The open road: liberation and costs of the privately owned car.

Afoot and light-hearted I take to the open road,

From Song of the Open Road, Walt Whitman

Healthy, free, the world before me,

The long brown path before me leading wherever I choose.

There is nothing I like more than driving the American West winter or summer on secondary roads through immense and largely empty landscapes with no fretful deadline and no pre-chosen destination for the night. I like to be able to stop (or divert) whenever I see something I want to explore. On an average day of desultory exploring, I may stop at a dozen roadside historical markers, several dozen landscapes I wish to photograph, a wee bookstore in an unlikely town, a local museum, a combination coffee shop, tanning booth, and barbershop, or a hiking trail that looks appealing. At night, after securing a room in a Western town of 4-6,000 people, I like to find the steakhouse out on the edge of town for a beer and a burger or a burrito.

I have always felt exceedingly privileged to be able to get into a $25,000, 3,289-pound personal metal transportation machine and drive a thousand miles (or 10,000) without ever encountering a border patrol; and — except on freeways — being able to stop by the side of the road almost anywhere, including on the most remote gravel roads, knowing that the chance the car will break down now approaches zero. I’ve changed approximately 20 tires during my life. I’ve run out of gas half a dozen times, but virtually always from inattention and heedlessness, not from the distance between gas pumps. America makes automobile life easy and — if you do the math — surprisingly inexpensive.

We take all this for granted as part of the American Way, part of the package of unlimited American freedom. We should not. I am aware that the solo auto journey is probably unsustainable in the long run, and for all of my intellectual awareness of the sequential problems of the ozone layer depletion, acid rain, domestic and global distributive justice inequities, periodic Arab resistance against America’s sense of carbon entitlement, and now global warming and climate change, I do hope the window of such freedom and privilege stays open (hopefully in some greener way) and that I will be able to “drive out” my life in the American outback.

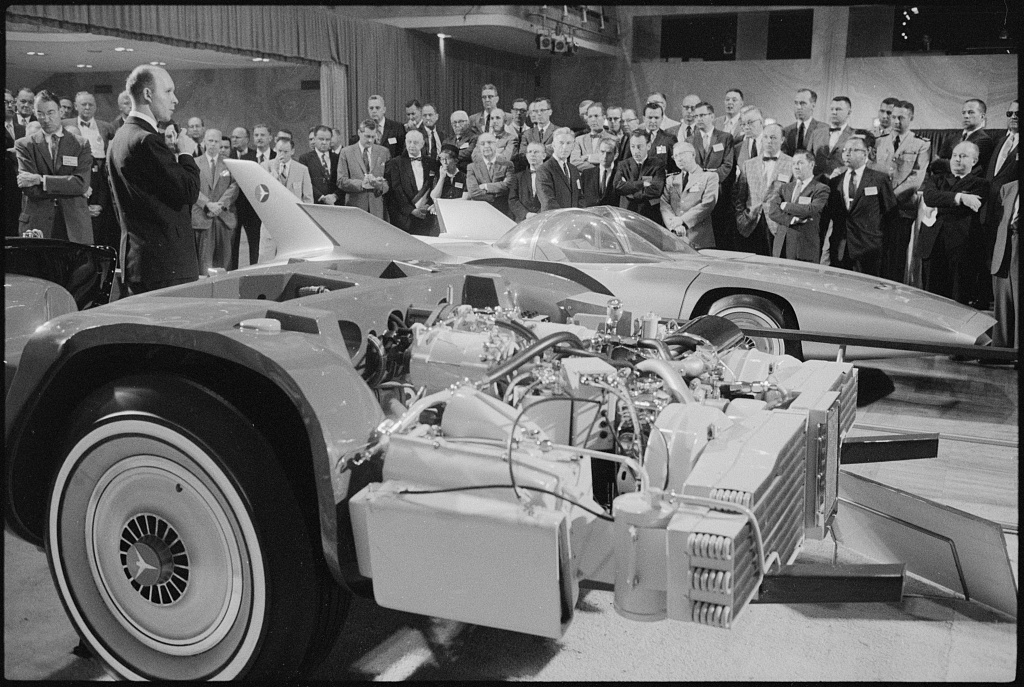

The Miracle of the American Automobile

Think about the American automobile. It has been one of the most revolutionary (and liberating) of technologies in human history. When Theodore Roosevelt became the first president to make a campaign tour in an automobile in 1902, the American people were still getting around, if they ever ventured more than 25 miles from home, on the national network of railroads, with horses and buggies — and the strength of their feet for shorter distances. Only half a century later, we had to build a colossal national highway system to accommodate America’s profound love affair with the automobile. The Interstate system cost $680 billion in today’s dollars. As a conduit for freight hauling, it has paid for itself a hundred times.

Americans love their cars so much that they eat in them, buy liquor at drive through facilities, attend church services in them (think of the Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove, CA), have sex in their back seats, view the corpses of their dead friends and relatives in drive-through funeral parlors, vote in them, get their Covid vaccinations in them, consume drink and drugs in them, sleep in them, and — increasingly — live in them.

