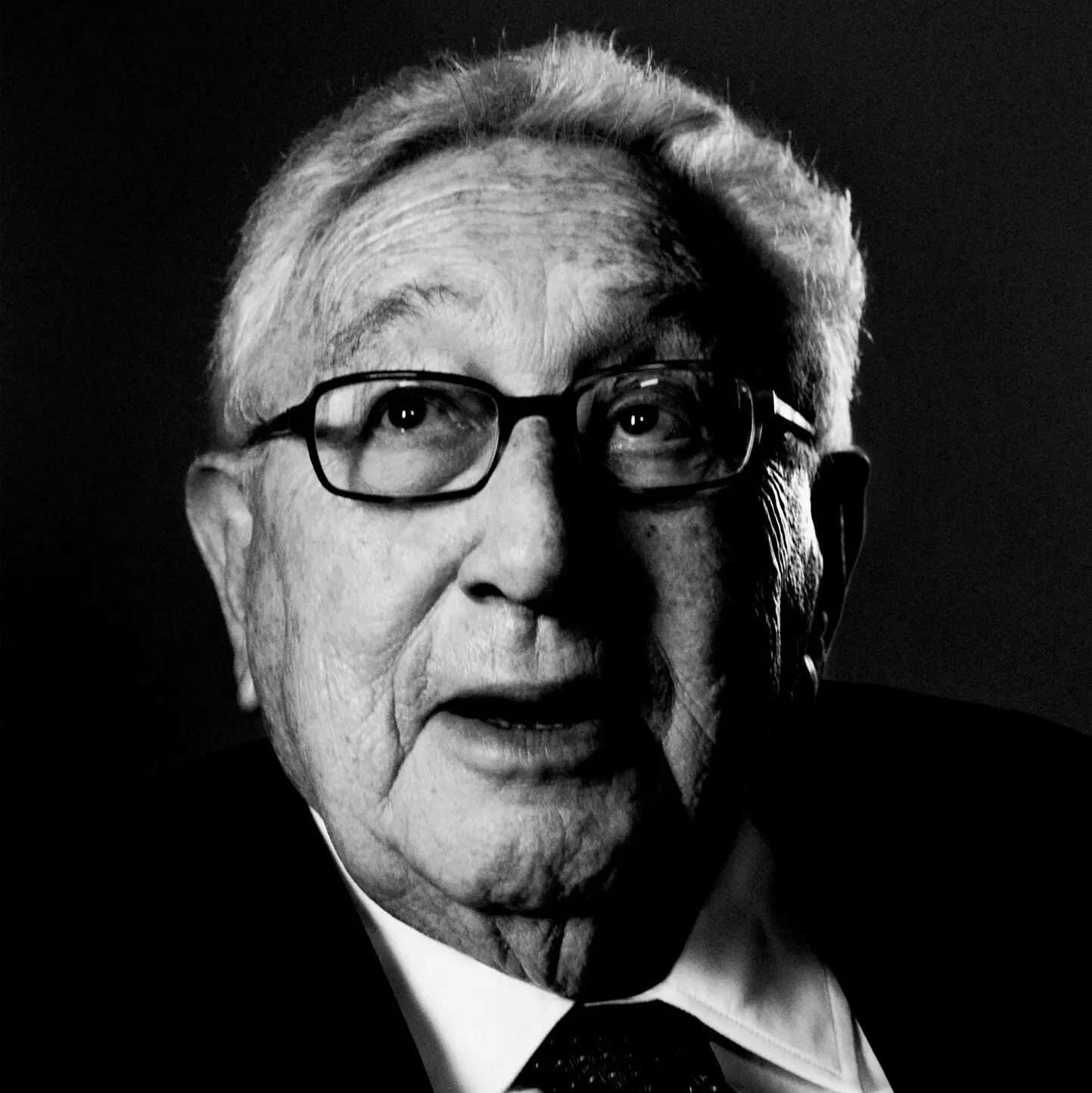

Adviser to half a dozen presidents, especially Nixon, Kissinger was the only individual ever to serve as secretary of state (1973-77) and national security adviser (1969-75) at the same time.

