A visit to his “wee cabin” outside of Yellowstone reminds Clay of John Locke’s comment, “In the beginning, all the world was America.”

On my way back to North Dakota from Vail, Colorado, I planned to stay a few days in my modest cabin 2 miles from Yellowstone National Park near Cooke City, Montana; I decided I needed to make a pilgrimage to Old Faithful. Whenever this impulse seizes me, I always sigh a little because visiting Old Faithful is a bit like visiting Mount Rushmore or Disneyland: traffic, parking, crying and whining children, splotches of ice cream accidentally dropped from cones all over the site, expensive hot dogs and mindless souvenirs, and displays of the full range of human nature.

But Old Faithful is one of the Wonders of the World. It is the centerpiece of the most concentrated array of geysers on Earth. It is one of the quintessential American experiences. In any list of must-see American places — the Grand Canyon, the Statue of Liberty, the Lincoln Memorial, Monticello, Canyon de Chelly, the Golden Gate and Brooklyn bridges, Sunset Boulevard, the Empire State Building, Wounded Knee, the Little Bighorn Battlefield, Gettysburg, the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma — Old Faithful has a place near the top. There was no way I was going to talk myself out of it. When I was here with my near kin on the 4th of July once a dozen years ago, I brought up the idea of going to Old Faithful to celebrate American independence. My mother and daughter groaned — hours in the car, congestion, traffic jams. They didn’t veto the pilgrimage — they didn’t dare — but they were hoping I would back down. “Get in the car; you’ll thank me later,” I said. They did. And they did. We had a magical day.

I’ve been to Yellowstone National Park, established 1872, the first of America’s national parks, several dozen times. But I don’t know it very well. I’ve hiked at most 20 miles along the park’s network of trails. I know a little about how it was “discovered” and later enshrined in American law, how Theodore Roosevelt and George Bird Grinnell — Boone and Crockett Club members — saved the park from adverse industrial development. I know that the park — large at 2,219,790 acres — is only a small parcel of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (20 million acres), which contains the habitat that wolves, bears (including grizzly bears), bison, elk, bighorn sheep, and other creatures need to thrive. I know that Yellowstone National Park is the height of land from which mighty rivers take their source: the Yellowstone, the Snake, the Shoshone, and the Madison and Gallatin, prime arteries of the Missouri River.

You could spend the rest of your life mastering Yellowstone National Park: its origin story, history, relation to Native Americans, hydrology, wildlife, trees, mountains, geothermal wonders, serious, possibly even existential challenges, hikes, and trails.

Heck, I don’t even really know the small plot of forest on which my wee Cooke City cabins sit. There are hundreds of trees (mostly evergreens — you see how vague I am), shrubs, and wildflowers. Just to the north, there is a steep mountain (whose name I don’t know) that I have thought of climbing, but so far, I have never done so. An occasional bear visits the property. My sister claims she walked out once, and a grizzly was lounging in a deck chair — but my sister told some stretchers, as Huck Finn says. Whenever I am at the Walden Cabin, I see one or more foxes that turn up around dusk, sit on the grass outside my window for a few seconds or minutes, and then resume their rounds. At this time of year, there are scores of butterflies. Henry David Thoreau would know the exact perimeter of his property, would make an inventory of all the species that live on the small plot of forest, would get down on his stomach to observe a delicate wildflower, would harvest edible plants, find a way to talk fox, and would know just when the afternoon thunderstorm is likely to move through.

The first thing I did after my mother died five years ago was remove the television from her cabin. I got rid of the satellite dish. And her huge and diverse collection of refrigerator magnets.

Yesterday, I approached Yellowstone National Park from Cody, Wyoming. I usually come from Billings or Bozeman, but this time, I decided to enter the park through the East Entrance (U.S. 20, U.S. 14). Each of the five entrances to the park is spectacular in its own way. Driving over the Beartooth Highway (U.S. 212) is one of America’s most thrilling mountain highways, and for some (like my late father), terrifying. Driving down U.S. 89 to the North Entrance with the Roosevelt Arch makes you want to ban second-home ranchettes unless, of course, you have enough money to buy one for yourself. It’s always a joy to see the Yellowstone River when it is still a boisterous mountain stream. But if you want to see what can go wrong in American tourism, I recommend West Yellowstone.

