Day Two: I-94 Sioux Falls to Wall, South Dakota

Clay visits the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site and learns how an extraordinary but unsung group of U.S. Air Force missileers operated on the front lines of America’s nuclear defense during the Cold War. This is day two in Clay’s road trip from Bismarck to Vail, Colorado.

I drove from Sioux Falls to the outside of Wall, South Dakota, at sunrise.

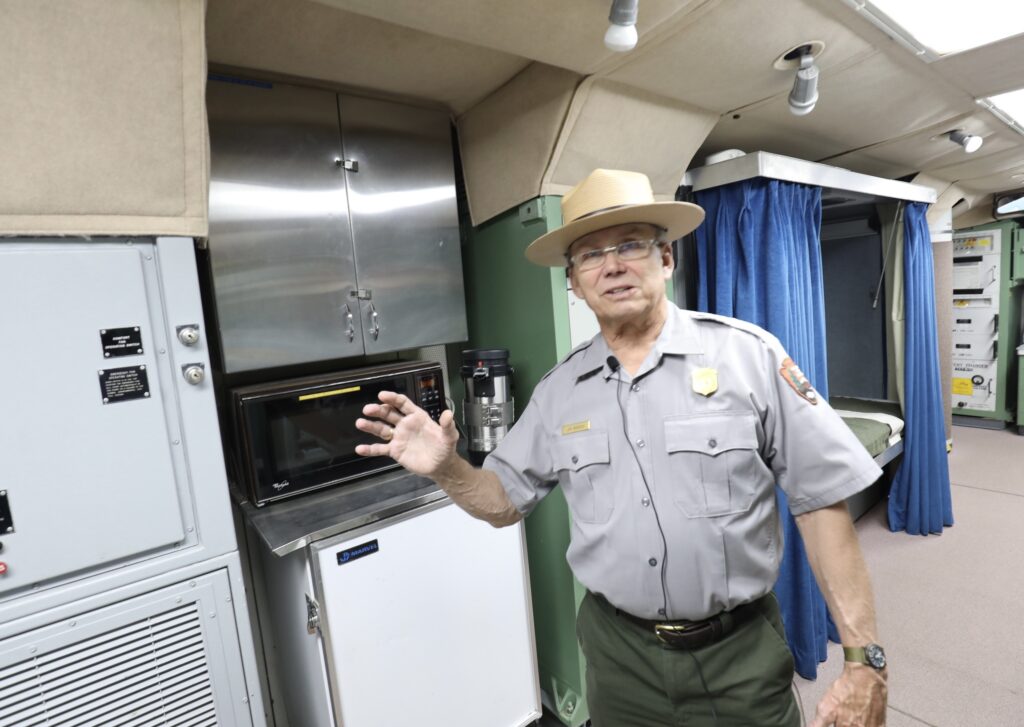

I spent the day with three extraordinary men there to discuss the history of intercontinental ballistic missiles during the Cold War. Jim Boensch, my principal host, formerly a missileer, now an interpretive ranger; Tim Pavek, the “father” of the National Historic Site; and Al Hall, a former member of the maintenance crew at the S.D. missile wing.

Jim Boensch gave me a detailed tour of the whole complex, above and below ground. The site restricts the number of people who can tour the underground missile site because the elevator only holds six people at a time. I’ve visited a similar missile complex at Cooperstown, North Dakota a few times, and a dear friend and a long-ago missileer gave me his amazing tour. But it was good to be there with Jim Boensch, who was doubly knowledgeable. Jim spent a career in the U.S. Air Force’s atomic branch and has served as an interpreter at the Wall site longer than he can remember. Jim has a great sense of humor.

