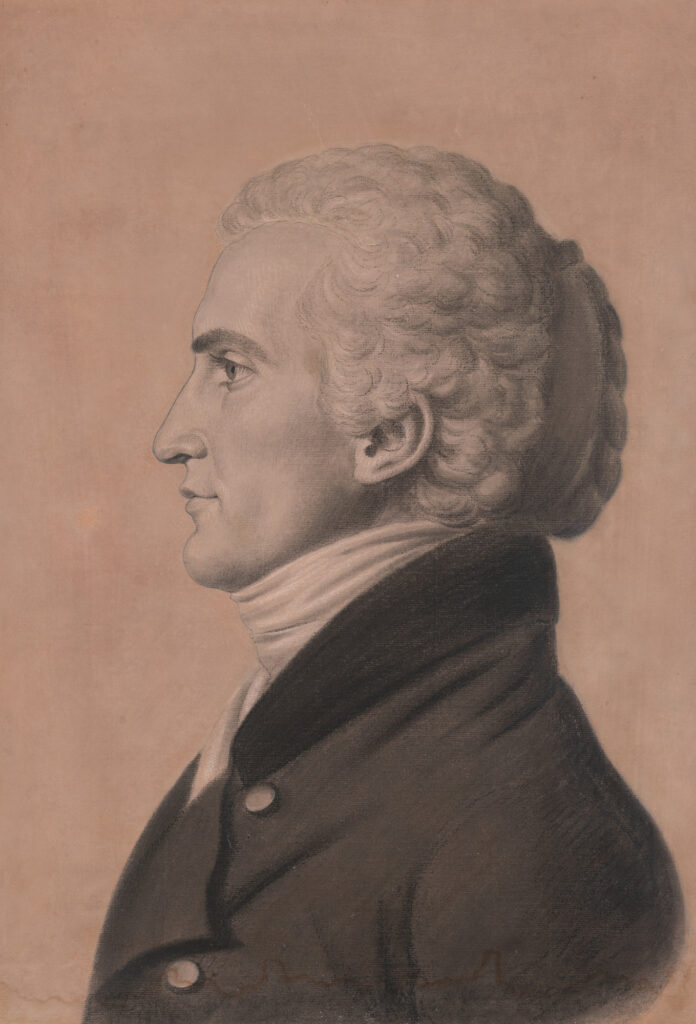

August 18 was Meriwether Lewis’ 250th birthday. The great explorer was born in Albemarle County, Virginia, on August 18, 1774. Unfortunately, he only lived 35 years. Lewis died on the night of October 11, 1809, at a squalid hostel on the Natchez Trace, about 70 miles from Nashville, Tennessee.

I’ve been to the site of his birth, a more or less typical Virginia plantation house that is not open to the public, and I’ve been to the site of his death at Hohenwald, Tennessee. His grave is topped with a broken column, signifying an unfinished life. As you stand there in silence, you can only ask, Why? Why here? Why now?

It seems clear that Lewis committed suicide at that rude inn just three years after his successful journey of exploration from St. Louis, Missouri, to the Pacific Coast and back again. He died of a gunshot wound to the head and another to his abdomen. A fairly large number of people in the Lewis and Clark world want to believe that he was murdered in Tennessee in 1809, but since there isn’t a shred of evidence for murder, since we know that Lewis was profoundly distraught at the time of his death, and since former President Jefferson confirmed his suicide in a public document in 1814, the “murderists,” as they are known, are at a considerable disadvantage in the search for historical truth.