Henry Kissinger was a colossus.

He was a strategic genius and probably also a war criminal. In 1973 he won the Nobel Peace Prize together with North Vietnamese diplomat Le Duc Tho for negotiating an end to the War in Vietnam. Kissinger did not attend the award ceremony, citing scheduling conflicts. Le Duc Tho declined to accept the award. Two Nobel Prize committee members resigned to protest the selection of Kissinger. Even then, Kissinger’s complicity in the death of millions was well known.

Just two days after Kissinger’s death, George Packer wrote (for the Atlantic), “Henry Kissinger spent half a century pursuing and using power, and a second half century trying to shape history’s judgment of the first. His longevity, and the frantic activity that ceased only when he stopped breathing, felt like an interminable refusal to disappear until he’d ensured that posthumous admiration would outweigh revulsion.”

Kissinger was strangely indifferent to the human suffering he caused or endorsed in pursuit of what he regarded as American ideals.

President Gerald Ford gave Kissinger the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977. In his remarks, Ford said Kissinger “wielded America’s great power with wisdom and compassion in the service of peace.”

Wait. Compassion? Kissinger masterminded America’s illegal five-year bombing of Cambodia and Laos, which killed hundreds of thousands of civilians. Then he lied about it to Congress. Well aware that the bombing raids were killing and maiming innocent villagers who had absolutely nothing to do with the War in Vietnam, Kissinger instructed the American military to bomb “anything that flies or moves” in Cambodia and Laos.

Kissinger encouraged the 1973 coup in Chile that overthrew a democratically elected socialist government, and he supported the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, whose subsequent reign of terror had 3,000 dissidents killed, and as many as 40,000 tortured. Kissinger said, “No matter how unpleasant they act, the [Pinochet] government is better than Allende was.” And he said, “The issues are much too important for the Chilean voters to be left to decide for themselves.”

When Bangladesh was born out of East Pakistan in 1971, Kissinger arranged arms shipments to West Pakistan (now Pakistan) to rain terror on the Bengalis. He did this partly because Pakistan was an American client state that he felt we needed to support in that troubled region of the world; partly because he wanted to support Yahya Khan, the commander in chief of the Pakistan army who had helped facilitate Kissinger’s secret missions to China on behalf of Nixon. The birth of Bangladesh was a bloodbath. More than a million and a half people were killed in one of the most savage wars of the century, and more than 200,000 women raped. “Why,” Kissinger asked, “should we give a damn about Bangladesh?”

Kissinger also supported genocidal actions in East Timor. He supported the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, which resulted in another horrific campaign of ethnic cleansing.

With the news that Dr. Kissinger had died at the age of 100, Gary Bass, writing in the Atlantic, asked, “How many of his eulogists will grapple with his full record in Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Bangladesh, Chile, Argentina, East Timor, Cyprus, and elsewhere?”

Even if Kissinger’s actions can be defended as necessary responses in a dangerous world, what then of the 1949 Geneva Conventions, protecting non-combatants and outlawing some forms of state violence, ratified by all members of the United Nations? If these standards can be jettisoned in the name of expedience, even by “the leader of the free world,” what then is their value? Are these no more than expressions of wishful thinking? Ideals and yet optional? The Geneva Conventions and the human rights standards of the United Nations forbade the bulk of Kissinger’s actions on the global stage.

Former national security adviser Ben Rhodes has written, “Henry Kissinger … exemplified the gap between the story that America, the superpower, tells and the way that we can act in the world. At turns opportunistic and reactive, his was a foreign policy enamored with the exercise of power and drained of concern for the human beings left in its wake.”

At no time in his long life was Kissinger called to account. At no point was he required to answer the hard questions. He was so prickly, righteous, thin-skinned, and abrasive even under the most tepid criticism that it soon became a tacit disqualification for any access to him. There were countries he dared not visit lest he be arrested for what those nations regarded as war crimes. He made it a condition of his public appearances and his encounters with the press that the hard questions were off-limits.

