“Who hears the rippling of rivers will not utterly despair of anything.”

Henry David Thoreau

Part One: The Best Laid Plans

Every summer I lead a cultural tour on the Lewis and Clark Trail in Montana and Idaho. Usually, we canoe through the White Cliffs section of the Missouri for a couple of days, regroup, head west, and then climb up the “Wendover Death March” to the ancient Lolo Trail along which Lewis and Clark slogged their way to navigable waters of the Columbia River system. But occasionally we switch things up by floating the Salmon, the “River of No Return.” This was such a summer. We usually put in at Corn Creek and take out at Riggins, Idaho.

We gathered in Three Forks, Montana, where we stayed at the Sacajawea Hotel. Meriwether Lewis named the three forks of the Missouri for members of the Jefferson administration: the Madison, after the secretary of state, the Gallatin, after the secretary of the treasury, and the Jefferson, after Lewis’ patron, the third president of the United States.

The Sacajawea Hotel. Here’s the short course on how to name and think about the Native American woman who accompanied Lewis and Clark from the Mandan-Hidatsa villages to the Pacific (and back). In western Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming, she’s called SACKaJaWEa, and her name seems to mean “she who pushes” or “she who carries burdens.” In most of Montana and in the Dakotas she is known as Sah-KA-ga-WE-a, which translates as “Bird Woman.” The official pronunciation in America is now Sah-KA-ga-WE-a, and the overwhelming consensus is that she was born Shoshone around 1787, was captured by a Hidatsa raiding party when she was perhaps 11 or 12 years old, taken to the Hidatsa villages on the Knife River in today’s North Dakota where she was absorbed into the Hidatsa world. When Lewis and Clark met her, on or near November 4, 1804, she was pregnant. Lewis named a tributary river in Montana after her on May 20, 1805. That was when he explained how to pronounce her name and laid out what little he knew of her origin story.

The Sacajawea Hotel served us champagne when we checked in.

As we prepared for dinner on the night before we embarked on the river, we got a call from our outfitter Wayne Fairchild in Missoula announcing that the U.S. Forest Service had just closed the main reach of the Salmon because of a forest fire there. This was disturbing news, since we had 25 people from all over the country who had paid a considerable amount of money to take this raft trip. What to do? Cancel and try again next year? Ditch the river and do a more traditional Lewis and Clark bus tour? Or find another river?

Wayne Fairchild has owned Lewis and Clark Trail Adventures for decades. He’s as dedicated an outfitter as one could ever ask for. I would feel much less comfortable using any other outfitter on the Salmon and particularly on the Missouri. As long as he has cell service and a team of young rapscallions ready to fan out across the landscape, Wayne can make just about anything happen. His flexibility is legendary. I’ve never seen him fret in a crisis. He invariably says, “On it!” and finds a way.

Before we could even divulge the situation to the registered participants at dinner, Wayne had solved the problem. He got an emergency temporary license to launch farther west at Hammer Creek and take out at Heller Bar. We’d be floating the lower Salmon not the main. There was no fire threat in the lower Salmon. The river was open. So far so good. Then, rather than driving us to the new put-in point in a yellow school bus, Wayne rented enough SUVs to get us there without rattling our bones. It was a perfect bonus amenity for our participants, who were naturally a little nervous about how this adventure would play out. The crew and the rafts were repositioned at the new put-in site.

It seemed effortless. Wayne works his miracles because he is a resourceful and disciplined man. But also, because he has made a career of treating other outfitters, hoteliers, rental car agents, and law enforcement agents with respect. He plays by the rules of the rivers. He has a reputation for integrity. He’s paid it forward countless times when another outfitter gets into a jam. In other words, he’s built up a lot of goodwill. When he needs help, other good folks who belong to the river community don’t hesitate.

Tell him what you need.

“On it!”

Looking back on the river trip, you’d be hard pressed to be aware of anything out of the ordinary. We launched on the Salmon River just as we had planned for more than a year — just at another put-in point downstream. Nothing was left behind in the scramble except one participant’s dry bag. What looked like a disaster at the Sacajawea Hotel became a seamless adventure. When I think of the ways in which this could have been a disaster or a disappointment, I shudder.