To get to the East Entrance from Cody, you have to go through a wonderful highway tunnel — it has some of the feel of Alice Through the Looking Glass or Harry Potter and his friends getting on board the Hogwarts Express — a magic portal to one of the world’s most magical places. The Shoshone River is dammed near Cody, and the reservoir behind it is not one of America’s most beautiful, but the closer you get to the park entrance, the more amazing the Shoshone becomes until you almost forget Buffalo Bill Cody’s obsession with making the desert bloom, with a little help from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. As you approach the park, you inevitably say, “Why isn’t this also part of the national park?” It’s some of the most sublime scenery in America.

Not long after I entered the park, I saw 40 cars parked awkwardly by the side of the road. Scores of people were standing on the edge of the pavement with their gigantic telephoto lenses, professional binoculars, and tripods with spotting scopes. I know a good “mediated experience” when I see one, so I stopped, too. I walked up quietly to one cluster of people studying the mountainside as if it were a medieval Chinese manuscript. I did not want to be one of those people who rush up saying, “What are we looking at?” but I trust human nature, so I waited a couple of minutes until someone else asked the question.

“It’s a grizzly bear,” a man said, “but it’s hiding. It’s shy. It’s been behind some of that fallen timber for the last 15 or 20 minutes. We’re hoping it will show itself before long.”

I looked up at the putative site of the grizzly. All I could see were approximately 350,000 dead, downed trees, making the mountain look like the cosmic edition of Pick Up Sticks or a box of colossal Lincoln Logs unceremoniously dumped over the steep terrain. “Start from the bottom right next to where the guy in Bermuda shorts is standing and work your eyes up about 100 yards up the mountain where one of the most dense patches of fallen trees is,” said the man. “We think that’s where it is.” I did my best, but I eased my way back to the car since there were hundreds of dense patches of fallen trees on the mountainside, and the alleged grizzly bear was invisible. As I withdrew, a woman said, with the greatest sense of conspiratorial pride, “The rumor is that it’s Raspberry.”

Raspberry?

I looked this up later, and I’m sorry to report that there are bears in Yellowstone who have been given pet names by photographers and bear watchers. These bears have been “adopted” by their fans, who generally know where to find them and who spend days, weeks, even months looking out for their foster quadrupeds, speaking a kind of wilderness baby talk to them, photographing them with lenses that cost thousands of dollars, cooing and ahhing, sending triumphant texts, and letting mere tourists know that they feel a fiduciary responsibility to make sure the bears are thriving.

Naming a Grizzly Bear?

This would seem to me to violate the very idea of wildness. To name is to possess. Why call a grizzly bear Petunia or John Muir? Whenever we anthropomorphize the Other — other species, plants and trees, domesticated animals — we succumb to the trap of believing that humans are the measure of all things and that we have dominion over species lower down the great chain of being, that we are entitled to name them like our dogs or cats or parrots. We should want wild creatures to be … well, wild. Nameless, uncooperative, Other, and a little dangerous. We should revel in the fact that so many of God’s creatures live their lives all around us with little or no regard for human beings except to find them intrusive. I was thrilled during the pandemic when the national parks closed, and all the human-shy species came back down to reclaim Yosemite Valley, Glacier, Yellowstone, Chaco Canyon, and scores of other national parks and national monuments.

But to each her own, of course.

I drove the northern perimeter of Yellowstone Lake (huge, the “source” of the Yellowstone River) and followed the directions to Old Faithful. I found a good parking spot near Old Faithful Lodge. I locked the car (alas) and walked up to the giant semicircle of backless synthetic benches where people gather to wait for Old Faithful to vent. It was a mid-June Friday. Approximately 1,500 people were sitting to wait for the geothermal show.

