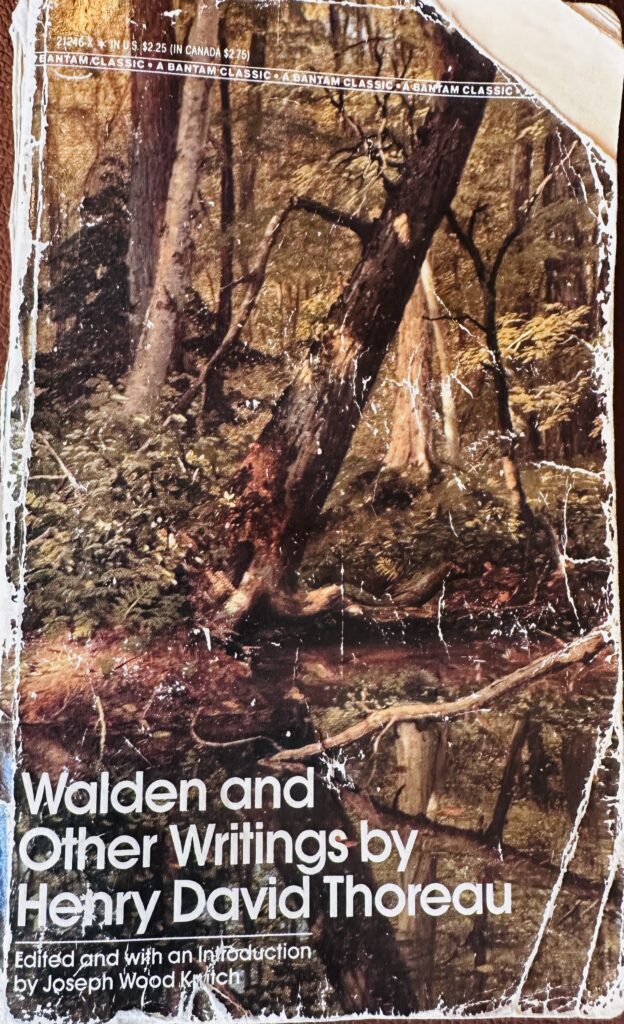

I have one other sacred copy of Walden in the library. It’s a Signet Classic paperback edition, with (on the cover) someone sitting under a tree by a pond. The cover survived a serious tear 20 years ago, and I fixed it, MacGyver-like, with several pieces of black electrical tape. There went my career as a conservator. I took that copy on my previous and longer hike on the Little Missouri River, beginning in the shadow of Devils Tower. Years later, I made a colossal mistake. I was dating a woman in Reno — whip-smart, badly read — who borrowed that copy of Walden for a project we were working on together. When she returned it, I discovered that she had highlighted scores of passages … with a bold pink highlighter! There were other reasons to end the relationship, but this alone would have done it. I get to be a carnal lover of my books — marginalia, underlinings, dog ears, coffee and peeled orange stains, endnotes — but nobody else gets to have their way with my books. Especially sacred books! The pink highlights are my fault. I should have known better than ever to lend any important book to anyone. I’d rather order them a trade edition, delivered to their front door three days later at most than put a book I could not afford to lose or see damaged into the hands of even my most trusted friends. And really, who can you trust about a borrowed book?

Ok. That’s the back story, told while this fabulous copy of Walden prepared to be the Sybil, the Oracles at Delphi and Dodona, the waters of Lourdes, or the Medicine Rock of the Mandan and Lakota. I picked up the book and held it lovingly in my hands. Then I fanned the (faux) gilt pages nine times and, on the 10th, opened the book where it seemed to want to be opened: the first two pages of chapter five, “Solitude.” Weird, I just read that chapter in another copy — the annotated edition prepared by Walter Harding.

Ok. Let’s see what the sortes Thoreauvianae have to say today.

Henry is walking by the pond as the afternoon’s wind dies. The chapter begins with one of my favorite passages in Thoreau: “This is a delicious evening, when the whole body is one sense, and imbibes delight through every pore. I go and come with a strange liberty in nature, a part of herself.” There’s a paradox here, of course. When he writes, “This is a delicious evening,” it no longer is. He’s not carrying around a notebook and stopping to get his thoughts down. But we get the trope. I love his gendering of nature, and I even more admire his understanding that he does not stand apart from nature — Francis Bacon style — but acknowledges that he is “a part of herself.” I love it when he says he feels “a strange liberty in nature.” Magnificent.

So far, I appreciate the pages fate opened for me, but I have not yet applied the passage to myself. Let me get one more from this two-page spread on the table first. Thoreau says his nook in the woods (1.5 miles from Concord) is “as solitary … as on the prairies … I have, as it were, my own sun and moon and stars, and a little world all to myself.” Wherever you stand on earth, you are at the center of the universe because it is endless in every direction forever. And wherever you view the stars you have a unique view (unique among 8 billion other humans) because of parallax, however infinitesimal the difference.