No Salmon on the Salmon

The great dams on the Columbia and Snake rivers may have helped the United States win World War II, but they decimated and nearly destroyed the salmon runs on the Columbia and its tributaries. The old cliché was that before the dams you would walk across the Columbia on the backs of salmon. Today the Salmon River has virtually no salmon. This is partly because of the laws of unintended consequences — the dam advocates were thinking of power, navigation, irrigation, but not fish — and partly because the steps taken to preserve the salmon runs — fish ladders, fish hatcheries, trucking smelt around the dams, etc. — have not been very effective.

The same paradox haunts the landscape through which the Missouri River flows east of Fort Benton, Montana. It looks pristine; some visitors say it could be 1805, it feels that the Lewis and Clark flotilla could round the bend in the river at any time. But once you begin to reckon what has been erased in 200 years — buffalo, grizzly bears, wolves, elk, Native Americans — that arcadian trope begins to break down. Even many of the grasses are transplants from Eurasia.

The Salmon River system drains a huge watershed, one of the wildest and least densely populated parts of America. The river is 425 miles long, depending on how you count, since there are a number of important forks along the way. The Salmon drops 7,000 feet from its headwaters. It is sometimes called the longest undammed river in the American West. That’s not precisely true of the Salmon, just as it is not precisely true of the longer Yellowstone, which is mostly but not 100% undammed. But compared to the Colorado, the Snake, the Missouri, and the Columbia, the Salmon is wonderfully uncompromised by America’s love of concrete.

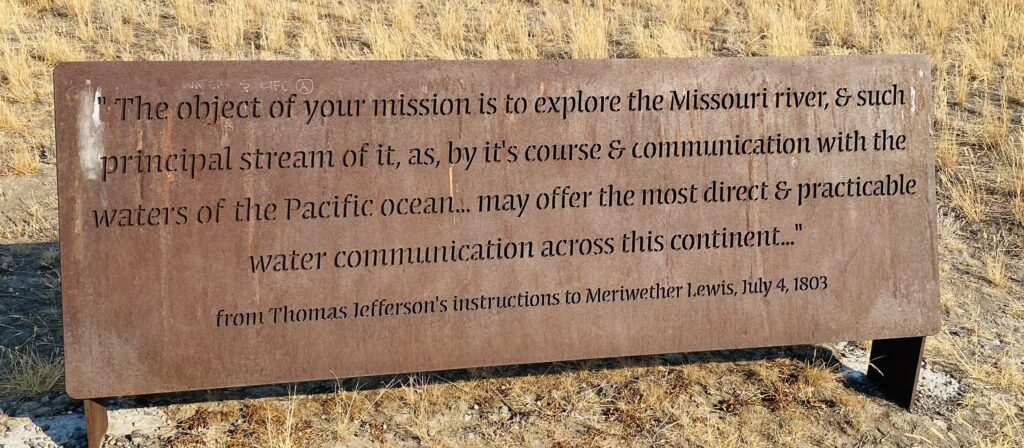

Lewis and Clark were instructed by Thomas Jefferson to follow the Missouri all the way to its source, portage over whatever mountains separated it from the Pacific watershed, then find navigable waters of the Columbia (the River of the West) and float down to the ocean. They were hoping that the river on the west side of Lemhi Pass (7,373 feet) would be as navigable as the Jefferson-Beaverhead tributary of the Missouri on the east side. What they discovered, however, was that the Salmon would not cooperate! It was too shallow and full of rocks and rapids to be floated anywhere near Lemhi Pass, and when Clark ventured a few days down into the Salmon watershed, he discovered that the river was hemmed in on both sides by nearly vertical cliffs. The Salmon was, in short, unsuitable for their purposes. In the end, they had to bushwhack north all the way up to today’s Lolo (near Missoula) before they found a trail that could take them far enough west to find navigable waters of the “Columbia.” At today’s Orofino, Idaho (Canoe Camp), they finally found the trees they needed to make dugouts and enough water to float them. By now they were in the Lochsa-Clearwater-Snake branch of the Columbia River.

If Lewis and Clark had found an easy portage, they would have been able to confirm to Mr. Jefferson that they had discovered “the most direct & practicable water communication across this continent for the purposes of commerce,” as the president put it in his famous instructions of June 18, 1803. In other words, the fabled Northwest Passage. When he got back to St. Louis in the autumn of 1806, Captain Lewis had to report that “the passage by land of 340 miles from the Missouri to the Kooskooske [Clearwater] is the most formidable part of the tract proposed across the Continent; of this distance 200 miles is along a good road, and 140 over tremendious mountains which for 60 mls. are covered with eternal snows.”