I had no idea when Old Faithful was scheduled to vent, and I did not wish to know. The not knowing is part of the ecstasy when it happens. But there were impatient time-keepers all around me consulting their watches and websites. For the first 45 minutes, the visitors were quite subdued. It was the first truly great summer weather day in 2024 for most of us. Temperature 74 degrees, a light breeze, scattered cumulous clouds, a blue, blue sky, and we were joined in a community paying homage to one of the Wonders of the World. I sat serenely without a care in the world in one of the world’s great places, thinking Ken Burns was right: national parks are one of America’s greatest ideas. The crowd mostly spoke mutedly, as if they sensed this was an American cathedral. It seemed to me that the people who had gathered on the longest day of the year were feeling the need to experience something to be proud of and cheerful about in this horrific time of savage politics, governmental paralysis, and a down-in-the-dirt rematch between two antiquated political veterans that polls show the American people have no passionate attachment to.

Finding Optimism About America Again

I need to find hope and optimism about America again. I love America. I am in love with America. I believe we Americans were intended to be the exemplars for the world of what life can be when people of the Enlightenment fashion a republic “of the people, by the people, and for the people.” We were meant to be a Periclean people, cherishing truth, beauty, justice, and the arts of civilization with ideals higher than materialism and mere prosperity. I want to believe that we are one of the most enlightened peoples on earth, that we are, on the whole, a force for good in the world, and that the world is better off for our existence and global leadership. I want to believe that we are not finished, but continually and measurably moving toward “a more perfect union,” that the founding ideals of America — equal treatment before the law (no man above), due process, checks, and balances, limited government, equal justice to every human being, self-reliance, civility, compassion for those who fall through the cracks of our advanced capitalist economy, sympathy for the “wretched” refugees of the world and especially the western hemisphere, a deep national dedication to peace, unlimited religious and ethnic tolerance, a living wage for every hard-working American — can be reburnished in a time of disillusionment.

The great Wallace Stegner (1909-1993) said it best. We need America “to create a society to match its scenery.” There is still time, but we will have to rededicate ourselves to the challenging quest.

Something is wrong when the Right has a monopoly on the rituals of patriotism — flags and Lee Greenwood! — and the Left seems embarrassed to stand for the national anthem, pledge allegiance, sing America the Beautiful, or express their love of country. Many on the Left are afraid to declare their patriotism or their love of America because they believe they will be ridiculed as saps, sentimentalists, rednecks, or insufficiently critical of America’s many failures of justice for all. But America belongs to us all.

I had now been sitting for a full hour on the backless bench. The crowd’s patience began to erode as the temperature rose a few degrees, and the geyser did not quite conform to ranger predictions. One grumpy woman declared that Old Faithful wasn’t worth a heat stroke, for Christ’s sake, and that she would seek some shade and maybe come back once she saw the vapor plumes. A wise guy a few rows back said why couldn’t the national park find a way to make Old Faithful go off every 30 minutes right on schedule, or at least provide an app so we could be sipping beer in the bar until we were alerted to the geyser’s imminent eruption.

Then it happened. A zillion smartphone photographs were taken, many awkward selfies, and some phone videos. Very few dedicated video cameras are out there these days, but I can remember when they were the size of luggage. Old Faithful spouted for a couple of minutes and then settled into some aftershocks. Some people clapped. Everyone stood up and made for the parking lot.

An older man from one of the Dakotas was pretty uninspired. “That’s it? That’s the Old Faithful I have been hearing about all my life? I drove 600 miles for this? I thought it would be better.” His wife, glancing around, said, “Well, maybe this was not one of its best days.” A young father said, “If we hurry, we can beat the line at the cafeteria. Let’s bounce.” A bored teenager said, “Will there be internet tonight in the campground for once? And how far is it anyway?”

I wanted to turn to them all and do some comic mansplaining. “Hey, you knuckleheads, this is one of the Wonders of the World. Geez. What would it take to impress you?! Yellowstone National Park is the world’s premier geothermal zone. You were reminded that the Earth is a dynamic sphere, not inert, that all sorts of wild stuff is happening below the surface everywhere, but in a few places, it vents its way out. Yellowstone was the world’s first national park. It changed everything. Thanks to the foresight of Congress in 1872, Yellowstone served as the template and the precedent for national parks all over the world, including 63 full-on national parks in the United States, including Great Smoky Mountains, the Everglades, Crater Lake, Big Bend, Mesa Verde, and in North Dakota, Theodore Roosevelt National Park, named in honor of the greatest presidential conservationist in American history. And, you jaded folks, Old Faithful faithfully vents 20 times daily with something like uncanny regularity. You can take your app and …”

But of course, I said nothing. I slunk away.

