Introduction, The Trek Begins.

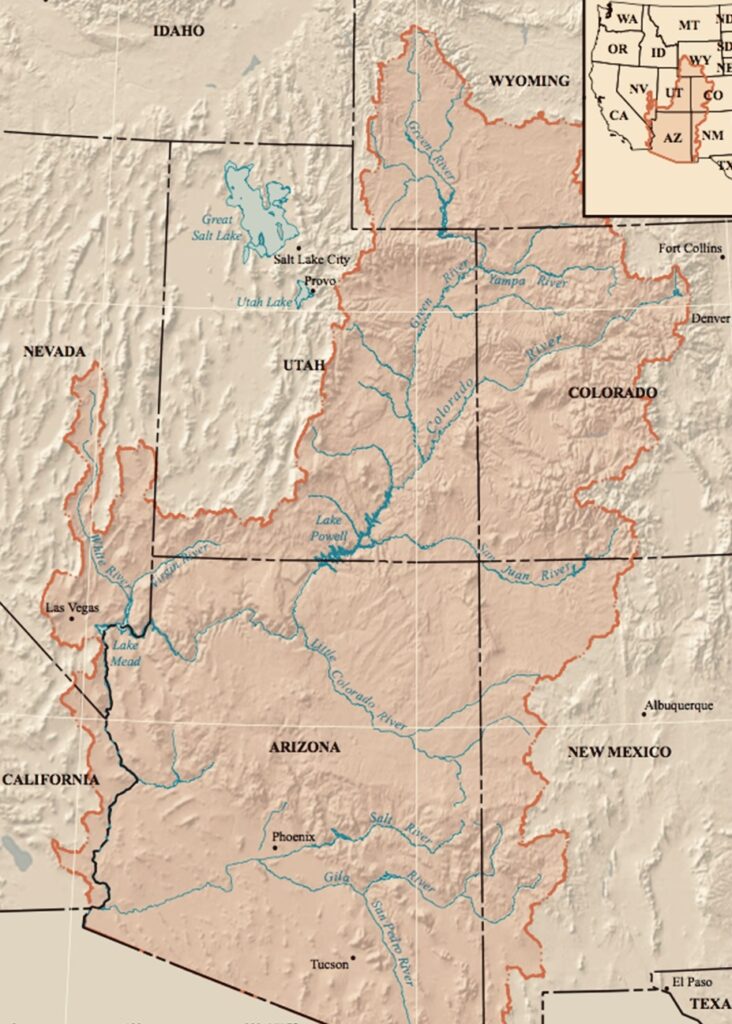

This is the first in a series of about a dozen dispatches from Clay Jenkinson we’ll publish over the next several weeks chronicling his recent journey following the Colorado River and neighboring region. Clay’s two-week road trip with two traveling companions began in Vail, Colorado, as an unusually snowy winter lingered into spring. Their route tracked the meandering river through plateau country, eventually reaching Kanab, Utah. It crossed territory that had remained essentially unmapped until John Wesley Powell led a crew down the Green and Colorado Rivers in four wooden dories in 1869. After Kanab, they took a final jog north to visit conditions at the Great Salt Lake. The journey aimed to explore the state of water, or the absence of it, in the West. This expedition is one of many ongoing road trips at the heart of Listening to America. Our mission is to “light out for the territories,” traveling less visited byways and taking time to see this immense, extraordinary country with fresh eyes while listening to the many voices of America’s past, present, and future. You can follow Clay’s journey, his dispatches, essays, photos, and podcasts on this topic through the tab “Water in the West.”

“To grasp the meaning of it all we require a science with room for more than data and information, a science that includes sympathy for the object under study, and more than sympathy, love.”

Edward Abbey

Altogether we traveled 1,620 miles and we barely made a dent in canyon country, hardly even a dent in Utah. Our rig was a gray Ford 150 super cab pickup. Dennis and Frank sat in front. I delivered up snacks from the back seat, including a careful rationing of outstanding chocolate chip cookies provided by Frank’s wife Georgie.

Dennis, now retired from a successful career as the CEO of a publishing and research company, lives in the shadow of the Aquarius Plateau in southern Utah. He’s in charge. Frank is a mapmaker, former park ranger, tour operator, and now owner and chief dishwasher of a food truck in nearby Escalante, Utah. He claims he knows everyone west of the Mississippi, and apparently he does. He’s our chief scout. I’m the humanities scholar and writer, or what is derisively called “the talent” by those in front. In the media world, “the talent” is never a term of respect. That’s why I am opening bags of chips with my teeth and putting together salami and cheese sandwiches for the boys up front, using my AAA credit card for a cheese knife.

As we moved purposefully but without urgency from one place to the next in southern Utah, western Colorado, and a bit of Arizona and New Mexico, we saw dozens, even scores of side roads we would have liked to explore. To find out where they went and what they revealed. We stopped to take photographs a few times per hour, eight or nine times per day. The rule was, any one of the three of us could call an unscheduled pee break, a coffee break, or a photo stop.