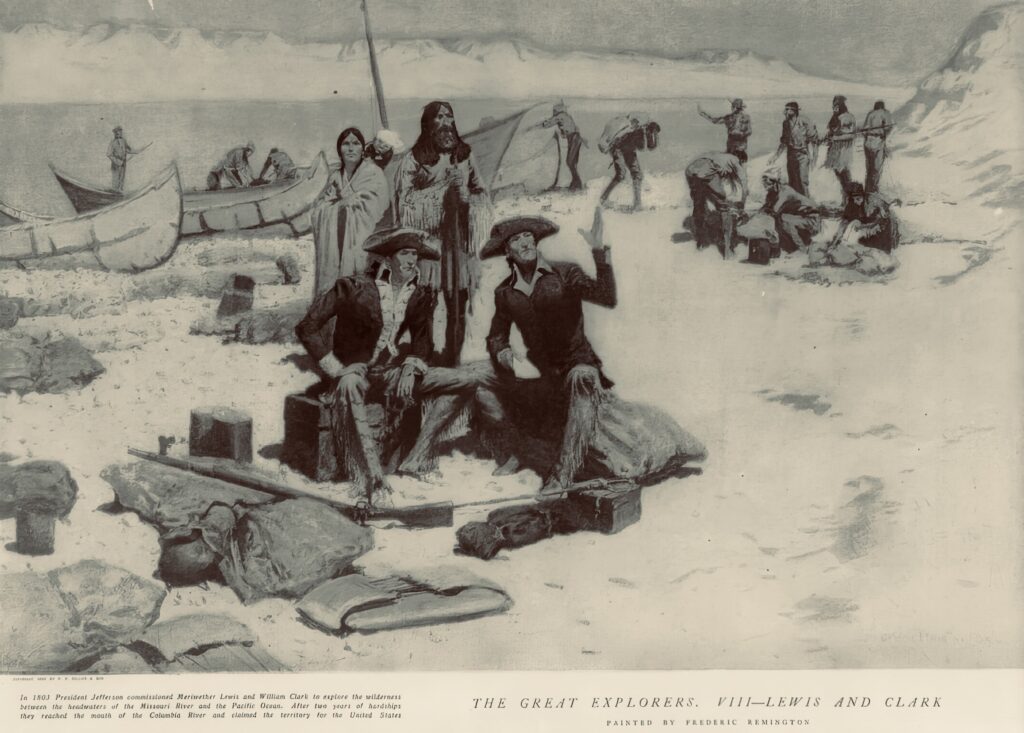

I remember the day when I first read that Lewis had taken his own life. It was in a book by David Freeman Hawke, Those Tremendous Mountains: The Story of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, which I read 45 years ago. I was shocked. In school and Cub Scouts, I had learned a little of the great expedition, but in those venues, the story ended with the explorers returning successfully to St. Louis on September 23, 1806, after traveling 7,689 miles in 28 months. Until that day in 1979, I had never thought about the aftermath — the legacy of the expedition in the history of the westward movement, the contemporary public’s reaction to the journey, including that of President Thomas Jefferson, or what happened in the post-expedition lives of the 33 members of the “permanent party,” in particular Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, Sacagawea, Clark’s slave York, or “the first mountain man” John Colter.

So Lewis committed suicide! Why?

I have literally spent almost half a century trying to understand why. It’s more important to me than the fate of Amelia Earhart, whether Shakespeare wrote his plays or someone else, or the fate of the lost colony of Roanoke. (All of which I find fascinating.) I’ve written two books about Lewis’ death, the second of which, The Character of Meriwether Lewis, I regard as my most important book. Why does a successful explorer, a national hero, the protégé of the great Jefferson, a member of the American Philosophical Society, and the governor of an important western territory (Upper Louisiana) put a gun to his head and pull the trigger when most of his life is before him?

It’s a mystery, and it probably cannot be solved. I have theories. I’ve sifted the evidence again and again and consulted historians, philosophers, psychologists, forensic scientists, and experts who have studied suicide, including Kay Redfield Jamison, the author of Night Falls Fast: Understanding Suicide. I’ve read all 13 volumes of Gary Moulton’s authoritative edition of the Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with painstaking care, searching for clues. The journals (and letters) reveal a gifted, high-strung, self-punishing, mercurial, and volatile young man who repeatedly measured his self-worth with the mission’s success. Many Lewis and Clark buffs (including biographers) say Lewis is not the kind of man who would commit suicide, but when I put that proposition to Kay Redfield Jamison, she said Lewis is precisely the profile of a person who might commit suicide.

The least speculative way to describe what happened might be something like this: Lewis had boxed himself into a corner in the years after the expedition’s return, and at that lonely hut on the Natchez Trace, he saw no way out of his troubles. He felt he was by now all alone in the world. Clark was no longer a daily prop. Lewis has never married or had a relationship with a woman, as far as we know. At the moment of his death, Lewis was 618 miles from his mother, Lucy, back in Virginia and almost precisely the same distance from his mentor, Jefferson, who retired at Monticello and had reason to be disappointed with his protégé. Lewis had no God. He had failed to write his projected book about the expedition, and Jefferson was grumpy about that. His personal finances were in complete disarray, and his public finances as Governor of Upper Louisiana were being sternly contested by the U.S. government, which had essentially accused him of a conflict of interest in how he handled public moneys. Lewis was ill with malaria (a common frontier malady). He was drinking heavily, and he had what we would call an opioid addiction (laudanum). As a young man obsessed with his honor, he was appalled, outraged, and devastated to think that the War Department could challenge his integrity.

When the deed was done, and the news from the frontier reached first Clark and then Jefferson, these two men closest to Lewis were shocked but not surprised. Clark famously wrote, “I fear O! I fear the waight of his mind has over come him.” Clark knew Lewis better than anyone on earth, and he recognized him as a brooding melancholic who had been coming apart during his last months as territorial governor in St. Louis.

Almost every suicide is a mystery in some sense. Why does this one matter so much?