So much for the Northwest Passage.

The Salmon has several deep gorges. They seem to beg for giant hydro dams. How the Salmon avoided being dammed is a mystery. The twin dynamos of Bureau of Reclamation Director Floyd Dominy and Colorado’s water-working Congressman Wayne Aspinall would surely have wanted to dam the Salmon in two or three places. By some miracle of preservation, they never did. Guides on the main Salmon sometimes point out drill holes on the canyon walls where tests were made during what water historian Marc Reisner calls “the go-go years,” 1934-1976.

We saw a few ancient sturgeons and some dimpling trout, but no salmon in the Salmon. It seems to me that one of the goals of the 21st century should be restoring the salmon runs in the Salmon — or change its name to Sans Salmon River.

Woke Up, Fell Out of Bed, Dragged No Comb Across My Head

Summertime and the living is easy.

Out on the river, every day is different in all sorts of ways, but every day is the same, too. There are tents, but most of our guests have preferred just to throw their sleeping bags and thick sleeping pads on the beach sand.

We wake up. The crew has already made coffee, without which most of our guests would get a little edgy. One woman from out East, smart, thoughtful, is brewing her own French press coffee and giving small, highly valued, samples to other guests.

Some people pull down their tents right away, shake out their sleeping bags, stow away their personal gear, and bring their stuff down to the river. Others wait until they have had coffee and breakfast. It takes the crew a couple of hours to perform all the morning tasks, including the big one — packing everything back onto our five rafts.

The food is hearty, fresh and plenty.

The crew breaks camp. We clamor onto the rafts and down we go for 8-20 miles. There is plenty of white water and even more slack water, of course. We laze 0ur way down the river, sometimes chattering, noticing, commentating, remembering, but sometimes, for quite long periods, drifting in silence.

The weather is perfect: 85-90 degrees under the sun, but the river is perfect for swimming, and there are enough rapids to give everyone a thorough soaking a few times per day.

About 4 p.m. we find a good flat beach. Folks lug their tents and dry bags up to whatever sleeping site they have chosen. Pretty soon appetizers and wine are set out while the crew cooks dinner. We sit in camp chairs and recount the events of the day, other river trips, other vacations, other adventures.

Rinse and repeat.

We tumble over Class II rapids several dozen times per day, over Class III a couple of times per day, and Class IV just two or three times in five days. Nobody fell out. About half the people swam alongside the rafts for portions of the float. Part of the fun — given the change of river venues — is that none of the crew members have been over these rapids, either.

We saw river otters, deer, hawks, eagles, blue herons, a sturgeon or two, but the highlight was three bighorn sheep moments. In one, in a protected bay of the river, eight sheep stood perfectly still as in a tableau. In another, half a dozen kids trailed their mothers up what appeared to be 85-degree cliffs.

For almost everyone, the bighorn sightings will be one of the highlights of the trip.

Evenings, I talk about Jefferson, Thoreau, John Muir, Aldo Leopold, Edward Abbey. I’m interested in the paradoxes of western civilization: our capacity to crack the DNA code and land men on the moon, to perform heart transplants and to build replacement teeth with 3-D printers; and at the same time vaporize 65,000 citizens of Hiroshima instantaneously and so damage the biosphere that we cannot rule out mass extinctions of species, possibly our own. All praise to these lonely conservationists who have attempted to warn us that we must find ways to limit our ingenuity so that we don’t wind up destroying the world. All praise to Theodore Roosevelt for initiating the great conservation movement of the 20th century, and setting aside 230 million acres as National Park, National Monument, National Wildlife Refuge, National Forest (some of which we are gliding through), and National Game Preserve.

I suppose some of my fixation on this issue comes from a confluence. We are rafting a river that somehow escaped the industrial world’s obsession with turning the sublime into profit, and I had just seen the Hollywood film Oppenheimer three times in short order. Whether Oppenheimer’s “I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds,” will be the epitaph of Western civilization remains to be seen. Which precipices are we willing to back away from — to survive, to live more lightly on the planet, to forge a sustainable lifeway? Where will the wisdom come from at a time when the major religions have ceased to chasten human pride?

