Day Four, Monday: Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, Cortez, Colorado.

This is the fifth in a series of dispatches from Clay Jenkinson chronicling his recent journey with two compatriots following the Colorado River and neighboring region. The day was spent at the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center. The two-week expedition explored the state of water, or the absence of it, in the West.

I took my shower this morning in a retro motel (aptly named the Retro Inn) with that small pink-tiled bathroom with the pink and reddish brown floor “treatment,” the toilet just a little too close to the wall, and the original tub shower. The clerk who checked us in told us proudly that the showers were excellent. When I stepped into the tub this morning, after adjusting the temperature, I turned the spigot to force the water up into the showerhead. What I expected was that small “misting” shower head that seems to supply two parts air for each part water, and you almost must jump around to get everything wet. I hate such showerheads, and I always leave my morning ablutions at such places a little grumpy. But no: what we have is one-foot-square rain showerheads! I was soon laved by a shower you might expect in a swanky New York hotel or in Paris. So, Cortez seems not particularly concerned about water conservation, at least not in the 1956 Elvis Room, with its painting of Marilyn Monroe at her most seductive, James Dean looking off the frame in existential alienation, and Elvis checking out Ms. Monroe’s legs.

When I open my door — yes, it’s a motel where you can drive up to your room! — I see snow on Dennis’ truck this morning, but the windshield is clear. He has been out in search of a better cup of coffee. Dennis has high standards for coffee. At the level of daily Grail Quest. He sometimes comes into my room to pick up a book or file and glares disdainfully at the Keurig rig placed there by the hotel. There are wine snobs. There are beer snobs (worse). There are cigar snobs (worst of all). And there are coffee snobs.

A Visit to the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center

We spent the whole day at the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center. The mission statement is lovely: “Crow Canyon’s mission is to empower present and future generations by making the human past accessible and relevant through archaeological research, experiential education, and American Indian knowledge.” We were there because Frank told us it would be the best way to prepare for the visits to Ute, Navajo, and Hopi communities over the next few days. He was right. I won’t say I’m not interested in archaeology, because that’s not true, but it is not one of the primary lenses through which I explore the American West. But our day with these gifted archaeologists, biologists, educators, and dendrochronologists was incredibly helpful and gratifying. Like all enlightened institutions these days, the Center has a land acknowledgement statement on its website:

The Crow Canyon Archaeological Center acknowledges the Pueblo, Ute, Diné (Navajo), Jicarilla Apache, and Paiute people on whose traditional homelands this institution sits.

Once we had met some of the staff, we were taken into a classroom, where Paul Ermigiotti told us about a Crow Canyon initiative being conducted with elder corn growers of the Hopi nation. Hopi men have been coming over the last few years to Cortez to plant corn in the traditional way using a digging stick called a sa’ya. Using heritage seed stock that may date back hundreds of years, the Hopi men plant kernels deep in the soil — eight to fifteen inches deep — to connect with the moisture there. The Hopi farmers are a long way from home in Cortez and yet they are able to “read” the land to know precisely where the corn should be planted.

After the harvest, Hopi women control the yield. The next spring, it is the women who select the seeds for planting. Everything depends on water, of course, but over the centuries the Hopi have mastered the growing of corn in arid country. The scale of their agriculture is modest. It yields subsistence. It enabled a steady state economy, but it did not in most years provide the kind of surpluses-for-market Euro-Americans regard as the meaning of agriculture or, better, agri-production. As the planet heats up and drought becomes the central story of the American West, could we learn from the Hopi and other practitioners of traditional subsistence agriculture? Certainly, but it would require a paradigm shift that white people seem unable to contemplate.

It was all fascinating and to me, at least, entirely new knowledge. Paul provided a briefing that prepared us for our encounter with a traditional Hopi farmer two days later.

After Lunch: Water, The West and Future of Civilization

After lunch we returned to the classroom and started to talk about the American West. There were nine or ten of us now, including Susan Ryan, the Stuart Struever Chair in Research as well as the executive vice president of the institute. She sat quietly in the back listening to all the talk. A recent University of Colorado Ph.D., Amorina Lee Martinez spoke passionately about our need to undergo a fundamental paradigm shift in the way we see nature, natural resources, the Colorado River, agriculture, and Native people. She was fortunate to study at CU under the great Patricia Limerick, whose book, Legacy of Conquest, rocked the world of western history when it was published in 1987. Our afternoon discussion was also graced by the presence of Craig Childs, the author of more than a dozen fine books about canyon country, including The Secret Knowledge of Water (2000), Apocalyptic Planet: Field Guide to the Future of the Earth (2012), and Grand Canyon: Time Below the Rim (1999). I know his work, but I had never met him. I felt fortunate to be in the room with such a writer and thinker. Like most great writers, he mostly listened to everyone else. And like most prolific writers, he said he was fighting several losing battles with deadlines.