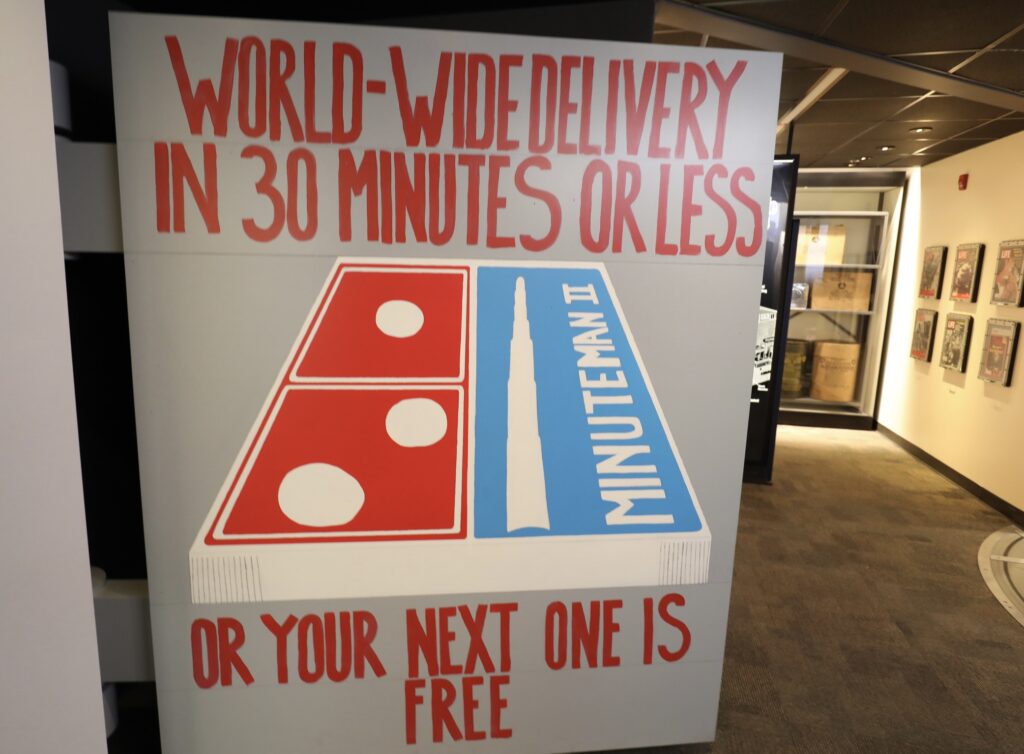

There are dentist jokes (“Gee Doc, you’re looking down in the mouth”) and banker jokes (“Bankers do it with interest,”) and plumber jokes (“For thirty years I told my work partner to get the lead out and all that time he thought I was talking about pipes.”) So, of course, there are nuclear missile jokes. Some of Jim’s shtick is so polished that it has taken years to perfect, but I laughed out loud every time and instantly liked Jim and his colleagues. Their favorite joke (also painted in the bunker) is the top of a Domino’s Pizza box saying “World-Wide Delivery in 30 Minutes or Less.” Pause. “Or Your Next One is Free.”

A Very Brief U.S. Ballistic Missile History

At one time, the U.S. maintained a thousand intercontinental ballistic missile sites. There were three warheads on many missiles, each with explosive power, making Hiroshima seem like a hand grenade. Today there are 400 ICBM missiles. The ICBMs are one arm of America’s nuclear triad: ICBMs, long-range bombers, and submarines. Each ICBM missile is in a hardened underground site. A massive cover on the missile silo is blown instantaneously off in the event of war. The missile in the silo contains solid fuel propellant, so it shoots like a bottle rocket, with no prep time needed, unlike the liquid fuel rockets we associate with NASA that rise slowly in the first couple of seconds. Every Launch Control Center (LCC) manages ten missiles spread out over the near landscape. Every five LCCs make up a missile squadron. Three squadrons make up a missile wing. Today my home state of North Dakota has 150 ICBMs operating out of the Minot Air Force Base. The Ellsworth AFB near Rapid City once had 150 ICBMs, too, but they were deactivated, erased from the landscape after the Berlin Wall came down. Thanks to the work of some determined individuals, one of the Ellsworth LCCs was saved from removal or destruction and one fortified missile silo. It was a long hard slog, but the Congress of the United States finally designated it as the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site in 1999.