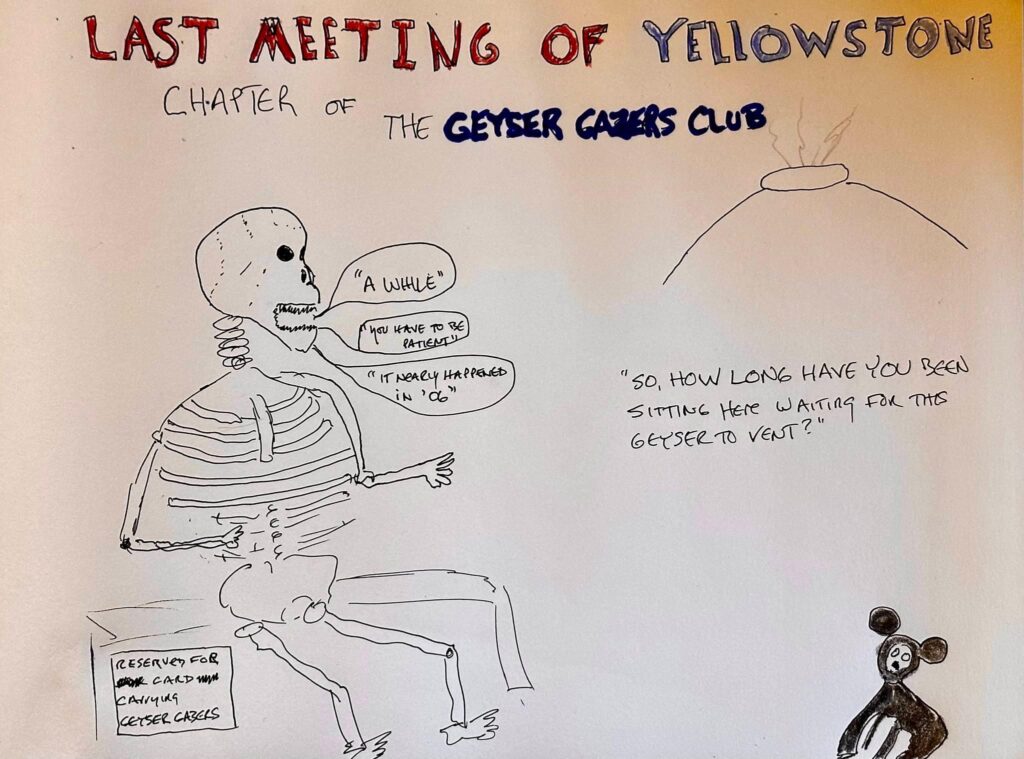

The Geyser Gazer

I decided to do the boardwalk hike (stroll) around the geyser basin. Because we are so over-conditioned and over-mediated for Old Faithful, the lesser geysers are actually more fascinating because happening upon one feels more like discovery and less like a culture cliché. I stopped to look at a couple dozen thermal pools, vents, baby geysers, and other geothermal anomalies, sharing other visitors’ sense of awe, and I was on my way back to my car — still two and a half hours from my cabin — when I approached Lion Geyser on the boardwalk. A young couple (in their late 30s) were sitting on the bench intently watching the small array of geyser vents. I sat at the other end of the bench, not wishing to interrupt their time together or their vigil. But the man soon turned to me and told me that Lion was expected to vent sometime in the next 90-180 minutes, that it is one of the most impressive geysers in Yellowstone, and that an hour and 10 minutes after its big performance, it has amazing aftershock rumblings that sound precisely like a lion. He wore Keene hiking boots, shorts, a green checked shirt, an REI hiker’s hat. He had guidebooks in his backpack, snacks, binoculars, and maps. He had a scratchy beard. The woman with him was dressed more for the golf course than for a geyser basin, but she seemed content to be there.