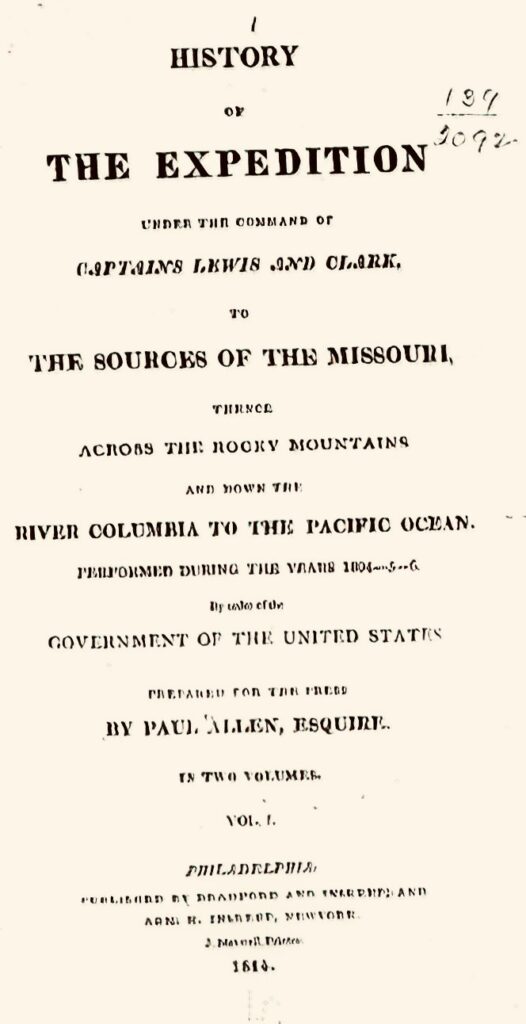

First, Lewis had not finished his book. We have some of his journals, which seem to have been rewritten after the expedition as a draft of the book he was trying to write. Still, by clocking out at 35, he withheld from the world the tens of thousands of words and scores of important insights that would have served as an Enlightenment capstone to the journey. Clark picked up the pieces and got something into print in 1814 (eight years after the return), by way of a ghostwriter who never ventured into the American interior. However, we all know that Lewis’ account would have been dramatically richer had he fulfilled his responsibility. What knowledge, observations, reflections, insights, predictions, and recommendations died with Lewis? Incalculable.

Second, if Lewis had lived to a ripe old age, he would indeed have gone on to other great achievements. Clark served as a St. Louis-based adviser to every serious mission (commercial, military, or scientific) that ascended the Missouri River between 1806 and 1838. Had he lived, Lewis might have been the nation’s principal adviser on frontier development. And who knows what Jefferson had in mind for him? Jefferson collected and promoted protégés. Two of them — James Madison and James Monroe — went on to be presidents of the United States. There is no reason to doubt that Jefferson might have been grooming Lewis for the U.S. Senate — or more.

Third, it is unlikely that Lewis’ suicide is entirely unrelated to the great journey he undertook into the American heart of darkness. Some, including the late Stephen Ambrose, have argued that there is no linkage between the journey and Lewis’ death. Perhaps. But it seems to me much more likely that his suicide was a ramification, a response, or a reflection on his experience in the wilderness. The way I put it in my book is that Meriwether Lewis and William Clark made the same trip between 1804 and 1806, but in some essential way, a different journey. What happened to Lewis out there? The great essayist Barry Lopez once responded to that question by saying, “How far can you go out there and still come back?” That seems to me a key insight, perhaps the key insight.

We don’t know enough to work that question to a satisfying conclusion, but I believe it will be impossible to understand Meriwether Lewis, the Lewis and Clark Expedition, or the Americanization of the continent without working hard to make sense of that question. In other words, the tragedy of Lewis is in some way the tragedy of America, but it is also an opportunity for us to work harder to rethink western history as the 250th anniversary of the United States approaches.

In puzzling Lewis’ death, we should not lose sight of his achievement or greatness. He took several dozen men (and a woman and child) all the way out and all the way back with the loss of only one of his men (natural causes). As a protégé of Jefferson and a figure of the Enlightenment, Lewis gathered an enormous quantity of data and organized it thoughtfully. His relations with Native Americans were, on the whole, exemplary. And when he was writing in his journals, his prose was the best of all the extant writings (journals, letters, reports, publications) by magnitudes.

Jefferson was right to entrust the mission to Lewis. And Lewis was even righter to invite William Clark to be his full partner in discovery.

The mystery abides. If I live 30 more years, I will be able to report, from dotage, that we still don’t quite know why Lewis ended his life on October 11, 1809.

P.S. I thought you might wish to read Lewis’ birthday entry from the expedition’s journals (August 18, 1805), which gives you a sense of how self-punishing he could be.

Meriwether LewisThis day I completed my thirty first year, and conceived that I had in all human probability now existed about half the period which I am to remain in this Sublunary world. I reflected that I had as yet done but little, very little indeed, to further the hapiness of the human race, or to advance the information of the succeeding generation. I viewed with regret the many hours I have spent in indolence, and now soarly feel the want of that information which those hours would have given me had they been judiciously expended. but since they are past and cannot be recalled, I dash from me the gloomy thought and resolved in future, to redouble my exertions and at least indeavour to promote those two primary objects of human existence, by giving them the aid of that portion of talents which nature and fortune have bestoed on me; or in future, to live for mankind, as I have heretofore lived for myself. —

August 18, 1805

On the Montana-Idaho border