But wait, if he was permitted to order the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people, from elected heads of state to villagers minding their own business in far corners of the world, surely he should have been required to justify his actions — at least in the court of public opinion. Why should he not have been required to face his critics in the United States and beyond? Do we really believe that because he was a charismatic man of great intellectual depth and acuity he should be allowed to operate beyond criticism, particularly when his actions seem to be fundamentally at odds with America’s publicly declared ideals? Surely the price of holding so much power and being permitted almost unilaterally to unleash so much state violence across the globe should be some level of accountability.

I’m not suggesting with his most ardent critics — the late Christopher Hitchens chief among them — that he should have been tried in the world court, but surely neither he nor any other individual should be above accountability of some sort.

Behind closed doors (but while Nixon’s White House tape recorder was rolling) Kissinger called Indira Gandhi a “bitch” and dismissed the hundreds of millions of subcontinent Indians as “a scavenging people,” a nation of flatterers and suck-ups. He told Nixon “The Pakistanis are fine people, but they are primitive in their mental structure.” In a taped conversation with Nixon in 1973 Kissinger said, “The emigration of Jews from the Soviet Union is not an objective of American foreign policy. And if they put Jews into gas chambers in the Soviet Union, it is not an American concern. Maybe a humanitarian concern.” When transcripts of this private conversation were made public, all Kissinger could do was say his remarks were taken out of context. Needless to say, he did everything in his power to prevent the White House tapes in which he spoke such words from being made public. Only protracted legal efforts by journalists and historians have made most, but not all, of Kissinger’s Oval Office remarks public. If this was his attitude toward the non-European, non-Western peoples of the world, it is hardly a surprise that he could order the carpet bombing of their villages without the slightest expression of concern.

He lied to the American people. He lied to Congress.

After the David Frost interviews in 1977, the American people decidedly rejected Nixon’s view that “when the president does it, that means that it is not illegal.” Surely we don’t believe that because the United States is, on the whole, a force for good in the world that if America does some horrendous thing it must be ok.

In recent years he was occasionally consulted on the big international questions. By now he was bent over and fragile, speaking very slowly as if he were using up the last of his vocalizations in real time, but though his body was shrunken his head was still huge and everyone listened to him as if he were the priestess at Delphi or the Cumaean Sibyl. How much of this was self-fashioning and how much was wisdom is hard to determine. When Kissinger spoke in his stooped and hesitant late-life manner, everyone stopped to listen — except those out in the streets demanding that he be turned over to the international courts of justice.

He was America’s most prominent exponent of realpolitik, the idea that nations should do what is in their interest, without much handwringing about morality or Wilsonian idealism. While this is undoubtedly the way things tend to work, realpolitik is not particularly popular in a nation that prides itself on its (self-constructed) reputation for high-mindedness and selfless idealism. America prefers to wage its wars “to make the world safe for democracy,” or to plant the seeds of democracy and self-determination in the Middle East. Kissinger’s unvarnished appeal to selfish pragmatism in America’s foreign policy had its own slightly shocking magnetism. It was a little sexy. He made us feel that he was granting us a glimpse of the way the world really works, behind the public relations rhetoric. Kissinger famously said, “America has no permanent friends or enemies, only interests.”

This is one of those times when we wish Christopher Hitchens was still alive. His loathing of Kissinger knew no bounds. He wrote a book about it: The Trial of Henry Kissinger (2002).

Kissinger symbolizes the pornography of power. In 1968, he was negotiating a Vietnam peace treaty in Paris for President Johnson. He did a deal with the Republicans to sabotage the peace negotiations to help secure Richard Nixon’s election to the president. In return, the world’s self-styled “greatest peacemaker” would be promoted under the new administration. Kissinger’s venality extended the war by four years and cost the lives of millions of Vietnamese, Cambodians and Laotians — not to mention many thousands of US servicemen.

And yet….

Henry Kissinger’s biography is impressive and inspiring. A Jew, born Heinz Alfred Kissinger in Germany in 1923, he came (at age 15) with his family to the United States in 1938 to escape Nazi tyranny. He was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1943. He served in Germany as an intelligence officer. He earned a Bronze Star for helping to hunt down members of the Gestapo. He took his degrees at Harvard. He first became well known in the United States after he advised the Eisenhower administration that “limited nuclear war” might be necessary to protect the West from Soviet domination. He wrote an influential book, Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy (1957).