I decided to join the vigil.

My new friend explained that geyser watching was his “hobby,” though his girlfriend suggested that “obsession” was perhaps a more precise description. She had a paperback book in her pack, a quasi-bodice ripper, and she retreated into that alternate universe for chunks of time. He had a walkie talkie. Every 20 minutes or so, the device would crackle with updates from other geysers. “Unit One to Unit Four. The Eagle has landed.” That sort of thing. He explained that he belonged to a group affectionately known as Geyser Gazers (who knew?), that there was a website and an online and (if you pay more) print edition of a periodic newsletter. He had an app on his phone that let him key in data from any geyser anywhere. They are crowd-sourcing a complete global chart of geyser behavior and periodicity. He has written for the online journal. I asked him approximately how many Geyser Gazers there are in the world. Hundreds or thousands? Low hundreds, he said. I asked if they had annual conventions. Not anymore. Not often.

I asked questions about how geysers work, and the young man answered them with real clarity. After about five minutes of basic scientific explanation, he looked up at me and said, “Basically, it’s like a tea kettle when it boils over.” That much, of course, I knew. I asked him if it is still the case in Iceland that “guides” salt geysers with laundry detergent to make them vent. Not so much anymore, he said. I asked him where the other great geyser basins of the world are. Iceland and New Zealand. Oh, and west of Cody. And one that has been quiet for a long time in Nevada.

We did not talk much. I sat there — enjoying the sun, the breeze, and my Geyser Gazer while musing, meditating, and thinking about America. Every 10 minutes or so, one of the four vents in the cluster did something interesting. He “read” the geothermal rumblings with years of gazing under his belt. “That was a good sign,” he said. “It won’t be so long now.” The geyser known as Little Cub never shot more than 8 feet high, and usually about 5 or 6, every 20 minutes or so, but I found it fascinating, in some ways more than the most impressive geysers. “The Earth is alive with energy!” my Gazer guide gushed. About two hours in — beginning to wonder how my day or night would end — I must have let out an audible sigh. From the other side of my Geyser Gazer, his girlfriend said, in a low tone, “Yeah, there’s plenty of that.” But he was not offended.

The sun was about to set. I had to leave. I had so wanted to show the kind of patience I would need to earn my Geezer Geyser Gazer badge. Standing, I said, “I am going to do you both a great favor. I have to leave, and I know the minute I leave, Lion is going to blow.” He chuckled and said, “That’s how it works.” I asked, “Just out of curiosity, how long have you been here this afternoon, and — more to the point — how long are you prepared to maintain this geyser watch?” “We’ve been here four hours,” said he, “and my sense is that there’s no point now in walking away. It’s got to vent in the next hour or so.” I was tempted to stay, but I reckoned he might say much the same thing at 8:45 p.m. I walked toward my car.

Five minutes later, I turned back like Lot’s wife. Sure enough, the Lion was roaring. Later that day, I told an old friend about it, and she said, “You would have so enjoyed watching his face when it happened.” She was right.

The traffic was light as I drove from Old Faithful to Canyon, Canyon to Tower, and Tower through the Lamar Valley to my cabin, situated midway between Cooke City and Silver Gate on U.S. 212. I drove slowly, in a lovely patriotic national park haze, window open, sound system muted, air temperature dropping 2 degrees every 15 minutes, the quality of light gentling its way toward dusk. I drove past hundreds of buffalo and some elk.

When I opened my cabin and put a few things in the refrigerator, I poured myself a glass of pinot noir and sat out on my deck, waiting for the foxes. They came. Then they left. I stayed out until it was too dark and chilly to linger.

I felt great love of America.

We are incredibly fortunate that men and women with foresight and wisdom have set aside some of the primordial New World for permanent protection from adverse economic development. How great that we have saved some of the best of America — for seed. How great that we understand that some of the best things in existence must be left alone and not forced onto the Procrustean Bed of human selfishness. We will have to face the issue of how many visitors are enough per day, week, month, and year. We are loving our national parks to death. They are our spiritual refuge. They remind us of the wisdom of John Locke, when he said, “In the beginning, all the world was America.”

Note to self: get here more often.