On Sunday, March 3, 2024, a young humpback whale washed up on shore at the Oceanfront of Virginia Beach, Va. Even in death, it’s a magnificent-looking creature. These whale deaths happen, of course. That’s perfectly ok unless the poor creature was damaged when it collided with a ship or a propeller or stopped by garbage floating in the world’s oceans. We’ll find out.

I immediately wondered what would become of the Virginia Beach whale. I’m guessing it will be hauled away and disposed of (we probably don’t want to know the details). And the memory will fade. There will be an attempt to determine the cause of death.

This morning, I am thinking about Lewis and Clark. The beached whale reminds me of an incident during the winter of 1805-1806 at Fort Clatsop on the Pacific Ocean.

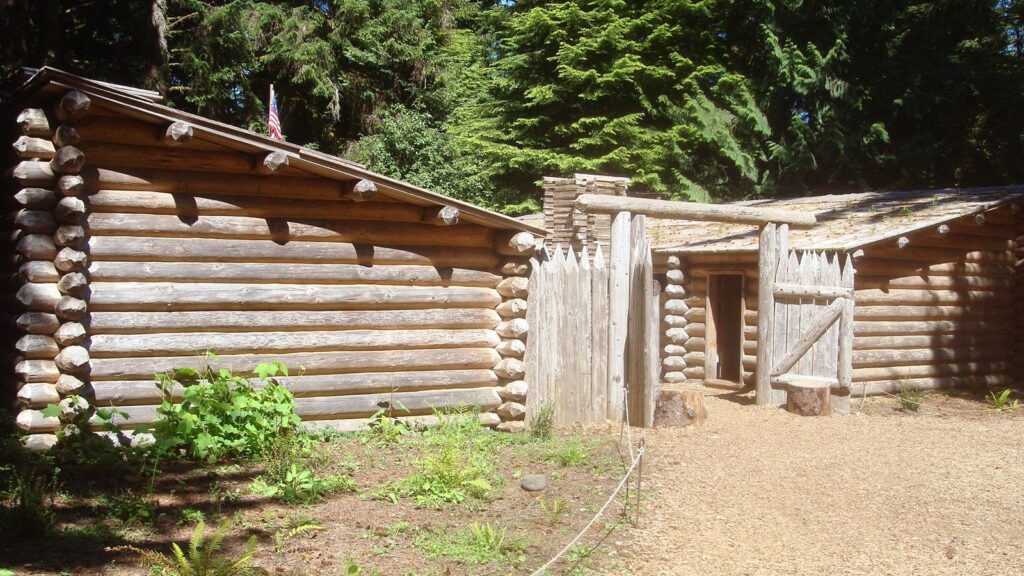

News arrived on December 29, 1805, that a whale had washed up on the beach a couple of dozen miles from their winter compound, Fort Clatsop, which was inland. The captains mounted a recon and recovery expedition led by William Clark.

Why?

Well, they were couped up and bored. An excursion must have sounded like a welcome break. And they were “hungry.” Not hungry hungry, but hungry for something with some fat on it, something that was not half-spoiled, something that wasn’t insipid. They had been eating lean and sometimes spoiled elk meat and a swamp potato called wapato root for many weeks. And they were curious. I wonder if any of the expedition’s men, except possibly for John Ordway, had ever seen a whale before.

Then came an incident.

Just as the recon group was about to set off for the coast, the Shoshone-Hidatsa Native woman Sacagawea stepped forward to register a protest. Think about this for a moment. Imagine these Euro-American army officers (with the view of the world and social hierarchies they carried) discovering that the “interpreter’s wife,” the “Indian woman,” was asserting herself. She made it clear to the captains that she wished to be part of the excursion. Given the awkward communications link — Hidatsa to Charbonneau, French to Francois Labiche, English to Meriwether Lewis or William Clark — it’s unclear what the captains heard from Labiche, but they got the gist of it. Sacagawea said (said, said, said) that “she had traveled a long way with us to see the great waters, and that now that monstrous fish was also to be seen, she thought it very hard she could not be permitted to see either (she had never yet been to the Ocean).”

With evident amusement and condescension, Lewis and Clark complied. It’s a great moment in the Lewis and Clark world. What Clark reports is as close as we will ever get to a direct quotation by Sacagawea. But that’s not the moral of the story for today’s whale death at Virginia Beach.

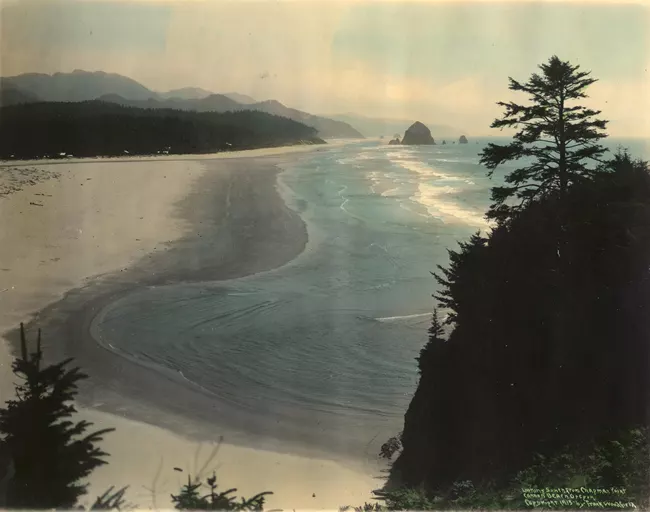

To get to the whale, Clark and his small group had to climb up over Tillamook Head, the high-rounded peak that juts into the Pacific Ocean. As the expedition whale party sat on top to catch their breath, Tillamook and Clatsop Natives came up over the hill carrying heavy flitches of a whale on their backs. During that rest, Sacagawea surely saw the broad expanse of the Pacific for the first time from one of the best viewing spots on the West Coast.