We were wandering with purpose to study the water situation in the American West. Our mission was a little more refined than that, not much. We came in believing that the West was in a grave water crisis and what we are told to believe will be a permanent water crisis. Three factors, perhaps related, have contributed to the crisis. First, the Colorado River system is over-allocated. So much water has to be drawn out of the system each year now, regardless of the snowpack or the annual flow, that even in “normal times” there is not quite enough river to go around. In other words, the two great reservoirs are down because we are drawing too much water out of them. Second, we’re in a sustained drought. There is some talk of a 1,200-year drought. I automatically reject that number as exaggerated (at least unverifiable), but everyone we meet agrees that it is a very prolonged drought. Flows have been mostly below average for the past 20 years. In other words, however high or low the reservoirs are, the watershed is not feeding it enough water to handle all the existing allocations. Third, we must factor in whatever it is we mean by global climate change: not just below-average flows but changes in the mountain environments — evaporation without melting, premature rains, etc. — that will impair the flows in new ways. Needless to say, as the temperature in the Southwest rises, surface evaporation in the great reservoirs will increase.

As we began our near two-week journey at the end of March 2023, we were aware that the 2022-23 winter has bestowed one of the great snowpacks all across the trans-Missouri West. That will certainly change the story later this summer when Lake Powell is expected to rise by perhaps as many as 70 feet and Lake Mead by perhaps 23-30 feet. Thus, we are pinioned in a paradox. The story “feels” like it is one of potentially catastrophic drought coupled with the necessity of a paradigm shift about how we manage the Colorado River. But it is at least possible that the drought is now ending or that we may have a run or two or three unusually wet winters within a generally worsening drought. We don’t know. Among the people we meet (a dozen or more per day) even the most optimistic speak of this summer’s rise in the reservoir levels with a kind of sheepish caution. They want to feel wildly optimistic, but they have been chastened by the dramatics of the last few years. Everyone says the big winter will help, but not enough to end the crisis.

We could spend the full year studying this subject and even at that we would be ignoring many important “tributary” stories that would help us understand the vastness, variability, and complexity of the Water and the West theme. So, we have to choose. At least we have to choose which places we want to visit now, which individuals we can really only interview in person, on location, in place.

We wanted to get beyond the apocalyptic trope and the bathtub ring. That’s where this story is stuck in national media and the minds of most Americans. We wanted to see this issue from a Native American perspective. We wanted to meet indigenous people and listen hard. We wanted to bring a historical perspective to our travels (that’s where I come in) and an archaeological perspective. For that we would spend a day at the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center in Cortez, Colorado. We wanted to get off the beaten path, wherever that was possible. We wanted to explore. We wanted to listen to a wide range of voices. We wanted to drink in the beauty of canyon country. We were going to need more homemade cookies.

What we discovered on this journey — to jump ahead for the purposes of clarity — was that the story is more complicated than we had expected. The two great reservoirs may be unprecedentedly low, but there is still a helluva lot of water in them both, as our Lake Powell boat captain Randy Reed told us several times in several ways. We learned, too, that Lake Powell — even at 175 feet down, with stranded marinas and all that bathtub ring — is still astonishingly beautiful. It’s even beautiful in new ways made possible by the dramatic drop in the lake level. It’s tempting to say Lake Powell is unique on Earth. Third, we learned that the southern Utah and northern Arizona economy is not as dependent on Lake Powell recreation as we would have thought. Our Page, Arizona, host Brady Budd explained that Page is at the center of the great circle route featuring the Grand Canyon, several National Parks, a nearly infinite pair of National Monuments, the Navajo and Hopi nations, and Lake Powell, which still contains “a helluva lot of water” (hereafter HLW). We learned that many Native Americans feel the satisfaction of continuing to practice dryland corn agriculture in a way that produces results even in a time of unusual aridity.

The beauty of the landscape of southern Utah is staggering. You can if you wish, gravitate to the designated National Parks and within them to the photo op and “scenic view” signs. Utah has the third largest number of national parks at five. California (of course) has nine and Alaska eight. But Utah has the second largest National Park and monument acreage (after Alaska). Impressive. But what is astonishing is how many landscapes there are in every direction seemingly forever that would be national parks in any other state. The question — aside from sagebrush politics — is what does not qualify for National Park status on the Colorado Plateau.

For example, I discovered the Henry Mountains on this journey. I suppose I have seen them before from some long distance, and I knew they were named, by members of the second Powell expedition in canyon country, for Joseph Henry, the first director of the Smithsonian. But that was all I knew. On this journey I saw them from almost every angle and from a wide range of distances. They were covered with snow in the way you would more likely associate with Mount Shasta than the Colorado Plateau. If they were relocated somewhere less dramatic — say Nebraska — they would be the number one scenic destination in the state. They are the pyramidal remnants of a giant laccolith that pressed up from below like a bubble or blister millions of years ago.

