I was saddened to learn of the death (November 7) of Frank Borman, the American astronaut who commanded the astonishing 1968 Apollo 8 mission to the moon. He was the oldest living astronaut. Apollo 8 (December 21-27, 1968) was in my opinion the greatest of the Apollo missions, even though it did not land on the moon. It was not intended to be what it was, a circumlunar flight, but in the summer of ’68 NASA’s Deputy Administrator George Low came up with the idea of doing something bold to the point of being reckless to get the moon program back on track (after the disastrous fire of Apollo 1 on January 27, 1967) and to make sure we landed on the moon within John F. Kennedy’s (“this decade”) timeline.

Apollo 8 “firsts” indicate the audaciousness of the mission. It was the first manned craft to leave earth orbit. It was the first human circumnavigation of the moon. It was the first human payload of the new Saturn V rocket, which had malfunctioned in some truly problematic ways in its unmanned tests. It was the first time humans looked back on the Earth from another celestial orb.

At the time of the mission, the moon lander, the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM), was not yet ready, so instead of waiting to test it in Earth orbit, Apollo 8 traveled without one and went to the moon ahead of the careful sequencing NASA had long since worked out. If Apollo 8 had failed catastrophically, it probably would have been the end of the Apollo program. NASA was taking a calculated risk and Frank Borman was precisely the man to command the mission.

Borman’s life trajectory comes straight out of Astronaut 101. Born in Gary, Indiana, but grew up in Tucson, Arizon. Grew up in some poverty. Fascinated with air flight from the age of five, received his pilot’s license by 15 at considerable financial strain. West Point after the war. Massachusetts Cal Tech. Joined the Air Force. Was not sent to Korea. Married his high school sweetheart Susan Bugbee, a strong and determined woman who made it clear she was not going to wait around forever. A stint as a test pilot at Edwards Air Force Base in California (the domain of Chuck Yeager). Second class of NASA recruits. Flew Gemini 7 in 1965 for 14 days, setting the record for longest space flight (until 1970). Gemini 7 also achieved the first space rendezvous, the essential requirement for a moon landing mission.

Borman’s wife Susan was an amazing woman. She definitely had the right stuff. When Frank drove home to tell her of the audacious mission in the fall of 1968, she immediately said, “OK!” but she soon went to see flight director Christopher Kraft, whom she trusted to tell the truth. “Chris, I’d really appreciate it if you’d level with me,” she said, “I really want to know what you think their chances are of coming home.” When he realized that she wanted the unvarnished truth, Kraft replied, “How’s fifty fifty?” On Christmas Eve 1968, before the critical thruster burn required to propel them out of moon orbit and back to Earth, she sat down and wrote out a plan for Frank’s funeral service (and his eulogy) if he did not return. She declared that the moon would be — if necessary — a magnificent place to die, serving one’s country, exploring the cosmos. People should joyfully imagine Frank orbiting the moon forever. “That’s what he would want,” she reckoned. They had two sons together. They spent their lives together. She died in 2021.

Frank Borman was by all accounts a stern, no-nonsense commander. One of my favorite historians Andrew Chaikin has written, “When Frank Borman walked into a room, you knew that he was in charge.” His motto? Duty, Honor, Country. He did not allow his fellow crew mates to relax on the great journey, even when there was nothing much to do.

