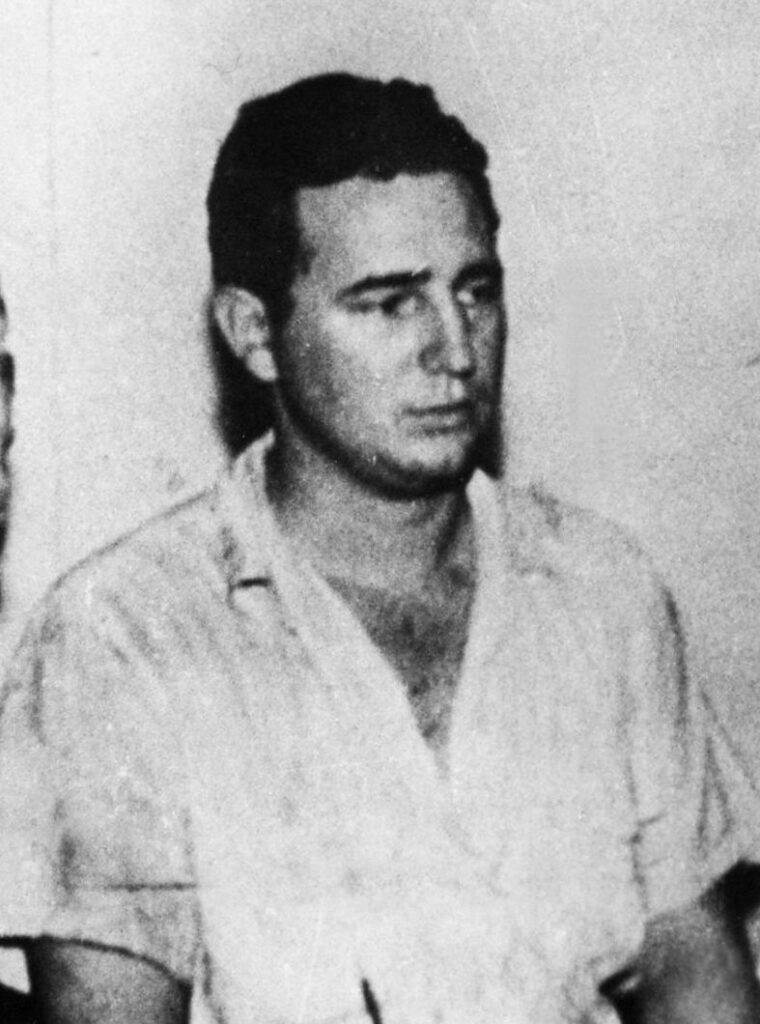

Fidel Castro’s birthplace, now a museum, is one of the initial stops for Clay and his companions as he leads a cultural tour of Cuba.

When we finally got through passport control and customs at the Holguin Airport in eastern Cuba and boarded our Chinese-made bus, our outfitter announced that he had arranged a visit to the boyhood home of Fidel Castro near the village of Biran. I asked him to organize this a few weeks ago, but he informed me we’d get to the ranch’s vicinity after the staff went home for the night. But our Cuban guide, Marlin, contacted the staff a few days ago, and they graciously agreed to stay open for us. Try that at Best Buy or the Guggenheim.

It turned out that we were the first Americans to visit this site in more than three years. The Cuban tourism industry, vital to the struggling Cuban economy, has been on life support for the last seven or eight years. The topsy-turvy caprice of American foreign policy towards Cuba creates a perpetual instability that makes it difficult for the travel industry to attract guests and maintain steady services.

In her 1963 book On Revolution, the German philosopher and journalist Hannah Arendt argued that most revolutions do not percolate up from the people. They are fomented and led by passionate advocates of the upper classes: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Vladimir Lenin, Ho Chi Minh, and even Gandhi. Those privileged and well-educated men initiate revolutions on behalf of the people. In many cases, those comparative aristocrats lose control of the revolution (and sometimes their heads), and events take populist and often enough violent turns.

By Cuban standards, Fidel Castro (1926-2016) was born with a silver spoon in his mouth. His father, Angel Castro, was originally from Spain and was a great entrepreneur. By dint of hard work — and the relative exploitation of Cuban peasants — Angel created a little economic empire for himself at Biran: a significant sugar plantation, a modest pharmacy, an elementary school, a hotel on the important Camino Real (then not much more than a cart and horse path), and a cockfighting ring.

