Day One, Afternoon: Bismarck to Sioux Falls

Leaving the Whitestone Hill battle site, Clay continues south to Sioux Falls in the afternoon, stopping at the one-time homestead of American author Hamlin Garland.

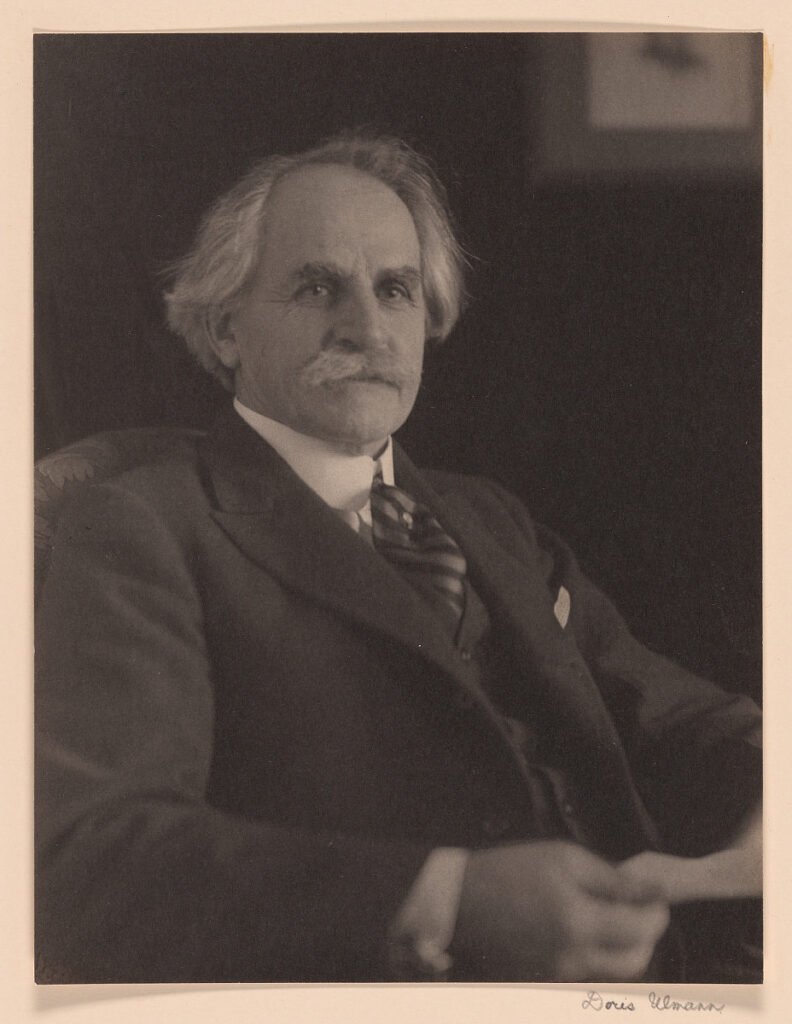

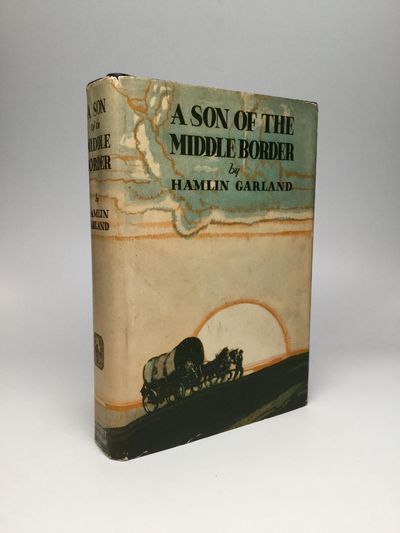

As I continued my drive that day and not far into South Dakota, I visited the one-time homestead of the author Hamlin Garland. Hamlin Garland (1860-1940) wrote Main-Travelled Roads, A Son of the Middle Border, Rose of Dutcher’s Coolly, and much more. Garland received the Pulitzer Prize in for biography in 1922. He grew up partly north of Aberdeen, South Dakota. In my view, A Son of the Middle Border is tied for best autobiography of someone from the Great Plains with Eric Sevareid’s Not So Wild a Dream. They are different but somehow linked. Sevareid, who became an iconic CBS news correspondent, was a gentle Nordic prophet. He grew up partly in North Dakota (Velva), left, and rarely ever returned, but he never got that small-town Midwestern friendliness out of his system. At the end of Not So Wild a Dream, which closes with the detonation of nuclear devices at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Sevareid says maybe the world would be a better place if it were more like Velva, North Dakota. Even now, it is a surprising end and a tremendous endorsement of small-town life.