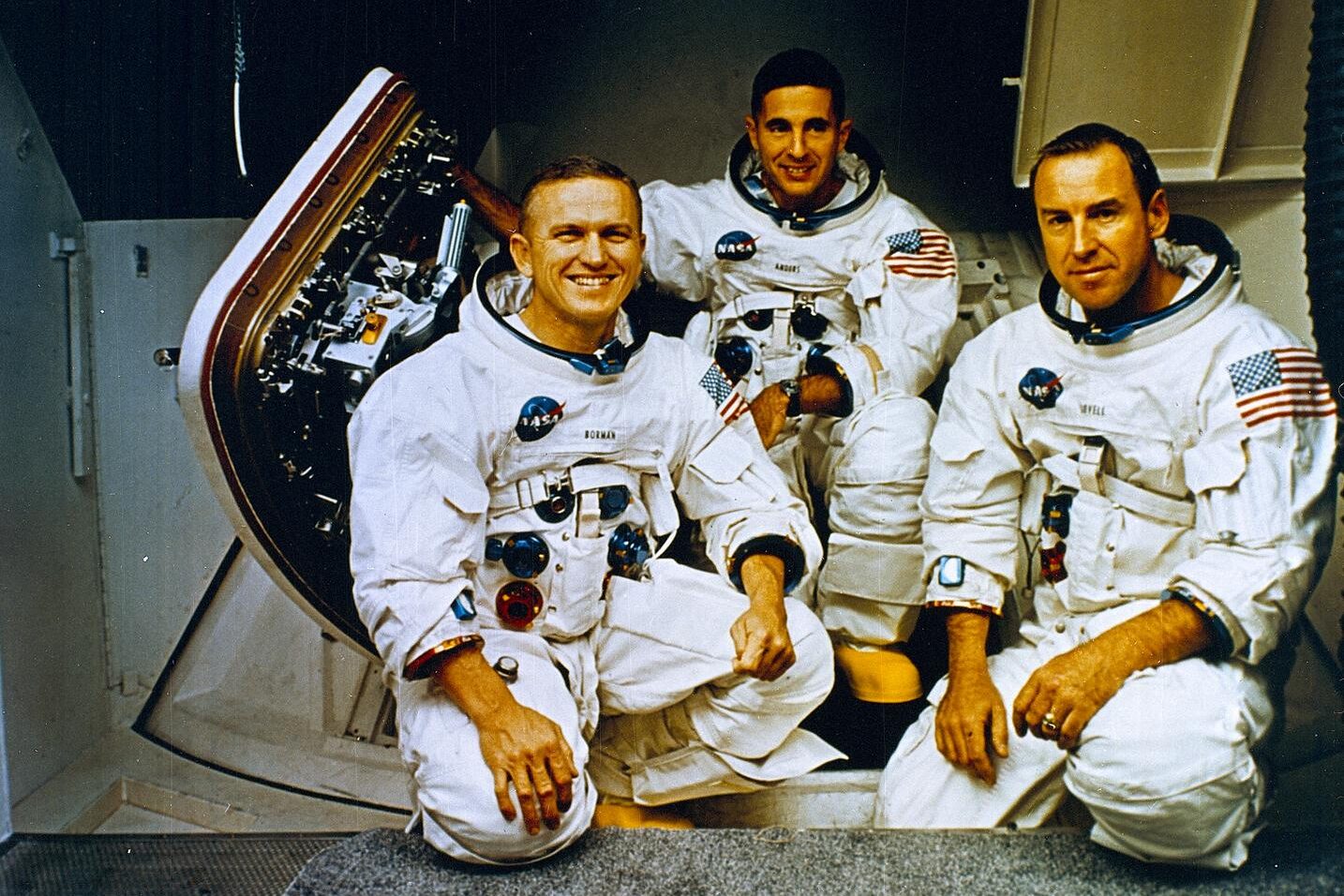

His Apollo 8 crew mates were William Anders and James Lovell. Lovell’s chief fame was yet to come. He would be the command pilot of Apollo 13, the moon mission that suffered a catastrophic explosion just 56 hours into the flight and yet somehow flipped around the moon and came all the way back to Earth safely. It’s the basis of one of the best space movies ever made, Apollo 13, starring Tom Hanks and Kevin Bacon. Lovell’s coolness and grace under fire, his devotion to his family, especially his aging and fretful mother, made him a national hero.

Earthrise

William Anders is immortal for another reason. He took the famous Earthrise photograph on December 24, 1968. Few photographs change the way people think. This one did. Anders was the mission’s designated photographer (Hasseblads!) and he frequently earned rebukes from all-business Borman for gazing out the window and taking photographs when Borman wanted him to be more concerned about the things that would keep them safe and get them home. But when the crew saw the Earth rise above the horizon of the pale, cold, lifeless moon, Borman lost his characteristic reserve, gushed “Oh, my God! Look at that picture over there! Here’s the Earth coming up. Wow, is that pretty!” Borman was the first to see it and he was soon barking out suggestions about the best way to capture the moment on film. When they figured that out, Borman ordered, “I got it right here! … Take several of them!”