The LCC (Launch Control Center) has facilities above and below ground. Above ground is the equivalent of a very low-budget Super 8 Motel. Several people worked every day in the above-ground facility. There were bedrooms, bathrooms, a commons, a TV room, offices, and a kitchen with a cook. But only two Air Force officers were down in the hole, a submarine-like capsule sitting on colossal shocks. Two Air Force officers were in that bunker at all times, from 1961 until deactivation and in the remaining missile wings in other states to this day. That’s how much we feared nuclear war: we had tens of thousands of men and women worldwide on alert, waiting for the call that never came. The protocols for the early era when the Ellsworth wing was established were more spartan than the next generation of bunkers. The one I toured had only one bunk. And the kind of steel toilet you’d associate with a jail cell — no essential privacy.

The two individuals were always of the same gender. This put women at a decided disadvantage because the first all-female crew would be two women who had never worked in the bunker before, no matter how proficient the training program. But they persevered.

The two missileers cannot start a nuclear war by themselves. They are passive in every way until the alert comes from the president of the United States. Then they must open separate lock boxes, each knowing only one combination. Then they must confirm receipt of their orders. They have no idea where the missiles are going. But suppose the process survives all the checks and hurdles designed to prevent a rogue missileer or an accidental nuclear war. In that case, each of the two needs to turn a separate key into one of two locks separated so far that no one person could ever turn both keys at the same time. Then the missile takes over, and the men in the hole have done their work.

After my tour, I had lunch with the staff at the historic site. Everyone had brought some part of the meal because it was the last day for their supervisor, who was moving on to another NPS facility in the southwest — baked potatoes with chili, chips and salsa, salads, and good desserts. When I tried to do the tour two years ago and stupidly showed up without a reservation, I envisioned the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site staff as haughty and all business. But of course, the team is a community and, out here in the big empty, almost family.

Then Jim gathered Tim and Al in the conference room. I turned on my miniature digital recorder and sat back to hear their stories. It was an utterly fascinating afternoon.

Making the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site a Reality

One of the things I have learned in my study of Theodore Roosevelt is that while he deserves nearly infinite credit for setting aside 230 million acres of America as permanent national park, national monument, national wildlife refuge, national game preserve, and national forest, it is also true that each of those conservation properties was the favorite cause of a person or persons who gave hundreds and even thousands of hours of their lives to doing all the incredible amount of work that happens before a president names a national monument or Congress creates a new national historic site. Most proposals for any of these designations fail to launch.

Tim Pavek is the man who made the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site happen. He is the first to interrupt to say that he is only one of many individuals who worked for this, and that it would not have occurred without … and no one person can ever achieve … all that. And he meant it. He was as humble about his achievement as it was possible to be. I got him to say just once in the interview, while he was trying to get to something else, “I guess you could say that I am the father of this place,” but it was said in an indisputable fact, not as a boast.

To make something like this national historic site happen, you must convince the town. You have to persuade the U.S. Air Force. You have to convince the U.S. Department of Transportation, the National Park Service. And you have to convince Congress. You have to find a member of the state’s congressional delegation willing to carry water for the project, probably over many years. You have to involve the governor. And then it almost gets done a couple of times and yet doesn’t, and at times it seems as if it just won’t ever get done. Tim Pavek is the man who kept the dream alive long enough to reach fruition. To launch.

And now it’s a permanent monument to a short but unbelievably tense period of human history. I find the Cold War more interesting than World War II (which is unendingly interesting). I was more or less born with the atomic bomb. Nearly every president since 1945 has alluded to or referred to nuclear nightmare and nuclear responsibility in his inaugural address.