There is a limited appetite for discussions of this sort, particularly on a river adventure that is overwhelmingly delightful and relaxing.

The Rules of Rivers

Rivers are natural and inevitable metaphors. As Thoreau put it, “time is but a stream I go a fishing in.” The philosopher Heraclitus (ca. 540-480 BCE) famously said no one can step in the same river twice. It’s not the same river and you’re not the same person. In my experience, rivers are even better provocations for life meditation than campfires. Every day at some point I sit in the river feeling the tug of gravity pulling me toward the Pacific. The more you let yourself think about rivers, the more mysterious they become. A serious hydrologist can explain the hydrodynamics of a stream, but even s/he has to concede that some river actions are hard to explain, and that rivers seem at times to have what can only be called intentionality or even, if you are a mystic, something approaching consciousness.

Where Does All That Water Come From and Where Does It Go?

As with almost everything I encounter, I am mostly aware of my ignorance, or more precisely my ignorances. I can name a few stars and some constellations and can describe the Greek legends behind some, but I can’t really read the sky. What I know about geology could be contained in a passport book. I tried to explain river hydrology to myself as we glided along, but the truth is that I don’t really know very much, and I have little capacity to “read the river.” Rapids roar over rocks. I pledge, for the umpteenth time, before I return again, to master the star charts and penetrate the mystery of rivers. The best laid plans …

At some point during the trip, in our evening conversation circle, I recited Meriwether Lewis’ famous 31st birthday meditation, recorded on August 18, 1805.

“This day I completed my thirty first year, and conceived that I had in all human probability now existed about half the period which I am to remain in this Sublunary world. I reflected that I had as yet done but little, very little indeed, to further the hapiness of the human race, or to advance the information of the succeeding generation. I viewed with regret the many hours I have spent in indolence, and now soarly feel the want of that information which those hours would have given me had they been judiciously expended. but since they are past and cannot be recalled, I dash from me the gloomy thought and resolved in future, to redouble my exertions and at least indeavour to promote those two primary objects of human existance, by giving them the aid of that portion of talents which nature and fortune have bestoed on me; or in future, to live for mankind, as I have heretofore lived for myself.—”

After I recite this, I invariably comment that Lewis is being a little hard on himself. A few days earlier (August 12) he bestrode a feeder creek of “the mighty and heretofore deemed endless Missouri.” He has also made successful contact with the critically important (because horse rich) Shoshone. With any luck, he will reach the Pacific coast sometime later that fall. From almost any perspective, the expedition he commands has been a success. Only one man has died, probably of a ruptured appendix. The expedition is “go” for trans Rockies insertion.

We have nightly talks around the fire pit. Unfortunately, fires were prohibited this year, even in fire pans, and we were asked sternly by the sheriff’s deputies to extinguish the one fire we made, in ignorance of lower Salmon protocols. No great loss. I’d talk for a while about Lewis and Clark or about America’s long history of managing public lands, but soon the conversation would drift away from Lewis and Clark, and we’d find ourselves talking about America, about our national political and constitutional crisis, and eventually about Life.

Everyone who self-selected for the adventure had a story (and stories) to tell. It was a rich mix.

Channeling Our Inner John Wesley Powell

On the afternoon of the third to last day, we were working quickly down the river. It was time to camp. The problem was that with so many regular and refugee outfits on the river, good beaches were hard to secure. The crew member in the raft I was in didn’t see the signal to land in time. It was clear that we might well miss the landing site, in which case there could be no turning around and fighting the river. He pulled with all his might, his biceps bursting, but even with that heroic effort we slipped past the beach and headed into the rapids.

It was a scene right out of John Wesley Powell’s 1869 journey down the Green and Colorado rivers. Just 10 days into the 99-day journey, one of the four wooden boats, the No Name, missed a landing signal and was swept into the worst rapid (so far!). All three men on board were tossed into the Green River rapids. The boat struck a rock sideways and broke into two. Fully a third of the expedition’s provisions were lost. Major Powell looked on helplessly from the shore. The three exhausted and terrified crew members were rescued. As Powell assessed the damage, he briefly considered trying to walk out to Salt Lake City to resupply. What was rescued from the wreckage was redistributed in the other three boats and the sobered expedition members began their journey on the remaining 90% of the Green and Colorado canyons. Before long, the Powell expedition became a race against starvation.