Remember, the film would have to be developed back on Earth. Today you would get instant results. We all know that photos of sublime places seldom do justice to what the observer saw in real time. When he took the photographs, Anders could have no idea how the finished print would look. He knew what he saw, but he did not then know that it would become one of the most important photographs in human history.

Earthrise was a game changer. As Apollo 8 historian Jeffrey Kluger put it:

Over time, Bill Anders’s Earthrise photo became the defining image he’d sensed it might be, reproduced hundreds of millions of times on postage stamps, wall posters, T-shirts, coffee mugs, and more. Both Time and Life magazines ranked it among the hundred most influential photographs in history, and the image would widely be credited with animating the environmental movement, which was just beginning to gather momentum in 1968 and became a global force within the year.

Earthrise is the prime document in the Overview Effect — the idea that once you see the Earth in its entirety from space, you can never think about life on Earth in the same way again, that there is a mystic graduation to a higher order of consciousness. I don’t know if that’s invariable, but I would be glad to find out. Unfortunately, NASA has not been returning my calls!

The Genesis Gesture

But it is what happened later on Christmas Eve that gave Apollo 8 immortality, even spiritual immortality. Although NASA and the Apollo program were a triumph of hard mathematics, engineering, and Newtonian mechanics, a seemingly pure effusion of the scientific paradigm and the post-magical mind, a surprising amount of spiritual and religious activity occurred on America’s space missions. (Surely something similar was true from Russian cosmonauts no matter how much materialist-atheist indoctrination they received from birth in the USSR) The best book on this subject is Kendrick Oliver’s To Touch the Face of God: The Sacred, the Profane, and the American Space Program, 1957-1975.

All three Apollo 8 crew members were committed Christians. Borman, for example, recorded a prayer in lunar orbit to be played in his home church during the Christmas Eve service. It was his turn to do one of the readings, and he was going to be absent! Next best thing: prayer from the moon!

Once the mission was planned to take advantage of the best window of access, everyone realized that the crew would be circling the moon on Christmas Eve. That demanded some kind of observance. Well before the launch on December 21, NASA’s assistant administrator for public affairs Julian Scheer merely instructed Borman to “say something appropriate” during the broadcast scheduled for Christmas Eve. “He offered no further guidance,” writes historian Kendrick Oliver. During a crew discussion Anders suggested they read the Christmas Story. To his great credit, Borman thought that was too exclusionary; the message should have something like universal application to people of all nations and religions.

Uncertain of what to do, Borman contacted Simon Bourgin of the U.S. Information Agency. Bourgin had escorted Borman on his world tour following Apollo 7. Equally uncertain of what to do, Bourgin outsourced the problem. He contacted his friend Joe Laitin, a well-traveled and terrific journalist who served as a communications official for the Bureau of the Budget and had ties to the Kennedy Administration.

Laitin agonized over the assignment. After days of uncertainty and many drafts, with the deadline approaching, it was Laitin’s wife Christine who conceived the Genesis moment. As Laitin labored in frustration through one night trying to formulate something that was appropriate but not pretentious or divisive, Christine padded down the stairs at 4 a.m. How about the opening of the Book of Genesis, she asked. The first 10 verses of Genesis would have universal resonance even for people worldwide who were neither Christians nor Jews nor Muslims. All cultures develop origin stories, and most of them have to account for the beginning of the universe. This was a perfect, ecumenical choice that transcended its Judeo-Christian source.

Borman’s two fellow crew members liked the idea and when Borman ran the proposal up the chain all the way to the top of NASA, everyone approved.