Inevitably we talked about water. And the future. And John Wesley Powell. And the two great reservoirs. And the dams. And Native Americans. And Native American farming practices. And the future of civilization. And the meaning of life. You know, get a dozen over-educated readers and lovers of the West into the same room and the conversation will be essentially the same.

Although everyone in the discussion was a devoted professional doing work, they found gratifying and important, it turns out that the consensus was that civilization, or at least American civilization, is doomed. The great dams should never have been built. Well, certainly, Glen Canyon Dam should not have been built. Human generated global climate change was probably going to nip the whole species one of these days. In geologic time, it made no significant difference. Our civilization was fatally flawed by greed, corruption, materialism, colonialism, toxicity, toxic masculinity, and a few other problems. We were on a profoundly unsustainable path. We were soon going to hit the wall. Without a fundamental paradigm shift, we were going to break the planet’s capacity to support our species, at least as it is exhibited in the Euro-American consciousness. Maybe a few giant shocks to the system — 9-11, a global pandemic, mass violence every week now in America — would force us to change our ways. So far not.

I remember thinking, wow, this must be what it is to be an archaeologist. Every civilization they study is defunct. They sort through the garbage dumps (middens) of dead civilizations. The geology all around us, even thousands of feet thick with countless layers of sediment, cannot devote even a hundredth of an inch to the entire species run of homo sapiens. The geology is that deep. Time is that vast. The human way of counting time may work for a Tuesday appointment at the dentist, or remembering when the first atomic bomb was dropped, but it is essentially a worthless scale in the face of even a modest river canyon. You can almost see these archaeologists imagining the thousands of feet of sediment that will soon bury us like the mute clams and turtles that are petrified in ancient rocks. It’s hard to know whether their mantra is “eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow you shall die,” or “why bother, we’re ephemeral?” I’m seldom the most cheerful person in any room, but I half wanted to stand up and sing “God Bless the USA.” “We will blunder on, my friends, as humans tend to do!”

In short, we all worked ourselves into a funk. Edward Abbey and David Brower were right. We should have listened. But humans don’t listen. That’s why the Greeks invented the myth of Cassandra — the prophet who was always right but never once believed.

As we circled the drain of human optimism, finally director Ryan spoke for just one sentence. “We have to remember,” she said, “that humans are an invasive species — with tools.” Not to put too fine a point on it! What she said was both sadly true and immensely clever. I had never heard it before, but I guessed that this is a view held by others in science. Either that or this Ryan is a genius. Or both. Of course, to make sense of her koan, you must have a fairly long conversation about what constitutes an invasive species, but it is certainly true that humans have carried their DNA to every continent, nation, every state, every country, every township, every square foot of the planet and set up housekeeping in some really inhospitable places. I live in one of them. North Dakota. And oh how Frank makes that his punching bag!

“We have to remember that humans are an invasive species — with tools.”

Susan Ryan, Crow Canyon Archaeological Center

It’s a great joy to be with a group of people so committed to figuring things out, getting things right, listening to the land, paying daily respect to the people who have lived on these landscapes for millennia. We are all so beleaguered by what passes for our national discourse — who’s hired or fired in major media, whether the current President is demented and the former one deranged, whether the nation’s descent into mass violence will peak and begin to fade or just take us deeper into Dante’s Inferno — that we sometimes forget how many tens of thousands of extraordinary people are quietly and without fanfare doing extraordinary things throughout this vast country. It’s heartwarming and a little heartbreaking to witness so much good faith and integrity as we found among the unsung staff of the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, and to realize, again, that this, too, is America. In fact, this must surely be a better representation of America than the poison blather on nightly cable.

We could have spent several days with them. They were the perfect beginning to everything that followed over the next week.