In our infinitely safer journey on the lower Salmon, 154 years after Powell’s famous voyage, our crew members from the other rafts came running. Lines were thrown. Fortunately, we had run up against a large rock jutting out of the river. The raft was held up there, at least temporarily. After some strenuous tugging, mixed messaging, and cursing, we were pulled by yellow polyethylene ropes back up stream a dozen yards to the beach. Brendo, our river guide, was exhausted and a little abashed. If we had been swept through the rapids, the rest of the boats would have had to follow suit, as we had key equipment for the dinner, and it was important that we all stay together. That would have made for a tense evening downstream. We might have had to share a beach as disgraced refugees.

While this little drama was playing out, as in slow motion, I was drawn into my memory to Powell’s journey in 1869. They were in wooden dories. Because they were explorers, they had no idea what was around the next bend. None of Powell’s crew had ever run a rapid before. When the Colorado River proved too menacing, they portaged their baggage around the rapids or falls, and then lined the boats down with such river-weakened ropes as they still had in their possession. When the canyons hemmed them in, as was the case with us on this occasion, they had to climb high up on the rocks to piece out a portage route. Powell was one-armed. If we had had to do just that, scramble up 200 feet, crab-foot it over the rocks to a place above the beach, and then scramble back down, there would have been grumpy customers and plenty of chances to get hurt.

All’s well that ends well.

One evening around the inert fire pit, I talked about a book by Joseph Sax called Mountains Without Handrails: Reflections on the National Parks. The thesis of the book is simple enough. Humans deepen their experience when they limit their use of gross technology to achieve their ends. Thus someone who throws a grenade into a trout stream and kills 75 fish in an instant, is less a sportsman than the individual who has mastered fly fishing and pulls a gibbering trout out of a stream after hours of casting. Someone who kills an elephant with a bazooka is not sporting. Sax’s point is that we ennoble ourselves when we recognize that we must not simply surrender to industrialization. If we use all of our technological advantage, the poetry of life will be as deranged as the biosphere. When humans restrain their industrial mastery over nature, dignity is possible. So is spiritual awakening, spiritual growth. The couple in the canoe is more interesting to me than the six buddies in the jet boat hurtling upstream against the current, blaring music from onboard woofers against the cosmos, slugging beers the way Popeye eats a can of spinach. There is nothing poetic about a jet ski or a jetboat or an ATV on public lands. They just make noise.

We all understand the problem. Political paralysis in the national arena and in many of the states. A widespread feeling that the country is going down the wrong path, from both sides of the political spectrum. Runaway materialism. The waning of the humanities and civic engagement. The most dynamic nation in the world ruled by octogenarians. The consequences of a profoundly carbon-extraction economy have caught up with us. But we cannot quite see what life in a more sustainable system would be. We want to maintain the same lifestyle, the same easy access to all the fruits of life, with the hope of a techno-fix of our problems.

But, as Major Powell put it, “the river rolls on in quiet majesty.” And the stars are magnificent when I get up in the night to pee.

The Groover

Speaking of which, there are no bathrooms on the Salmon. Every outfitter brings along a crude, but efficient receptacle (often brightly colored) called The Groover. The only difference between The Groover and your toilet at home is that nothing gets flushed away. You do the math. Including the crew, a total of 30 people for six days, each person defecating once or twice a day into a receptacle no bigger than your home toilet bowl. That’s a steaming pile of poop. Given the accumulating bulk, the toilet paper is thin as tissue paper. A bottle of hand sanitizer possibly makes a difference, and there is a wash bucket down the hill, but nobody doubts that strict hygiene is an approximate science under such conditions.