Urbane. Cosmopolitan. Globe-trotting. Frequently self-effacing, as long as it was on his own terms. Profoundly articulate, rational, and learned. The ultimate insider. The darling of the Georgetown crowd. A master in the geopolitical arena. At times mesmerizing. The center of attention in any room, including when presidents were beside him. And one of the most powerful men of the post-war world.

He could be witty and charming. “No one will ever win the battle of the sexes; there’s too much fraternizing with the enemy,” he said. And he said, “The nice thing about being a celebrity is that, if you bore people, they think it’s their fault.” And, “The illegal we do immediately. The unconstitutional takes a little longer.” (Are you listening, America?)

He was famous for being a ladies’ man. When he was asked how he managed to have a string of young, beautiful women on his arm at public events, he famously said power is the ultimate aphrodisiac. But it must have been more than that. With his thick German accent, thick glasses, and his breathtaking erudition, and the sense he exuded of having access to the deepest levers of global power, he attracted the attention of a wide variety of women, in and out of government, in Hollywood, New York, and Georgetown. The only common ground was that they must be beautiful women.

Most of the other architects of America’s debacle in Vietnam later acknowledged their strategic miscalculations — Robert McNamara, Melvin Laird, Dean Rusk, McGeorge Bundy. Kissinger never did. His usual answer was that he did the best one could do under the circumstances; and there may have been mistakes; but he had nothing to apologize for. The closest he ever came to an apology was in 2002 in London, where protestors demonstrated against his presence at a business convention. He told his audience, “No one can say that he served in an administration that did not make mistakes. The decisions made in high office are usually 51-49 decisions so it is quite possible that mistakes were made.”

That’s the Nixon administration’s passive-voice mantra: mistakes were made.

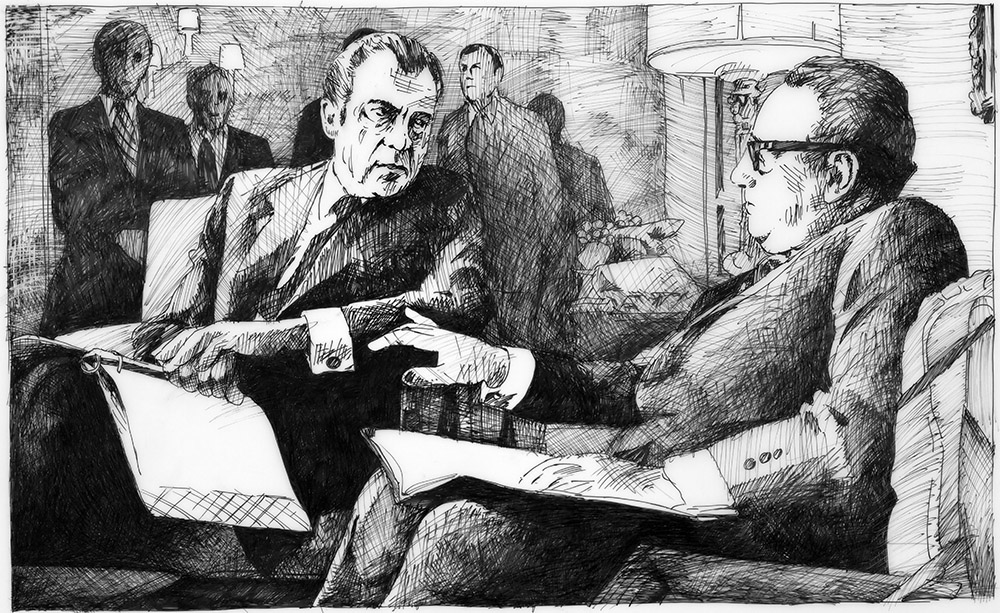

Kissinger was paranoid. He had members of his own staff wiretapped, and members of the press, and dissidents. His obsession with stopping government leaks that were — in his mind — undermining American foreign policy, helped to engender all that we embrace with the word Watergate. He was caught in a trap of his own making. He wanted to maintain the respect of the liberal establishment (Harvard, Yale, Columbia, the Brookings Institute), but his actions were usually at odds with that establishment, but he was so ambitious that he found it possible to insinuate himself into the inner circle of a man of even greater paranoia, Richard Milhouse Nixon. He said he did not like Nixon. He said he regarded Nixon as an intellectual lightweight. He said he didn’t trust Nixon. And yet he volunteered to do the wet work for the administration.