Clark reported that when they finally reached the site, at today’s Ecola State Park near Seaside, Oregon, “the Whale was already pillaged of every valuable part by the Kil a mox Inds. in the vicinity of whose village’s it lay on the Strand where the waves and tide had driven up & left it.”

There was nothing left. Nothing but some of the skeleton and other stuff that didn’t seem useful. The rest the local Natives had harvested with an efficiency that rose to the level of art. They had extracted everything of value to their economy and their comforts: blubber, of course, which they both ate and rendered into oil; bones for weapons and other implements; intestines and other bladders to store the whale oil once rendered; such skins as could be extracted from inner organs for use in wrapping or carrying loads: fat, muscle, bone, grizzle, tallow, oil.

Clark was surprised to see how quickly the Natives had processed the whale and hauled the processed bundles to their villages. Pillaged is a strong word. He had brought some trade trinkets (the expedition was nearly bankrupt), and he managed to buy about 300 lbs. of blubber with some hard persuading. That’s it. Clark was a little offended that the Clatsop leadership was not interested in trading, at least not for what the expedition offered. “The Kil a mox although they possessed large quantities of this blubber and oil were so prenurious that they disposed of it with great reluctiance and in Small quantities only.” His “utmost exertion” (with the help of his assistant sales managers) brought the expedition only a modest sampling of blubber.

“Prenurious” Natives. What if Clark had asked himself why the Natives were not eager to trade away this unexpected bonus to their diet and food security?

Well, at least Sacagawea got to spend some time at the ocean. Earlier, she had seen the Columbia estuary and several of the deep bays and, through the fog perhaps, an imprecise glimpse of the gray ocean far off in the distance. But now she could stand on the ocean shore, wade in, taste the salt, take in the unmistakable odor of where sea meets land. But, alas, she did not get to see the monster. The skeleton was intact enough that Clark measured it at 105 feet. She probably had a sense of the whale’s size.

Unfortunately, William Clark did not record her reactions to those hours on the Pacific shore or what she thought when she saw the whale’s remains. Her protest before the excursion was recorded, but her experience seeing those wonders of the Pacific Northwest goes unremarked. No one bothered to get her reaction.

There is an even more tantalizing sense of loss at work here. We got that one indirect quotation and nothing more. What if we could add her voice to the various narratives of the incredible journey? Imagine that it was somehow possible for Sacagawea to have kept her own journal! Imagine what it would say. We’d give anything for even a fragment, a scrap of her journal, and her account would now be privileged as a more “authentic” window on Lewis and Clark than what was written by those self-important exemplars of the Enlightenment. What would she say about the whale? What would she say about the ocean?

What would she say about moody and aloof Captain Lewis? Or about the black man who was Clark’s slave? Or about her dreams now that she had led them across the continent! Each of us, says La Rochefoucauld, is the hero of our own story. We’d want to know her true origin story. Was she born Shoshone, captured by the Hidatsa, and somehow married off to Charbonneau? Or was she born Hidatsa (or Crow) and captured by the Shoshone, after which she escaped and found her way back to North Dakota with the help of wolves? We’d want to know how she wound up with Charbonneau and just what she thought of him. We’d like to know what it was like to give birth at or near Fort Mandan with Captain Meriwether Lewis presiding as obstetrician. We’d want her to tell us what truly happened out there.

But no. Possibly, Sacagawea learned a few phrases in English during her time with Lewis and Clark. Still, she never had a true conversation with any of the white men, not even Clark, and certainly could not write in English or any other language. So we comb what few fragments exist out of the journals and hope we are giving them the right interpretation across so many barriers.

All that we really know about Sacagawea could be contained in a passport book. The rest is imagination, often fantasy.

But back to the moral of this whole story, inspired by events in the lower Chesapeake this weekend.

In 1806, the local Natives of the Pacific coast harvested, processed, and stored the entire whale in a very short period. They wasted nothing. This one thing is clear: there was something deeply admirable about that steady-state, green, sustainable, light-footprint people who understood something about the economy and interconnectedness of life that we have forgotten or perhaps never had.

We bring in a bulldozer and haul the whale carcass off for disposal — end of story.

And that’s ok, too. We could not live the way of the Clatsop, or the Mandan, Ojibwe, Cree, or the Lakota. We couldn’t then and certainly cannot anymore, not at 340 million and counting. The economy has to grow in sophistication to accommodate humanity’s numbers and inventiveness. It’s not all good, but we’re now so rich that we’re not going to rush out to harvest the critter on the shores of the Atlantic. Besides, news reports said it had been dead for some time and was starting to smell.

I’ve never stood next to a beached whale, but a few years ago, I stood on just about the same Oregon ground next to a huge dead seal. Kneeling down to touch its sides filled me with awe. Five hours later, birds had pecked out its eyes and were burrowing into the crevices in its flesh.

Everyone on the Lewis and Clark recon team must have been disappointed that they did not get there in time to see the whale before it was dismembered, not just Sacagawea.

As students of history, including indigenous history, we can only wish that an expedition journal keeper had been there when the monster was harvested to explain the whole operation from start to finish, including the protocols and implements with which the Natives did their work. It would have been a significant moment in coastal anthropology.

All we know is that they got it all, and they were “prenurious.”