The Lochsa River Compact

On the last day of the tour, we had a discussion in the morning about how America might choose to commemorate its 250th birthday: July 4, 2026. It was a rich discussion. Because we were people who had assembled from all over the United States, we all heard things we have not previously considered. After lunch, some people napped, others packed, but about 10 of us wound up siting on camp chairs in the Lochsa River. A few drank a beer or two, others, flavored water. At some point I was asked to explain my occasional river comment, “We’re doomed.” The question was whether it was just an Anglo way of saying oy vey or the Nordic uffda. In the space of 10 minutes, sitting knee deep in the fabulous upstream waters of the Columbia watershed, I laid out four or five deep problems the U.S. must at some point address: 1) the few and the many; 2) the costs of higher education, including the gargantuan mountain of student debt we have allowed to accumulate; 3) our incomplete national health care system; 4) immigration; 5) the loss of our national narrative; the persistence of racism. …

Then someone said, “Ok, we get it. We ARE doomed. But if you could choose one idea or program that might turn things around, what would it be?”

After a pause I said, National Service for all 18-year-olds, 18 months, or two years, away from one’s home community, living in dormitories, and a generous “GI Bill of Rights” as a reward for anyone who completes the program.

Suddenly, the river exploded into conversation. Suddenly, everyone was talking. We made a list of all the different ways you can define national service: VISTA, AmeriCorps, the Peace Corps, CCC camps, Red Cross, interning in inner city schools, border services, and the branches of the U.S. military. Nobody would be forced to carry a gun.

The enthusiasm was so great that we decided to form a Lochsa River Compact. Each of us would write to our Congress representative and our two Senators, to urge them to create a comprehensive National Service program as soon as possible. We could think of no better place to put the Archimedean lever that will lift the United States back to something closer to a republic. (It was not lost on us, of course, that we were mostly senior citizens planning years of service for people younger than our children.)

The idea for national service surfaces every few years, but never seems to reach a critical mass. Members of both political parties say they endorse the idea, but nothing ever comes of it. This is not 1934, they say. The unions oppose it, they say. It would be too costly, they say. Who is it who said, “men will sit around talking about the end of the world and never make an attempt to get up”?

Stay tuned. There is nothing original about our proposal, but the time is ripe for dramatic measures. It’s hard to concentrate on America’s great problems on a glorious white-water river trip, but traveling together in this way reminded all of us how privileged we are and how much might be lost if we don’t do whatever we can to turn things around.

OK, It Was My Dry Bag

The lost dry bag was mine. Thanks to the cooperation and the camaraderie of the river outfitters, the bag caught up with me on the second day. No harm no foul. Nobody could figure out how the bag was left behind at the put-in, but I have a hunch, and as Francis Bacon says, “Revenge is a dish best served cold.” Actually, I didn’t really care. I’ve been on 20-some journeys of this sort and in each case, no matter how little I put into the dry bag, it is more than I need or use. Our little river community rallied around me as we bedded down the first night. Lindy gave me a spare toothbrush, only slightly used. Another woman gave me a hoodie. One of the crew members lent me a spare sleeping bag. I recognized it as having been left behind by my old friend “Woody,” who has been on a dozen of my cultural tours and who, one summer, worked for Wayne’s outfitting business. I was on that trip. Woody turned out to be a double agent, slipping away from the crew kitchen to tell us insider stories about certain crew members, and then slipping back to the grill to say this year’s customers were a decidedly inferior lot! A double agent. He took me aside on the third day. I asked him how he liked sleeping out on the ground with no tent in the company of half a dozen 20-somethings. He loved it, he said, but he wasn’t sure what kind of funny cigarettes they were smoking after the guests had gone to sleep.

I was glad it was my dry bag that got delayed, not a guest’s. That might have been less agreeable. As I bedded down under the dubious materials that had been handed to me by crew and company, I realized that aside from my razor, my headlamp, and the book I was hoping to read (for four minutes per night before falling asleep exhausted), I did not really need anything that was not readily available to me. Plenty of food. The Groover. A raft to ride the waves. “A man is rich,” Thoreau wrote, “in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone.”

When I got my bag, I changed into Teva river shoes, and brushed my teeth more rigorously. By the end of the journey, there was one night when I was glad to have a proper sleeping bag.

And in the End …

Now I am back in “civilization” and life is taking its revenge for my short interlude off the grid. But when I close my eyes, I can hear the river cascading over the rocks near our camp. I can see the confluence of the Salmon and the Snake — one of the most beautiful places I have ever been, which I would not have seen had not the best laid plans of our trip changed one night at the champagne-soaked Sacajawea Hotel. My goal now is to keep the vistas and the impressions and the incidents and the meditations of the journey present in my mind through the year, without failing to be present at all the other adventures that beckon.