Marc Reisner’s Cadillac Desert has been around for a long time — since 1986 — but it continues to be the best introduction to the subject of Water in the West. Reisner (1948-2000) should be alive today to help us piece our way through the profound water crisis still developing in the American West. Just at the time when the country was beginning to consider decommissioning some of its dams, particularly those that have decimated the salmon runs in the Columbia River Basin, we now hear talk of building new dams and finding a way to pipe water from the Columbia (or beyond) to the American Southwest.

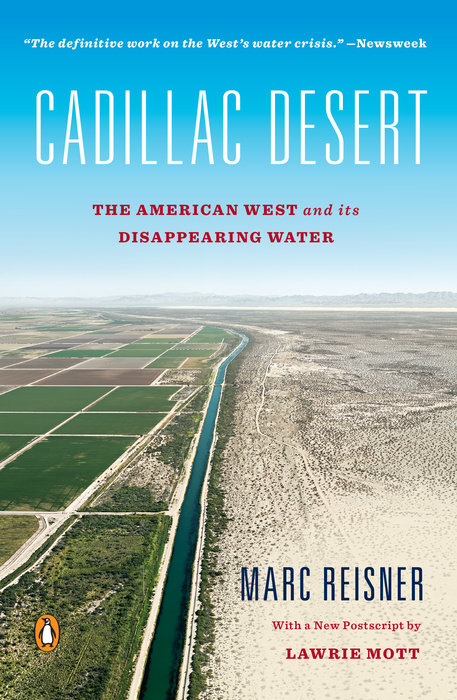

Cadillac Desert explores the water issues on the Colorado River, the Columbia, the Platte, the Snake, and the Missouri, but the best of this book is about California — the Owens Valley, diversions of the Colorado River, the incredibly complex hydrological infrastructure of the most populated state, and the sixth largest economy in the world. Reisner also devotes a superb chapter to the Ogallala Aquifer, a lake the size of Lake Huron that underlies the Texas Panhandle, western Kansas and Nebraska, plus the eastern edge of Colorado and Wyoming.

When I read a book that I depend on to make me better informed (as opposed to a novel by Charles Dickens, for example), I read first the chapter about something I already know well. In this case, it’s the Missouri River. I live not more than two miles east of it in Bismarck, N.D. I’m a Lewis and Clark scholar and editor. For more than 20 years I have led a cultural tour on the White Cliffs section of the Missouri southeast of Fort Benton, Montana. I have read the Missouri River literature, including Stanley Vestal’s classic for the Rivers of America series, The Missouri (1945).

Here’s my report. Reisner is not only spot-on about the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Sacagawea is not a guide), but he writes movingly about the holocaust that the building of Garrison Dam became for the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara, who were not consulted before the best river bottomlands (more than 150,000 acres) on which their economy depended were inundated. Reisner rightly reports that the dam was re-engineered (lowered 20 feet) to prevent the reservoir from having any negative impact on the white city of Williston, N.D., population ca. 7,000 then, but the Corps of Engineers summarily refused to relocate the dam to protect reservation lands. “Virtually every productive acre of bottomland the tribe owned would go under” he writes. Reisner tells the heartbreaking story of the tribal business council chairman, George Gillette, bursting into tears in Washington, D.C., on May 20, 1948, when the pathetic compensation agreement was signed. “Right now,” he said, “the future does not look good to us.”

Whether Reisner’s conclusion that “The Fort Berthold Indians [Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara] have never recovered from the trauma they underwent,” needs some revision (under consultation with the MHA Nation itself) is unclear, but Garrison Dam has rightly been called “the greatest crime against American Indians of the twentieth century.”

The Missouri River is not the heart of this excellent book, however. California is the true “Cadillac desert.” Because Reisner is such a good writer — clear, jargon-free, on focus, often witty, occasionally sardonic — it is a pleasure to read the “Chinatown” story of LA’s theft of the water of the Owens River on the east slope of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. He’s outstanding on the heroic industrial efforts it took to create an irrigation empire in a Southern California desert that became known as the Imperial Valley after its ca. four inches of rain per year were pieced out with the industrial delivery of millions of acre feet of the Colorado River. Reisner has less to say about the Columbia River, which has been brilliantly analyzed by Blaine Harden’s A River Lost: The Life and Death of the Columbia.

The Ogallala Aquifer

I have a particular interest in the Ogallala Aquifer, since I lived on top of it in northwestern Kansas for a time, and my in-laws (of the time) were pioneer irrigators with nine miles of underground pipe. I did some pipe hauling on blistering summer days, when the 8-inch by 20-foot aluminum pipes were not only scorching but quarter-filled with sand brought up by the massive pumps.

Reinser’s account of the discovery, tapping, and sprinkling of that vast body of water over the High Plains is one of the best things in the book. The Ogallala makes 112 million acres of semi-arid grass country “bloom,” as the nation’s irrigation boosters described it at the end of the nineteenth century. Unfortunately, the Ogallala does not recharge. It is fossil water. When it’s gone, it’s going to be gone. Already irrigation farms up and down the region have “gone dry” because there is either not enough water left in the Ogallala there or it is now too expensive to pump up to the surface. As with all such entities, institutions, and habits in America, reform is coming but at such a glacial pace that things are likely to move into a crisis mode. Jefferson was so right. If humans don’t proactively reform their world, the change will come anyway but only in the wake of disaster. I have a brother-in-law out there who is doing all the right things to conserve what he has. He has shut down several fields, installed state-of-the-art drop nozzles in his center pivot systems, planted crops that need less water, rethought the cash flow of his farm.