Kissinger and Nixon worked themselves into a dark co-dependency, each one egging the other on to more and more desperate measures. In the end, in the summer of 1974, when Nixon was broken by his crimes and saying privately that he just wanted to die, he convinced Kissinger to kneel with him one night in the Lincoln Bedroom of the White House — the California Quaker and the non-practicing Jew — and pray.

It’s not all bad, of course. He did all the globetrotting that enabled President Nixon to visit the People’s Republic of China in 1972 — an international breakthrough that had been regarded as essentially unthinkable. He performed masterfully in bringing about an end to the Yom Kippur War (fall 1973). He helped lower the temperature with the USSR. He got us out of Vietnam — ignominiously, but he fulfilled President Nixon’s accurate recognition that the American people wanted out, with or without honor.

Kissinger was notoriously thin-skinned and adverse to even the hint of criticism. He was always threatening to resign and though everyone, including his presidents, knew he was merely posturing, they had to go through the charade of caressing his gigantic ego and telling him he was the indispensable man.

Historian Rick Perlstein has written, “He was a prima donna. He didn’t like having a boss. He was famous for volcanic tantrums when Rockefeller’s speechwriters fiddled with his prose: ‘When Nelson buys a Picasso, he doesn’t hire four housepainters to improve it!’”

Being Kissinger was not easy, of course, in spite of the adulation and the power and the women. It was endless and exhausting work, with perennial jet lag, great frustrations, and terrible setbacks. Because we are a “democracy,” with at the time a severely scrutinizing Congress, and because the American people insist upon being portrayed as the good guys in a dark and dangerous world, Kissinger and the presidents he served had to portray their ruthless foreign policy engagements, at least publicly, in a fairy tale language that denied the hard-headedness of our actual role in the world.

Nixon and Kissinger talked endlessly about how to get America out of Vietnam, preferably in some way that would allow the president to declare we had achieved “peace with honor.” But they both knew — and Kissinger more than Nixon — that the war could not be won. In a now-famous 1972 conversation Kissinger finally said, “We’ve got to find some formula that holds the thing together [for] a year or two, after which — after a year, Mr. President, Vietnam will be a backwater. If we settle it, say, this October, by January ’74 no one will give a damn.” In other words, it was worth prolonging the unwinnable colonialist war for what Kissinger actually called “a decent interval” to protect Nixon’s political standing at home. Can there be cynicism greater than that?

How can this be ok? We now know that it would have been possible to end the war in 1969 on the same terms that would finally be reached in 1973. Between 1969 and 1975 more than 21,000 Americans died and hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese apparently for no justifiable reason. Nixon said he did not want to be the first American president to lose a war. President Johnson had said precisely the same thing, and that was central, too, to the geopolitical outlook of JFK.

Historian Stanley Kutler has said, “Certainly the decision on when and whether to end the war in Vietnam was done with a domestic political calculus in mind.” The author of The Vietnam War Files: Uncovering the Secret History of Nixon-Era Strategy, Jeffrey Kimball, concluded that Kissinger’s record “is one of persisting in a deadlocked war for the sake of appearances — i.e. salvaging an elusive and false U.S. credibility.”

Now that Kissinger is no longer alive to protect himself and make life difficult for his critics, the early commentary by journalists, historians, and the punditry class has been surprisingly negative, nearly every obit and article sprinkled with the words “war crimes,” while most politicians are tripping over themselves to sing his praises.

Just how he will be regarded in history (think of his 200th birthday in 2123) is unclear, but it doesn’t look good.