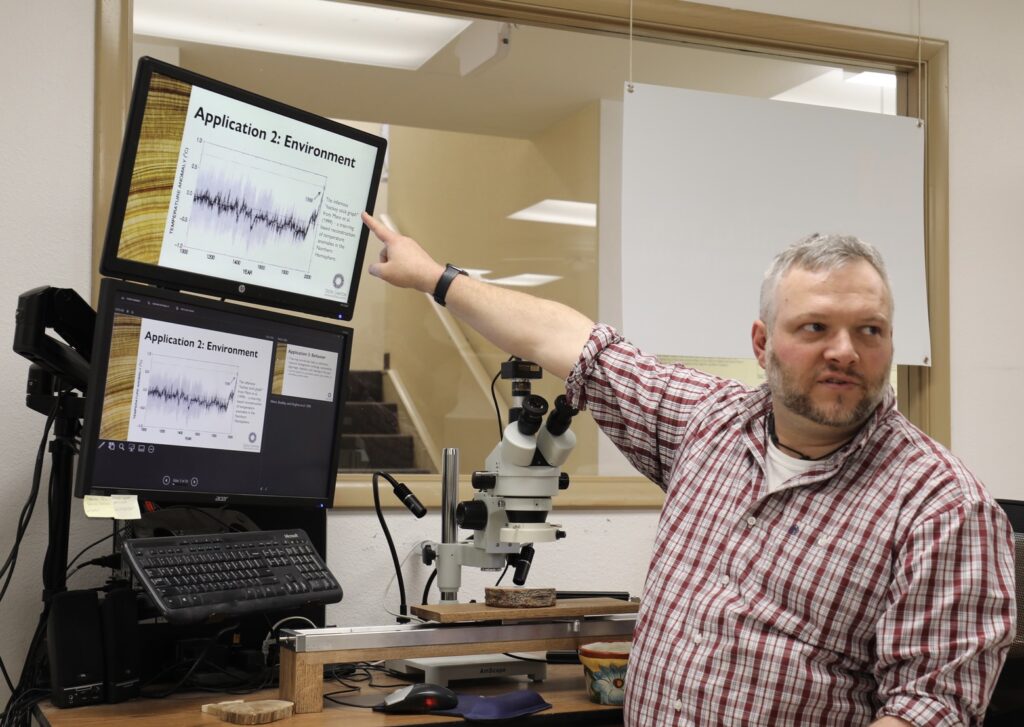

The conversation broke up and we got a tour of the labs and storage rooms in the basement of the center. The house dendrochronologist Ben Bellorado showed us a microscope that blows tree rings up to the size of a hoola hoop. He showed us a ring of a very old tree that indicated an early frost on the plateau. I wanted to learn so much more from him so I set up a Zoom interview for after my return to North Dakota.

We said our goodbyes, regrouped at our retro motel, and then went to dinner at a restaurant where Frank’s fourth cousin twice removed, who was briefly married to John Wayne’s stepdaughter, shot a movie in 1948, with Frank’s college roommate as the chief cinematographer. Or something like that. I may be wrong in one or two details, but I am pretty close. I think Gandhi was in the mix somewhere. Or was it Tom Mix? I pre-ordered a couple of rounds of drinks. By the time we pushed our chairs back from the table, we had each confessed that we think human civilization is on the whole a good thing and it has a chance to survive.

Editor’s Note: You can track Clay’s dispatches on this Colorado River Journey by following the links from his route and itinerary below. You can also keep up with all LTA’s dispatches, essays, photos, and podcasts on this topic through the tab “Water in the West.” This is one of many ongoing road trips at the heart of Listening to America. Our mission is to “light out for the territories,” traveling less visited byways and taking time to see this immense, extraordinary country with fresh eyes while listening to the many voices of America’s past, present, and future.

Water in the West — Routes and Itinerary

- Introduction: A Colorado River Journey, The Trek Begins.

- Day One, Friday: I-70 Vail to Green River; Utah 24 to Torrey; Utah 12 to Boulder, Utah.

- Day Two, Saturday: Boulder, Utah.

- Day Three, Sunday: Utah 12 to Torrey; Utah 24 to Hanksville; Utah 95 to Natural Bridges National Monument; Utah 261 to Mexican Hat; U.S. 163 to Bluff; Utah 162 to Aneth; Indian Route 5068/Arizona County Road G to Cortez.

- Day Four, Monday: Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, Cortez, Colorado.

- Day Five, Tuesday: Colorado 160/491 to Chimney Rock; Colorado 160 to Teec Nos Pos; Colorado 160 to Mexican Water; U.S. 191 Tsaile; Arizona 64 to Chinle.

- Day Six, Wednesday: Canyon de Chelly; U.S. 191 to Burnside; Arizona 264 to Second Mesa.

- Day Seven, Thursday: Hopi Cultural Center; Arizona 264 to Tuba City; U.S. 160 to U.S. 89; U.S. 89 to Bitter Springs; U.S. 89A to Marble Canyon.

- Day Eight, Friday: U.S. 89A to Bitter Springs; U.S. 89 to Page, Arizona.

- Day Nine, Saturday: Lake Powell; U.S. 89 to Kanab.

- Days 10 & 11, Sunday/Monday: U.S. 89 to Utah 20; Utah 20 to I-15; I-15 to Salt Lake City.

- Days 12 & 13, Tuesday/Wednesday: Salt Lake City.

- Reflections on A Colorado River Journey.