What I loved most about these three men in the rural heart of South Dakota was their combination of modesty and deep pride. When I asked them why the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site is important, they each said, in a different way, that it honors the men and women who protected this country through the long Cold War at the missile triad of our nuclear strategy. They said the hotshot Air Force flyers get more respect and adulation than the guys down in the missile sites, which are not — to the untrained eye, at least — as sexy as submarines. In his excellent book Command and Control, Eric Schlosser writes, “In the hierarchy of Air Force officers, the fighter and bomber pilots each claimed to be at the top. Despite their intense rivalry, the pilots agreed on at least one thing: missileers occupied a rung far below them. Serving in an underground control center lacked the glamour of flying sorties into enemy territory or gaining command of the skies.” The men and women I met near the site just east of Wall, S.D., see the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site as a fitting tribute to the entire American missile community. Thousands of men and women, most of whom have long retired. Each at ground zero, waiting and wondering if there will ever come a signal to commence firing.

Al Hall was out there as a maintenance man on November 9, 1979, when NORAD sent an alert signaling that the United States was under attack.

Historian Eric Schlosser describes the moment:

Klaxons were sounded at SAC bases nationwide. Bomber crews ran to their planes, and missile crews were put on heightened alert. Fighter interceptors took off to look for signs of a Soviet attack. The National Emergency Airborne Command Post left Andrews Air Force Base — without President Carter on board. And air traffic controllers throughout the country prepared to clear America’s airspace for military flights, warning every commercial airliner that it might soon have to land.

It turns out it was a training tape accidentally loaded onto one of NORAD’s floor-length computers. Al and another man were at a missile doing some routine work. When they got the signal, they went straight into their training protocol. They were to drive a mile away from the site immediately but to keep sight of it and wait. This was to make sure that the evildoers were not hacking the system and poised to take possession the instant they fled. As they stood there contemplating the end of the world, Al said, “I’m supposed to get married next week.”

Al did get married a week later. And he loves to tell that story. I made the mistake of saying, “Well, there probably would never have been a wedding if that alert were true,” but he liked the story the way he told it.

According to Eric Schlosser, in his book Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons the Damascus Accident and the Illusion of Safety, in the investigation that followed, “twenty-three security officers assigned to the Combat Operations Center inside Cheyenne Mountain [Colorado Springs] were stripped of their security clearances … the security force responsible for protecting the nerve center of America’s command-and-control system was using LSD, marijuana, cocaine, and amphetamines.”

Jim Boensch told me many officers earned their masters while working in the hole. Plenty of free time, nowhere to go, no internet or TV or commercial radio. He said he did a lot of professional and personal reading during those years. He could remember what it was like to be down there when the Cold War really rattled America. A whiff of nostalgia. Probably he would not return to it, but it was a peak experience in his life, and nostalgia became a factor.

It’s worth doing some reading about this aspect of the Cold War. I recommend Schlosser’s Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons the Damascus Accident and the Illusion of Safety. He’s the guy who wrote Fast Food Nation. First, he turned me off the Big Mac, now NORAD’s invincibility!

I’ve written an entire chapter about North Dakota’s ICBM missiles in my last book, The Language of Cottonwoods: Essays on the Future of North Dakota. If you’re interested, I invite you to read my book.

In June, Clay drove from his home in Bismarck, North Dakota to Vail, Colorado. A focus of Clay’s two-week road trip was exploring little-remembered sites of tragic encounters between Native Americans and an expanding, westward-moving white population of the 1860-1880s. Clay’s stops included a battle site at Whitestone Hill in North Dakota in 1863, as well as the spot in Nebraska where Crazy Horse was killed in 1877, and Colorado sites commemorating the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864. Along the way, Clay also visited the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site, the U.S. National Grasslands, and a forgotten mountainside in western Colorado, where the federal government detonated a nuclear bomb in 1969 in an experiment to explore the peaceful use of atomic weapons. And — as in all good journeys — unexpected and unrelated roadside distractions provided plenty of ways to think about America.