As of 2022, there were 290.8 million cars in the United States (with a population of 340 million). When we need a quart of milk or a carton of cigarettes, most of us drive rather than walk a quarter of a mile to the nearest convenience store. More than 70% of Americans commute to work by automobile, usually alone. The privately owned car is as central to the American way of life as television and the cell phone and most of us have no idea how we would be able to live without it.

We Americans regard all of this as a kind of national birthright, but we are the only people on Earth who get to live this way. Our joyful addiction to automobiles didn’t just happen and how we live now is almost certainly not sustainable. Societies make choices. Americans determined to feed their automobile addiction no matter what the cost to the nation’s railroads, the cost to town centers and the viability of local shopping, and the cost of rootlessness of suburban and exurban existence. Not to mention the “cost” of America’s foreign policy, which has had to be subordinated to the uninterrupted flow of Middle Eastern oil.

Talk about American exceptionalism. Americans have some of the lowest gasoline prices in the world. A gallon of gas costs about $7.33 in Germany, $7.14 in Italy, and $8 in Great Britain. That’s more than three times the cost of gasoline in the United States (about three dollars per gallon on average). In Canada the average price of gas is about $5.10 per gallon.

The two cars I grew up with were both owned by my parents. One was a 1964 Ford Falcon. It averaged 14.6 miles per gallon. The other was a 1968 Chrysler New Yorker with the big 454 cubic inch engine. It averaged just under nine miles per gallon. When I was a high school student gas cost about 35 cents per gallon. On a Friday night in my hometown of 13,000 people, my best friend and I would put a dollar of gas in the car and cruise the four-mile Main Street a dozen or 20 times in hope of encountering some Playboy models who happened to be exploring small towns in the American heartland. Our success was not as great as we fantasized, and we generally ended up at about 9:30 at the A&W Root Beer Stand on the eastern edge of town.

If you calculate inflation and the cost of living, a gallon of gas that cost 35 cents in 1965 would cost about $3.25 today. The current (early 2024) national gas price averages $2.86 per gallon. The federal per gallon gas tax in 1965 was four cents per gallon. It is now about 23 cents per gallon. That means that the cost of a gallon of gas today is less (adjusted for inflation) than when I was a feckless adolescent! Back then a can of Coke cost 10 cents. A candy bar cost between five and 10 cents. A gallon of milk cost $1.05, a dozen eggs 53 cents, a loaf of bread 20 cents.

If you factor in the dramatic improvements in fuel efficiency in the last five decades, the cost of getting around is even cheaper now than the price per gallon suggests. My three recent cars (last 15 years) on average have gotten 25-35 miles per gallon. Let’s say 30 mpg. That means I get twice as many miles per gallon now than I got in that Ford Falcon and three times more than in the huge Chrysler New Yorker.

We did not know about our “carbon footprint” back then, but we had air pollution, especially before the advent of unleaded gas, which many of my fellow heartlanders denounced as likely to lower the available horsepower of our big Detroit cars. The first time I heard the word pollution was in the late 60s on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, and his focus was on New York and then Los Angeles. Out here in the heartland where the wind blows, we shrugged at talk of air pollution. Now when I drive long distances alone for not urgent purposes I experience waves of concern, even guilt, for my outsized carbon footprint. This is just one small window on the Paradox of America. I know the planet could not take it if all eight billion of us lived this way. If we allow ourselves to think about it, which we work hard not to do, we Americans realize that we only get to live the way we do (from conspicuous consumption to diet to food waste to energy consumption, etc.) because we are the world’s hegemon and we don’t really believe that the rest of the people of the planet deserve to live as comfortably and opulently as we do.

As Val Kilmer’s Doc Holliday says in Tombstone, “Wyatt, my hypocrisy knows no bounds.”

I know I panicked when James Kuntsler published The Long Emergency: Surviving the Converging Catastrophes of the Twenty-First Century in 2005. In fact, that was what inspired me to move from Reno, Nevada, back to my homeland in North Dakota. This was before fracking, which has changed everything. Kuntsler argued that we have reached what is known as peak oil — when the maximum number of barrels of oil are being produced per year, and thereafter every year fewer barrels of recoverable oil will be available to suck up from under the surface of the earth. When that happens, he said, the carbon economy doesn’t just begin to recede. It collapses, with the breakdown of the First World’s transportation systems, the collapse of industrial economies, and the attendant resource wars that are inevitable when an essential resource is no longer as abundant as human demand.

But then came great technological breakthroughs in fracturing (fracking) around 2005. Now we appear to be awash in essentially infinite carbon by way of previously unrecoverable oil and natural gas. This is good news for the carbon-addicted industrial economy, bad news for the planet. Just at the time the world (and especially the United States) started to get serious about making the hard transformation to a post-carbon economy, the carbon floodgates opened, and we were permitted to slip back into complacency again.

These conversations (internal and external) I will carry on for the next few years in my journeys in search of America as it approaches its 250th birthday. I believe it is essential that I travel with a high sense of purpose, take advantage of this opportunity to listen to America at this critical juncture of our national experiment, and never forget the immense privilege of getting to do what I am so thrilled to be about to do.

I’m counting the days until I get to fetch my Airstream out of winter storage and go out to sing the Whitmanesque Song of the Open Road. And I’m reading everything I can get my hands on.