Reisner’s pen portraits of important men (all men) in the hydroelectric industrialization of the West are superb. I particularly respect his biographical treatments of John Wesley Powell, Floyd Dominy, William Mulholland, David Brower, Wayne Aspinall, and Mike Straus. He gets a little personal with Dominy, who is clearly the villain for most conservationists’ narrative of the damming of western rivers.

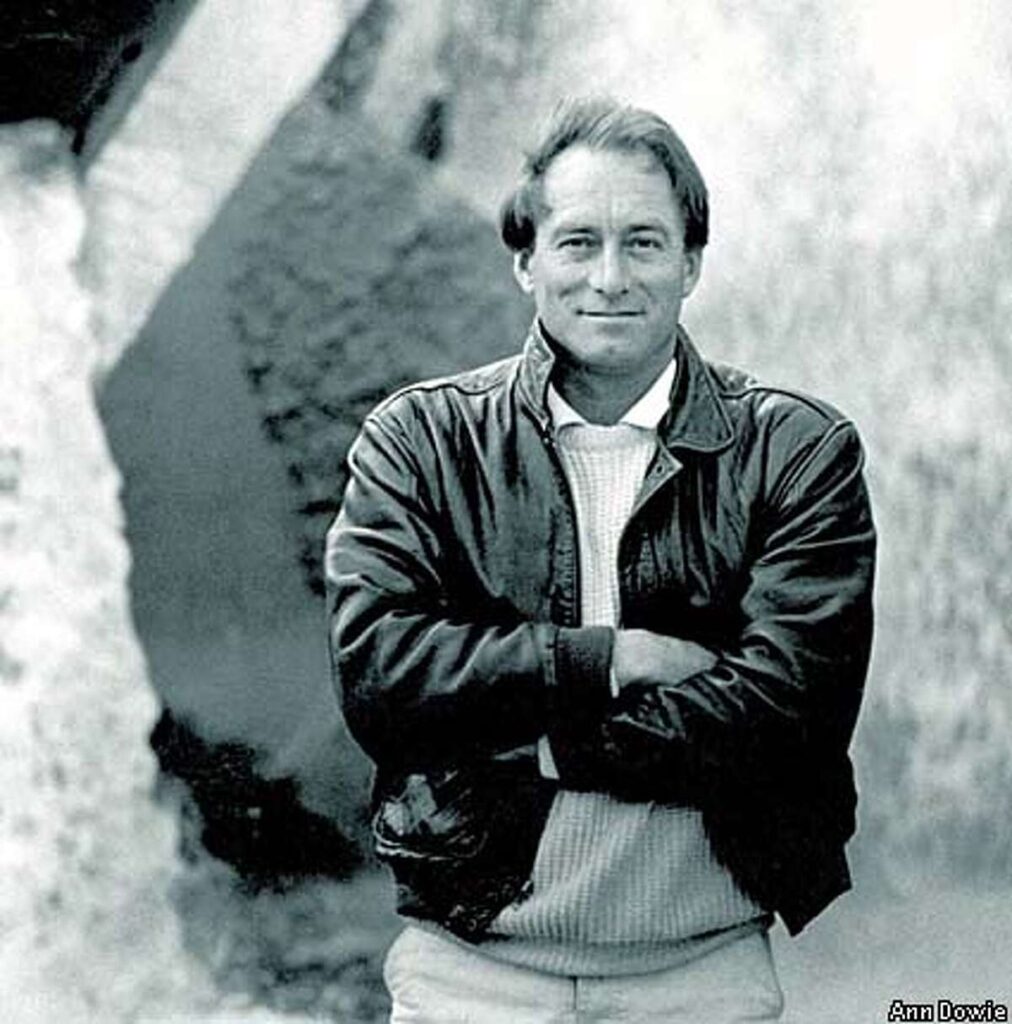

Reisner was handsome, soft spoken, suave when he made his public appearances. He had a ready sense of humor, and it was easier to hear the sarcasms and the ironies when he spoke than when we only had the book before us.

Cadillac Desert is where you must start if you want to understand Water in the West. The Revised Edition has an excellent afterward by Lawrie Mott, a former staff member of the Natural Resources Defense Council. She brings things up to date. It would be an understatement to say that a lot has happened since Cadillac Desert was published in 1988.

And yet the paradox and tragedy of the American West is that so little has happened.

Coda

I just reread Reisner’s final chapter, “A Civilization if You Can Keep It.” It’s tremendous.

He quotes Floyd Dominy testifying before Congress, and lets Dominy ask, “Could one imagine what the West would be like if there hadn’t been a Bureau of Reclamation? If the rivers hadn’t been turned out of their beds and allowed to remake that pitiless landscape?”

Reisner generously writes, “It is a question worth thinking about,” and then reminds us that much of the West would be like Nevada with its myriad of ghost towns and just a handful of places where people actually live.”

Later in the chapter Reisner writes, “The government — the Bureau and the Corps of Engineers — first created a miraculous abundance of water, then sold it so cheaply that the mirage filled the horizon.”

The miracle of western industrial water development, Reisner writes, has been “amazingly fruitful in the short run [but] leaves everyone and everything more vulnerable in the end.” After my two weeks on the Colorado Plateau, I can report that that is how everyone feels (at different levels of anxiety).