I diverted from my route to make the Garland pilgrimage. I had looked up the address a day earlier, so I got within a couple of miles before I started to slow down and keep my eye out. Keep your eye out for the sign! I was told. And there it was, a giant glacial boulder the size of an old VW sitting on a neatly manicured farmer’s front yard. And on it was a bronze plaque explaining that Garland lived here: “Hamlin Garland, who rose to distinction in American letters, resided on this spot 1881-1884. Here stood the Garland homestead where he began his first book, Main Travelled Roads.”

Main-Travelled Roads (1891) is a compassionate tribute to how homestead women toiled, suffered, and endured loneliness out on the prairies of America. It’s a collection of stories set in a place like northeastern South Dakota. And the subject is farm women. Garland was not nearly as dark as O.E. Rolvaag, whose Giants in the Earth (1927) is easily the greatest classic of Great Plains literature, and that includes Willa Cather’s My Antonia! But things in A Son of the Middle Border break my heart with lovely nostalgia every time I read it. Garland wrote:

“Whenever the pressure of our complex city life thins my blood and numbs my brain, I seek relief in the trail; and when I hear the coyote wailing to the yellow dawn, my cares fall from me – I am happy.”

I got out to take photographs. Then I saw someone inching along in an ancient yellow tractor. I walked up to say hello. The driver shut off the tractor and leaned down a little for our talk. He said he has only owned the farm for a couple of years, and the man who was responsible for erecting and maintaining the sign (from Fargo, he thought) was insistent that as the new owner, he must take special care of the sign and be comfortable with hordes of literary tourists who will be driving through. The new owner was glad to do so. And the plaque looked perfect, beautifully plated! I asked him if he had ever had the chance to read any of Garland’s books. No, but he’d read some articles about him. He was still settling in at the ranch and had not yet had time to learn much about Garland. Next time I’m there, I will bring him a copy of Main-Travelled Roads.

I’ve done some Hamlin Garland proselytizing in my life and urged at least a hundred people to read A Son of the Middle Border. But so far, nobody has ever told me they read the book. A few started. But I’m not giving up. The book is beautiful and carefully modulated between seeing the homesteads of the plains as a new Eden or the fourth level of Dante’s Inferno. I asked my host if there were any Hamlin Garland festivals nearby. They did something at the college in Aberdeen a while back but other than that, no. Just a few cars per year, maybe even a dozen, stop. “I don’t see them all of course, when I’m in town or over to the shop.”

Later that evening, I checked into a conference hotel in Sioux Falls. It’s the same conference hotel you see in 300 American cities: the open atrium, glass elevator, and long alleyway to the Convention Center, where you may present your talk in Room A or C or the Wilson Room and the Roosevelt Room. I rode down the glass elevator four or five times that evening. Each time, a big group at a big table in the lobby bar pointed up at me, and each time — given the number of rounds they consumed — more boisterous. They did not know me, and I did not know them, but they regarded a man in a glass elevator as fair game.

In June, Clay drove from his home in Bismarck, North Dakota to Vail, Colorado. A focus of Clay’s two-week road trip was exploring little-remembered sites of tragic encounters between Native Americans and an expanding, westward-moving white population of the 1860-1880s. Clay’s stops included a battle site at Whitestone Hill in North Dakota in 1863, as well as the spot in Nebraska where Crazy Horse was killed in 1877, and Colorado sites commemorating the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864. Along the way, Clay also visited the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site, the U.S. National Grasslands, and a forgotten mountainside in western Colorado, where the federal government detonated a nuclear bomb in 1969 in an experiment to explore the peaceful use of atomic weapons. And — as in all good journeys — unexpected and unrelated roadside distractions provided plenty of ways to think about America.