Think of the dynamic convergence: Christmas … the moon just outside the window necessitating ruminations about the solar system … the Book of Genesis. At the end of a routine NASA capsule broadcast, with the usual zero gravity tricks and observations about the moon from close quarters, the three crew members left just enough time for their unannounced finale. Nobody outside of NASA had the slightest clue about what was about to happen. This was not a highly orchestrated moment. Borman didn’t even divvy up the verses to his comrades until half an hour before the broadcast. Anders would read the first four verses, Lovell the second four, and Borman would close with the final two.

For all of his seeming nonchalance, Borman understood what this moment would mean. He said to Anders and Lovell, “There will be more people listening to this than ever listened to any other single person in history.” A global audience at one of humankind’s greatest moments. The other greats — FDR on his fireside chats, JFK’s inaugural address, Churchill’s magnificent speeches in Parliament (conscripting the English language into the war, said one of his admiring critics), Martin Luther’s speech on the Mall — were heard by infinitely fewer people.

As the telecast wound down, with just enough time before the Command Module slipped around to the silent side of the moon, Anders said, “the crew of Apollo 8 has a message that we would like to send you.”

After a pause:

Anders:

In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, Let there be light: and there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.

Now Lovell:

And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day. And God said, Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters. And God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament: and it was so. And God called the firmament Heaven. And the evening and the morning were the second day.

Finally, Commander Borman:

And God said, Let the waters under the heaven be gathered together unto one place, and let the dry land appear: and it was so. And God called the dry land Earth; and the gathering together of the waters called the Seas: and God saw that it was good.

When Borman finished he said, perhaps to lighten the spiritual weight of the moment, “From the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a merry Christmas, and God bless all of you, all of you on the good earth.”

I remember watching the broadcast — I was a Space Program junkie — with my parents in our “den” in our home in western North Dakota, on a console color TV set, though the broadcast of course was in grainy, often ghostly black and white. My father and sister were outspoken atheists, my mother a nominal Christian, I, a confused but largely secular adolescent.

We were mesmerized (well, except for my sister). It was immediately one of the great moments in my life and it remains so six decades later when I have forgotten most of what I once knew about payloads and throw weights and fuel cells. We were filled with wonder and admiration, and there percolated beneath our family conversation a spiritual grandeur. Our eyes were moist and we felt shy together.

You could not hear those words without wondering, well, how did we get the heavens and the earth? How did the earth form? And what does the fact of (71%) water (apparently alone in the solar system) mean?

How did it all begin?

And it was Christmas, the time of the calendar year when the greatest number of people in America have contact with the Bible.

In his usual blunt way, Borman later insisted that his choice was not based on his religious faith. He needed something to say on Christmas Eve. This did the trick. “I didn’t give it any more thought than that,” he later said. I suppose we need to take him at his word.

Borman was offered a moon landing mission, but he declined. Looking back on his decision decades later, he said, “I would have not accepted the risk involved to go pick up rocks. I love my family more than anything in the world. I would have never subjected them to the dangers simply for me to be an explorer.”

Borman left NASA in 1970 and spent the rest of his career in the private sector, including an 11-year stint as the president of Eastern Airlines. Just before the millennium, he bought a ranch in the Bighorn Valley of Montana.

They are dying, the Gemini and Apollo astronauts. Of the 24 who have been to the moon only 12 walked on it. Eight of those men have died, just four are left: Buzz Aldrin (93), Charles Duke (88), David Scott (91), and Harrison Schmitt (88). Of the dozen who went to the moon but never landed, only two are still alive: James Lovell (93) and William Anders (90), both of Apollo 8.

The moment is coming, and soon, when every American lunar astronaut is dead. We can only hope that America gets another crew to the lunar surface before that happens.

Frank Borman may have been all business, but he embraced the Genesis reading the minute his friends suggested it. And later in life when he was asked about Earthrise, he said, “The contrast between our memories of the Earth and the color on the Earth and the totally bleak and dead moon was striking.” That moment, he said, he would “recall till the day I die.”That day was just two weeks ago. I hope his last thought was of December 24, 1968. After the crew landed, Borman received thousands of congratulatory telegrams. He only remembered one: “Thank you Apollo 8 you saved 1968.”