The names of the Henry Mountains are all of historical interest to us. The second Powell expedition (1870-71) passed through the Henries, which Powell’s brother-in-law Almon Thompson first called the Dirty Devil Mountains. Mount Ellen (the highest at 11,522 feet) is named for the Thompson’s wife. John Karl Hillers (Mount Hillers) was the photographer of the second Powell Expedition (1870-71). He lugged his 1,000+ pound camera gear up and down the canyon walls. Mount Holmes is named for William Henry Holmes, an artistic genius, whose stratigraphic illustrations of canyon country, including the Grand Canyon, are almost unbelievably beautiful. Mount Pennell is named for Joseph Pennell, an illustrator Almon Thompson admired but who was not on either of the Powell expeditions.

Our intrepid guide, scout, and adviser Frank informed us that the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) maintains a herd of approximately 350 bison along the lower slopes of the Henrys. Who knew? The Henry Mountains Bison Herd is one of only three free-roaming buffalo herds in America (along with Yellowstone and Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota). I made a note to come back to the Henrys to camp, hike, and (if possible) observe those free bison. What you learn on a trip like this is how little you know even about things you thought you knew pretty well. You learn how much America there is to explore, and how much more there is than you reckon from your easy chair back home. Every time we hurtled past a promising side road we felt a little sad. You learn that Steinbeck was right: it is a “monster country,” and no person can get to know much of it even in a lifetime of wandering and reading.

The Henries — or the Vermillion Cliffs or the Lukachukai Mountains or the lower Paria canyon or Navajo Mountain or the Book Cliffs or Zion or Bryce or Canyonlands or Cedar Mesa or Antelope Canyon or Grand Staircase Escalante…. It’s paradise in every direction. Every journey of this sort needs to be regarded as a menu, a series of aching invitations for return journeys and new itineraries. As I say, we are going to need more cookies.

Fill in the blank: if there were only one state it would have to be _____. Utah is always in the top three. Short list: Montana, Colorado, Utah, California, Washington. Or perhaps it is as one of my professors once said when I asked him which novel by Charles Dickens he liked best: “I suppose it depends on the one you have most recently read.” Wherever you go in southern Utah, it feels as if you might still be in a National Park.

The only downside of southern Utah is that the towns all seem a bit forlorn. There are some superb local restaurants scattered here and there, but there is a dusty, windswept, low-amenity feel to most of the towns, as if they were, like Page, thrown up for a temporary industrial purpose (the building of Glen Canyon Dam) and then eventually insulation was added to the houses for the long run.

So on we drove.

Editor’s Note: You can track Clay’s dispatches on this Colorado River Journey by following the links from his route and itinerary below. You can also keep up with all LTA’s dispatches, essays, photos, and podcasts on this topic through the tab “Water in the West.” This is one of many ongoing road trips at the heart of Listening to America. Our mission is to “light out for the territories,” traveling less visited byways and taking time to see this immense, extraordinary country with fresh eyes while listening to the many voices of America’s past, present, and future.

Water in the West — Routes and Itinerary

- Introduction: A Colorado River Journey, The Trek Begins.

- Day One, Friday: I-70 Vail to Green River; Utah 24 to Torrey; Utah 12 to Boulder, Utah.

- Day Two, Saturday: Boulder, Utah.

- Day Three, Sunday: Utah 12 to Torrey; Utah 24 to Hanksville; Utah 95 to Natural Bridges National Monument; Utah 261 to Mexican Hat; U.S. 163 to Bluff; Utah 162 to Aneth; Indian Route 5068/Arizona County Road G to Cortez.

- Day Four, Monday: Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, Cortez, Colorado.

- Day Five, Tuesday: Colorado 160/491 to Chimney Rock; Colorado 160 to Teec Nos Pos; Colorado 160 to Mexican Water; U.S. 191 Tsaile; Arizona 64 to Chinle.

- Day Six, Wednesday: Canyon de Chelly; U.S. 191 to Burnside; Arizona 264 to Second Mesa.

- Day Seven, Thursday: Hopi Cultural Center; Arizona 264 to Tuba City; U.S. 160 to U.S. 89; U.S. 89 to Bitter Springs; U.S. 89A to Marble Canyon.

- Day Eight, Friday: U.S. 89A to Bitter Springs; U.S. 89 to Page, Arizona.

- Day Nine, Saturday: Lake Powell; U.S. 89 to Kanab.

- Days 10 & 11, Sunday/Monday: U.S. 89 to Utah 20; Utah 20 to I-15; I-15 to Salt Lake City.

- Days 12 & 13, Tuesday/Wednesday: Salt Lake City.

- Reflections on A Colorado River Journey.