First, let me make my main point. As I have just shown, open Walden to any page, and you will find enough beauty, wisdom, insight, provocation, challenge, confession, perspective, or aspiration to keep you musing for the rest of the day, whether you are at the confluence of the Green and Colorado rivers, or your kitchen table (as I am at this moment, but thinking about the other one). Walden always delivers. As the guy says in the Men’s Warehouse ads, “I guarantee it.”

Great books deliver their greatness every time, often in ways you hadn’t noticed before. It’s bizarre (a little self-disappointing) and wonderful.

The Application: Quid Ad Nos (What Is That to Me)?

I’ve been wrestling with the question of solitude lately. I am alone most of the time, more probably than anyone I know. I do live on the prairies — well, more accurately the Great Plains, just 200 miles west of the prairies. I don’t prize solitude as militantly as Thoreau. He wanted to have strict protocols for friendship (much less love). 1. Come around only once every few days so we will have some new things to talk about. 2. Sit far enough away so our thoughts can do some sinewy flight time from your mouth to my ears and the reverse. In fact, as the conversation deepens, plan to scoot your chair back until each of us is up against a wall. 3. Don’t expect to eat, though you may. 4. Don’t bring any dead-weight people.

I need a huge quantity of solitude, though it might be less pretentious to say “alone time,” but I like and love the ones I like and love, most of them not in my zip code or even my home state, and I am eager to see them when we can arrange our schedules — which admittedly is not often. I like solitude when I want solitude, but I am not content to be alone for long periods without seeing anyone else. I own a splendid Thoreauvian (10 x 15 foot) cabin at Cooke City, Montana, just two miles from the northeast entrance of Yellowstone National Park. It’s an Airbnb now, so have at it if you are looking for a minimalist but comfortable retreat near the first of America’s National Parks and still the most iconic. I want to go spend a month there writing the Great American something, or maybe just finishing one of the more journeymen projects I have committed myself to. Sounds perfect. But how long would it be ok for me to be alone with the English language among the trees at the side of the mountain in the heart of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem? I remember a famous edition of the Dick Van Dyke Show, where he rents a remote cabin so he can finish his languishing novel. Unfortunately, on day two, he finds a paddle ball (ball, paddle, strong elastic band) in a drawer. When he goes home a week later, he has not written a single page of the novel but has become a paddle ball grand master.

I love Thoreau. He had a delicious evening, and he wrote deliciously about it. That he used the word “delicious” delights me. Here’s his genius. He uses the English language in masterful ways, in unusual ways, and often deeply poetic ways, and yet does not lose the tensile strength of his argument against America.

So that’s how the sortes oracle works. Walden did not tell me how to live today. It did not today say downsize, or sell all you have and give it to the poor, or ’tis sharper than a serpent’s tooth to have a thankless child. But it resonated with things I have been thinking about since early December, things I have in some sense been thinking about since I embarked alone in my 23-foot Airstream on April 27, 2024. Earlier today, I wrote about solitude in a letter to a friend. I was trying to figure out what solitude meant to Thoreau and what it meant to Edward Abbey and if their errands into the wilderness were alike or not — or what? Abbey needed more human contact (especially with fetching women) than Thoreau (who almost certainly never had sex), but we need to remember that Thoreau walked to town every couple of days during his sojourn at Walden Pond. Yes, the laundry — get over it already. The sortes contributed to my thinking, my musing, my perplexities. And it was just lovely to read a second time in a single day.

I’ve got miles to go before I sleep. I’m about to read the chapter on “The Bean Field” for the umpteenth time. I don’t remember it as one of my favorites, but I can promise that I will take several pages of notes, underline a dozen passages, copy several into texts to friends, and use Google Images to look up a bunch of things. I’ll give this attention to only a handful of books. It’s slow going. But it’s marvelous.

Here’s what I took from “The Bean Field.” A: Thoreau was not really interested in eating the beans. He’s a little perplexed by that. He traded the 12 bushels of beans for rice. B: Thoreau wrestles with the problem of agriculture, that he has displaced natural plants to impose a kind of monoculture on his 2 ½ acres of garden. The paradox has special pointedness considering that he was not growing the beans to eat. C: Thoreau employs some delightful mock epic tropes to talk about his war with the weeds, trying to crowd out his beans. D: His war on weeds reminds me of Michael Pollan’s argument, in one of his books, that the gardener suddenly becomes an angry tyrant who seeks to eliminate, as ruthlessly as possible, other beings competing for the resource. The only thing I looked up on Google was “Pythagoras and beans.” Apparently, Pythagoras felt that the shape of the bean seemed too close to the shape of a human fetus to whet his appetite. He regarded humans and beans as “related.”

I cannot take you with me, though I would like to, so I leave you to pick up Walden or whatever book most speaks to your mind, heart, spirit, and soul and do the sortes with it. I, meanwhile, move on to the chapter entitled “The Village.”