His (illegitimate) son Fidel was a headstrong, opinionated, occasionally violent youngster, eventually privately schooled because he was too much trouble for the public school in his neighborhood. He studied law at the University of Havana, where he became radicalized and read deeply in the history of revolution and Latin America. At one point, he attempted to organize his father’s workers to strike for better wages and working conditions!

Some of the Castro buildings have been rebuilt over the years — the ranch is now a working museum and, for Cubans, a sacred place — but the cockfighting ring is original, though a horned bull was doing its best to demolish the picket fence by rubbing hard against it. In the distance, we saw a man plowing with a single moldboard dragged slowly by an infinitely patient ox. It was a scene out of Homer’s Odyssey, 330 miles from Miami, as the crow flies.

Fidel’s cradle is on prominent display on-site — the cradle of the revolutionary and revolution. There is a kind of sweetness to this. It is hard to imagine the man who could deliver a four-hour harangue to the Cuban people and defy and browbeat 10 successive American presidents as a humble child.

We did not linger, not wishing to keep the staff any longer than necessary. A haze or slight fog had set in by the time we left. Several members of the staff commuted home on horseback. Everything on the extensive property was bathed in soft light, the sun setting quietly in the west, the boyhood home of one of the world’s great revolutionaries.

We loaded up the chief interpreter at Fidel’s boyhood home with small American amenities — individually wrapped soaps, motel-sized shampoo, toothbrushes and toothpaste, razors, etc. Such small and inexpensive items, travel-sized on display at Dollar Stores and Walmart, are a godsend for the Cuban people, who lack the most basic services and amenities.

Our purpose in seeking out Fidel Castro and Castro Revolution sites in Cuba is not to celebrate the passionate and often bombastic Castro, who did good things for his people (literacy, health care, women’s rights) but also was capable of arbitrary detentions, press censorship, postponed or canceled elections, one-party rule, and torture and executions during his long reign (1959-2008). We are following his 1953-1959 revolution across the island because Castro became a world-historical figure. He stood up to the colossus to the north. He inspired (and continues to inspire) millions of oppressed people worldwide. There are thousands of murals and billboards celebrating Castro throughout Cuba. Few here are unaware of the dark side of Castro’s reign and the failures of his semi-communist government. Perhaps he stayed on the stage too long. Perhaps, like other revolutionaries (with the magnificent exception of George Washington), power and hubris corrupted him. But he liberated Cuba from American commercial colonialism, and that continues to matter directly to the soul of the Cuban people.

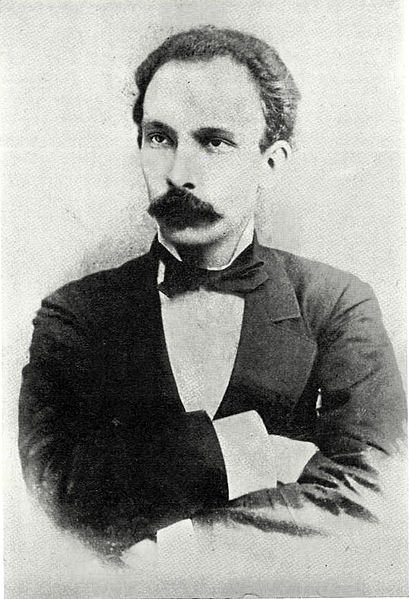

In Cuba, the great hero is José Martí (1853-1895). Fidel comes second, and even those who have long since become disillusioned by his ways and rule still maintain reverence for him. Third is Che Guevara (1928-1967), who was not a Cuban but an Argentine, a serious Marxist intellectual, but also a physician, guerrilla leader, diplomat, author, and military theorist.

We drove quietly towards Santiago through sugar cane fields, the majority of them now idle, past rusted out sugar cane harvesting equipment, on roads in which the asphalt is breaking up into unstable gravel.

No matter what our individual politics were, we all felt a kind of sentimental pleasure in visiting the site of Fidel Castro’s formation. It was dark at the Hotel Imperial in Santiago when we finally arrived, tired, intrigued, hearing our minds grind and open with new perspectives, observations, and insights.